MQ 2024

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 33

Fall 2024Cartesian Anxiety

7.5” x 5.5” x 0.5”

About the contributors:

Alva Mooses is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. Her works across printed media, installation, and sculpture engage with earth-based materials to create an index of place and signal the memory of geological time. Alva holds a BFA from The Cooper Union and a MFA from Yale University. She has exhibited her work locally and internationally, most recently at Salón SIlicón in Mexico City.

Christy Spackman is a researcher whose work focuses on the sensory experiences of making, consuming, and disposing of food influence and are influenced by “technologies of taste.” She is a baker, aspiring candle stick maker, and fermenter of things.

Since the 1990s, supermarkets have used “Price Look Up” or “PLU” codes to streamline check-out and inventory. These codes help the supermarkets organize their produce with a four or five digit number which quickly tells the store the product’s size, growing method, type, and variety. All of these aspects ultimately help to determine the price of the food. Typically, all produce is labeled with a four digit number. For example, #4011 is the code for a conventionally grown yellow banana produced using pesticides. When the number 8 is added to the four digit code of fruits and vegetables, it indicates that the product has been genetically modified. If it begins with the number 9 then the product is organic. These codes are the same across all of the United States. (1) This labeling system does not apply at farmer’s markets where produce tends to be stickerless.

I only learned about these codes recently, but the system has added to my ongoing thoughts about trusting what I see. In the last Martha’s Quarterly, I introduced the issue by talking about fake artworks in museums and the prevalent use of AI to report information. Without PLU codes, apples look like apples, bananas are bananas, and oranges are oranges. Why would they be anything else? Of course, these fruits are technically what they appear to be, but how they are grown and produced influences the nutrition they give or do not give to our bodies.

Over the years, I have heard many things about GMOs and pesticides from the news, friends and family, social media, and many other anecdotal sources. I have been told not to worry, but on average I have been more encouraged to avoid products that have been genetically modified or have used pesticides. I wish this were not the case. I wish that when I see apples, bananas, and oranges, I could buy them with confidence that the fruit is completely nourishing- void of toxins or heavy metals. But because I have heard so much over the decades of my life, I cannot help but be wary of the systems put in place that are supposed to look out for the public’s well-being.

I don’t think I am alone in this apprehension. As I write this, the contentious US elections are less than a month away. People around me from both sides and in between the political spectrum are anxious about the results, all worried about the future for different reasons. The war in the Middle East seems to be escalating while people in America’s southeast are struggling to recover from the recent hurricanes. Beyond the PLU system, I cannot help but also grow anxious about multiple systems that I rely on and affect the lives of my family and communities.

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 33, Fall 2024 is called Cartesian Anxiety, a term that the philosopher Richard Berstein coined and used in 1983. The concept refers to our human need for a stable grounding in knowledge or facts, and when that foundation is disturbed, it leads to chaos and confusion. (2) For example, we trust that our institutions create laws and regulations that will protect us. But, when we are overexposed to contradictory information through anecdotal accounts, news reports, social media, and any other stream of information, our trust in these institutions can become weaker. Furthermore, conspiratorial thinking becomes more seductive because we naturally wish for and seek reasons for why the “ground” is starting to crack.

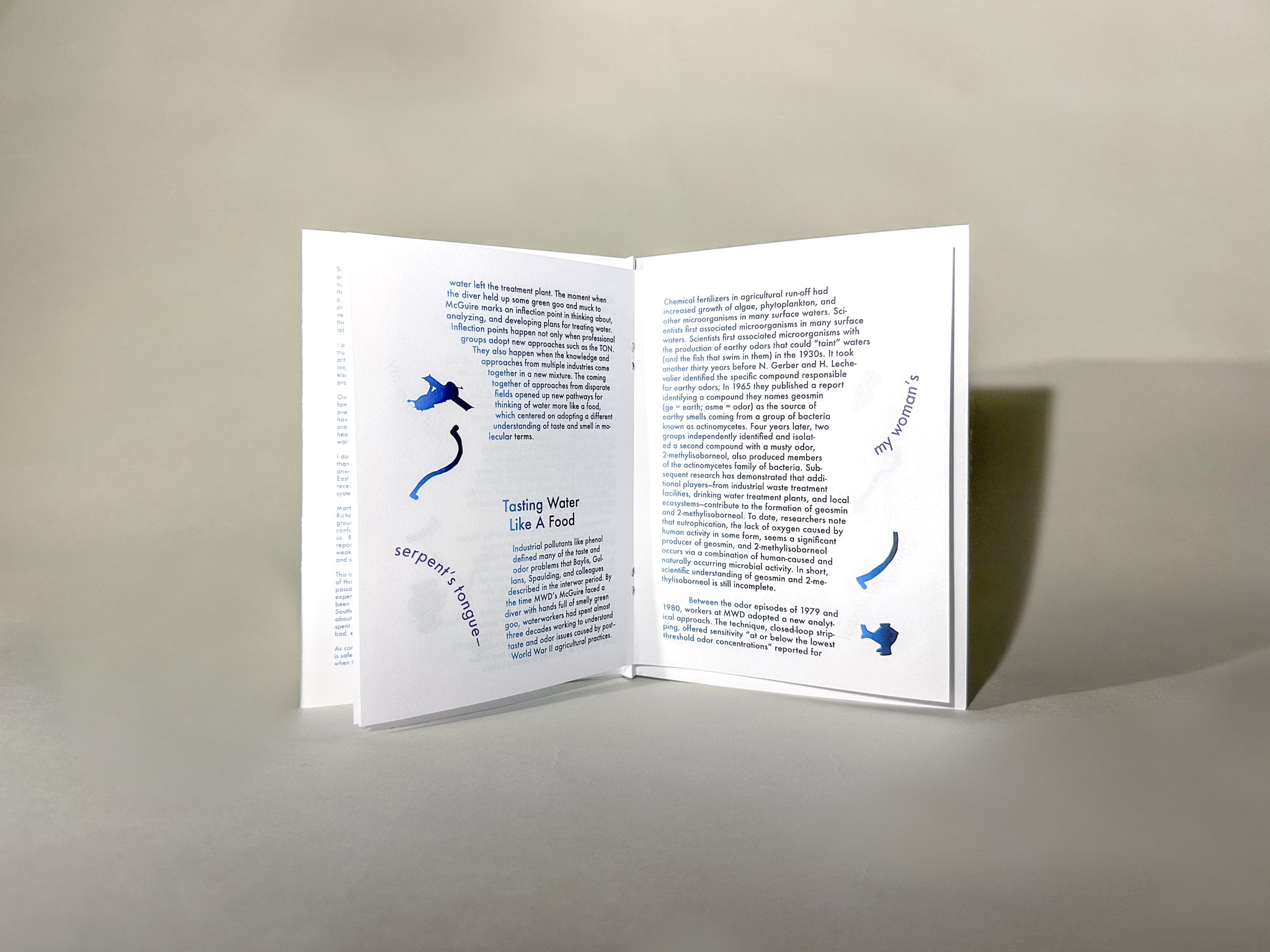

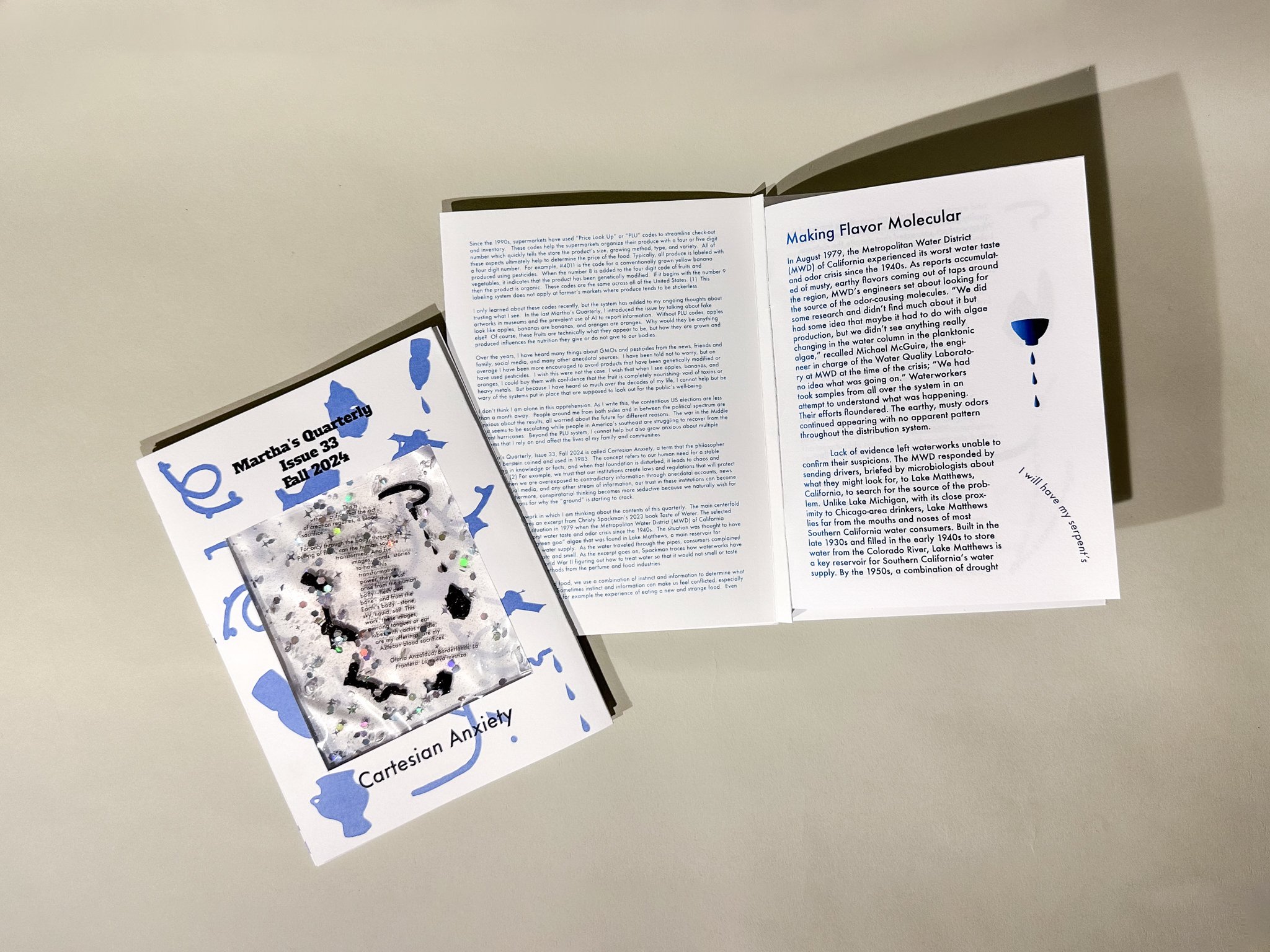

This is the framework in which I am thinking about the contents of this quarterly. The main centerfold of this zine features an excerpt from Christy Spackman’s 2023 book Taste of Water. (3) The selected passage tells of a situation in 1979 when the Metropolitan Water District (MWD) of California experienced the worst water taste and odor crisis since the 1940s. The situation was thought to have been caused by a “green goo” algae that was found in Lake Matthews, a main reservoir for Southern California’s water supply. As the water traveled through the pipes, consumers complained about an off-putting taste and smell. As the excerpt goes on, Spackman traces how waterworks have spent decades since World War II figuring out how to treat water so that it would not smell or taste bad, even borrowing methods from the perfume and food industries.

As consumers of water and food, we use a combination of instinct and information to determine what is safe or not to consume. Sometimes instinct and information can make us feel conflicted, especially when they don’t align. Take for example the experience of eating a new and strange food. Even though we are told it is safe to eat, the strange appearance or smell of a new food can easily make us hesitate to consume it. This tension between primal instinct and information delivered and superimposed by humans is embedded in the second component of this zine, which intervenes with the artist Alva Mooses’ recent body of work Medida del Mar (The Measure of Sea).

