MQ 2023

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 29

Fall 2023

Whereon by a thorn

8.5” x 5.5”About the contributors:

Aniket De is a historian and ethnographer of borders, rivers, and peasant performances in South and Southeast Asia. He is currently completing his PhD in the history of race and South Asian decolonization at Harvard.

Edward Lear was an English artist, illustrator, musician, author, and poet who lived from 1812-1888. He is best known for his nonsense prose and poetry and is widely credited with popularizing the limerick as we know it today.

So far in my life, I have been dealt a good hand in moral luck, a term introduced in Western philosophy by Bernard Williams and developed with Thomas Nagel. The idea essentially is that our moral agency-- how we elect right and wrong, pass ethical judgment, and make moral decisions-- is not completely in our control. Rather, our way of acting out our morality is relative and reflective of the circumstances we happen to find ourselves in. The gift of good health and being born in a time of peace, for example, are all situations that we do not determine (at least not in their entirety.)

This is why the distinction that I am a first-generation Vietnamese-American is important. My parents were Vietnamese War refugees in 1978. They fled Vietnam by boat where they found themselves on Pulau Galang, a refugee camp in Indonesia. There was a Christian family in Virginia that sponsored their immigration to America, then they settled in San Francisco in 1980 and I was born in 1984. These years are notable because the political climate, period of peace, and a good economy in America that followed the fall of Saigon in 1975 all shaped my life and indirectly, the opportunities that I was given. Naturally, I am always interested in the Vietnamese-American war. As I learn, I become more confused by what happened and why because there are thousands of facets woven into this incredible conflict.

In the weeks of this Fall season, my phone has been flooded with thousands of images about and related to the hot war between Israel and Hamas. There are images from news outlets reporting about events on the ground such as the collapse of hospitals and individuals who have lost their entire families in an instant. There are also many other images that encourage activism, informing publics about protests and phone numbers of elected representatives. Then, there are some images from civilians in Gaza and Israel, and some of them have shown unspeakable evidence of human cruelty.

I have thought a lot about my own moral luck in this new “fog of war”, a term that is not a direct quote, but an evolution from Carl von Clausewitz’s 1873 book, On War, where he said, “War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.” The decisions being made by Israel, Hamas, and the entities directly and indirectly related to this conflict are being calculated in a state of chaos and high stakes, where one decision affects not just the lives of the living, but the lives of the next generations. For me, I am doing my best to learn about the history of this region and why the boundaries of Gaza have been so vulnerable and fragile.

The space between “moral luck” and the “fog of war” is where I want to consider the seemingly unrelated elements of this Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 29, Fall 2023, Whereon by a thorn. This installment features four English limericks from Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense from 1846 and some passages from the book The Boundary of Laughter by the historian Aniket De from 2021. One reason why I wanted to juxtapose these two writings in the context of this contemporary moment was to explore the idea of lightness and laughter as a way to find clarity-- or find light-- when situations are hard to understand, whether it is because of one’s direct experience of trauma or one’s attempt to understand the depths of human despair because of their own moral luck.