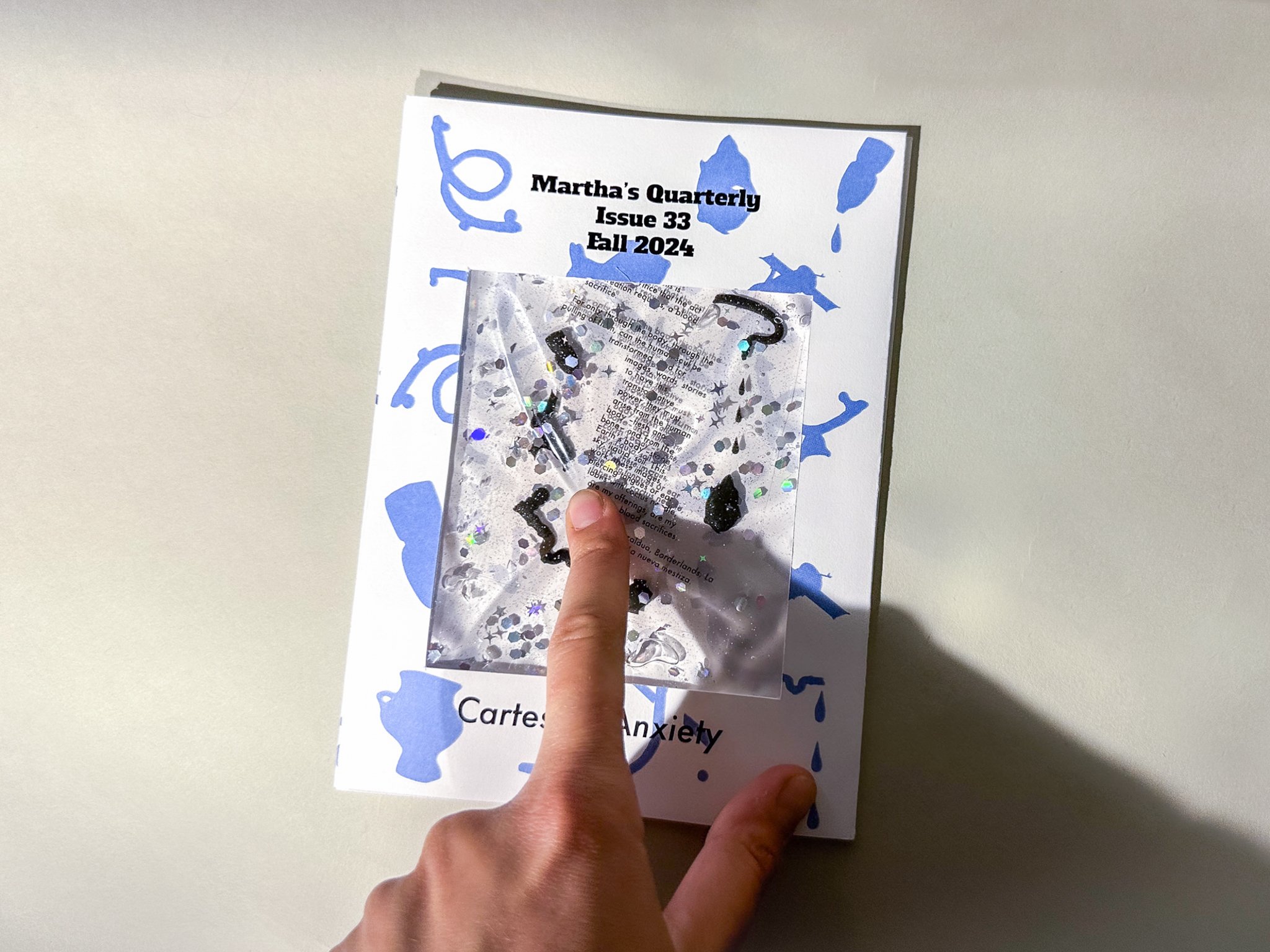

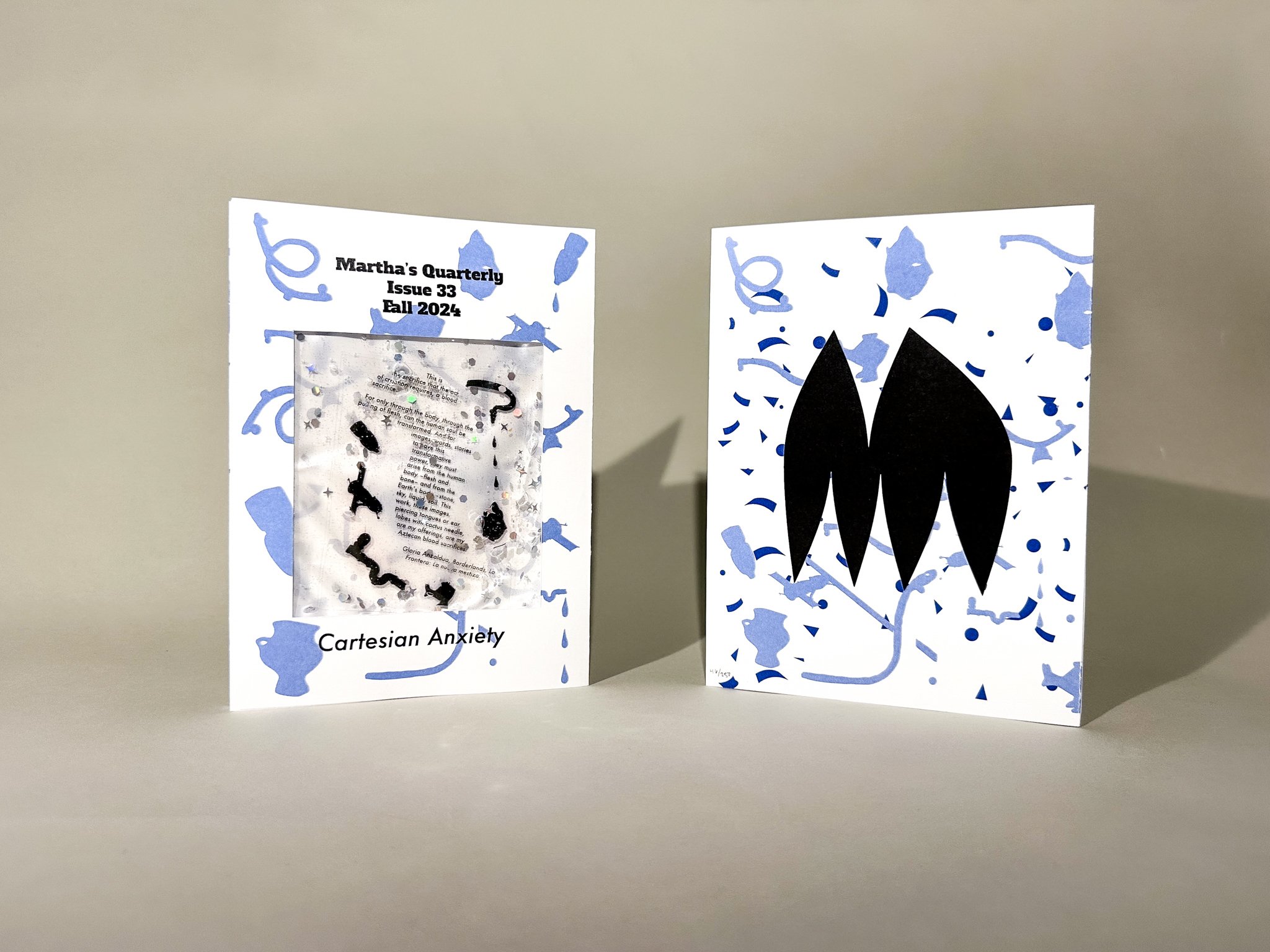

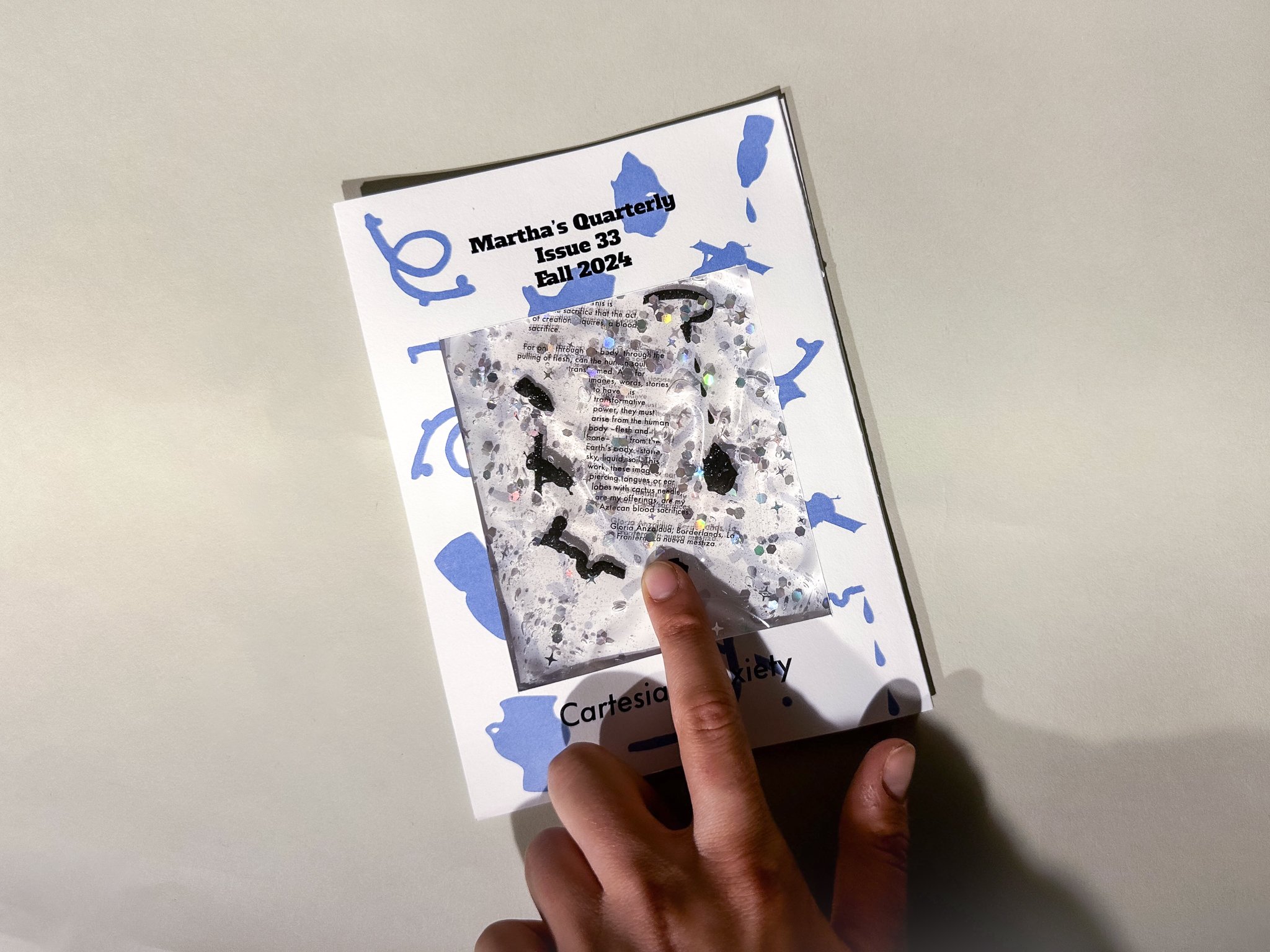

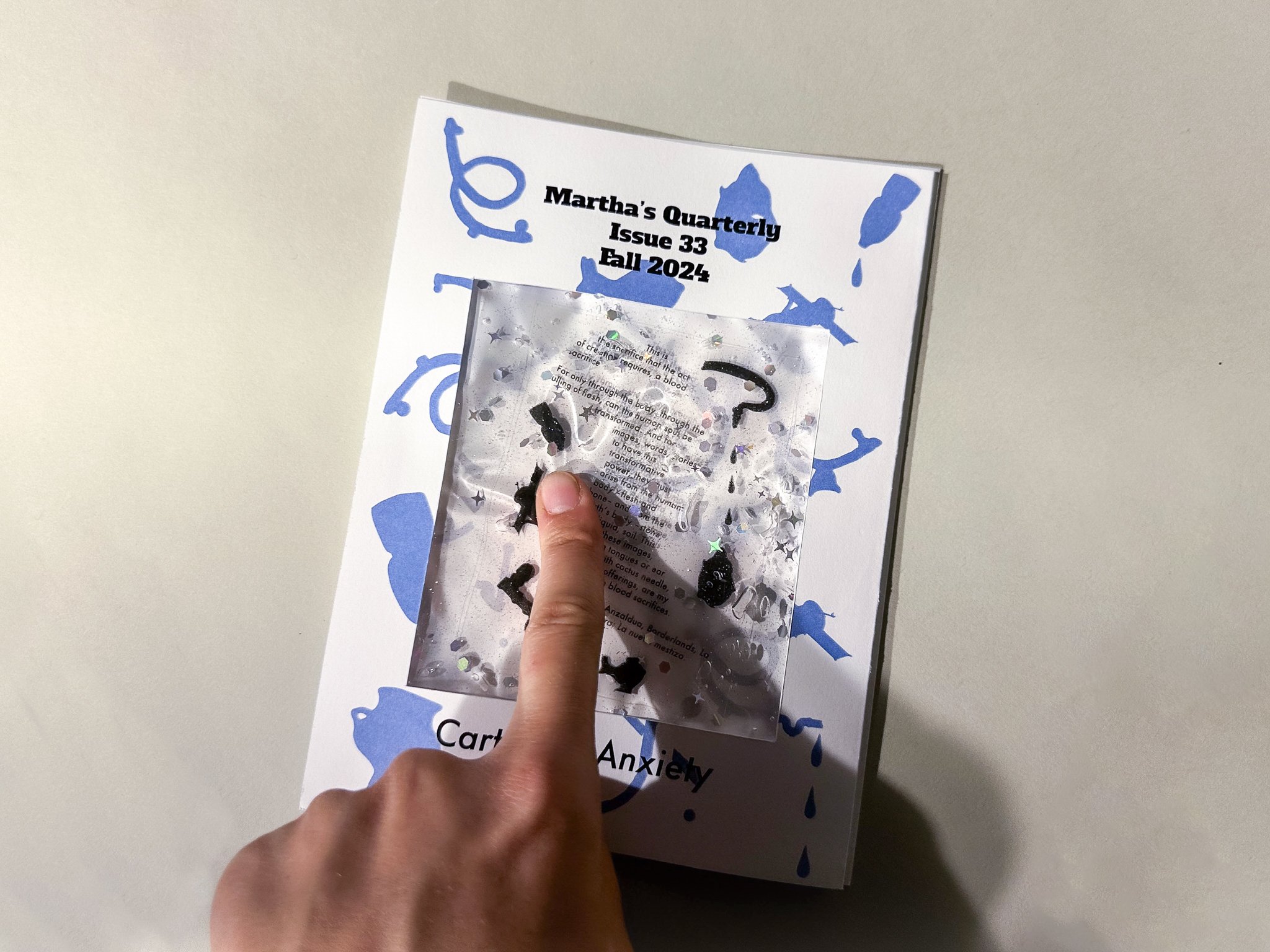

The shapes and icons that have been collaged all over and inserted in the cover’s sensory pack are extracted from the artwork Turtle Face and the Last Drop, where Mooses had pounded aluminum cutouts into symbols that point to ancient histories and human-made systems that strive to control societies. These images include milk jugs, water vessels, pipes, droplets, and a deconstructed globe. Floating in the sensory pack and slithering along the margins of Spackman’s writing are pieces of writing by Gloria Anzaldua, from whom Moose draws inspiration.

When you push through the clear goo of sparkling glitter and iconography, you’ll be able to read a short passage by Anzaldua. It is a vivid passage that alludes to motherhood and the intimate and bodily connection humans have with the planet. For me, this text along with Mooses’ work serves as a striking juxtaposition to Spackman’s writing. Together, they point to a tension that we constantly have to make peace with. This is the negotiation between gut instinct and information that strives to be objective and truthful while also being misleading and biased. Gut instinct is something that I see as intrinsic and deeply embedded in Mooses’ imagery– we all have it as a result of being children, parents, siblings, community members, and more. The sensory packet is presented on the cover of this zine to first direct you to something sensorial. It is your senses - your trust in water - that get pushed and pulled as the world of information swirls around you.

- Tammy Nguyen

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cartesian_anxiety

(3) Speckman, Christy, “Making Flavor Molecular,” The Taste of Water: Sensory Perception and the Making of an Industrialized Beverage, University of California, 2024, pg 67-93.

@passengerpigeonpress

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 33, Fall 2024, Cartesian Anxiety was produced using digital printing for all of its printed components. The inner pamphlet was printed on 20 lb. white and the cover was printed on 110 lb. cardstock. The sensory packet was made with vacuum sealed plastic, aloe vera gel, digitally printed acetate, and holographic glitter in varying shapes. The font used throughout was Fortuna in different sizes and styles. “Make Flavor Molecular” was used with permission from Christy Spackman and University of California Press. This issue was edited and designed by Tammy Nguyen and produced by Holly Greene, Chance Lockard, and Daniella Porras.

Published in October 2024, this is an edition of 250.

Martha's Quarterly

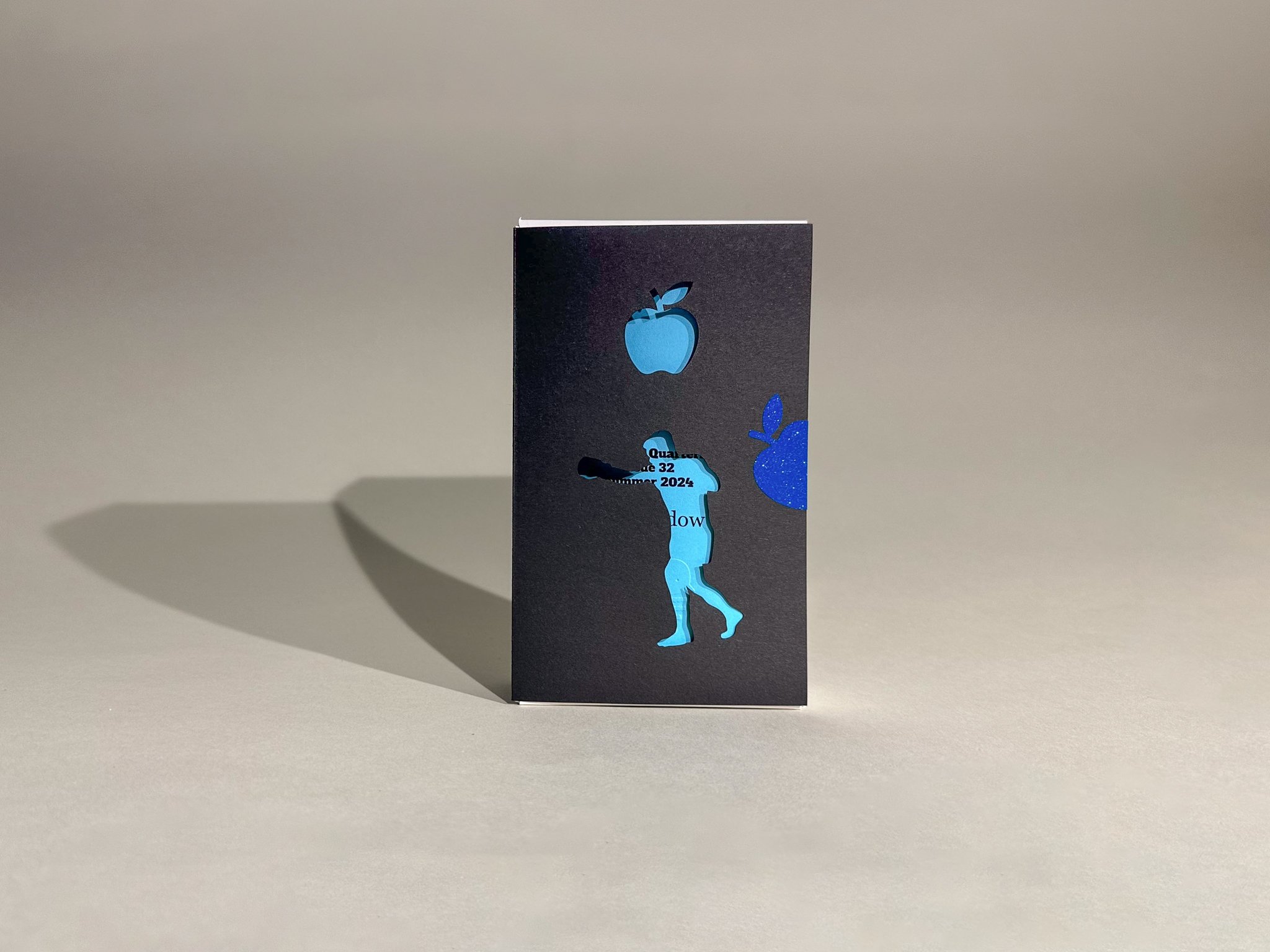

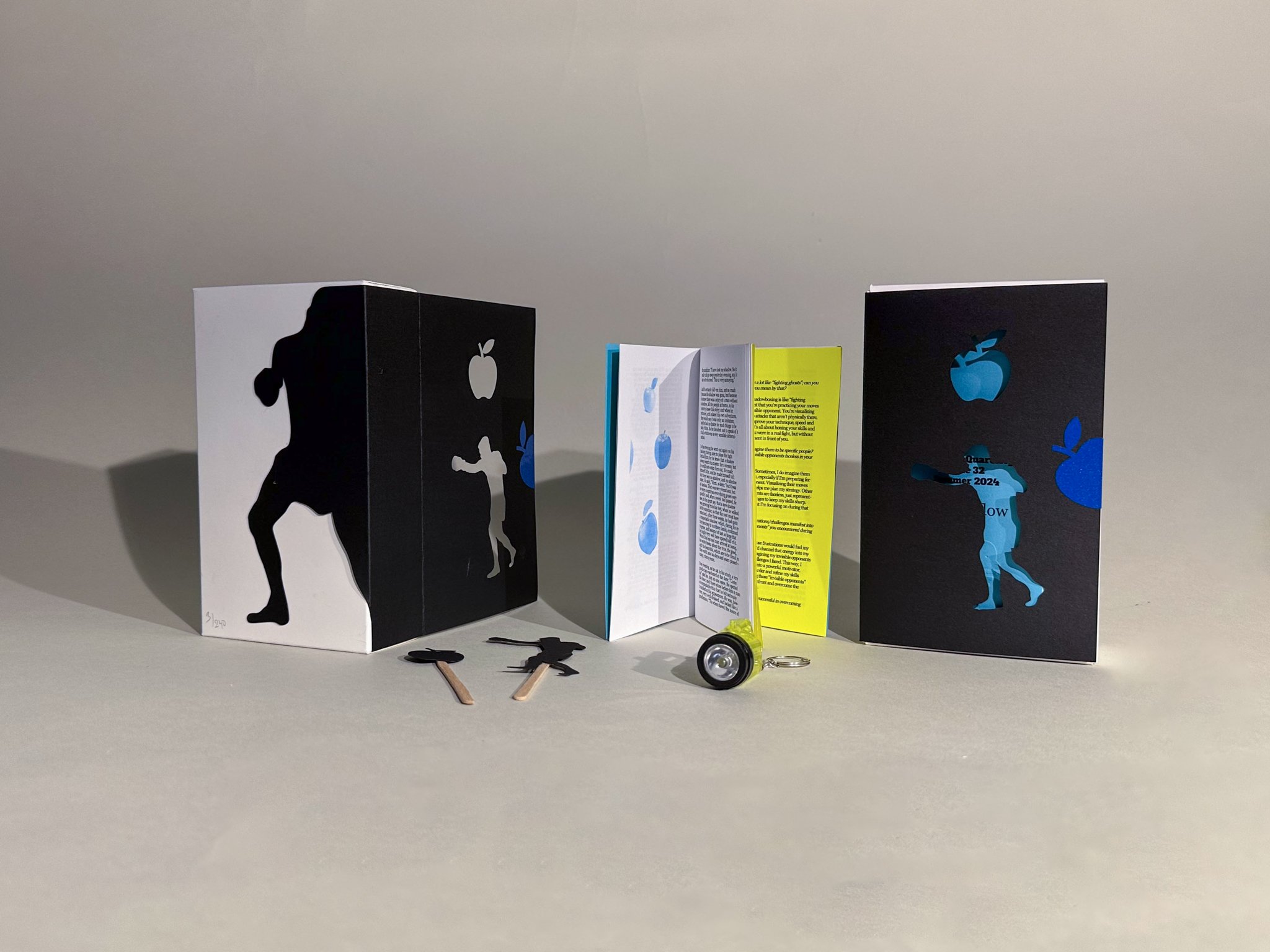

Issue 32

Summer 2024

The Shadow

6.75” x 4.25” x 1.5”

About the contributors:

Hunter Julo is a writer from Kansas City. They graduated from Wesleyan University in 2022 and live in Brooklyn where they dress the superheroes of tomorrow at Brooklyn’s Superhero Supply Co.

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) was a Danish author who wrote plays, travelogues, novels, and poems. His most loved and remembered works are his literary fairy tales, of which there are over 150 across nine volumes.

Sabine Chai is from Fairfield County, Connecticut. She is an undergraduate student at Vassar College pursuing a degree in Art History, and is hoping to enter the field of Art Conservation.

ChatGBT Muhammad Ali is an AI generated, digital persona of Muhammad Ali that was developed through the automated synthesis of online archives.