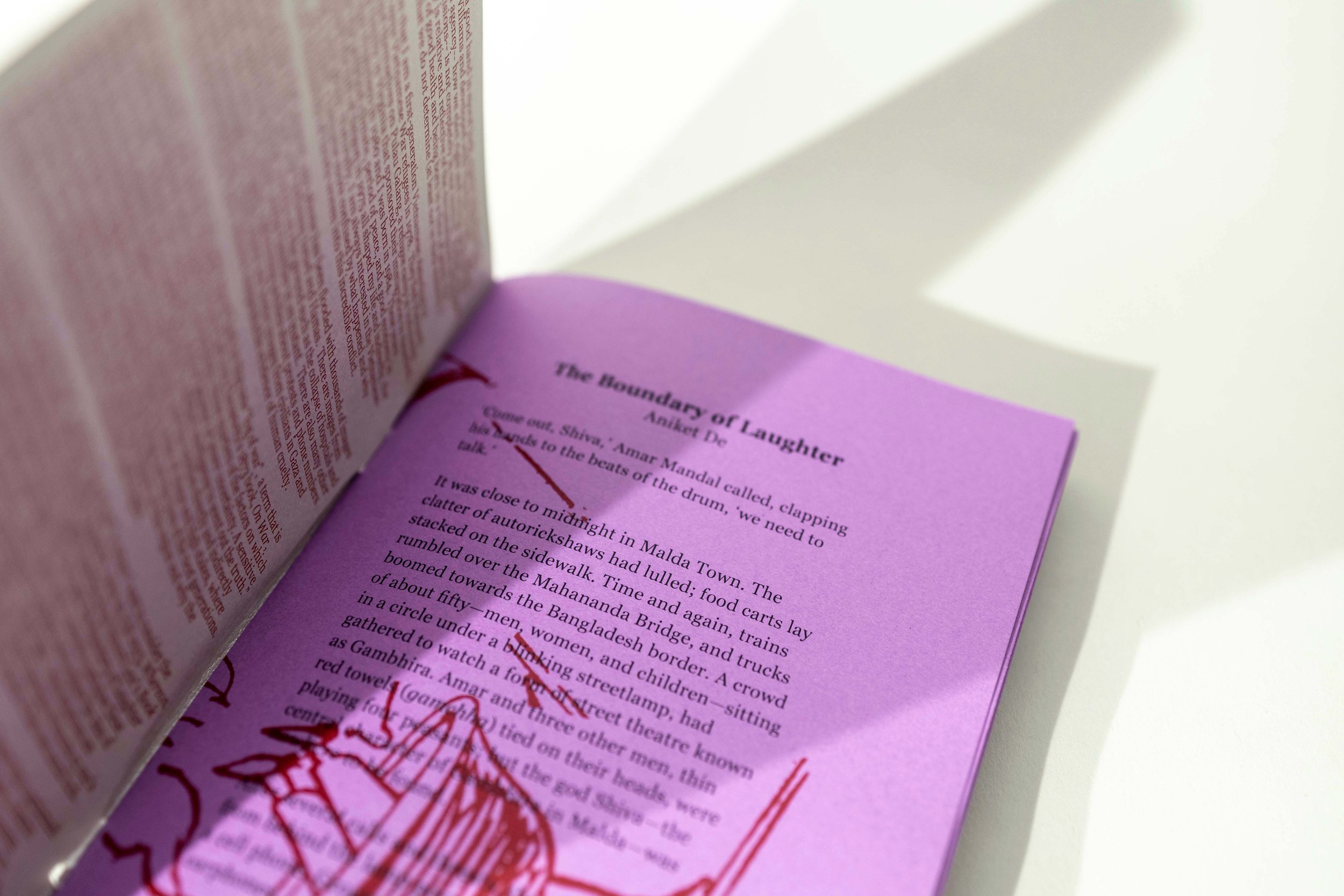

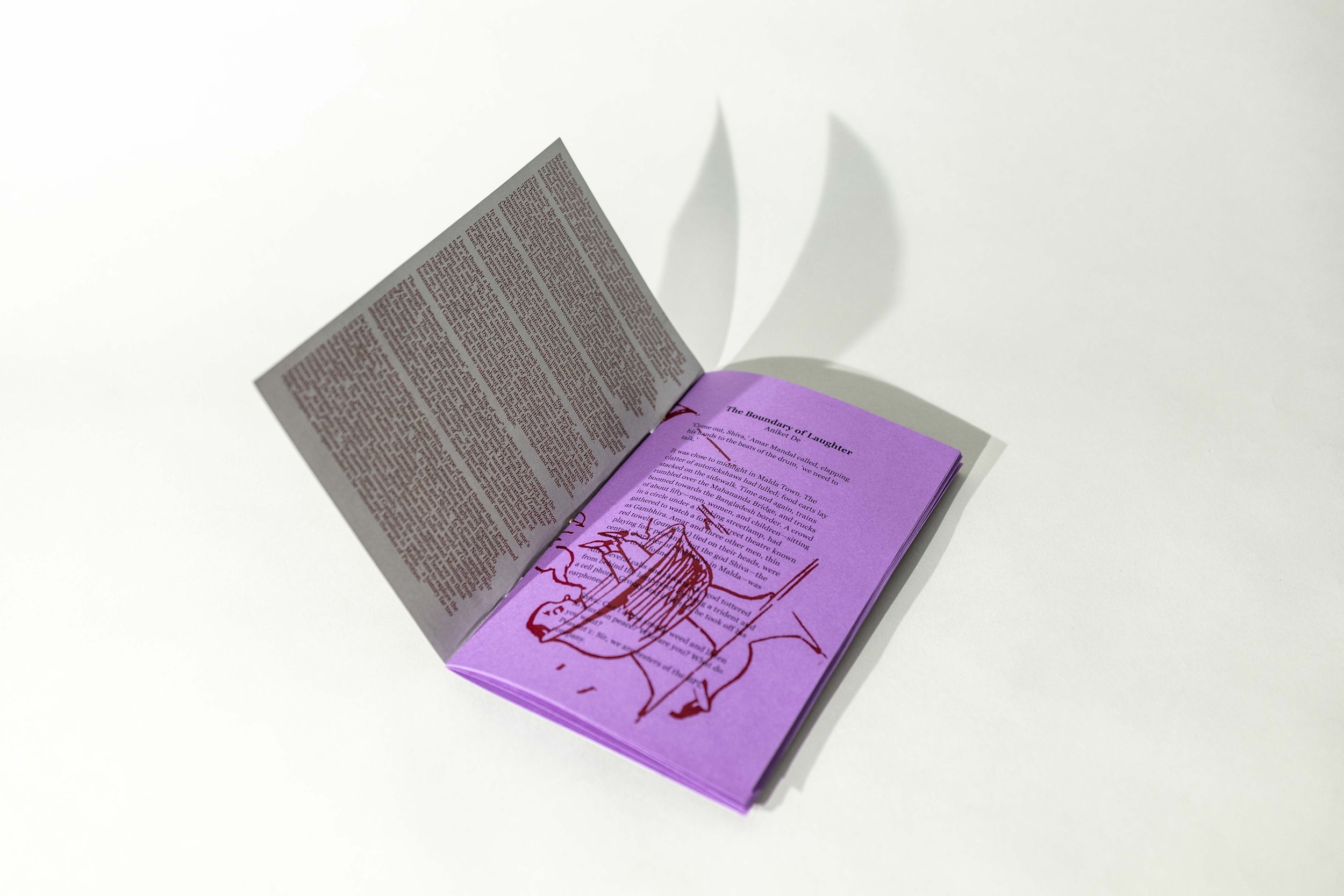

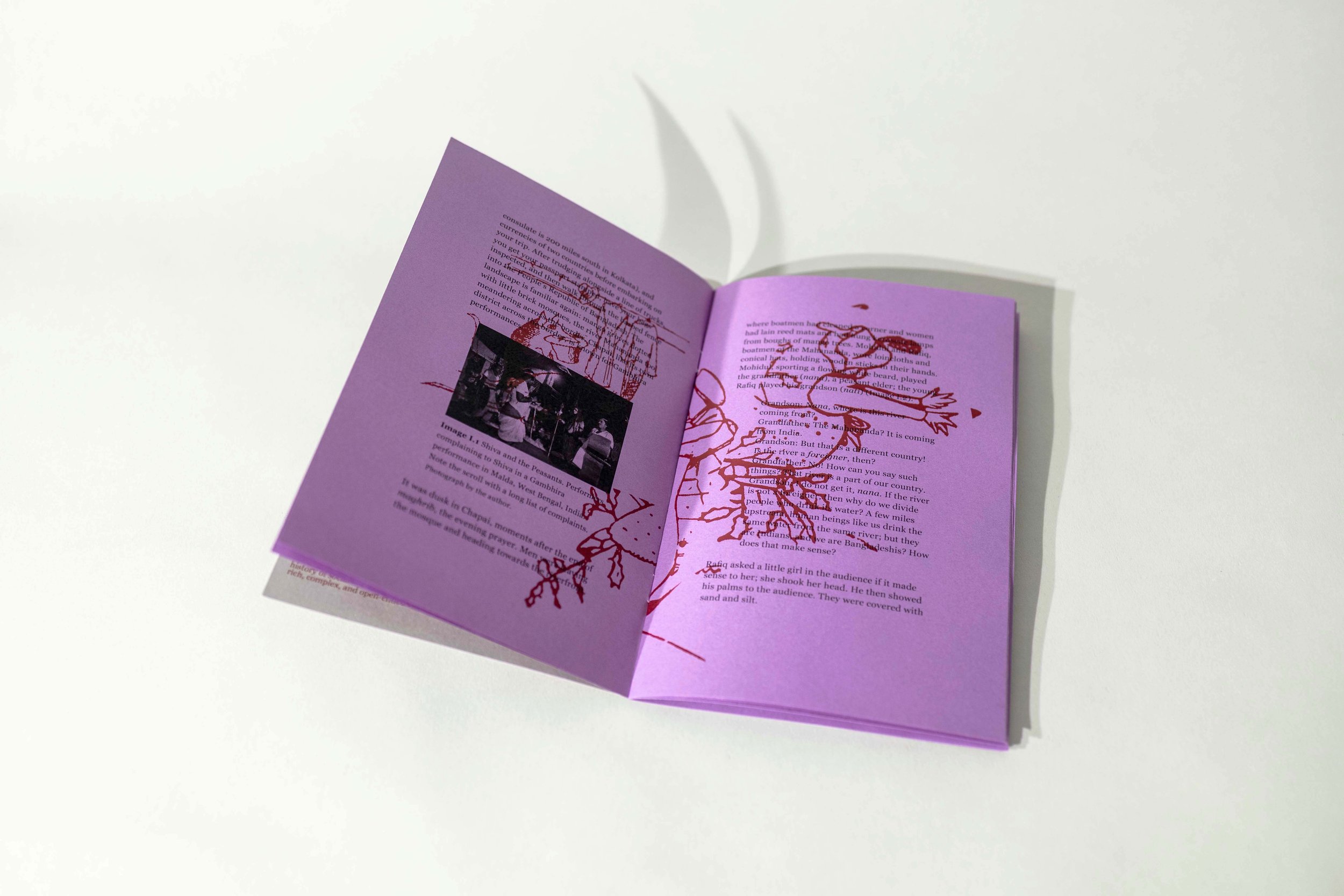

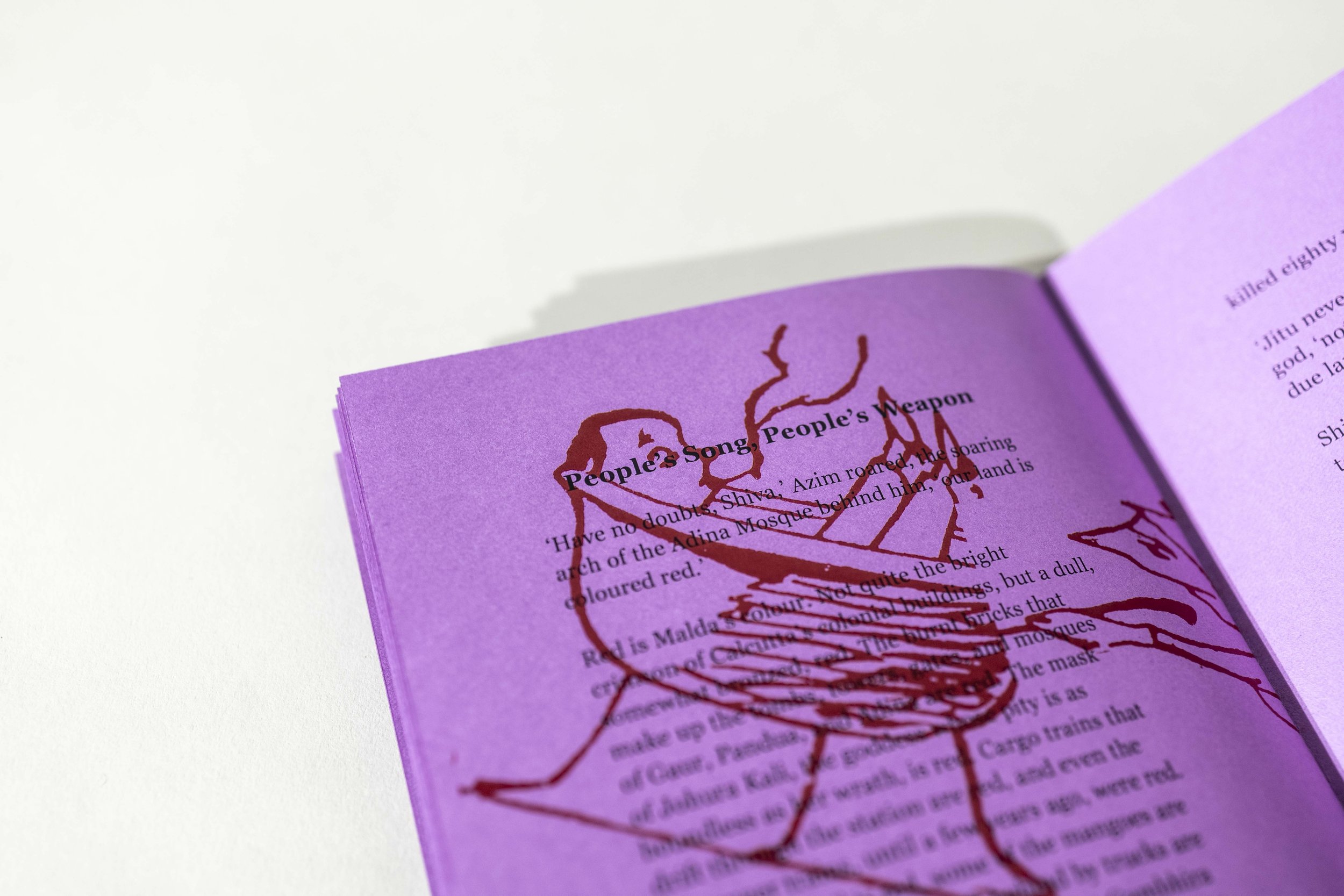

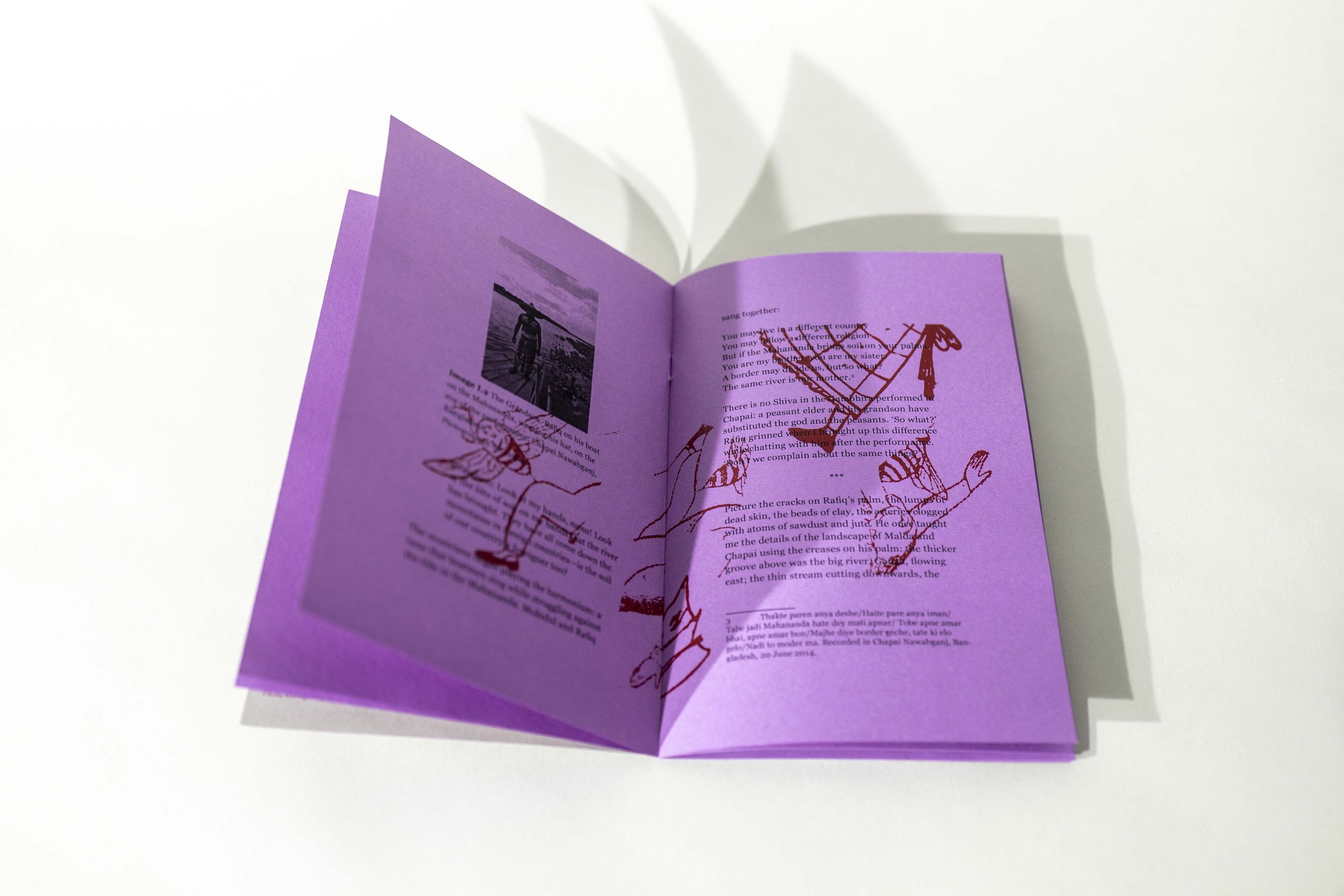

De’s book is about the tradition of Gambhira, a type of street theater that is performed in Malda Town, a district in West Bengal (India) and Chapai Nawabganj, a district in Bangladesh. In many of these performances, peasants are featured expressing their plight, often in a comical way. The performances bring light and lightness to realities that are undesirable, even harsh. In Malda, where people are mostly Hindu, the peasant characters are seen complaining to the god Shiva. In Chapai Nawabganj, where people are mostly Muslim, the peasant characters throw their woes against their grandfather. The performances are essentially the same, as the world of Gambhira is much older than the boundary between Bangladesh and India which was artificially created in 1947 in the British Partition, where lines crudely separated Muslims from Hindus. De’s work spotlights this beautiful performance tradition as a way to think more elaborately about nationalism, community, and the notion of border more broadly. As he puts it, “The shared space of Gambhira is a useful lens to explore the history of social relations between Hindus and Muslims in Malda— a history far too rich, complex, and open-ended to be reduced to the telos of Partition.”