This summer, I have continued to ponder the importance or insignificance of truth. When I was living and working in Saigon fifteen years ago, I remember speaking to someone from the Ministry of Culture regarding artifacts at the Fine Arts Museum of Ho Chi Minh City. The authenticity of the objects in the museum was commonly questioned. It wouldn’t be strange to hear jokes about how the objects in the museum were all fake and that the real objects were probably sitting in some official’s house. I asked this officer whether or not she thought the object or its story was more important to the public. Without pause, she said that the story was more important, without the story, visitors would not learn about Vietnam.

I am awestruck by deepfakes. These are images and videos that have been entirely rendered, as in, they do not use source materials from real life, like a human subject or an environment. Rather, what you see has been built from synthetic elements generated by artificial intelligence. Some of this content has been so compelling that the message is undoubtedly absorbed— that is… if you don’t question the authenticity of the content in the first place. If I have to question, I can become disturbed, and at the very least a little bit distrustful.

This was my feeling when I saw Victoria Shi, the world’s first AI diplomat. Speaking on behalf of Ukraine’s foreign ministry, Victoria delivers statements from the humans working in the foreign ministry’s press service. The statements, she asserted, will be verified by real people. Victoria is a beautiful woman, modeled after Rosalie Nombre, a Ukrainian singer and former contestant in Ukraine’s version of The Bachelor. The foreign ministry said that Nombre took part in creating Victoria and that Nombre and Victoria are two different people. I am unsure if knowing any of this instills trust in the public. But, if Victoria continues to be seen, she will surely have her own life in the public’s consciousness. (1)

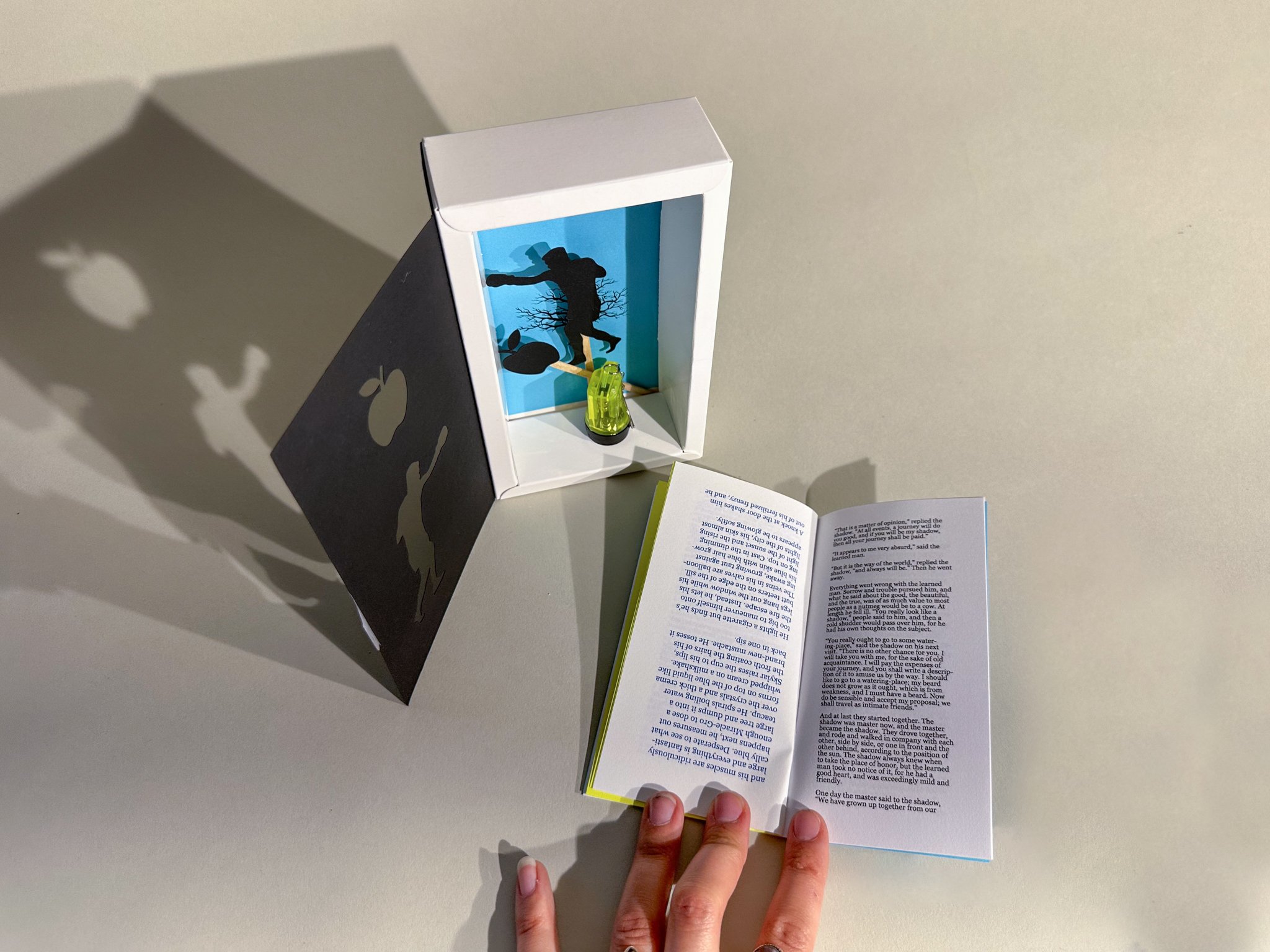

As I was thinking about this, I encountered a conversation between Salman Rushdie and Ezra Klein on the Ezra Klein show that inspired Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 32, Summer 2024, The Shadow. In April, Klein interviewed Rushdie on the debut of his new book Knife, a memoir and reflection on his life, relationships, and also his near-death experience when someone stabbed him fifteen times. At the beginning of the interview, Rushdie tells Klein of one of his favorite stories, The Shadow by Hans Christian Andersen, about a man and his shadow. The shadow leaves his man and lives a life of his own. It thrives to the point where the man in his old ailing age becomes the shadow’s shadow, and ultimately the shadow leads the man to his demise. (2)

Rushdie used this story as a way to speak about how his own life has been defined by a kind of shadow. Rushdie’s shadow was generated by the public after Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa ordering the execution of Rushdie due to the publication of his novel The Satanic Verses. As the conversation continued, Rushdie expressed frustration at how this fatwa affects how people perceive him. Every book he has published since the fatwa seemed to always refer back to the Satanic Verses and then the fatwa. He couldn’t control his expression— people’s idea of him seemed to take on a life of its own, thriving to the point that decades later a young man decided to seek him out at a literary festival to finish the fatwa’s ordering. (3)

Rushdie’s story really moved me, and I think it speaks to a conflict that many people share. How many times have we felt that the public or community took an idea of us and let it run free? How often have we felt the sadness that our true selves are not known to others?

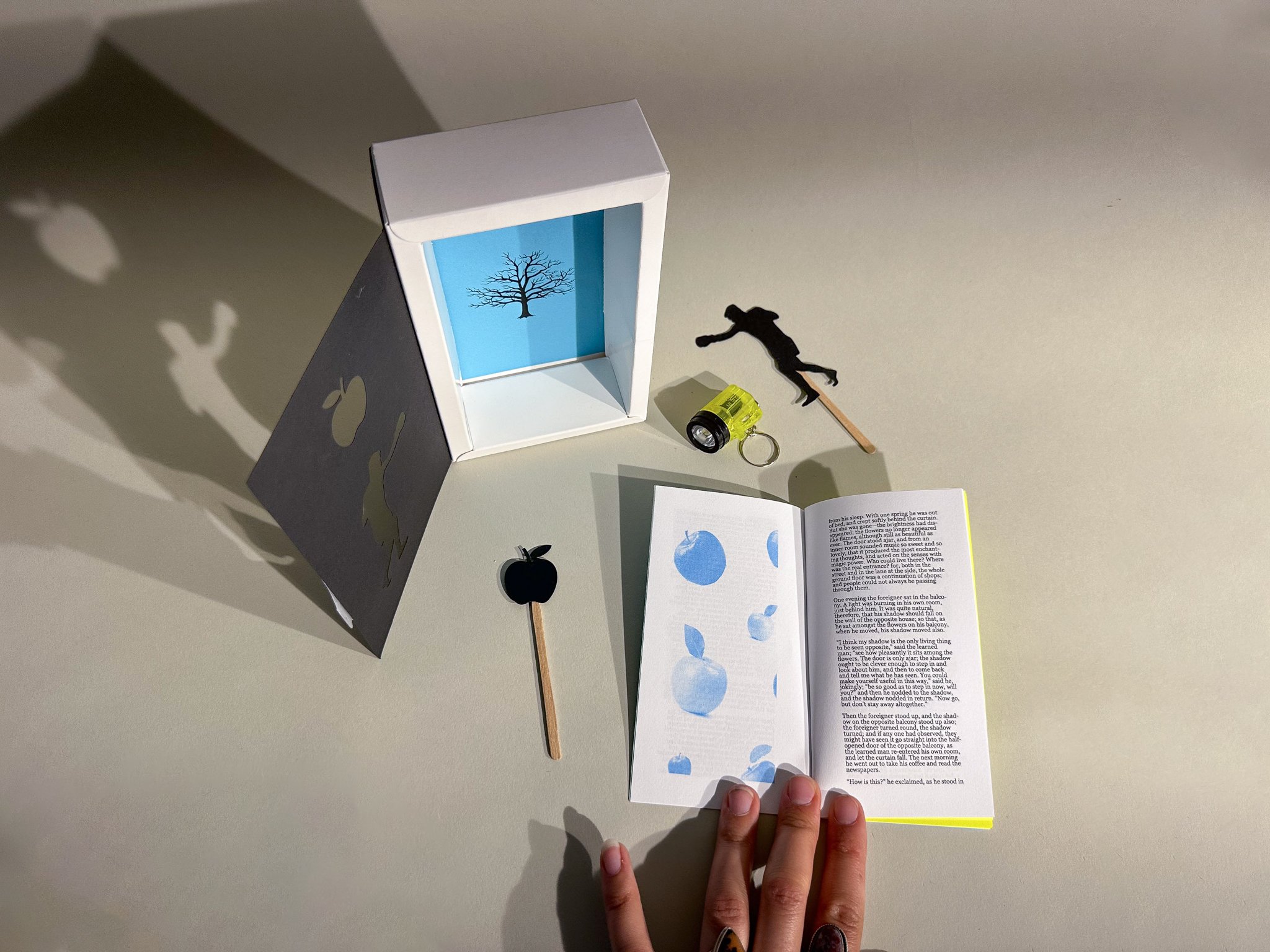

Hans Christian Andersen’s The Shadow is featured in this quarterly, and I asked the writer Hunter Julo to respond to it with their own fiction. The protagonist in their vignette is named Skylar, a young person who is exploring his gender identity as well as his overall identity in the world. Julo’s story takes us through Skylar’s thoughts where they remember an apple tree of his childhood. This later seems to represent a kind of shadow when a glowing blue apple is taken out of their throat by a girl named Greta. The blue apple seems to hold all of Skylar’s masculine aspirations and as it leaves his body, his previous biology reemerges.

Wedged inside of The Shadow and Julo’s fiction is a conversation between Sabine Chai and ChatGPT as Muhammad Ali, one of the world’s finest athletes who epitomizes masculinity. The conversation begins with Sabine asking Muhammad Ali about shadowboxing. He talked about why it was essential to his practice and how he would create invisible opponents through the training. Later on, he talked about the fame he achieved and suggested that it allowed him to become an activist for the civil rights movement, anti-war movements, and much more. Fame, it seemed, was part of his shadow which amplified his true self. But of course, this overly smooth conversation was generated by ChatGBT which takes all of its information from the internet. This AI can only ever be another shadow of the real Ali.

Enclosed inside of this box are a small light and two shadow puppets, one of an apple and the other of a boxer. Pasted into the bottom of the box is an image of a barren apple tree. Use the light to project shadows onto and around the tree. Use it to generate your own stories, which will also become more shadows of all of the truths and fictions shared here.

- Tammy Nguyen

(1) https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/may/03/ukraine-ai-foreign-ministry-spokesperson

(2) https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/26/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-salman-rushdie.html

@passengerpigeonpress

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 32, Summer 2024, The Shadow was produced using single-color photocopy, xerox, and cricut and laser cutting. Georgia font was used in various sizes and styles throughout. This edition was printed on text weight, Astrobright paper in varying colors. The work entitled The Shadow was sourced from Andersen’s website and has been released to the public domain. The short fiction by Hunter Julo was published with the author’s permission. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen with additional editing from Holly Greene. This quarterly was produced by Holly Greene, Sabine Chai, Cheney Hester, and Elisa Alt.

Andersen, Hans Christian. “The Shadow”. HCA.Gilead.org, http://hca.gilead.org.il/shadow.html.

Julo, Hunter. Untitled, 2024.