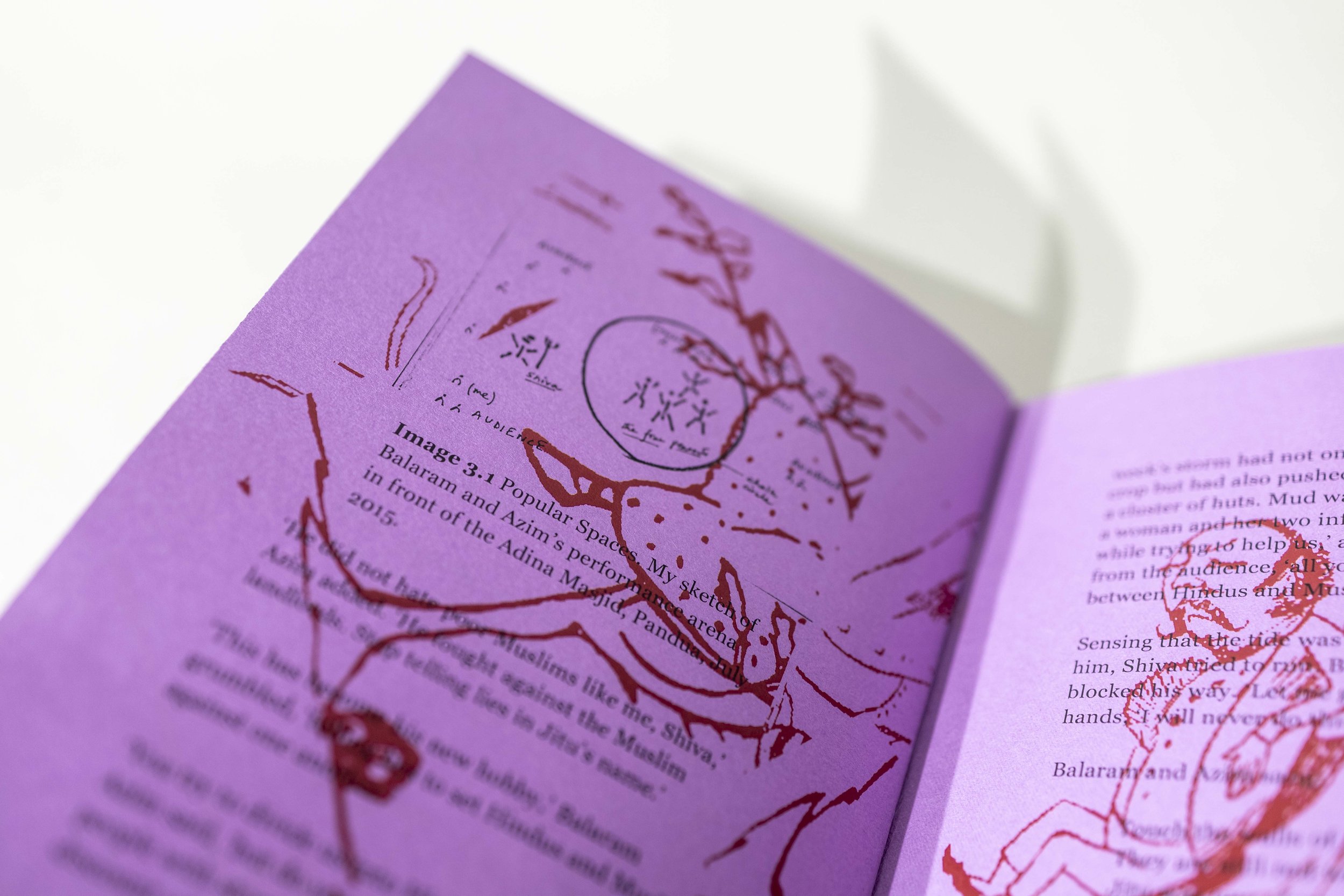

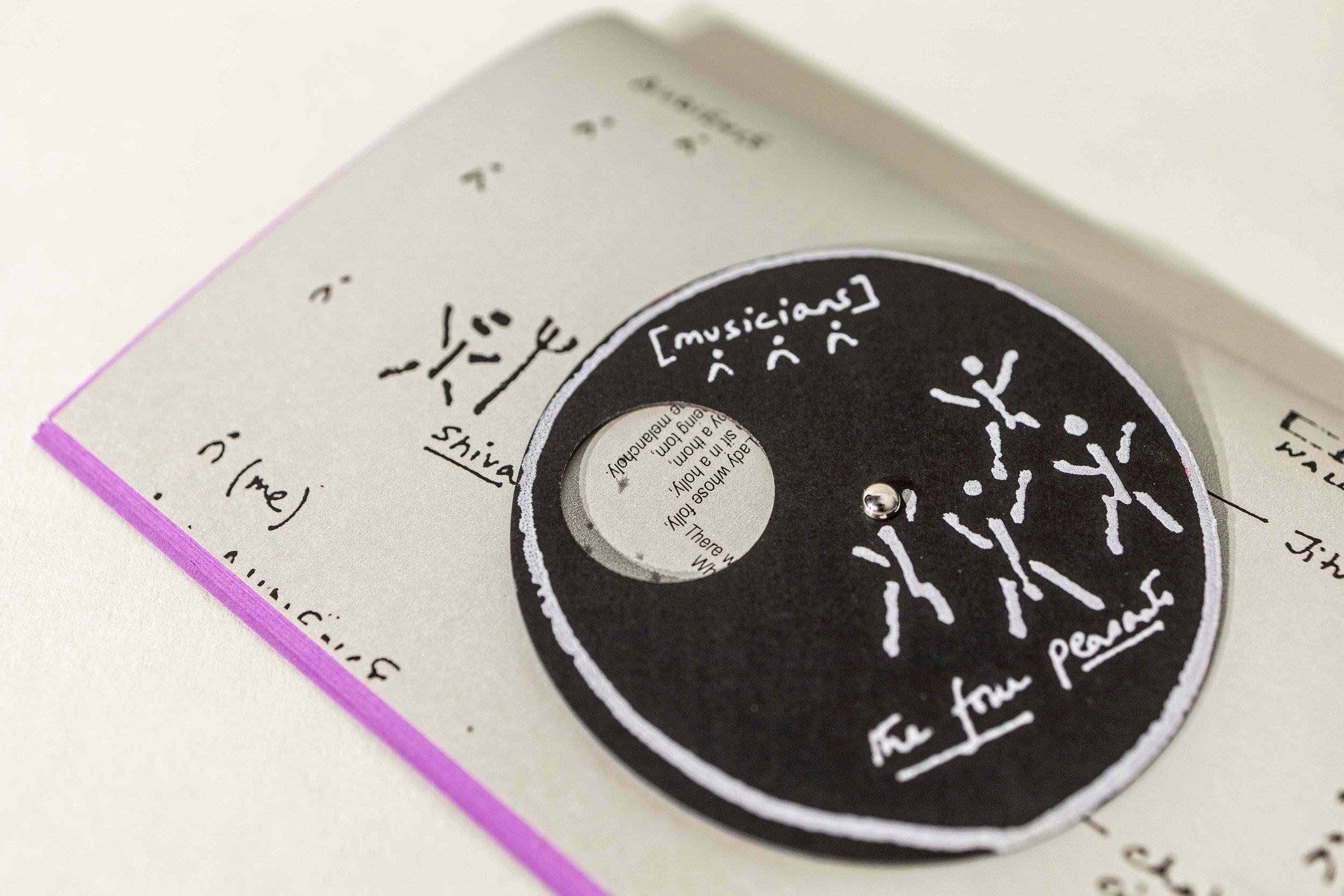

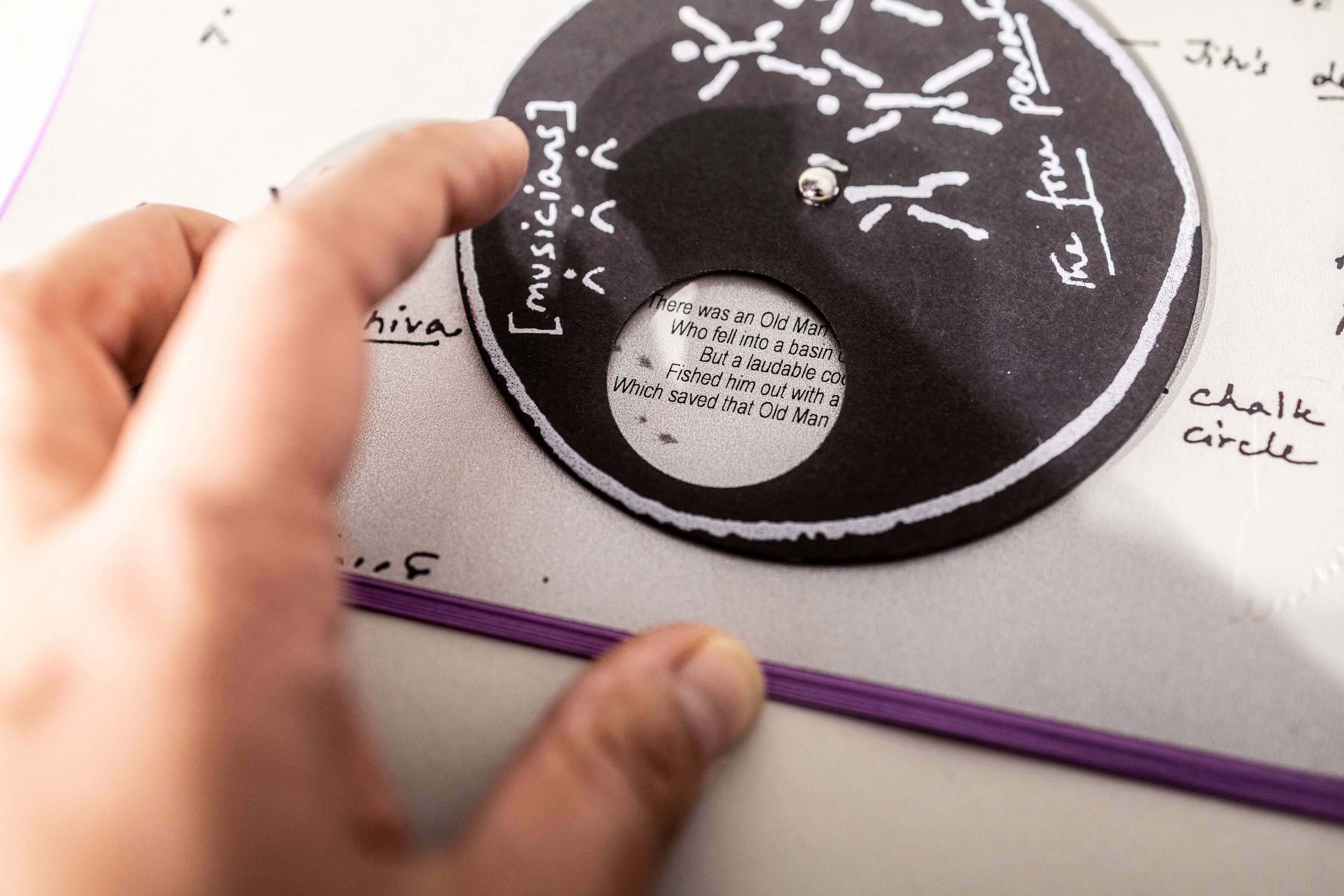

De’s book features plenty of Gambhira images, and among them are his own drawings of the performances which we have appropriated on the back side of this zine. De’s diagram illustrates a performance that took place in Adina Masjid, Pandua in July 2015. The skit, in some ways, points to the folly of distinguishing a Muslim from a Hindu, as Azim, one of the characters exclaims, “‘You try to divide us into Hindu and Muslim [...] but do you discriminate when you kill people with storms and lightning? Do Hindus get a discount when you destroy mango harvests?” The center stage is a circle, and we have created a spinning wheel out of it. As you turn the wheel, four English limericks appear demonstrating the plight of four unlucky people.

England-- or Great Britain-- was the colonial empire of many parts of South Asia. But in the context of this quarterly, the characters of these seemingly silly poems could be any person. The origin of the limerick is unknown, but there have been suggestions that the word comes from an 18th-century Irish song, “Will You Come Up to Limerick” wherein the lyrics included absurdities and innuendo. The Edward Lear limericks we have selected are some of the earliest funny poems of the genre. Published with them were illustrations which we have appropriated and collaged all over this zine. The situations in the poems are nonsensical, and they each feature a person in a state of helplessness. By presenting these poems with De’s work, I wanted to probe at humor’s great power to spread empathy across borders and even oppositional sides.

It is news to no one that we currently live in a time of great divides. I worry about these schisms and have fear about how these ideological conflicts will unfold, evolve, and implode. But I’ll end with this memory from 2008 when I was living in Saigon. I was with my friend at his house when his older brother by almost a decade was also hanging out. My friend's brother had an infectious sense of humor. I don’t remember how we got to talking about it, but my friend’s brother started talking about his experience of the Vietnam War, something that neither my friend nor I knew firsthand. Holding a Saigon beer in one hand and a Red Craven cigarette in the other, my friend’s brother laughed, “God damn it! I ran so fast, but they still caught me. Dad said, let’s just try to get away from these Communists, so we ran towards the beach and jumped into some floating barrels. Who cares! Just go for it! Well, it didn’t work, and I am still here.”

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

De, Aniket. The Boundary of Laughter: Popular Performances across Borders in South Asia, Oxford University Press, 2021.

Lear, Edward. A Book of Nonsense, 1846.

von Clausewitz, Carl. On War. Translated by J. J. Graham, Wordsworth Editions, 1997.

@passengerpigeonpress

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 29, Fall 2023, Whereon by a thorn was produced using black and white and single-color photocopy, digital printing, and silkscreen. Georgia and arial fonts were used in various sizes and styles throughout. The cover paper is 80 lbs text weight, and the internal pages are 20 lb text weight. The limericks and illustrations are sourced from The Book of Nonsense by Edward Lear (1846). The text on the internal pages was written by Aniket De in his book, The Boundary of Laughter. The map and images on the cover and the images on the internal images were sourced from The Boundary of Laughter. Aniket De has granted permission for the use of his work in this publication. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen with additional editing from Holly Greene. Production was led by Holly Greene with assistance from Daniella Porras, Chance Lockard, and Spencer Klink.

Published in November 2023, this is an edition of 250.

Martha's Quarterly

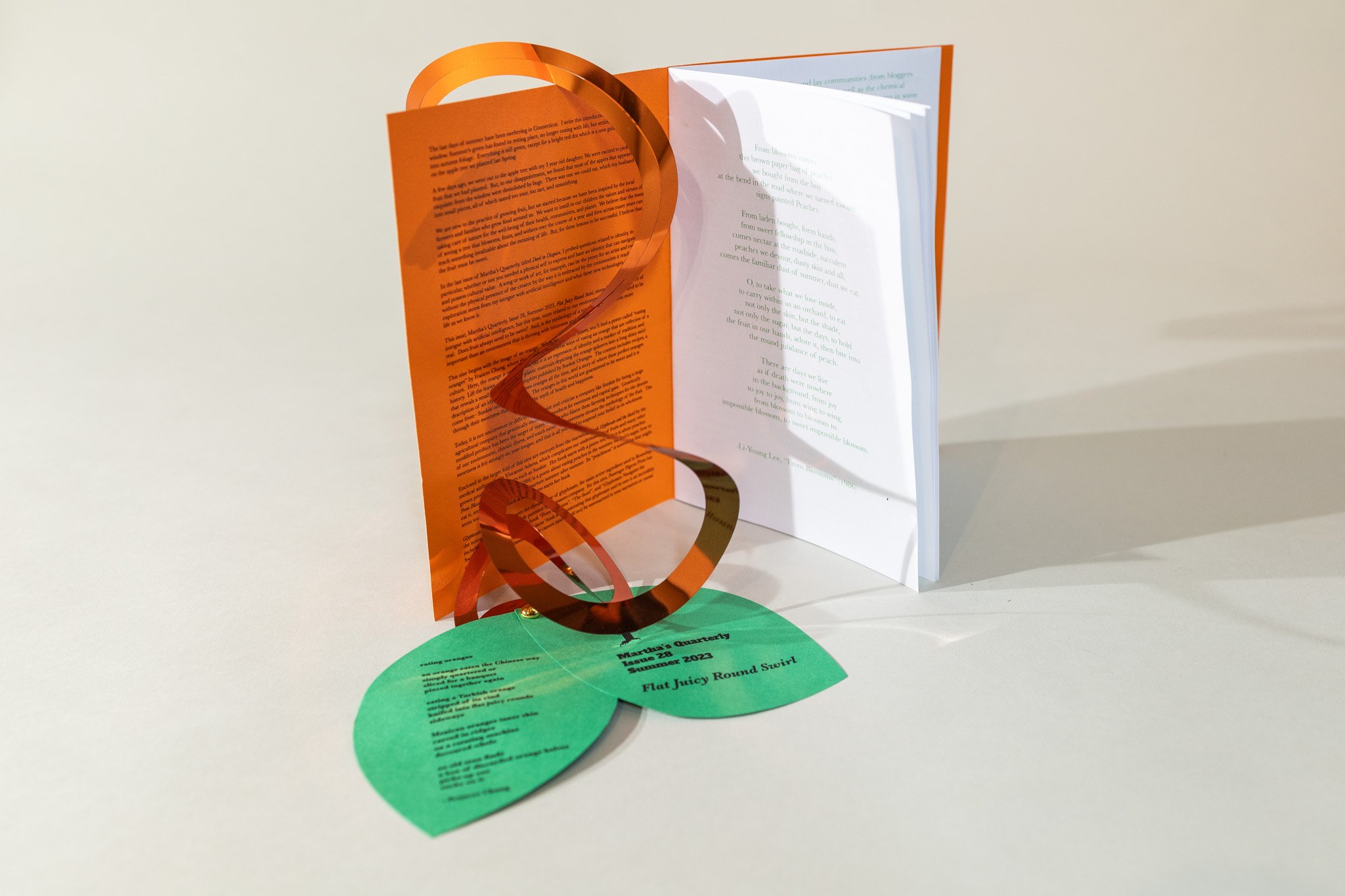

Issue 28

Summer 2023

Flat Juicy Round Swirl

8.25” x 5.75”

About the contributors:

Vincanne Adams is a medical anthropologist at UCSF whose research, books and articles explore a wide range of contemporary predicaments, from the use of metrics in global health and medical pluralism in Nepal and Tibet to disaster recovery in New Orleans and, more recently, the impact of industrial agrochemicals on life, knowledge and politics.

Frances Chung was an American poet born in 1950 and raised in Chinatown, New York. Chung taught math in NY public schools and published her poetry in several anthologies and journals throughout her life. Her collected poetry was published posthumously in 2000 in an anthology entitled, Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple.

The last days of summer have been sweltering in Connecticut. I write this introduction looking out my window. Summer's green has found its resting place, no longer oozing with life, but settled, ready to disappear into autumn foliage. Everything is still green, except for a bright red dot which is a new gala apple ripening on the apple tree we planted last Spring.

A few days ago, we went out to the apple tree with my 3 year old daughter. We were excited to pick the new fruit that we had planted. But, to our disappointment, we found that most of the apples that appeared exquisite from the window were demolished by bugs. There was one we could eat, which my husband cut into small pieces, all of which tasted too sour, too tart, and unsatisfying.

We are new to the practice of growing fruit, but we started because we have been inspired by the local farmers and families who grow food around us. We want to instill in our children the values and virtues of taking care of nature for the well-being of their health, communities, and planet. We believe that the lessons of seeing a tree that blossoms, fruits, and withers over the course of a year and then across many years can teach something invaluable about the meaning of life. But, for these lessons to be successful, I believe that the fruit must be sweet.

In the last issue of Martha’s Quarterly, titled Devil in Disguise, I probed questions related to identity, in particular, whether or not you needed a physical self to express and have an identity that can navigate society and possess cultural value. A song or work of art, for example, can be the proxy for an artist and evolve without the physical presence of the creator by the way it is embraced by the communities it reaches. This exploration stems from my intrigue with artificial intelligence and what these new technologies challenge in life as we know it.

This issue, Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 28, Summer 2023, Flat Juicy Round Swirl, stems from the same well of intrigue with artificial intelligence, but this time, more related to our environment and what we need to be real. Does fruit always need to be sweet? And, is the mythology of a nourishing environment more important than an environment that is thriving with bitterness and complexity?

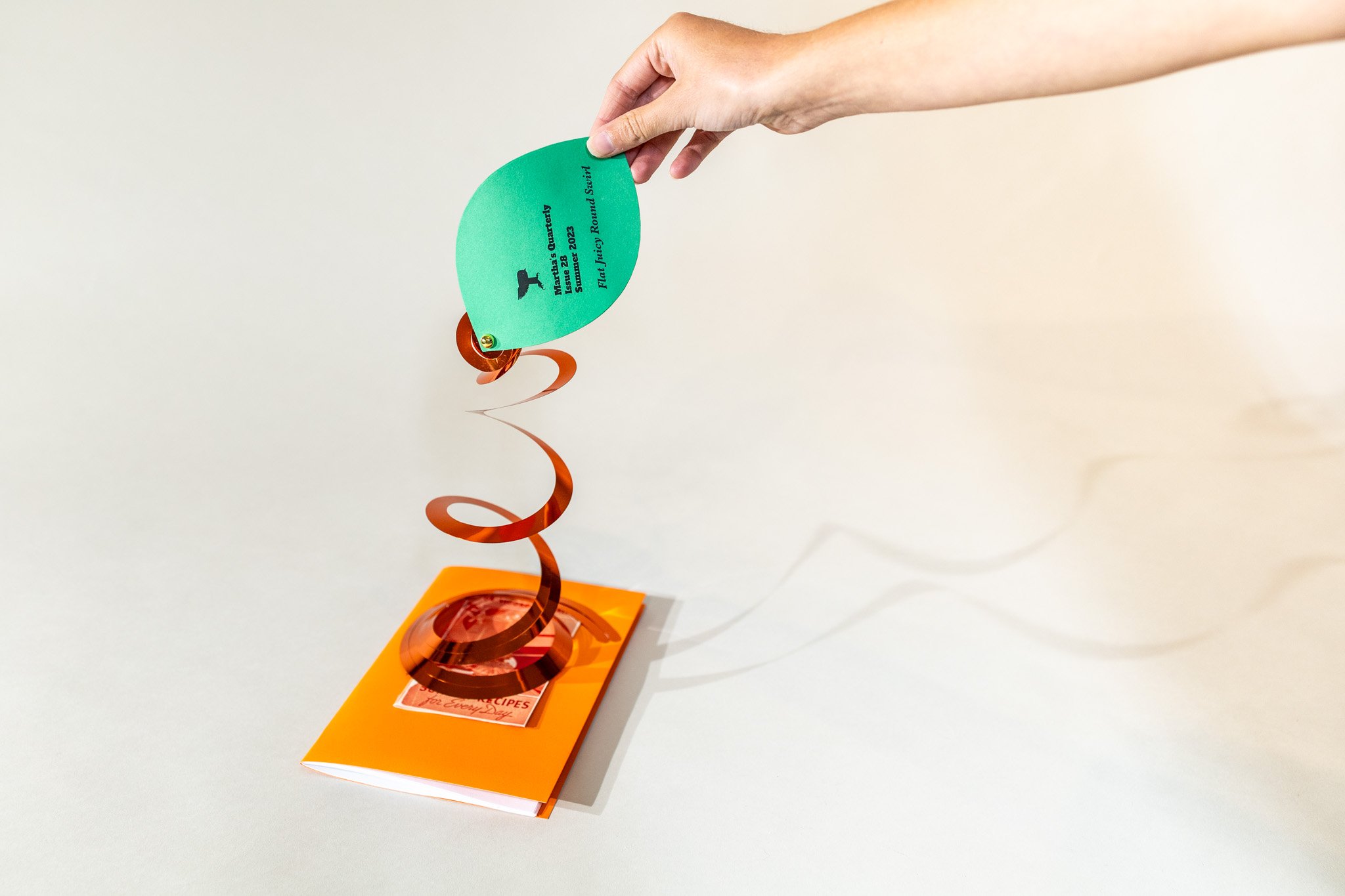

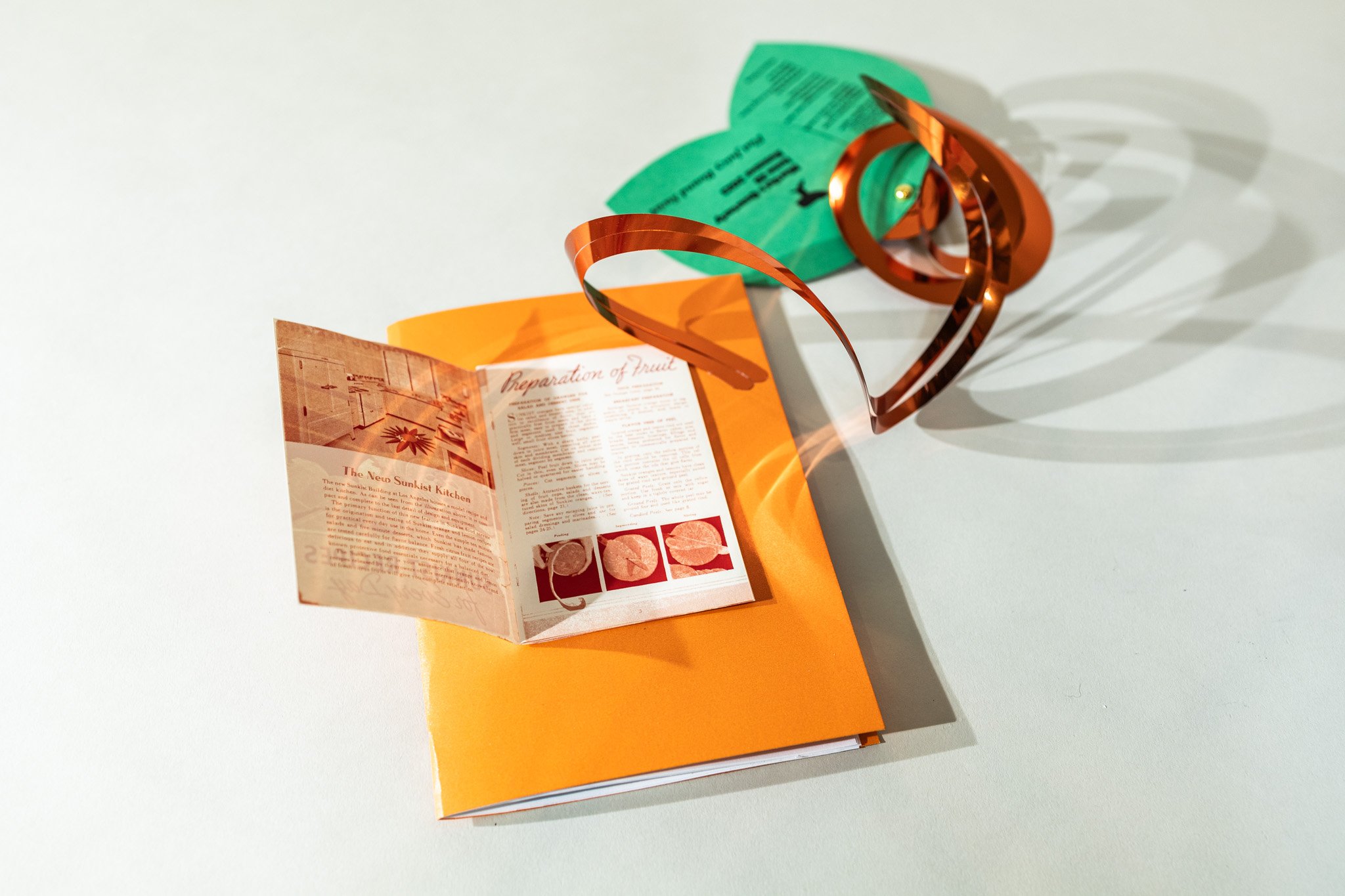

This zine begins with the image of an orange. When you turn the leaves, you’ll find a poem called “eating oranges” by Frances Chung, where she describes the several ways of eating an orange that are reflective of a culture. Here, the orange is not just fruit, but it is an expression of identity and a marker of tradition and history. Lift the leaves, and the shiny plastic materials depicting the orange splinters into a long shiny swirl that reveals a small edited vintage pamphlet published by Sunkist Oranges. The content includes recipes, a description of an idyllic kitchen that uses oranges all the time, and a story of where these perfect oranges come from– Sunkist orchards of course. The oranges in this world are guaranteed to be sweet and it is through their sweetness that they ensure the myth of health and happiness.

Today, it is not uncommon or difficult to scrutinize and criticize a company like Sunkist for being a large agricultural company that genetically modified its products for sweetness and capital gain. Genetically modified produce has been the target of many activists who blame these farming techniques for the demise of our environment, chronic illness, and much more. The sweetness elevates the mythology of the fruit. The sweetness is felt strongly on your tongue, and that is all you need to suspend your belief in its wholeness.

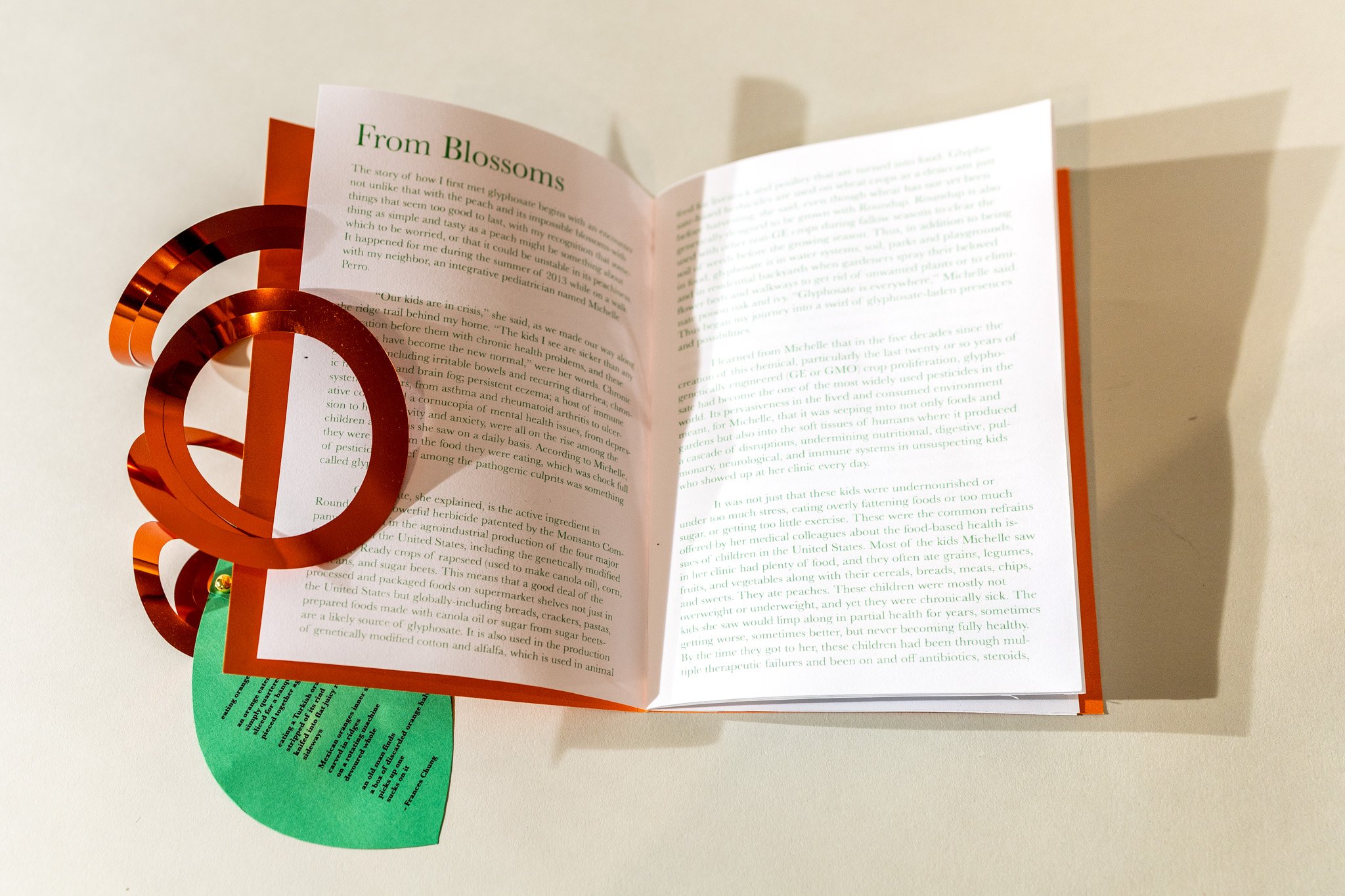

Enclosed in the larger fold of this zine are excerpts from the marvelous book Glyphosate and the Swirl by the medical anthropologist Vincanne Adams, which complicates our understanding of fruits and many other grown products by companies such as Sunkist. Her book starts with a poem too, only it is about peaches. From Blossoms by Li-Young Lee (1986) is a poem about eating peaches in the summer, the fruit’s sugar, how to eat it, and its seasonal arrival and departure summer after summer. Its “peachiness” is something that might seem too good to last, which is how Adams starts her book.

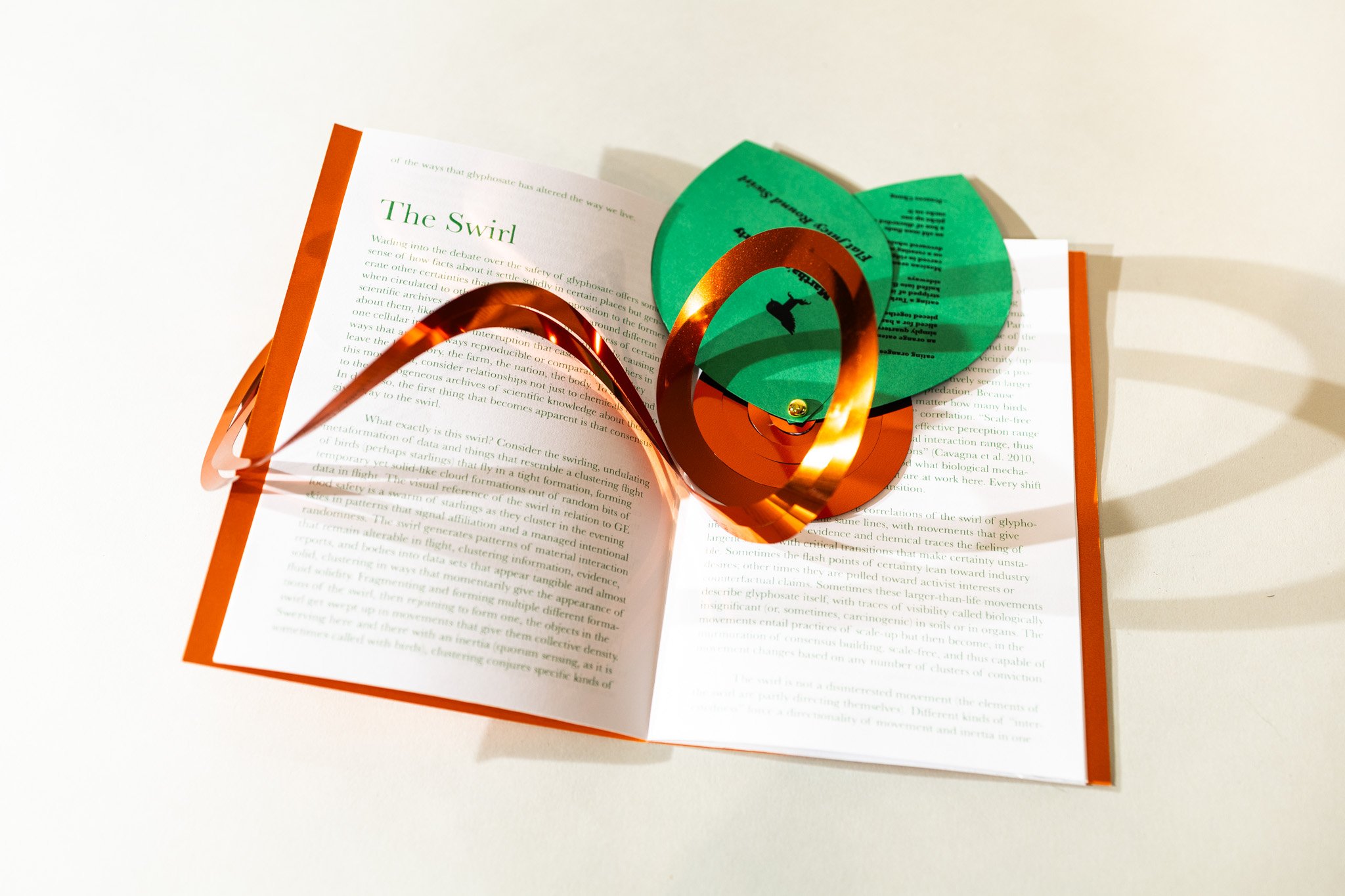

Glyphosate and the Swirl illustrates the dynamic use of glyphosate, the main active ingredient used in Roundup, the notorious herbicidal pesticide patented by Monsanto company. For this zine, Passenger Pigeon Press has included three sections of Adams’ book “From Blossoms”, “The Swirl”, and “Glyphosate Navigates the Swirl”. One of the main points of Adams’ book is demonstrating that glyphosate and its uses is an incredibly complex issue and understanding its role cannot (and should not) be summarized in neat narratives or causal effect or even right and wrong. The “From Blossoms” section describes her past project with her colleague Michelle Perro where they collaborated on the book What’s Making Our Children Sick? The book was well received, but in Adam’s hindsight, the narrative was always too perfect that it oversimplified glyphosate. The overarching narrative was that children’s health was compromised because the food they ate was poisoned with chemicals such as glyphosate leading to chronic diseases and poor gut health. This well-packaged argument made glyphosate the culprit for all of these health issues, giving academics, activists, doctors, and many other communities an identifiable villain. However, Adams felt that this narrative made issues too clear-cut and convenient for a chemical that is much more complex:

Glyphosate has come to hold larger-than-life potencies because of its histories, its many constituencies, its chemical opportunisms, and its ability to create all kinds of relationships with science, bodies, activism, and the facts. Glyphosate has many of what Eben Kirksey (2020) calls chemosocialities across environments, sensations, scientific archives, and capitalist and political opportunities. How glyphosate builds its constituencies and how clinicians learn to sense the presence of glyphosate in damaged body tissues are processes that shift our focus from abject suffering to wider questions about how we live with the chemicals that have become ubiquitous in our times. (Adams 5-6)

Vincanne Adams’ book proposes another way of thinking about glyphosate, and I find her argument compelling and inspiring. She proposes that to more deeply understand glyphosate and its issues across different constituencies, you must think of it as a “swirl”, but, more provocatively, this is not a metaphor, it is a model.