Published in June 2024, this is an edition of 240.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 31

Spring 2024

Wrinkle from the Sun

About the contributors:

Alexander Hill (1856 - 1929) was a medical doctor and professor at the University of Cambridge. He was a brain specialist who is credited as being the first person to use the term 'neuron' in English to describe the nerve cell and its processes.

Mely Kornfeld is a writer and recent graduate of Wesleyan University, where she majored in American Studies. You should check out her blog tellittothedog.substack.com.

In the early weeks of spring, I was on vacation with my family and friends in Barcelona. On a bright sunny day, we went to visit the storied Sagrada Familia, a grand cathedral designed by the Spanish visionary architect Antoni Gaudí. Gaudí is known for his buildings that are imbued with narrative and ornate geometry— often using shapes that are found in nature but that challenge the physical characteristics of building materials such as stone and wood. I have been lucky to visit many stunning houses of worship in my life, but I don’t think I have ever been as awestruck as I was visiting this temple.

The entire story of Christianity seemed like it could crash upon you like an avalanche. The whole basilica could be thought of as a stone bible (1). Visitors enter the church from the Nativity facade, the side of the building that tells the story of the birth of Christ. It seemed that all over four tours and three entrances, the church was bursting with stone foliage and blossoms. In each floral opening, a different aspect of the birth of Christ emerged: Mary and Joseph’s union, the annunciation, the star of Bethlehem, and more. Your eyes could not rest in space because you would see a deer, a cow, a bird, and more and more of the Earth’s animals. The introduction to the church was like a stream of visual drums beating on your eyes, the rhythm and tempo becoming more overwhelming until the speed of visual information reached an unworldly crescendo; and then you could finally enter.

And then exhale.

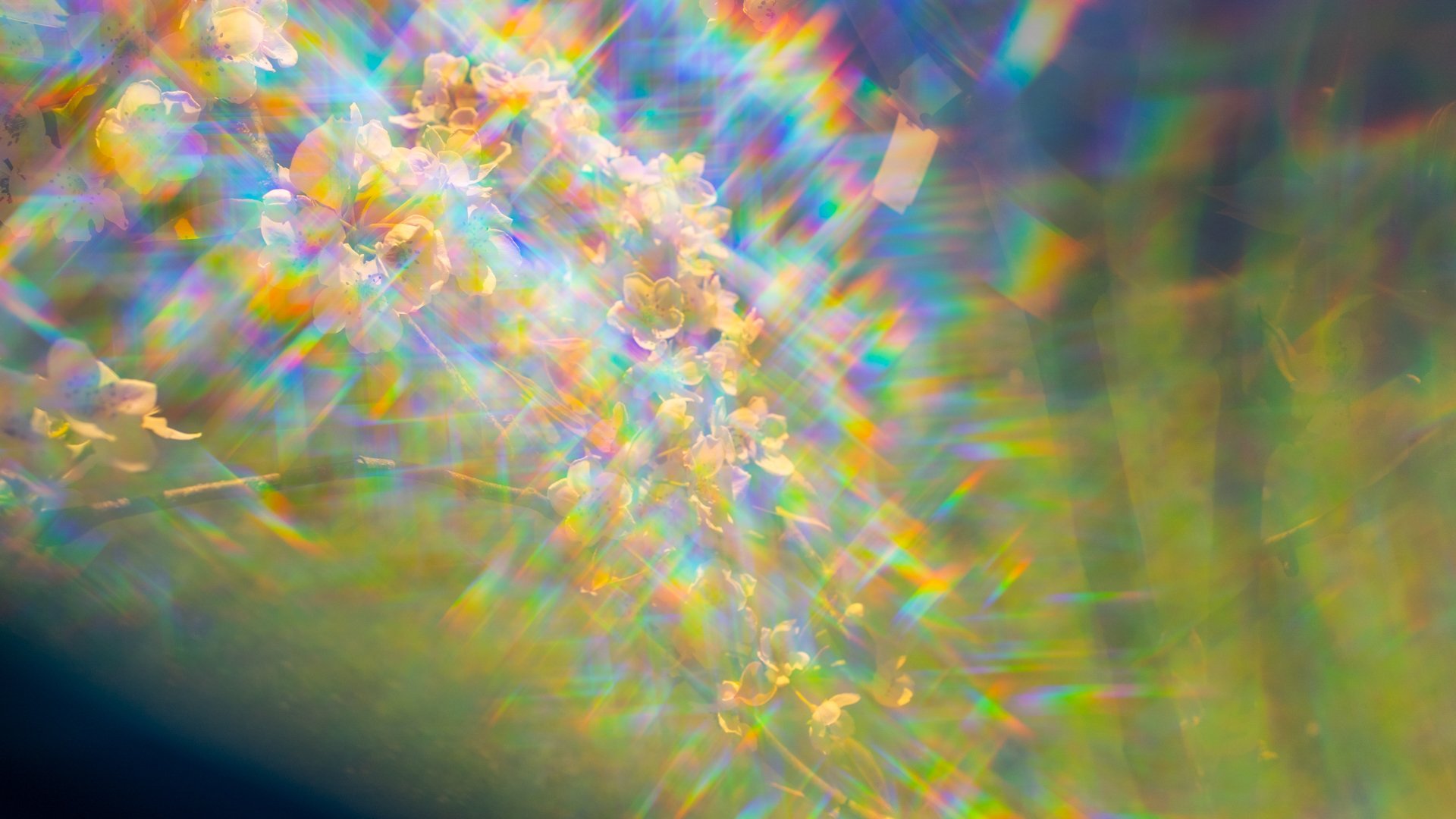

The inside of the Sagrada Familia is very airy with slick stone pillars that look like earth was simply pulled from the ground and flowered into a sunburst once the stems reached the vaulted ceilings. After rolling my head around to look at the many intricacies above, I was drawn to the many stained glass windows that were framed by each pillar. The windows were all made of geometric shapes and boldly filled in with a color of the rainbow in such a way that if you were to step back, all of the windows depicted a rainbow made of clear primary and secondary colors. Even though sunlight was being strained through the colored glass, it felt as if each window was trying to suck you out of the church into an endless rainbow.

My family and I continued to explore the church, entering the sanctuary and admiring the altar of a suspended, crucified Christ with a ring of grapes and lights circling Him. As I looked back to where we came from, the bold stained glass rainbow was no longer seen. Instead, I saw soft rainbows beaming in. Even gradations of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple light flowed into the church’s airspace as if we had found the end of a rainbow.

This experience inspired Martha's Quarterly, Issue 31, Spring 2024, Wrinkle in the Sun. If I had to zero in on what I found so profound at the Sagrada Familia, it was the felt contradiction of materials evoking things that they were not, and therefore challenging the secular side of my ethos to lower its shield and welcome the spiritual. The transformation of distinct colored glass into the experience of a rainbow was so simple, the technology of light and glass appearing before my eyes- no tricks, and yet, the suggestion of faith? Maybe so.