Adams’ use of the swirl concept builds from the ideas of the Italian physicist Giorgio Parisi who calls the swirling movement of a flock of starlings murmuration – “ a shape-shifting cloud, a single being moving and twisting in unpredictable formations in the sky. As if it were one swirling liquid mass.” Glyphosate’s behavior could be thought of in this way too. One characteristic of the chemical can be thought of as an evidence point– or one flying bird–, but it is still part of the whole swirl. While the narrative of glyphosate contaminating our food is true, it is still only one point of a whole moving subject. Therefore, only focusing on that narrative, or using it as part of activism or academic argument misses the totality of the issue. Adams demonstrates:

I think of the scale-free correlations of the swirl of glyphosate as working along the same lines, with movements that give individual points of evidence and chemical traces the feeling of largeness, and with critical transitions that make certainty unstable. Sometimes the flash points of certainty lean toward industry desires; other times they are pulled toward activist interests or counterfactual claims. Sometimes these larger-than-life movements describe glyphosate itself, with traces of visibility called biologically insignificant (or, sometimes, carcinogenic) in soils or in organs. The movements entail practices of scale-up but then become, in the murmuration of consensus building, scale-free, and thus capable of movement changes based on any number of clusters of conviction. (Adams 108)

I wonder if Adams’ idea of the swirl could be applied to other complexities, as a way to avoid a singular consensus on an issue and to constantly consider a topic as a complex organism in of itself. The last section that we excerpted for this zine is titled, “Glyphosate Navigates the Swirl”. In it, Adams reported on a California hearing in 2017 about the degree to which glyphosate was carcinogenic. If the chemical could be proven to be toxic at a certain level, then it would be added to a list under Proposition 65 that would mandate that the makers of Roundup must provide warning labels on any products containing it in California. Throughout the hearing, information about glyphosate behaved like a swirl:

Glyphosate took center stage, enabling its human interlocutors to speak about its potencies in their lives and in others' by calling out its multiple effects and multiple harms, culminating in one harm to rule them all: carcinogenesis. Glyphosate became the master narrator and an active participant in a political turmoil of truth claims that swirled this way and that and then settled for a moment on its potencies as a cellular mutagen. (Adams 124)

As I told you at the beginning of this introduction, I began making this quarterly while still reflecting on the subject of artificial intelligence. More broadly, I have been thinking about identity and how one’s self is presented in culture, as a real body or as a proxy. In this zine, I try to tie identity to the culture around fruit, growing fruit, consuming fruit, and our expectations around what fruit– and in general what food– needs to be. The swirl model could be applied here too because not any one of these subjects is singular, each is part of a giant flock all working together to form “identity”. The genetically modified foods made by companies such as Sunkist are so easily villainized and yet they have constructed our understanding of a sweet, perfect orange. The fruit trees I am growing will be part of my daughter’s childhood, a period in her life where her own identity will form with bitterness as much as sweetness. Consensus on one or a group’s identity misses the big picture. Aspects of an identity are all individual points of a whole, much like the murmurations of a flock of starlings.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Adams, Vincanne. “From Blossoms.” Glyphosate and the Swirl, Duke University Press, 2023, pp. 1-6.

Adams, Vincanne. “The Swirl.” Glyphosate and the Swirl, Duke University Press, 2023, pp. 106-113.

Adams, Vincanne. “Glyphosate Navigates the Swirl.” Glyphosate and the Swirl, Duke University Press, 2023, pp. 117-124.

Chung, Frances. “eating oranges.” Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple: the poems of Frances Chung, Wesleyan University Press, 2000, pp. 88.

www.passengerpigeonpress.com

@passengerpigeonpress on Instagram

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 28, Summer 2023, Flat Juice Round Swirl was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen. It was produced by Daniella Porras and Holly Greene with assistance from Chance Lockard, Lena Weiman, and Aisha Odetunde. Excerpts of text were sourced from Glyphosate and the Swirl by Vincanne Adams with permission from Duke University Press and Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple by Frances Chung with permission from Wesleyan University Press, as cited below. The Sunkist Oranges booklet is a vintage publication. Flat Juicy Round Swirl was made using an orange party decoration, green, white, and ivory textweight paper, and metallic orange cardstock. Everything was printed with a photocopier. Baskerville font was used in various styles and sizes throughout.

Published in September 2023, this is an edition of 250.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 27

Spring 2023

Devil in Disguise

8.75” x 6”

About the contributors:

Tommy Kha is a Chinese-Vietnamese American photographer, working between New York City and Memphis, Tennessee. He likes to think he takes after his great aunt, who “read too many books and went crazy.”

Karl Fredric MacDorman is Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at Indiana University’s Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering. He was previously an Assistant Professor at Osaka University’s School of Engineering. He received his Ph.D. in Computer Science from Cambridge University in 1997 and his B.S. in Computer Science from the University of California at Berkeley in 1988. He has published over 100 papers on human–robot interaction, machine learning, and cognitive science. His main research interests include the emergence and grounding of symbols, cognitive development robotics, android science, and the uncanny valley.

Masahiro Mori is Professor Emeritus at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, where he led robotics research for nearly two decades. He is also President of the Mukta Institute and Honorary President of the Robotics Society of Japan. Mori completed his doctorate in engineering at the University of Tokyo and has served on their faculty, among others. Mori is widely celebrated for introducing the concept of the uncanny valley in 1970, which has influenced fields ranging from humanoid robotics and computer animation to perceptual psychology and cognitive neuroscience. He is known for his thoughts on robotics and Buddhism, as detailed in The Buddha in the Robot and in many other books. He has contributed greatly to robotics and automation research and education, founding some of the earliest robotics contests. He has won numerous awards from learned societies, the NHK Broadcasting Culture Award in 1992, the Medal of Honor in 1994, and the Order of the Rising Sun in 1999.

One of my favorite occurrences in Spring is the arrival of daffodils. As soon as the temperatures rise just enough, it seems as though they explode out of the ground. Bursts of yellow, white, and orange line parts of roads and highways; they cover hills like a blanket, and circle around ponds and lakes. The daffodil is also known as the Narcissus flower after the story of Narcissus who fell to his demise by being absorbed into a pond and coming back as this flower each Spring of the year.

How we are represented has been a hot and provocative subject over the last decade. This conversation continues to evolve in controversial ways and the other story of this Spring related to representation was the debut of Chat GPT 4, an artificial intelligence chatbot developed by OpenAI that can generate large pieces of language very similar to human speech. Chat GPT 4 can mime human language so well that you can ask it (as my husband did) to write poems in the style of Jack Kerouac, create artist statements (as I saw on Instagram), and much more. It impressively writes faster than most humans and poses a new, palpable existential threat to the meaning of being a human.

A few weeks after the launch and wide use of Chat GPT 4, over 1,000 tech leaders and researchers including Elon Musk urged artificial intelligence labs to, “immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4.” (1) The letter illustrated that:

Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth, and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources. Unfortunately, this level of planning and management is not happening, even though recent months have seen AI labs locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one – not even their creators – can understand, predict, or reliably control. (2)

In his recent interview with Tucker Carlson, Elon Musk emphasized these points by stating, "AI is more dangerous than, say, mismanaged aircraft design or production maintenance or bad car production in the sense that it has the potential, however small one may regard that probability, but it is not trivial; it has the potential of civilizational destruction.” (3) These ominous warnings put into question the meaning of human creation and our relationships. It challenges what is real or fake and whether that distinction is important at all.

But, in another recent interview with Manolis Kellis, a professor of Computer Science at MIT on the Lex Fridman podcast, Professor Kellis illustrates the integration of AI into our ordinary lives from a human evolution perspective. Considering AI as another step forward in our evolution he explains:

But maybe the next round of evolution on Earth is self-replicating AI, where we're actually using our current smarts to build better programming languages and the programming languages to build, chat GPT and that then build the next layer of software that will then sort of help AI speed up. And it's lovely that we're coexisting with this AI that sort of the creators of this next layer of evolution and this next stage are still around to help guide it and hopefully will be for the rest of eternity as partners. But it's also nice to think about it as simply the next stage of evolution where you've kind of extracted away the biological needs. Like if you look at animals, most of them spend 80% of their waking hours hunting for food or building shelter. Humans, maybe 1% of that time. And then the rest is left to creative endeavors. And AI doesn't have to worry about shelter, et cetera. So basically it's all living in the cognitive space. So in a way it might just be a very natural sort of next step to think about evolution. (4)

In other words, the physical world as we know it will change and become non-essential. Tom Hanks really illustrated this concept in this comment on the Adam Buxton podcast, “Anybody can now recreate themselves at any age they are by way of AI or deep fake technology … I could be hit by a bus tomorrow and that’s it, but my performances can go on and on and on”. (5)

All of this is the context for this Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 27, Spring 2023, Devil in Disguise, a title that takes after Elvis Presley’s 1968 hit (You’re the) Devil in Disguise. In the jolly tune, the lyrics warn:

You look like an angel (look like an angel)

Walk like an angel (walk like an angel)

Talk like an angel

But I got wise

You're the devil in disguise

Oh, yes, you are, devil in disguise

Humor the devil in disguise to be AI and that Elvis’ image has been one of the most desirable acts to preserve and keep alive in culture. There are countless Elvis impersonators who officiate weddings, sing, and dance. Sometimes these talents are so similar to the original Elvis that the audience can easily suspend their imagination into the act and imagine the King as still being alive. But, as AI becomes more common and integrated into daily life, it will be no surprise when AI can actually become Elvis.

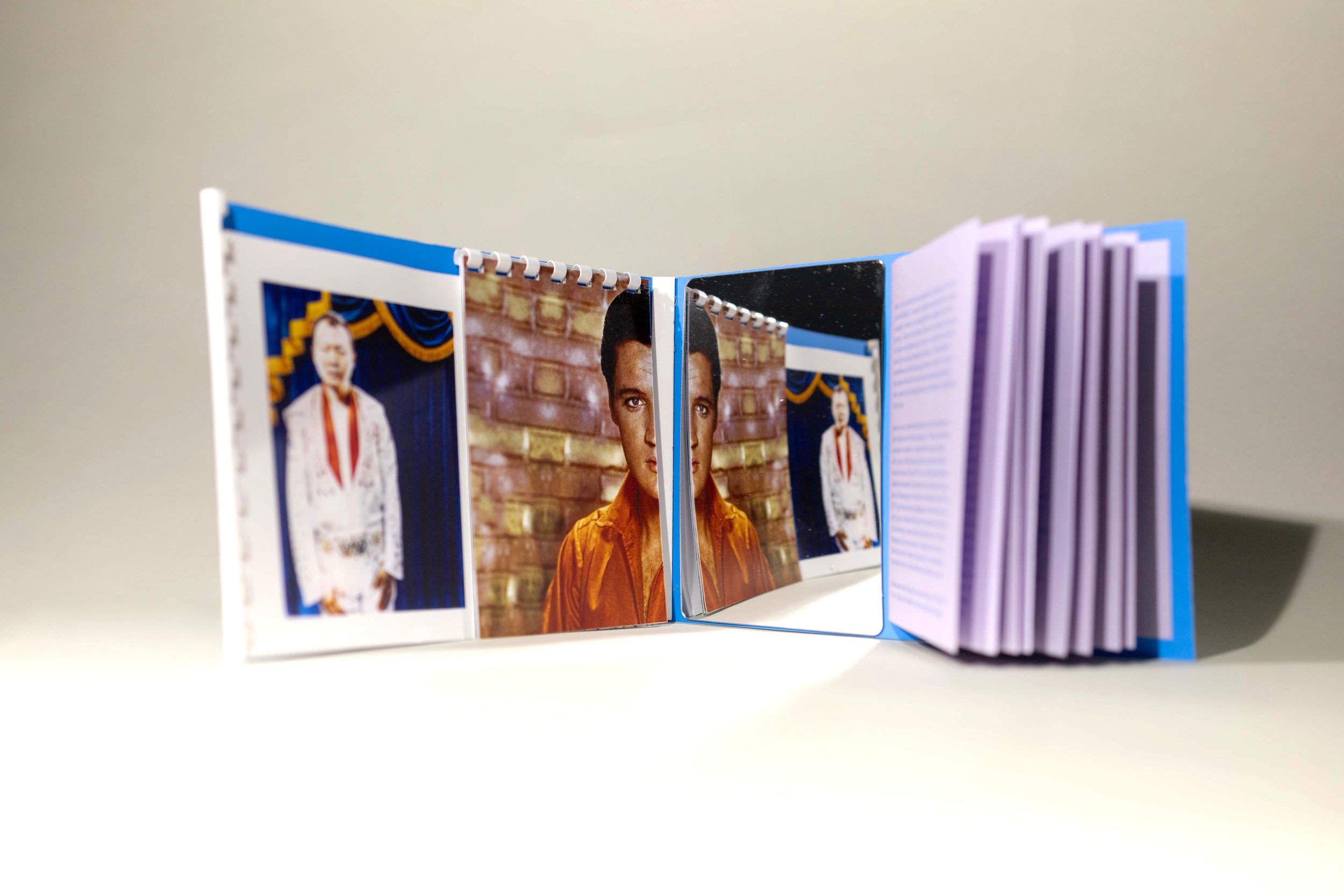

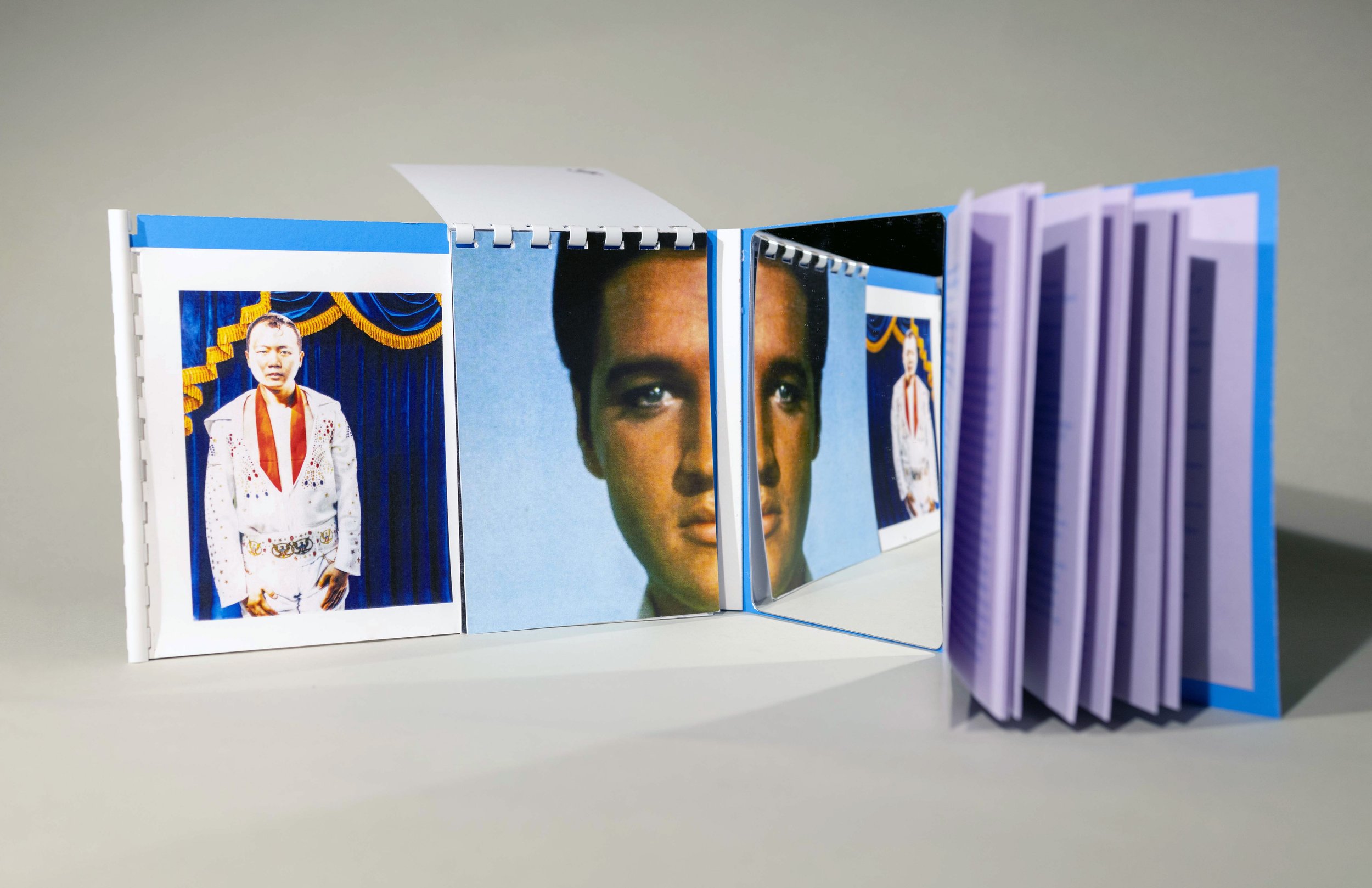

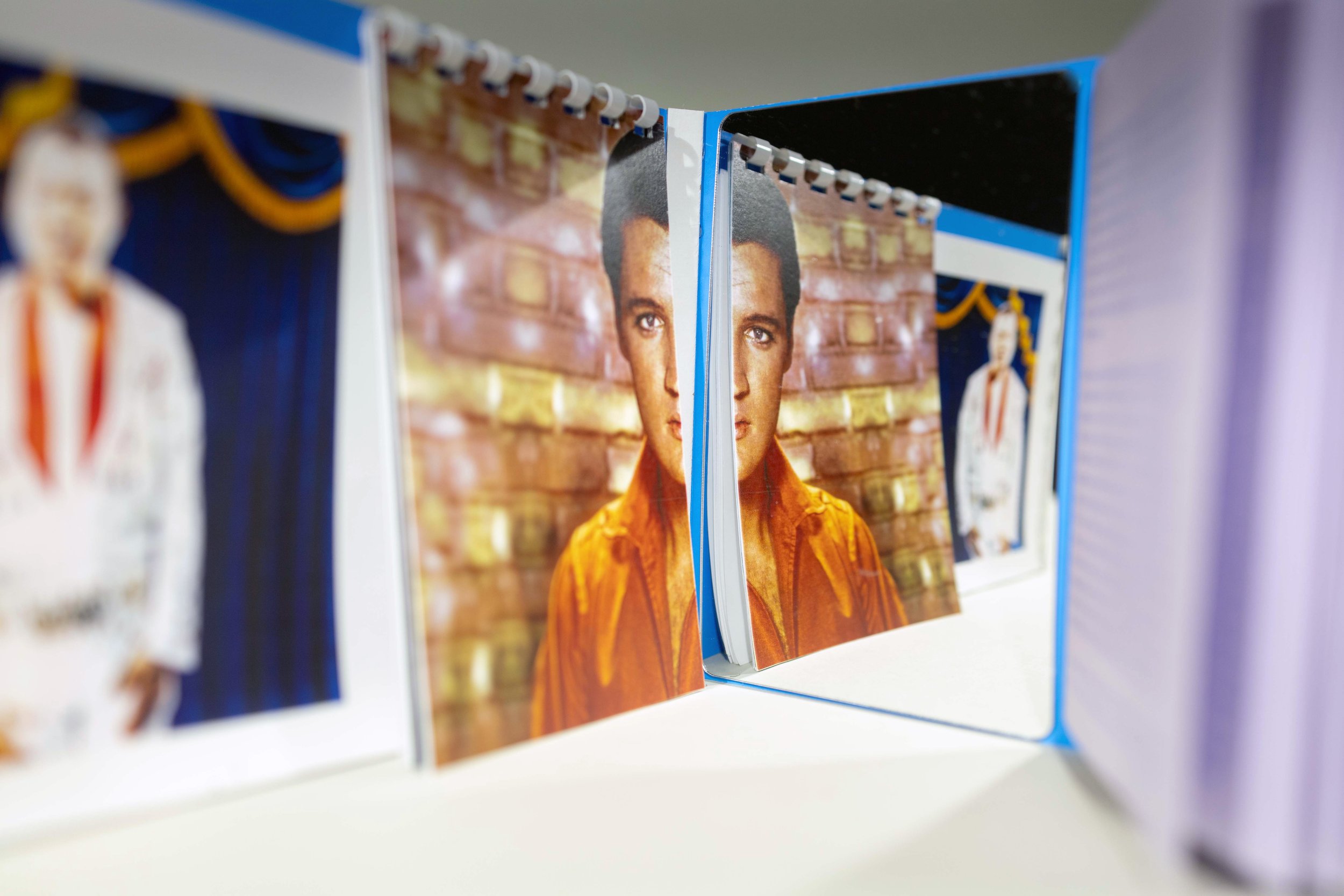

Consider the blurring of real and fake Elvis as you open this Martha’s Quarterly. To the left of the centerfold is a series of half portraits of Elvis. To the right is a mirror that allows you to reflect the half face on the left, rendering the illusion of a whole face. Sometimes they look acceptable, but at other times, the symmetry appears so perfect that the portrait looks “wrong”.

This sensation and its possible relevance to AI is why we are featuring the 1970 essay The Valley of the Uncanny by Masahiro Mori who was a professor of robotics at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The essay first appeared in a little-known Japanese journal called Energy. While it received very little attention in the first few years after its publication, it is now a very important article in the fields of robotics and culture. One of the main points of Mori’s essay is a description of a space where human creations of proxies such as prosthetics can be so similar, almost exacting of humanness, that the object evokes a feeling of eeriness or creepiness. Contrarily, human creations of puppets or personified toys, do not evoke this uneasy feeling. This space is the Valley of the Uncanny, and I wanted to center this concept within the conversation of AI.

Towards the end of Mori’s essay, he probes at essential questions on human existence:

I think this descent explains the secret lying deep beneath the uncanny valley. Why were we equipped with this eerie sensation? Is it essential for human beings? I have not yet considered these questions deeply, but I have no doubt it is an integral part of our instinct for self-preservation. (6)

This is the same question that I would also ask of AI, especially as it becomes ever-present in ordinary life. I wonder if human societies can actually embrace Kellis’ suggestion that AI is part of our natural evolution. Or, is AI to be extremely restricted because it is existential? These are the looming questions that I am asking as this issue of Martha’s Quarterly also presents a selection of pictures by the artist Tommy Kha.

In his portfolio, Kha is costumed as Elvis, reproduced as a cardboard printout, and sometimes only represented as a shadow. These pictures explore Kha’s identity in a host of ways, sometimes, with his mother who could be a reflection of the artist as she sits by him or with her own face cut out. The poetics of Kha’s images are expansive but I can also ground them in the underlying questions of this issue. What is our identity when we live in a form outside of our own flesh and bones? What is human life or dignity when we are physically detached from it? Can our environment and the people we know be enough to stand in for our own form? And if our lives can be extended through AI, then at which point will we no longer be necessary?

This issue of Martha’s Quarterly will probably arrive in your mailbox in the last days of Spring and the heat of Summer burns across my garden, where the daffodils of Spring now look shriveled and brown. Narcissus fell to his demise because he saw a reflection of himself in a pool and fell in love with it. Death came not in what he saw but in what the reflection could not do. The reflection could not love Narcissus, because in the end, it was not a real person who could reciprocate the same passion back.

-Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

https://www.foxnews.com/media/elon-musk-develop-truthgpt-warns-civilizational-destruction-ai

https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/16/entertainment/tom-hanks-ai-movies-scli-intl/index.html

Mori, Masahiro. “The Uncanny Valley.” Translated by Karl Fredric MacDorman. Energy, 1970.

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 27, Spring 2023, Devil in Disguise was edited by Tammy Nguyen, designed and produced by Holly Greene with assistance from Daniella Porras and Jane Lillard. The images of Elvis were sourced from Encyclopedia Britannica. Devil in Disguise was produced using full-color photocopy, silkscreen printing, hot stamping, mirrors, and comb bindings. The cover paper is 100lbs text weight, and the internal paper is 20 lbs, 32 lbs, and 100 lbs text weight. The fonts used are Cambria, Alfa Slab, and Univers.

Published June 2023, this is an edition of 200.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 26

Winter 2023

Tigididada

7.25” x 5.75”

About the contributors:

Paolo Javier's produced three albums of sound poetry with Listening Center (David Mason), including the limited edition pamphlet/ cassette Ur’lyeh/ Aklopolis (Texte Und Tone) and the booklet/cassette Maybe the Sweet Honey Pours (Nion Editions/Temporary Tapes). A featured artist in Greater New York 2015 and in Queens International 2018: Volumes, he is the recent author of a book of paraliterary and hybrid poems, True Account of Talking to the 7 in Sunnyside (Roof Books).

Mark Thomas Gibson’s (b. 1980, Miami, FL) work explores through painting and drawing an America where every viewer is implicated as a potential character in the story of the country's unfurling history. Gibson is a recent recipient of a 2021-2022 Hodder Fellowship, A 2021 Pew Grant and a 2022-2023 Guggenheim Fellowship.

In these last few weeks of winter, snow has finally arrived in Connecticut, where I live. Over the last few months, many people–including myself–have talked about how strange this winter has been. The farmer who lives next to me posted a funny picture of spring flowers emerging from the ground in January; at my local coffee shop, I’ve heard people chit chat about how they miss the snow; mothers in my life have talked about how their kids just want a snow day. My region has not been the only one that has been deprived of snow: different newspapers have reported the lack of snow in the Swiss Alps with a picture of a strip of snow down a grassy mountain. Meanwhile, people from places that typically do not have a lot of snowfall have been posting on social media about the extraordinary amounts of snow they have received. I saw pictures from Northern California with houses covered in white. It was snowing in LA, and others were snowed in in Utah.

I am introducing Martha’s Quarterly, Winter 2023, Issue 26, Tigididada, with a description of this bizarre winter weather because weather has been a subject in my life that has oscillated between the spaces of small talk and big, serious talk. The weather, something that all humans experience everyday, is a subject that can be a trivial conversation, but in the context of climate change, it can also be the subject of grave urgency, not to be taken lightly. I am interested in the malleable nature of this subject and, more broadly, how any subject can simultaneously be a part of both daily small talk and newspaper headlines.

Since the integration of social media in our daily lives, we have witnessed small talk in “internet-town-squares” such as Twitter and Facebook go viral–with consequences. For example, in 2010, Paul Chambers, who was simply flying from Dorcaster, England to Northern Ireland, got so frustrated when a snowstorm delayed his flight that he tweeted, “Crap! Robin Hood Airport is closed. You’ve got a week to get your shit together, otherwise I’m blowing the airport sky high!” This joke was interpreted as a threat, and Mr. Chambers was interrogated for eight hours, fined, and ultimately lost his job. (1)

Small talk and jokes such as this are part of normal social life. How someone talks and the tone in which they express themselves are dynamic mechanisms of communication and expression that contextualize words. Additionally, words can also take on unique specificity depending on their context, whether it is the historical time in which they are uttered or the local culture in which they are shared. These gestures, when displaced from their original context and placed into a virtual reality such as Twitter, become vulnerable to disconnected interpretations that can and have led to confusing consequences in real life.