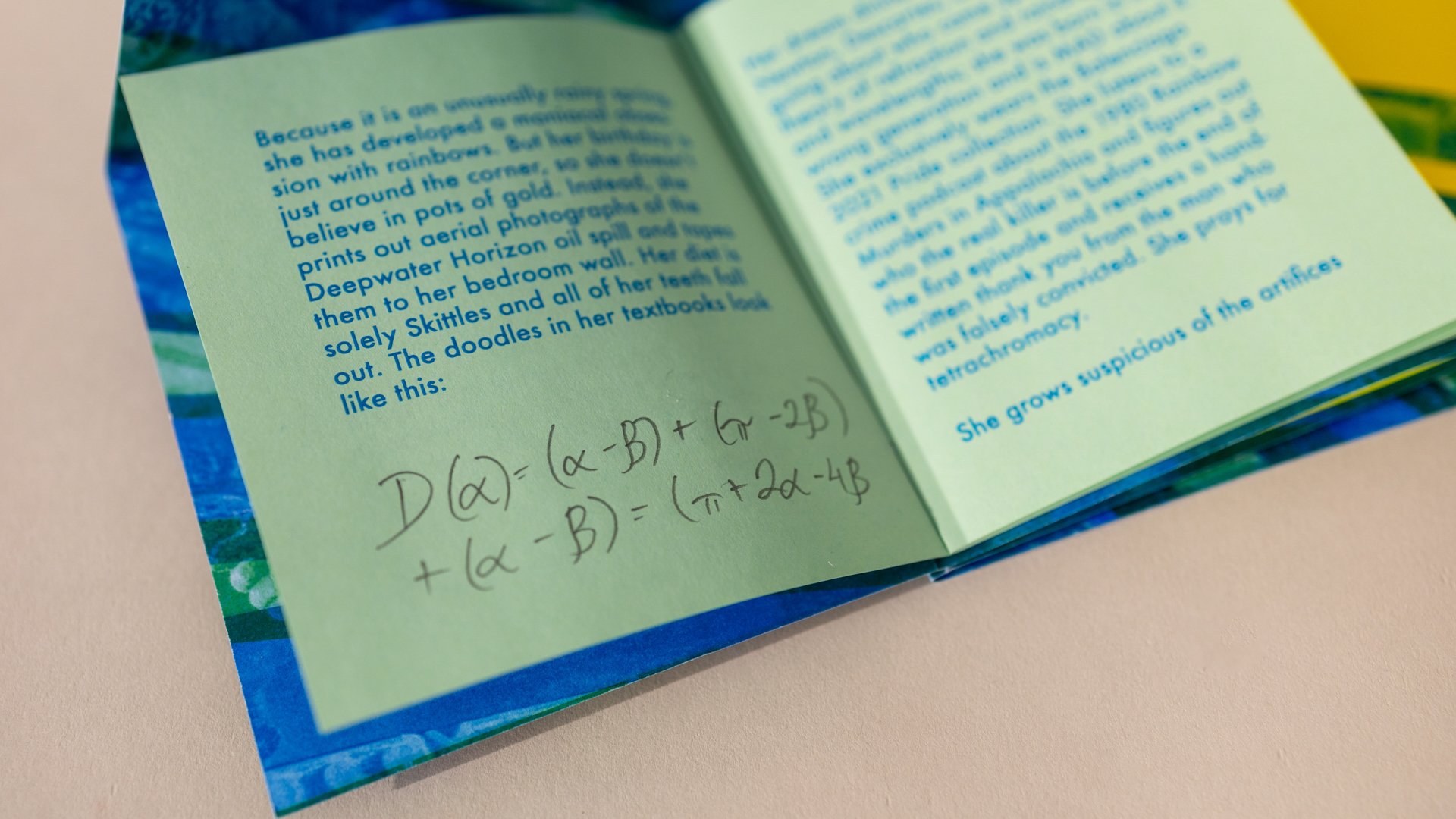

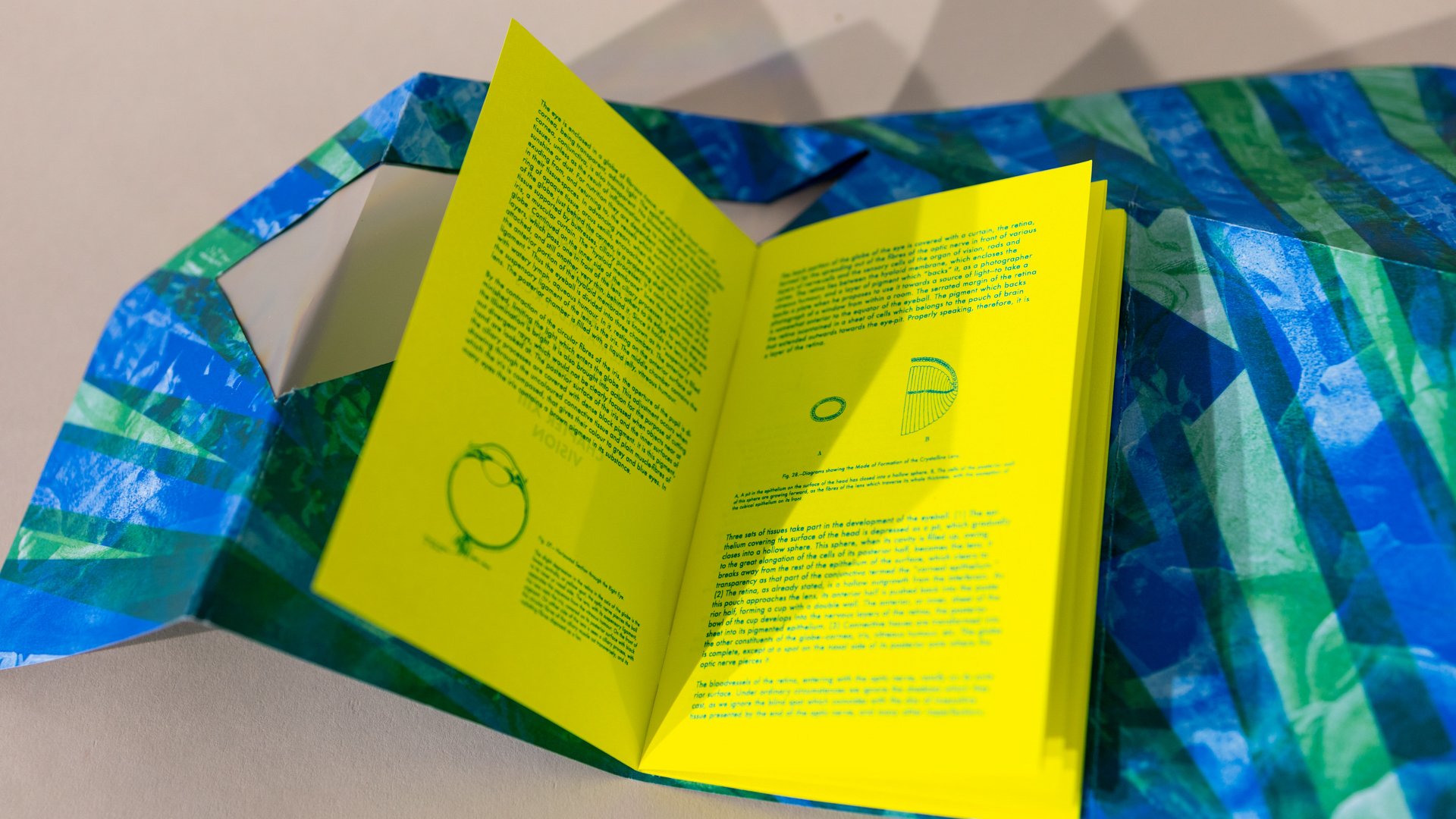

Seeing is believing, right? This is the framework in which I invite you to explore this zine with me. Featured in this Martha’s Quarterly are two pieces of writing embedded in a folded card that has been collaged with the images from the Nativity facade of the Sagrada Familia. The small green pamphlet contains original fiction by the writer Mely Kornfeld commissioned by Passenger Pigeon Press for this zine. We asked Kornfeld to respond in any way to rainbows, and her vignette tells us of an unsatisfied girl and her tepid, yet existential relationship with rainbows. Juxtaposed to this work is an excerpt entitled Vision from the 1908 book A Treatise on the Principles of Physiology by Alex Hill. With clear diagrams and illustrative descriptions, Hill describes the mechanics of these vital organs we use in the seamless act of seeing. Between these two writings, I hope to probe at the query of sight and faith.

When this whole zine is unfolded, there is a triangular window that you can hold up to your eyes. Look through it, and your whole line of vision will be filled with rainbows.

We live in a unique time of slippage, where what we see could align with what we believe, but it very well could not. This happens frequently in the digital space, where we can’t tell the difference between real life and rendered reality. What is special about the rainbow effect in the Sagrada Familia is that the illusion of a rainbow happens in real life through real physical materials you can identify. And, even though it is real, it is simultaneously so unreal that it suggests a level of consciousness we cannot see but could choose to believe in.

-Tammy Nguyen

(1) The Basilica of the Sagrada Familia, Dosde, 2022, pp. 024.

@passengerpigeonpress

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 31, Spring 2024, Wrinkle From the Sun was produced using single-color photocopy, xerox, and laser cutting. Futura Medium font was used in various sizes and styles. The cover paper printed on Springhill blue 147 gsm cardstock. The internal pamphlets were printed on 20 lb. Hammermill green paper and 24 lb. Astrobright neon yellow paper. The paper sleeve was printed on 20 lb. Neenah solar yellow paper. The pamphlet entitled “The Body at Work: A Treatise on the Principles of Physiology, Chapter XIII: Vision” was written by Alex Hill, M.A., M.D., F.R.C.S. and sourced from Project Gutenberg. Mely Kornfeld wrote the short fiction on the green pages. The images on the cover were collaged from The Basilica of the Sagrada Familia. Mely Kornfeld has granted permission for the use of her work in this publication, and “The Body at Work” has been released into the public domain. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen with additional editing from Holly Greene. Production was led by Daniella Porras with assistance from Cheney Hester, Dylan Ng, Lena Weiman, Spencer Klink, and Lexi Radziner.

Hill, Alex. “Chapter XIII: Vision.” The Body at Work: A Treatise on the Principles of Physiology, 1908, pp. 372-403.

Kornfeld, Mely. Untitled, 2024.

Published in April 2024, this is an edition of 250.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 30

Winter 2024The Sun and night are to mortals slaves

5.5” x 4.25”About the contributors:

Origen of Alexandria (185-254 CE) was an early Christian theologian.

David S. (DS) Saunders, (1935-2023) was a scientist who helped the world understand how insects reproduced and adapted to our planet.

John Yau is an American poet and critic based in New York. Born in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1950, Yau attended Bard College and earned an MFA from Brooklyn College in 1978. He has published over 50 books of poetry, artists' books, fiction, and art criticism.