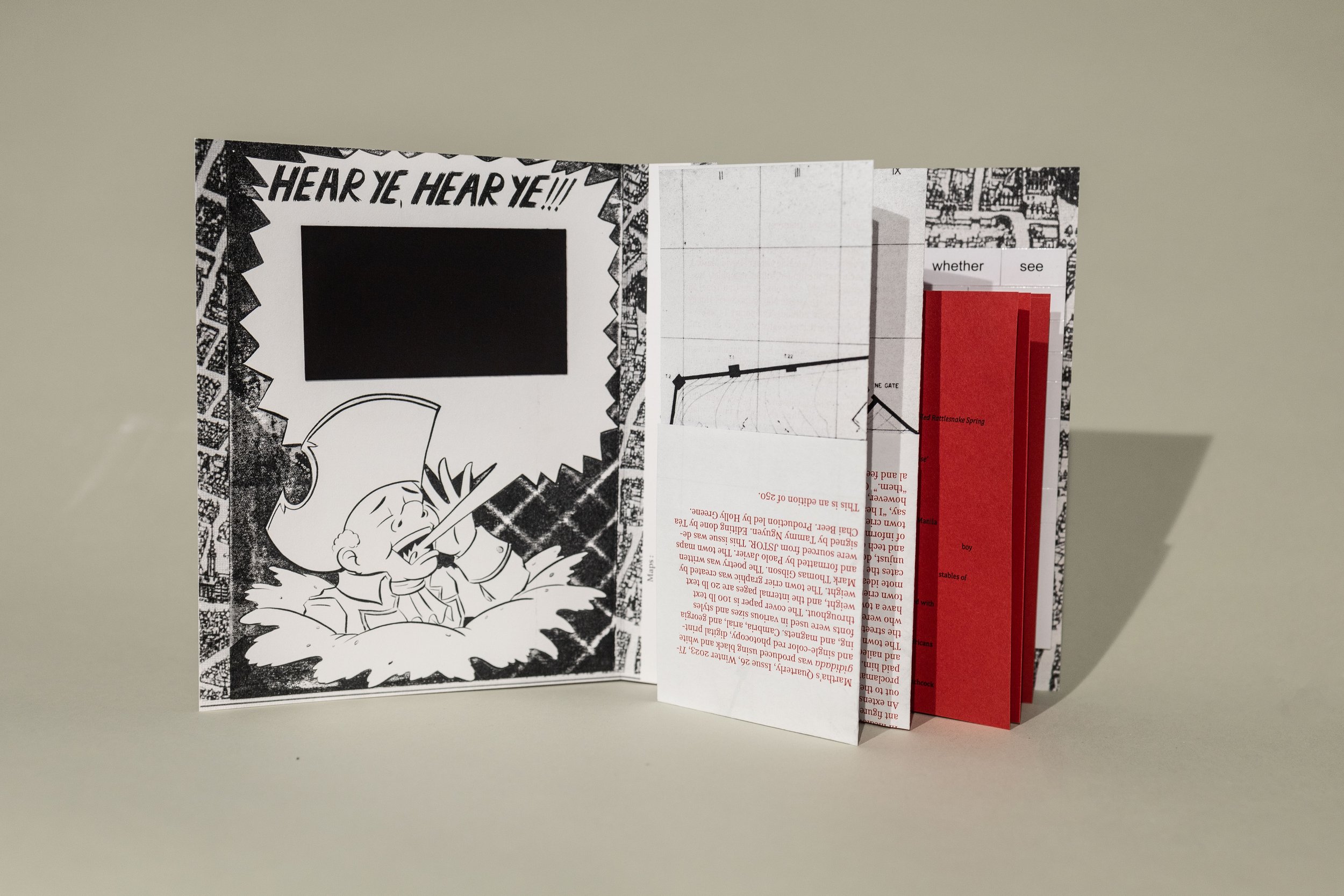

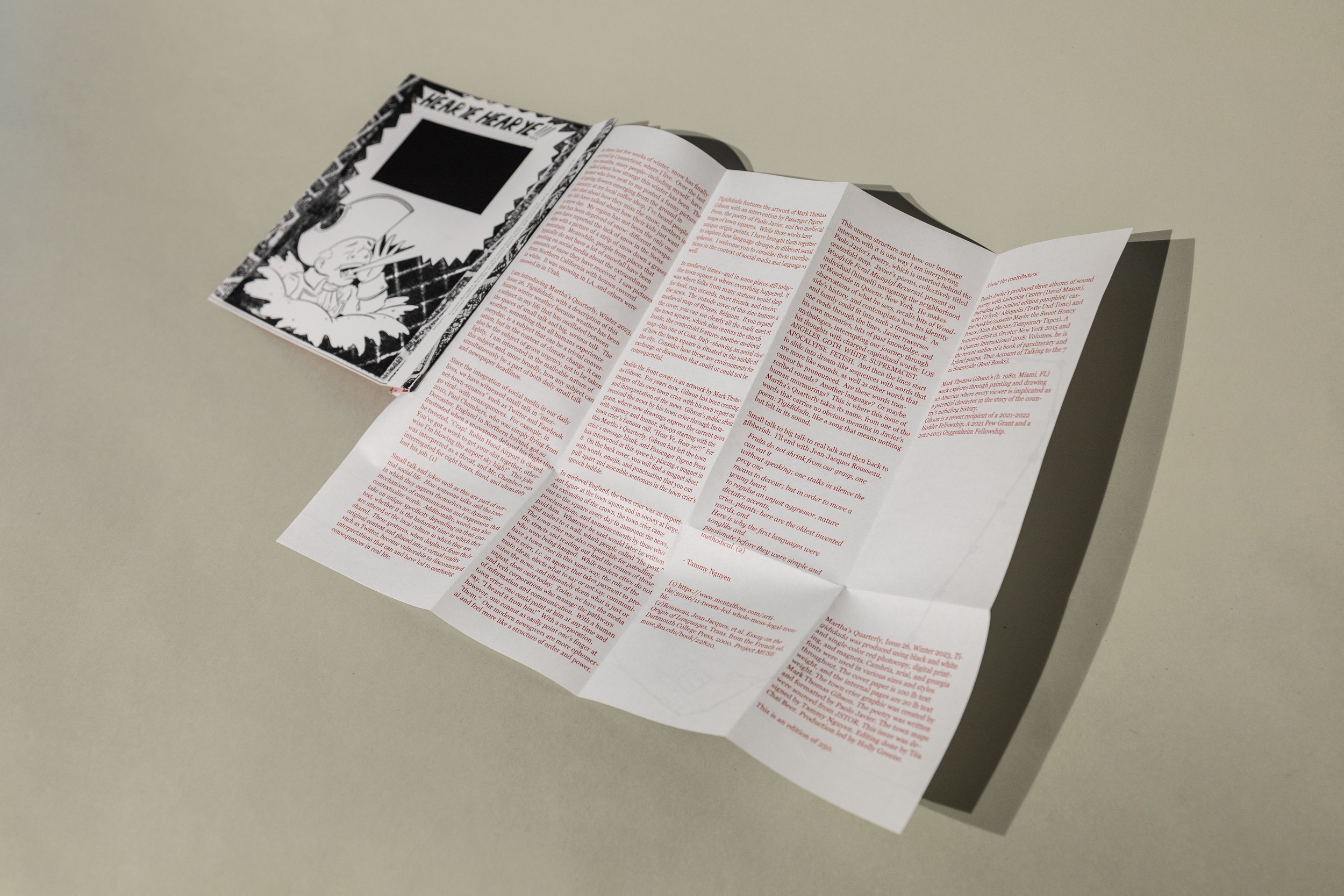

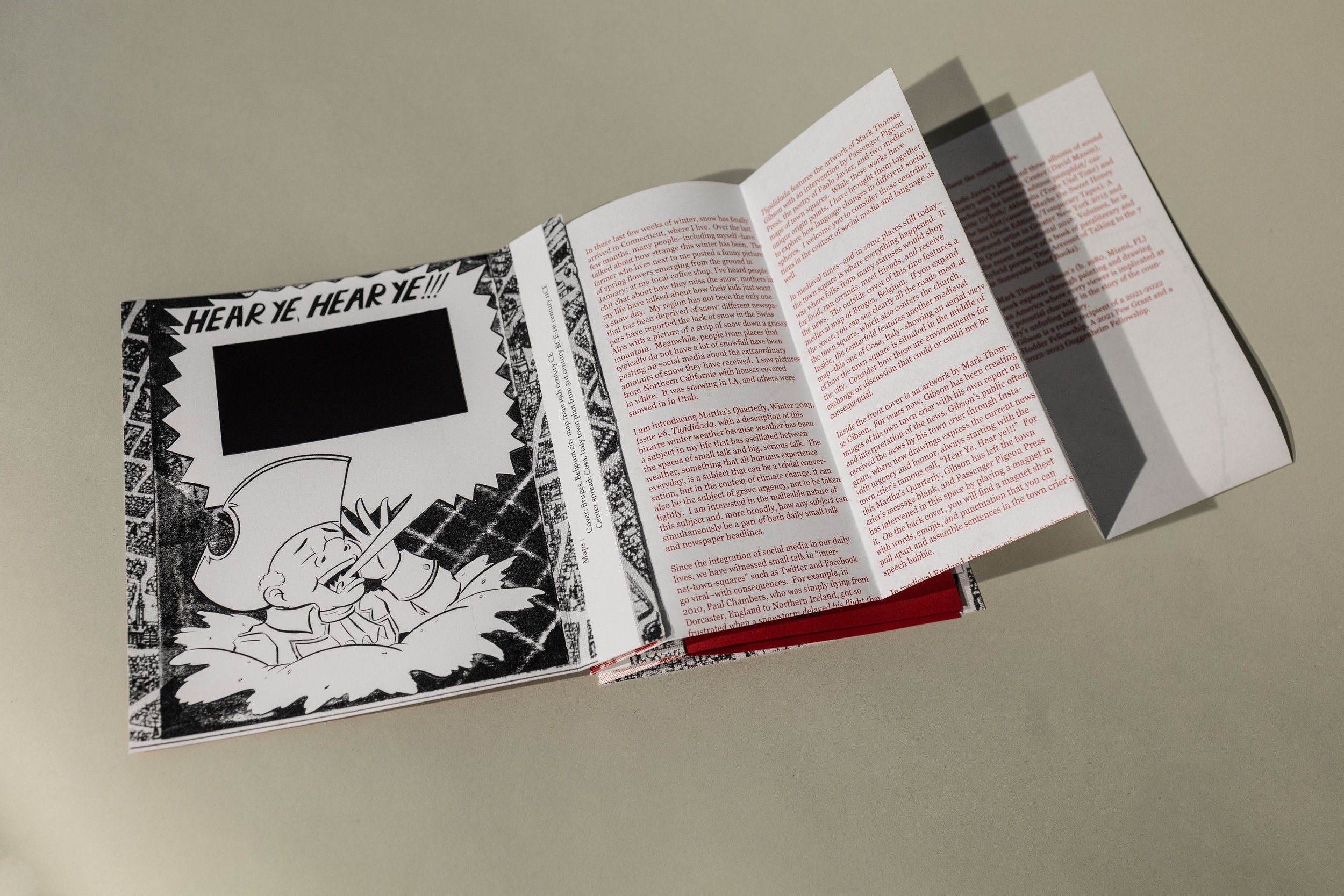

Tigididada features the artwork of Mark Thomas Gibson with an intervention by Passenger Pigeon Press, the poetry of Paolo Javier, and two medieval maps of town squares. While these works have unique origin points, I have brought them together to explore how language changes in different social spheres. I welcome you to consider these contributions in the context of social media and language as well.