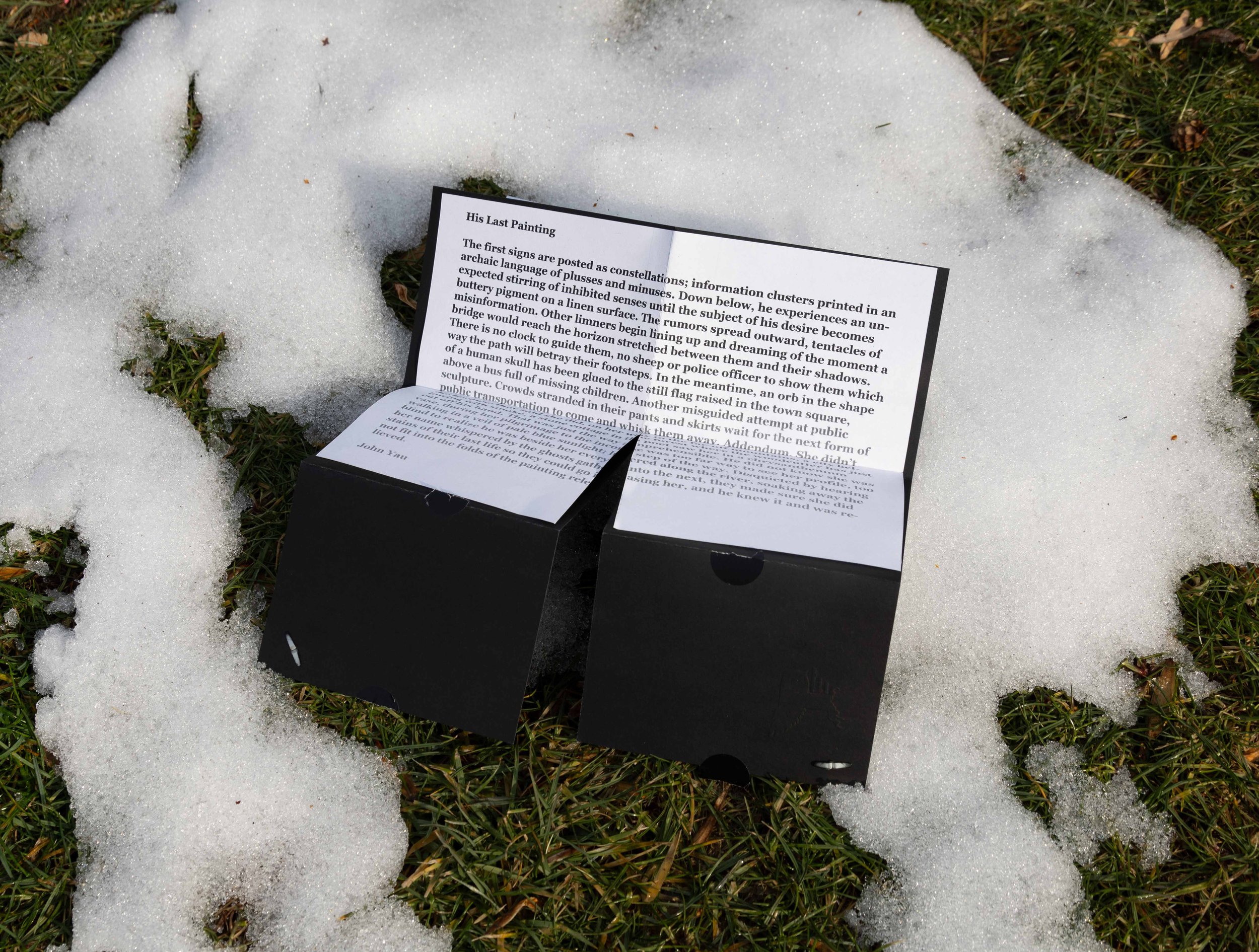

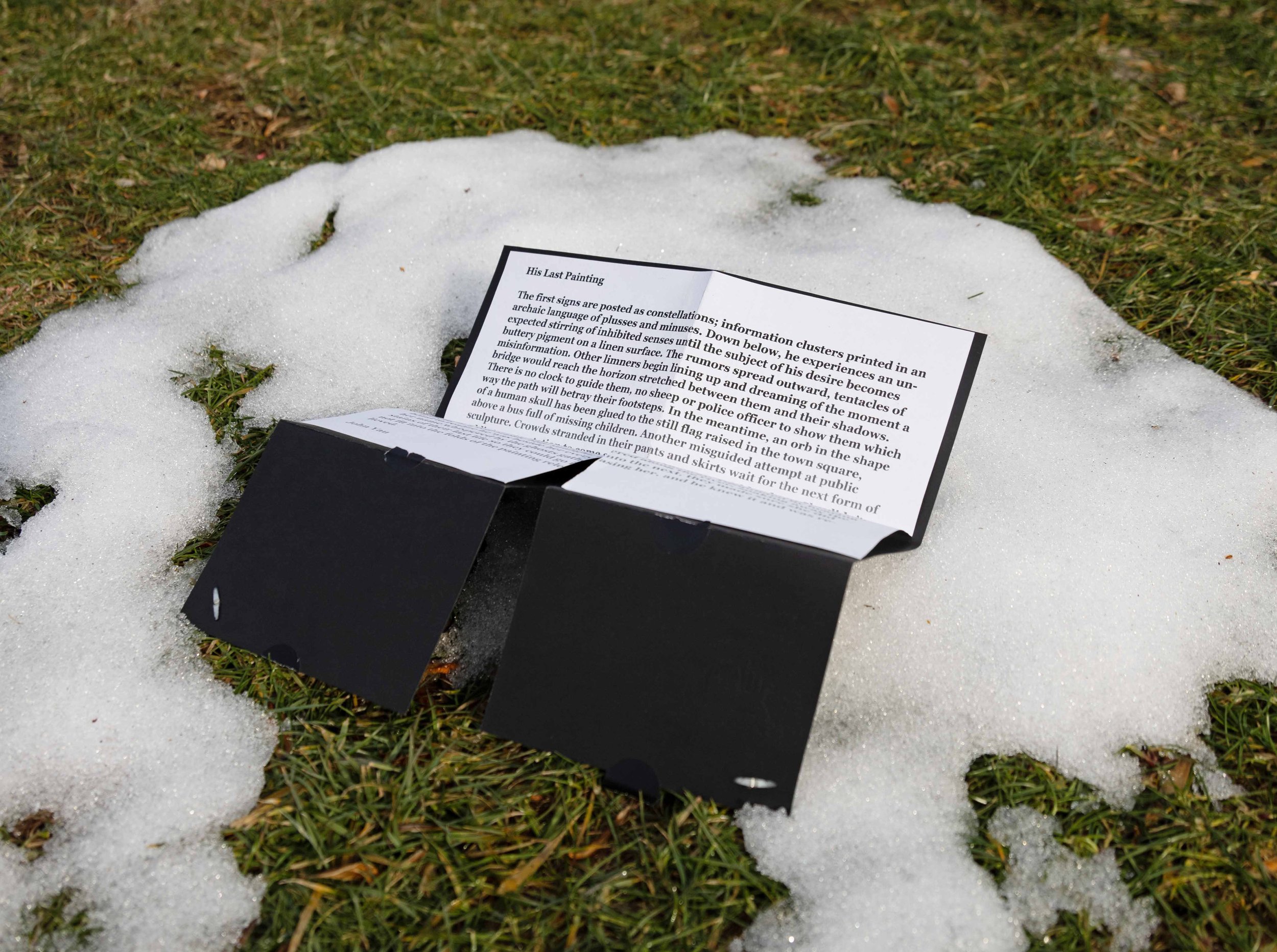

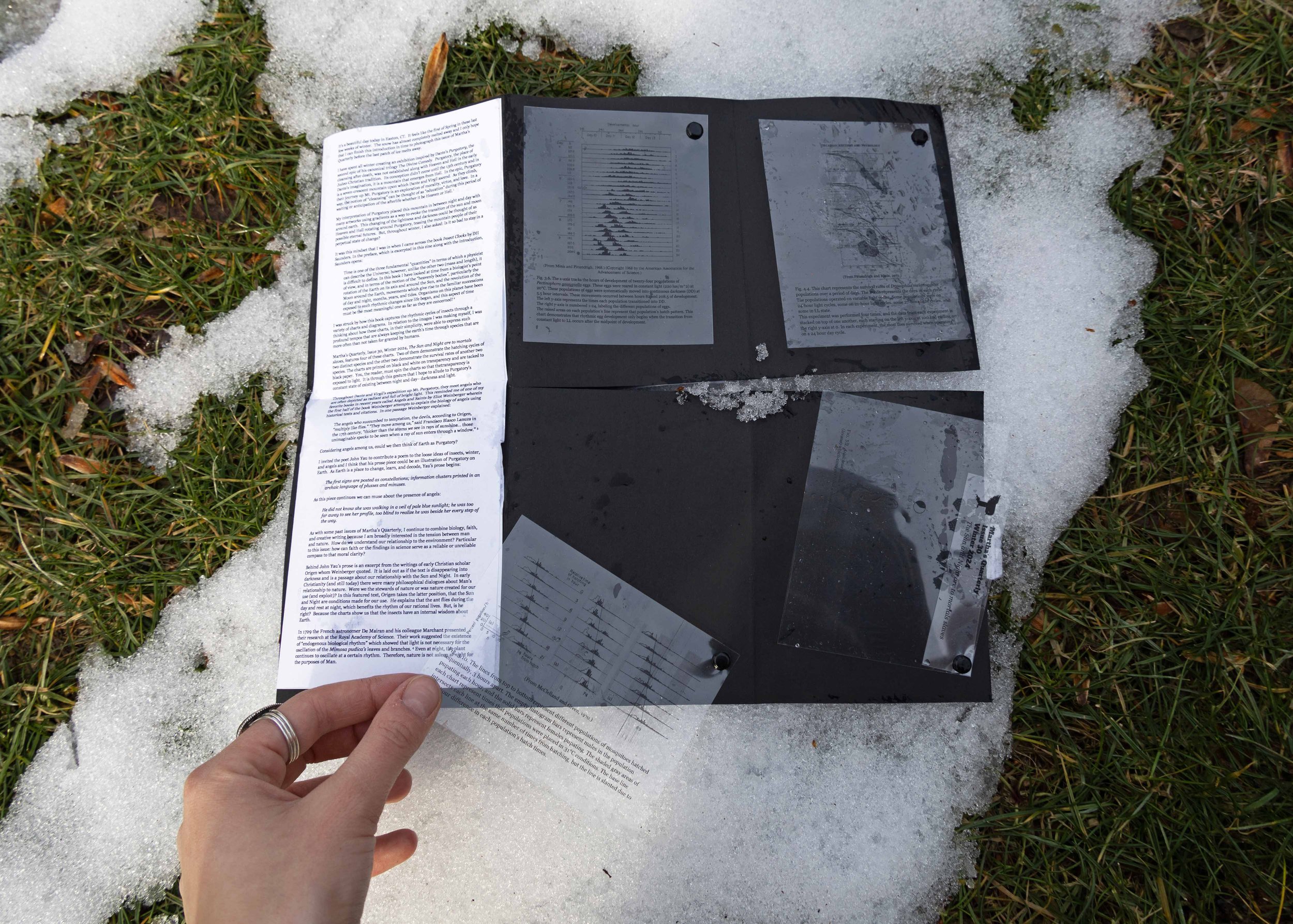

It’s a beautiful day today in Easton, CT. It feels like the first of Spring in these last few weeks of winter. The snow has almost completely melted away and I only hope that I can finish this introduction in time to photograph this issue of Martha’s Quarterly before the last patch of ice melts away.

I have spent all winter creating an exhibition inspired by Dante’s Purgatory, the second epic of his canonical trilogy The Divine Comedy. Purgatory, the place of cleansing after death, was not established along with Heaven and Hell in the early Judeo-Christian tradition. Its conception didn’t come until the 13th century and in Dante’s imagination, it is a mountain that emerges from Hell. In the epic, Purgatory is a seven-crescent mountain upon which Dante and Virgil ascend. As they climb, their journey up Mt. Purgatory is an exploration of morality, virtue, and love. In a way, the notion of “cleansing” can be thought of as “education” during this period of waiting or anticipation of the afterlife whether it be Heaven or Hell. (1)

My interpretation of Purgatory placed this mountain in between night and day with many artworks using gradients as a way to evoke the transition of the sun and moon around earth. This changing of the lightness and darkness could be thought of as Heaven and Hell rotating around Purgatory, teasing the mountain people of their possible eternal futures. But, throughout winter, I also asked: Is it so bad to stay in a perpetual state of change?

It was this mindset that I was in when I came across the book Insect Clocks by DH Saunders. In the preface, which is excerpted in this zine along with the introduction, Saunders opens:

Time is one of the three fundamental “quantities” in terms of which a physicist can describe the Universe; however, unlike the other two (mass and length), it is difficult to define. In this book I have looked at time from a biologist’s point of view, and in terms of the motion of the “heavenly bodies”, particularly the rotation of the Earth on its axis and around the Sun, and the revolution of the Moon around the Earth, movements which give rise to the familiar successions of day and night, months, years, and tides. Organisms on this planet have been exposed to such rhythmic changes since life began, and this aspect of time must be the most meaningful one as far as they are concerned! (2)