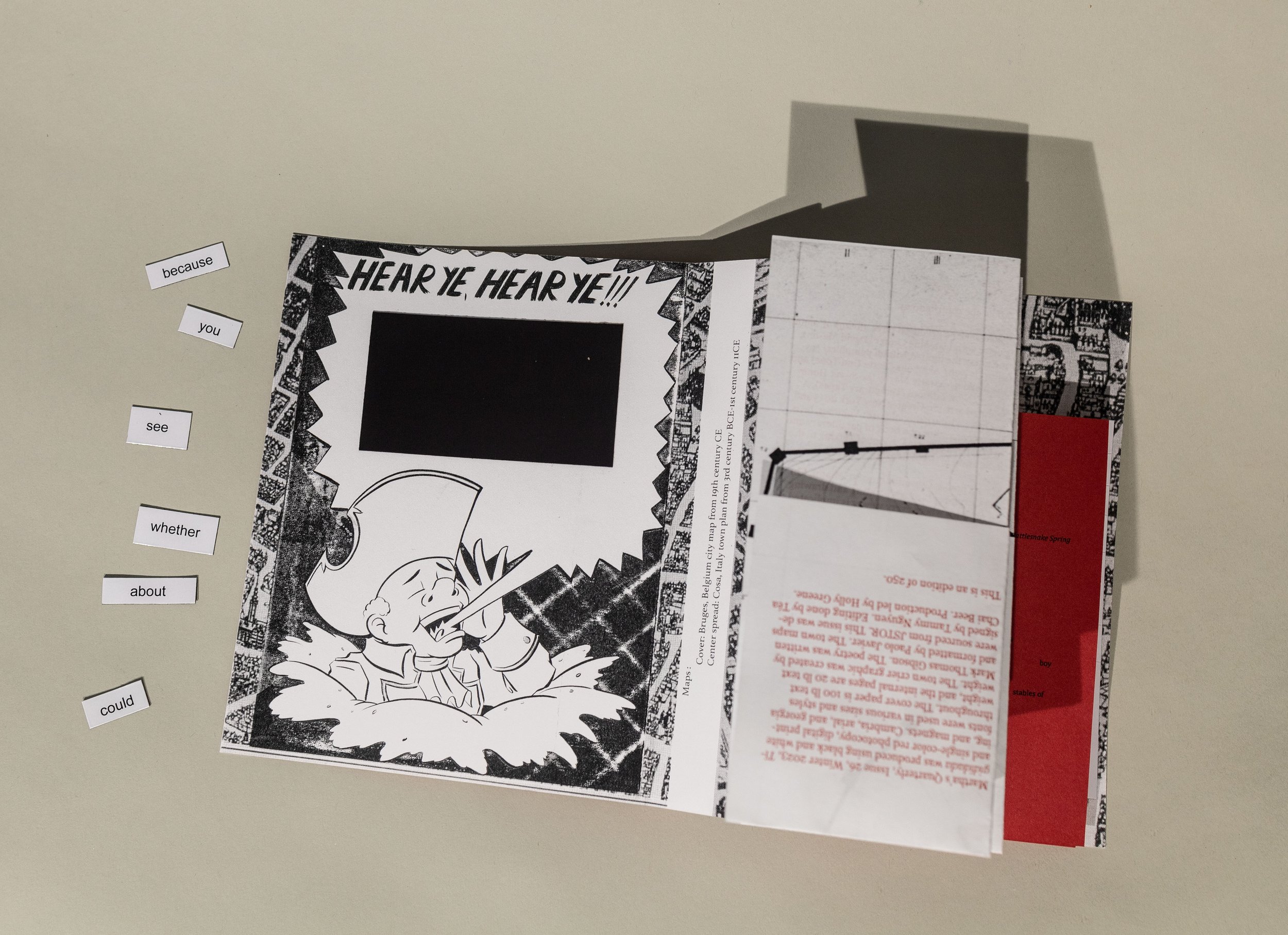

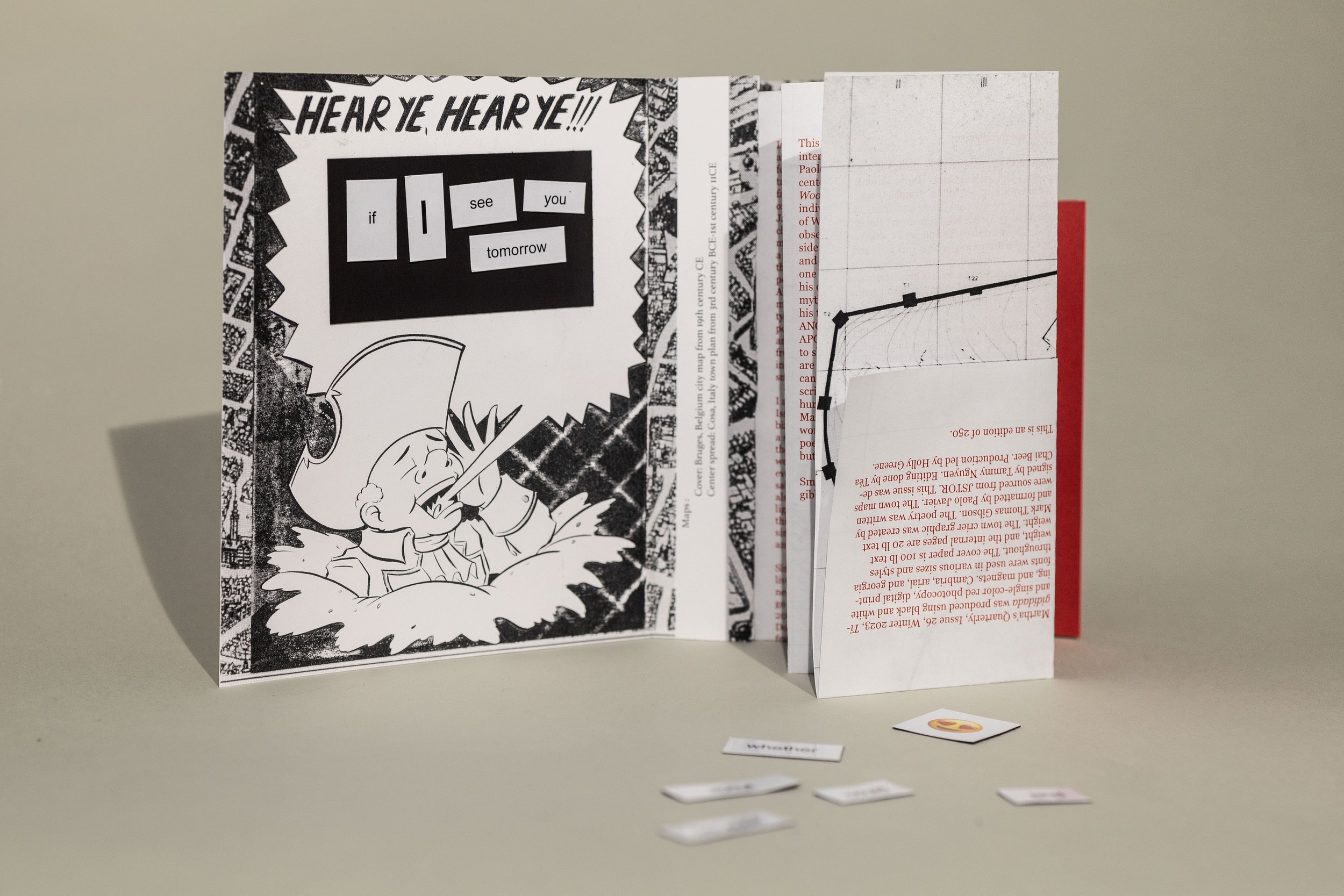

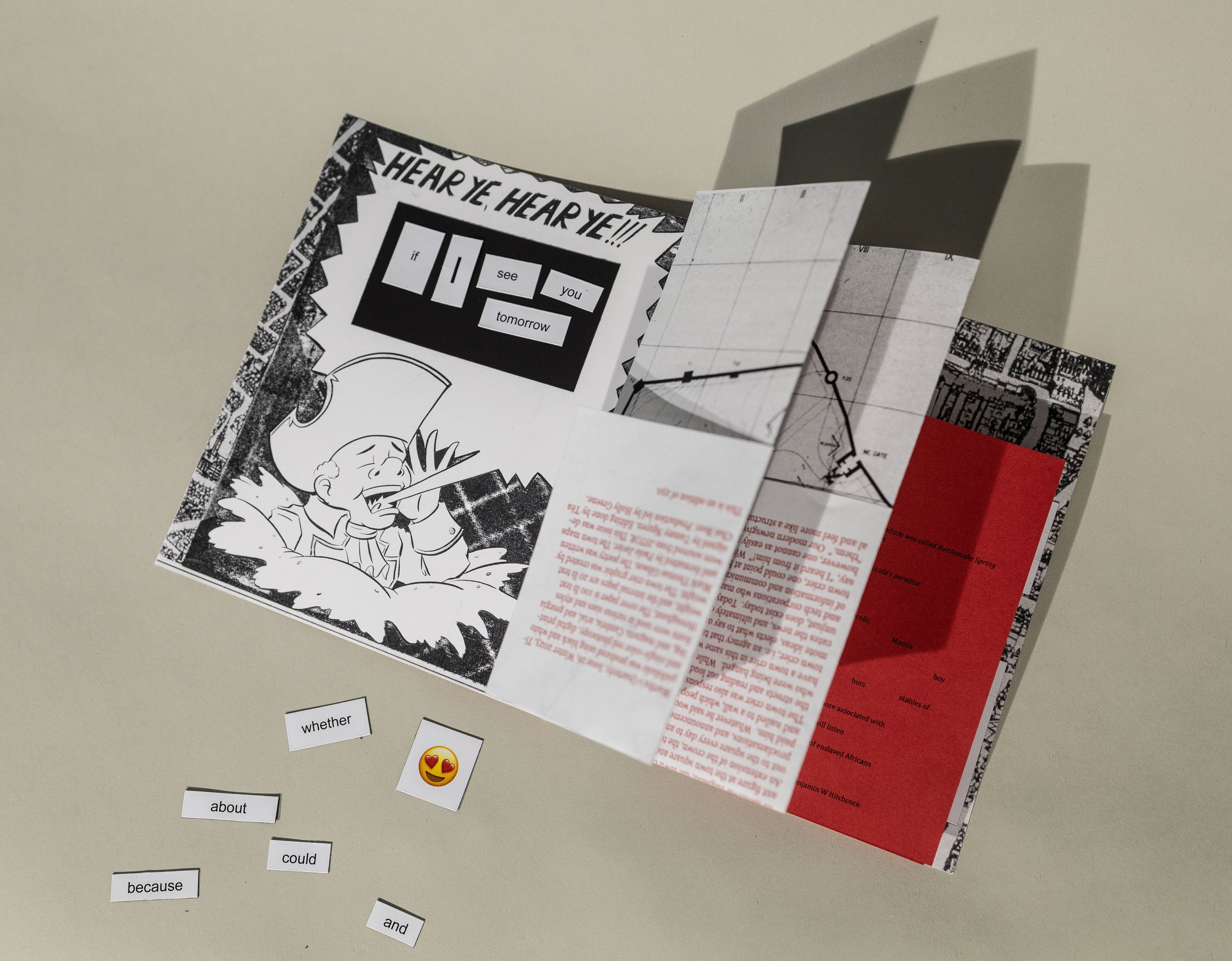

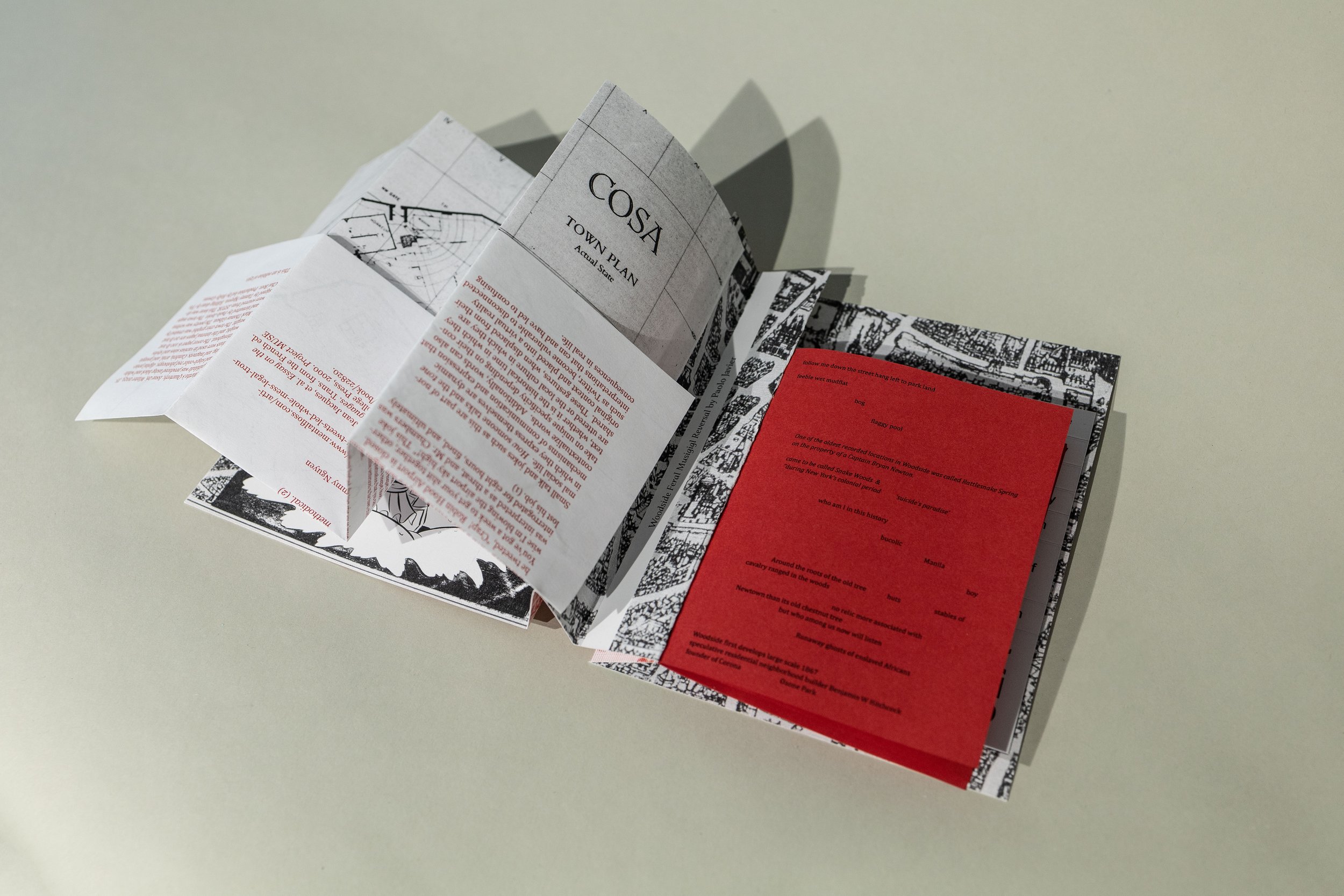

In medieval times–and in some places still today–the town square is where everything happened. It was where folks from many statuses would shop for food, run errands, meet friends, and receive the news. The outside cover of this zine features a medieval map of Bruges, Belgium. If you expand the cover, you can see clearly all the roads meet at the town square, which also centers the church. Inside, the centerfold features another medieval map–this one of Cosa, Italy–showing an aerial view of how the town square is situated in the middle of the city. Consider how these are environments for exchange or discussion that could or could not be consequential.

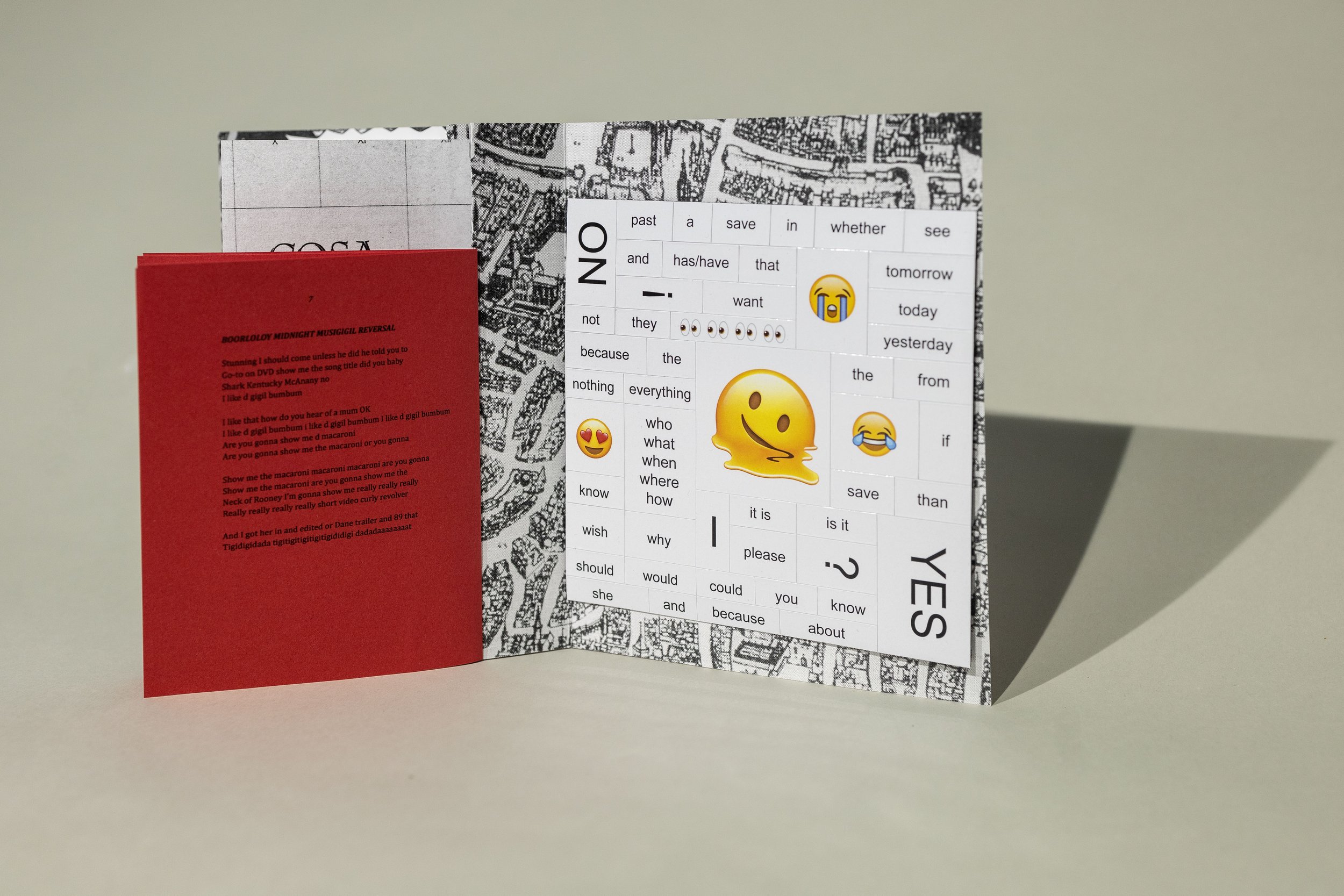

Inside the front cover is an artwork by Mark Thomas Gibson. For years now, Gibson has been creating images of his own town crier with his own report on and interpretation of the news. Gibson’s public often received the news by his town crier through Instagram, where new drawings express the current news with urgency and humor, always starting with the town crier’s famous call, “Hear Ye, Hear ye!!!” For this Martha’s Quarterly, Gibson has left the town crier’s message blank, and Passenger Pigeon Press has intervened in this space by placing a magnet in it. On the back cover, you will find a magnet sheet with words, emojis, and punctuation that you can pull apart and assemble sentences in the town crier’s speech bubble.

In medieval England, the town crier was an important figure at the town square and in society at large. An extension of the crown, the town crier came out to the square every day to announce the news, proclamations, and announcements by those who paid him. Whatever he said would later be written and nailed to a wall, which people called “the post.” The town crier was also responsible for patrolling the streets and reading out loud the crimes of those who were being hanged. While modern cities do not have a town crier in this same way, the role of the town crier, i.e. an agency that takes payment to promote ideas, elects what to say or not say, communicates the news, and ultimately deem what is just or unjust, does exist today. Today, we have the media and tech corporations who manage the pathways of information and communication. With a human town crier, one could point at him at any time and say, “I heard it from him!” With a corporation, however, one cannot as easily point one’s finger at “them.” Our modern newsgivers are more ephemeral and feel more like a structure of order and power.

This unseen structure and how our language interacts with it is one way I am interpreting Paolo Javier’s poetry, which is inserted behind the centerfold map. Javier’s poems, collectively titled Woodside Feral Musigigl Reversal, present an individual (himself) navigating the neighborhood of Woodside in Queens, New York. He makes observations of what he sees, recalls bits of Woodside’s history, and contemplates how his identity and family could fit into such a framework. As one reads through the lines, Javier traverses his own memories, bits of past knowledge, and mythologies, interrupting our journey through his thoughts with charged capitalized words: LOS ANGELES. GOTH. WHITE. SUPREMACIST. APOCALYPSE. FETISH. And then the lines start to slide into dream-like sequences with words that are more like sounds, as well as other words that cannot be pronounced. Are these words transcribed sounds? Another language? Or maybe human murmurings? This is where this issue of Martha’s Quarterly takes its name, from one of the words that carries no obvious meaning in Javier’s poem: Tigididada, like a song that means nothing but felt in its sound.

Small talk to big talk to real talk and then back to gibberish. I’ll end with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whom Javier also quotes:

Fruits do not shrink from our grasp, one can eat it

without speaking; one stalks in silence the prey one

means to devour; but in order to move a young heart,

to repulse an unjust aggressor, nature dictates accents,

cries, plaints: here are the oldest invented words, and

Here is why the first languages were songlike and

passionate before they were simple and methodical. (2)

- Tammy Nguyen

(1) https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/30196/11-tweets-led-whole-mess-legal-trouble

(2) Rousseau, Jean Jacques, et al. Essay on the Origin of Languages. Trans. from the French ed. Dartmouth College Press, 2000. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/22820.

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 26, Winter 2023, Tigididada was produced using black and white and single-color red photocopy, digital printing, and magnets. Cambria, arial, and georgia fonts were used in various sizes and styles throughout. The cover paper is 100 lb text weight, and the internal pages are 20 lb text weight. The town crier graphic was created by Mark Thomas Gibson. The poetry was written and formatted by Paolo Javier. The town maps were sourced from JSTOR. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen with additional editing from Téa Chai Beer. Production was led by Holly Greene with assistance from Catherine Capeci, Chance Lockard, Sophie Clapacs, Minyoung Huh, Lena Weiman, Alex Weidenfeld, Rebecca Trevino, and Jane Lillard.

Publish March 2023, this is an edition of 250.