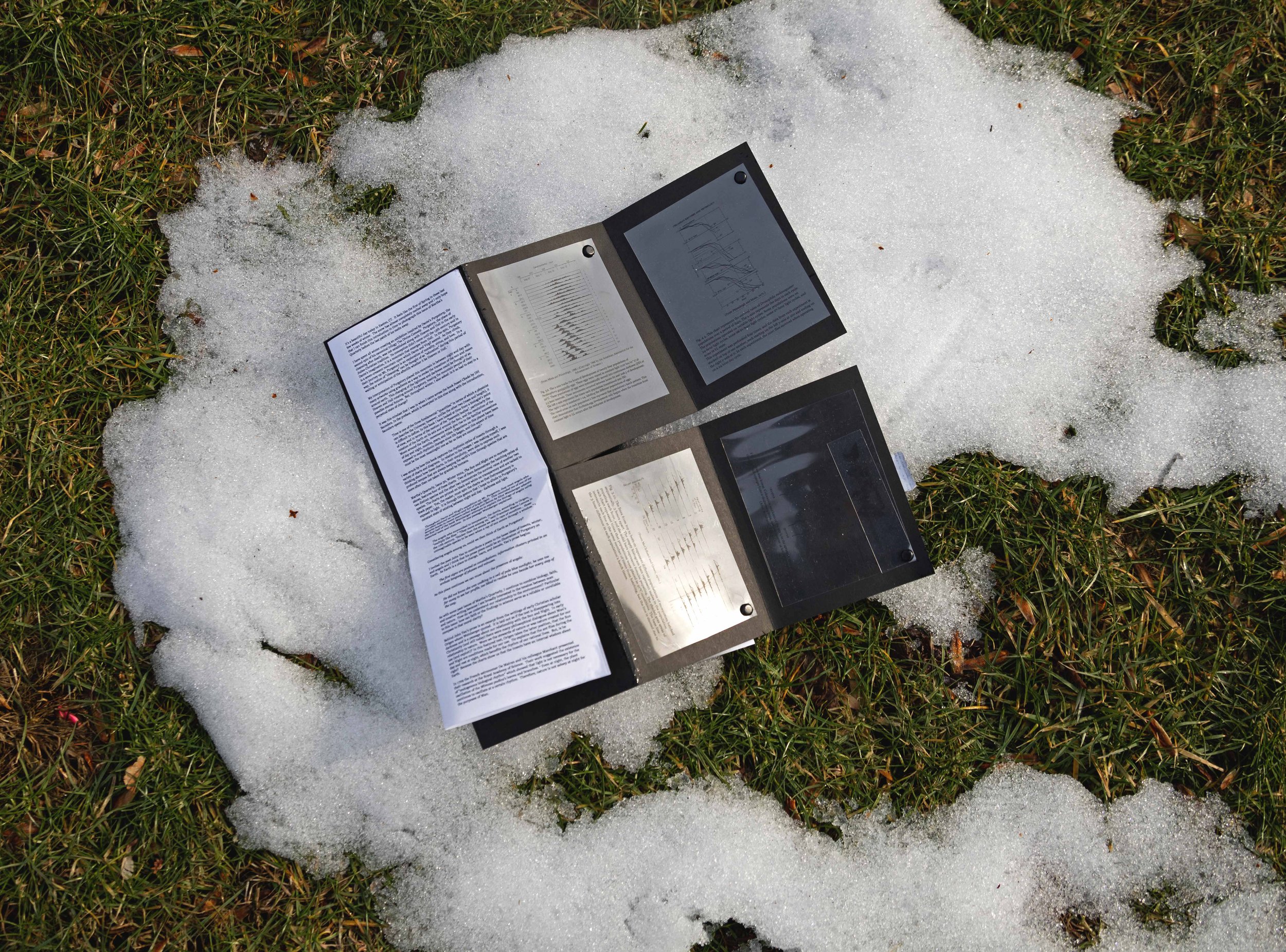

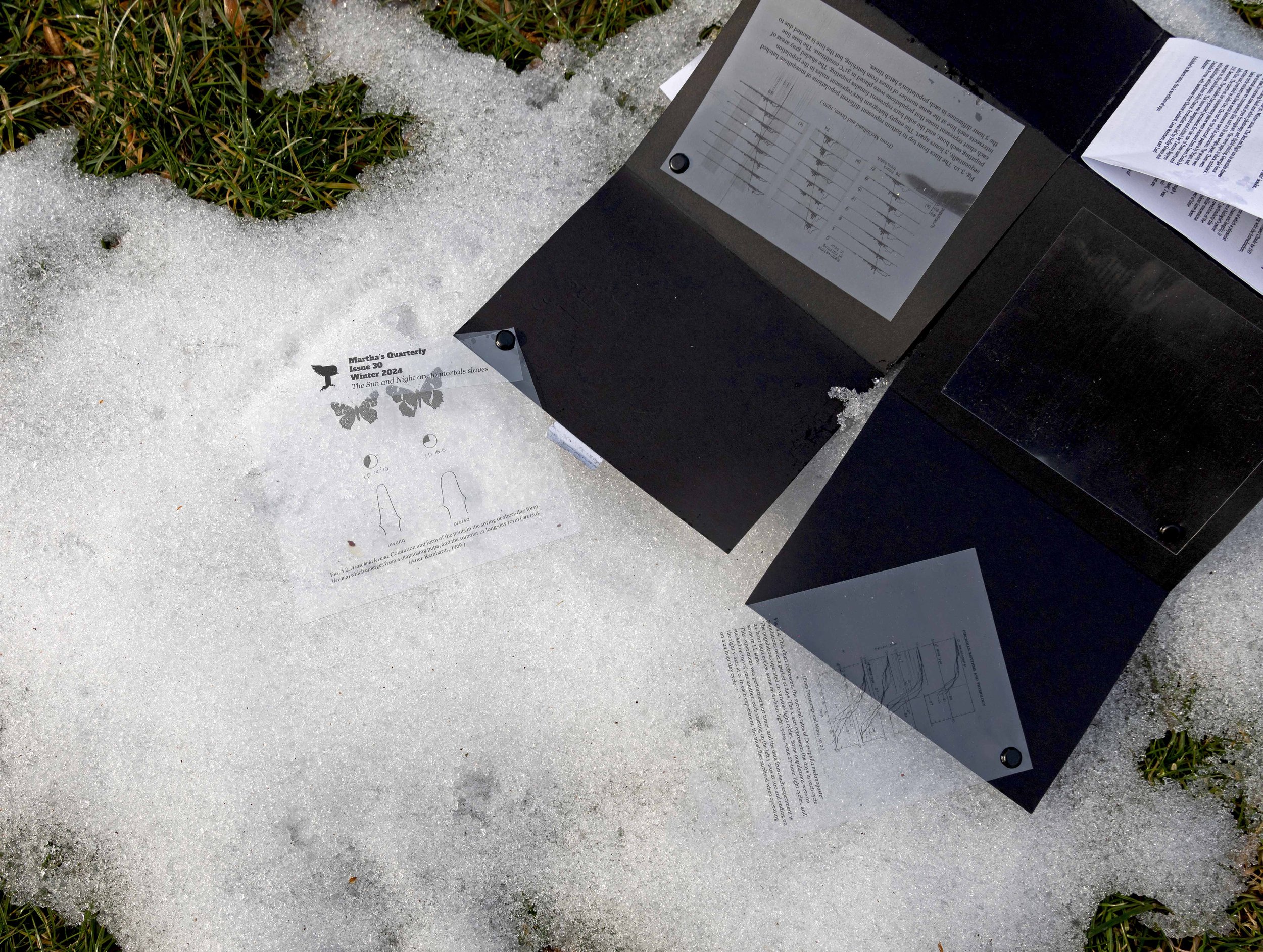

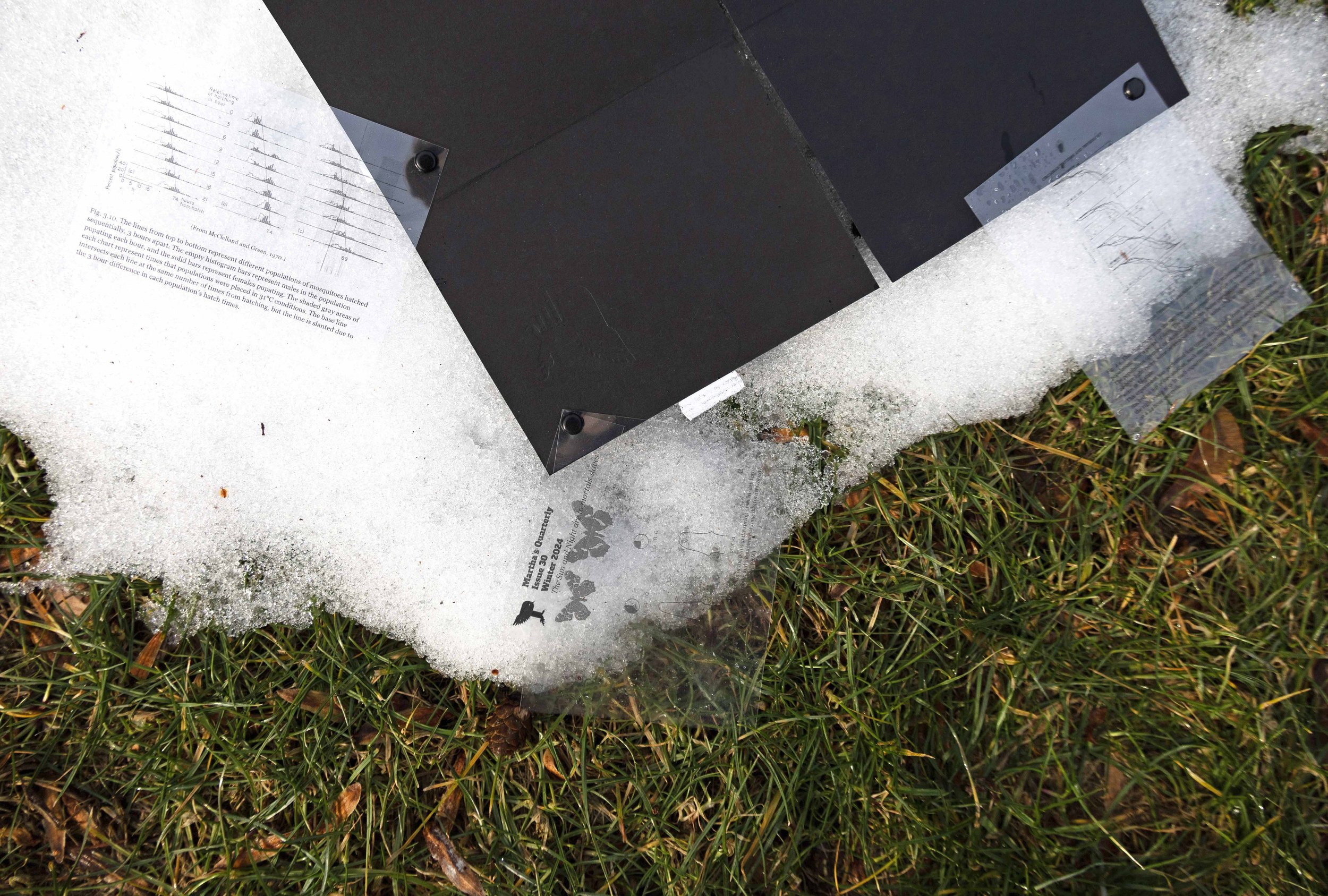

I was struck by how this book captures the rhythmic cycles of insects through a variety of charts and diagrams. In relation to the images I was making myself, I was thinking about how these charts, in their simplicity, were able to express such profound tempos that are always keeping the earth’s time through species that are more often than not taken for granted by humans.

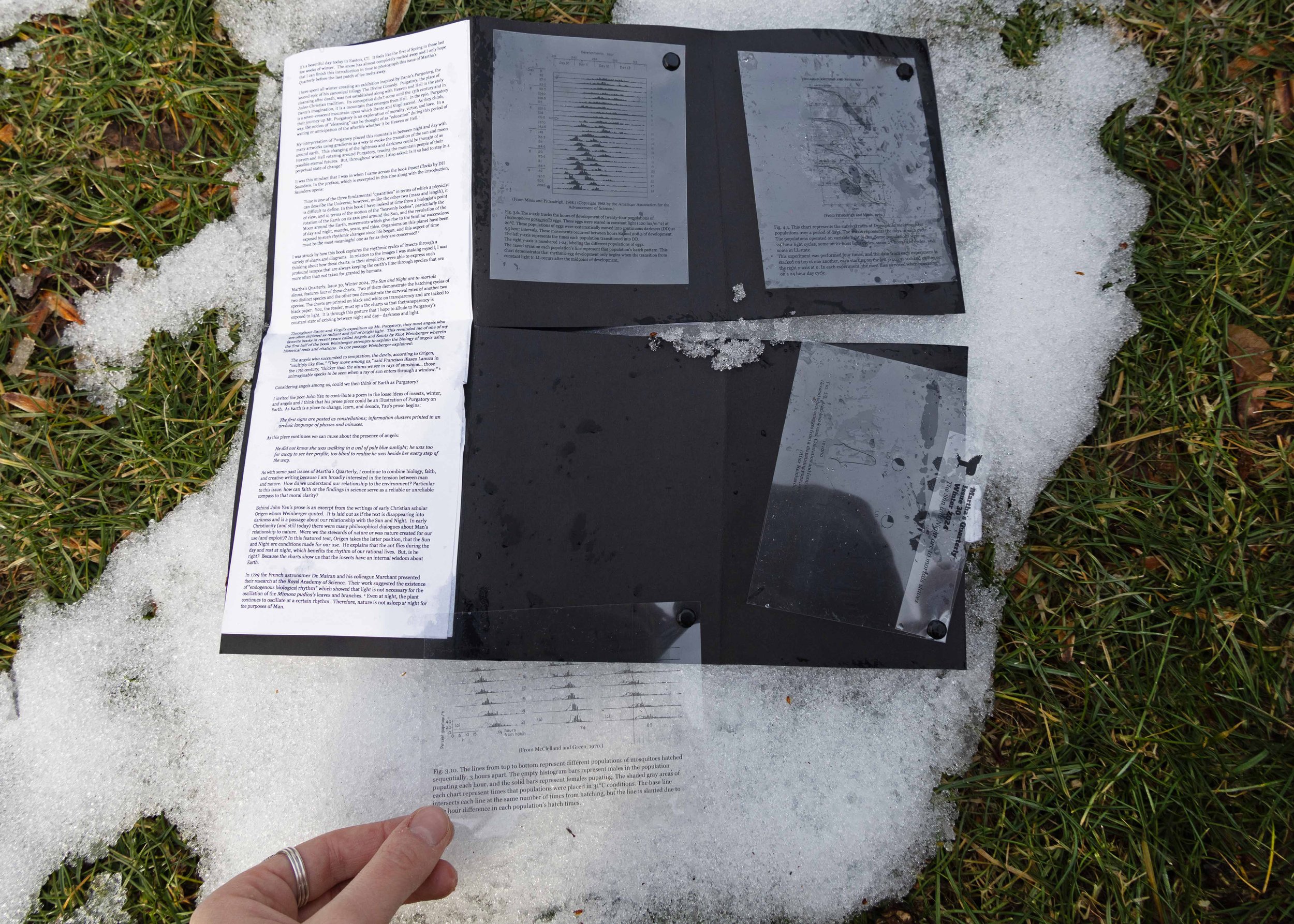

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 30, Winter 2024, The Sun and Night are to mortals slaves, features four of these charts. Two of them demonstrate the hatching cycles of two distinct species and the other two demonstrate the survival rates of another two species. The charts are printed on black and white on transparency and are tacked to black paper. You, the reader, must spin the charts so that the transparency is exposed to light. It is through this gesture that I hope to allude to Purgatory’s constant state of existing between night and day– darkness and light.

Throughout Dante and Virgil’s expedition up Mt. Purgatory, they meet angels who are often depicted as radiant and full of bright light. This reminded me of one of my favorite books in recent years called Angels and Saints by Eliot Weinberger wherein the first half of the book Weinberger attempts to explain the biology of angels using historical texts and citations. In one passage Weinberger explained:

The angels who succumbed to temptation, the devils, according to Origen, “multiply like flies.” “They move among us,” said Francisco Blasco Lanuza in the 17th century, “thicker than the atoms we see in rays of sunshine… those unimaginable specks to be seen when a ray of sun enters through a window.” (3)

Considering angels among us, could we then think of Earth as Purgatory?

I invited the poet John Yau to contribute a poem to the loose ideas of insects, winter, and angels and I think that his prose piece could be an illustration of Purgatory on Earth. As Earth is a place to change, learn, and decode, Yau’s prose begins:

The first signs are posted as constellations; information clusters printed in an archaic language of plusses and minuses.

As this piece continues we can muse about the presence of angels:

He did not know she was walking in a veil of pale blue sunlight; he was too far away to see her profile, too blind to realize he was beside her every step of the way.

As with some past issues of Martha’s Quarterly, I continue to combine biology, faith, and creative writing because I am broadly interested in the tension between man and nature. How do we understand our relationship to the environment? Particular to this issue: how can faith or the findings in science serve as a reliable or unreliable compass to that moral clarity?

Behind John Yau’s prose is an excerpt from the writings of early Christian scholar Origen whom Weinberger quoted. It is laid out as if the text is disappearing into darkness and is a passage about our relationship with the Sun and Night. In early Christianity (and still today) there were many philosophical dialogues about Man’s relationship to nature. Were we the stewards of nature or was nature created for our use (and exploit)? In this featured text, Origen takes the latter position, that the Sun and Night are conditions made for our use. He explains that the ant flies during the day and rest at night, which benefits the rhythm of our rational lives. But, is he right? Because the charts show us that the insects have an internal wisdom about Earth.

In 1729 the French astronomer De Mairan and his colleague Marchant presented their research at the Royal Academy of Science. Their work suggested the existence of “endogenous biological rhythm” which showed that light is not necessary for the oscillation of the Mimosa pudica’s leaves and branches. (4) Even at night, the plant continues to oscillate at a certain rhythm. Therefore, nature is not asleep at night for the purposes of Man.

Nonetheless, these questions are interesting for me to ask in an imagination of Purgatory because we live in such a unique time of change. Right now, there is unbelievable social unrest, brutal global-scale war, and extraordinary technology. Are we able to encompass or engulf the entirety of nature into the embrace of our concepts and ideas? I really do not know, and I know some men think they can.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1) Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy: Purgatorio. Translated by Stanley Lombardo, Hackett Publishing Company, 2016.

(2) Saunder, D.S.. Insect Clocks. Oxford, Pergamon Press, 1976.

(3) Weinberger, Eliot. Angels and Saints. New Directions Publishing, 2020.

(4) https://srbr.org/the-birth-of-chronobiology-a-botanical-observation/

@passengerpigeonpress

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 30, Winter 2024, The Sun and Night are to mortals slaves was produced using black and white photocopy and digital printing. Georgia fonts were used in various sizes and styles throughout. The cover paper is black cardstock. The internal pages are transparency film and 20 lb text weight paper. There were black circle stickers and black metal fasteners used in production. The poetry was written and provided by John Yau. The text on the internal pages is by Origen and John Yau. The charts on the transparency pieces were sourced from Insect Clocks by D.S. Saunders. The publisher has granted permission for the use of these charts and excerpts in this publication. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen with additional editing from Holly Greene. Production was led by Holly Greene and Daniella Porras, with assistance from Chance Lockard, Lena Weiman, and Lexi Radziner.

Published in March 2024 and mailed out in May 2024, this is an edition of 250.