MQ 2019

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 14

Winter 2019

BODY HEAT

6.5” x 5.25”

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 14, Winter 2019, Body Heat

About the contributors:

Nicholas Cerone is the co-founder of Raise the Bar Fitness, a personal training facility in the Sunset District of San Francisco. He supports a whole foods diet.

Drea Cofield grew up in a small town in Indiana. She earned an MFA in Painting from Yale in 2013 and has been living and working in Brooklyn ever since.

Irene Gardner is a registered dietitian, specialist in sports dietetics, and personal trainer at IG Nutrition & Performance based in San Francisco, CA.

Eban Goodstein is an economist and public educator who directs the Center for Environmental Policy and the MBA in Sustainability program at Bard College in New York.

Here are a few things that I understand about how I can eat in a way that helps the climate crisis. I know that I should drastically limit my consumption of meat and dairy, because many of those production methods require an exuberant use of fossil fuel and energy to produce. I should eat mostly vegetables that are seasonal and local: it’s good for my body, and if it has come from a closer location to where I live and produced in a smaller quantity with a slower method, it likely consumed less human and fossil fuel-based energy. I know that not all plant-based things are made equal: almond milk, for example, takes an incredible amount of energy to produce, and much of it is produced industrially. Low-level fish such as sardines and anchovies are good to eat, because they reproduce quickly and cost relatively low amounts of energy to get to our table. Oysters and seaweed are also good, because by eating them I support ocean farming, and shellfish and seaweed in particular contribute to detoxifying the ocean. But not all seafood is made equal: tuna, for example, requires an incredible amount of energy to produce and ought to be enjoyed rarely; on the other hand, wild Alaksan salmon produced by the Indigenous people of Bristol Bay, Alaska is very good to eat because their business is at risk of being taken over by pebble mining, and they keep one of the most sustainable and clean fisheries in the world. (1)

For a few months now, I have been following this diet. I have been learning about my food, where it comes from, especially what it took to produce, and how to create delicious and balanced meals in terms of flavor and nutrition to contribute to a sustainable lifestyle and planet. And, I feel good.

However, what remains abstract to me is the power of the collective and how my individual efforts can be felt on a mass scale, enough so that there is more visible action on a policy and industrial level to mitigate climate change. Politicians and other media spokespeople have used the talking point “2 degrees” on many occasions: if the planet goes up “2 degrees,” if we can keep the temperature down and avoid “2 degrees...” I could tell you that I had heard it, but I could not explain to you exactly what was being said nor what I totally understood. What I did take away, though, was that something about the rise in temperature would lead to humanity’s demise; still, there is a fog of confusion in terms of how to understand what exactly is happening to our planet in a clear and visceral way.

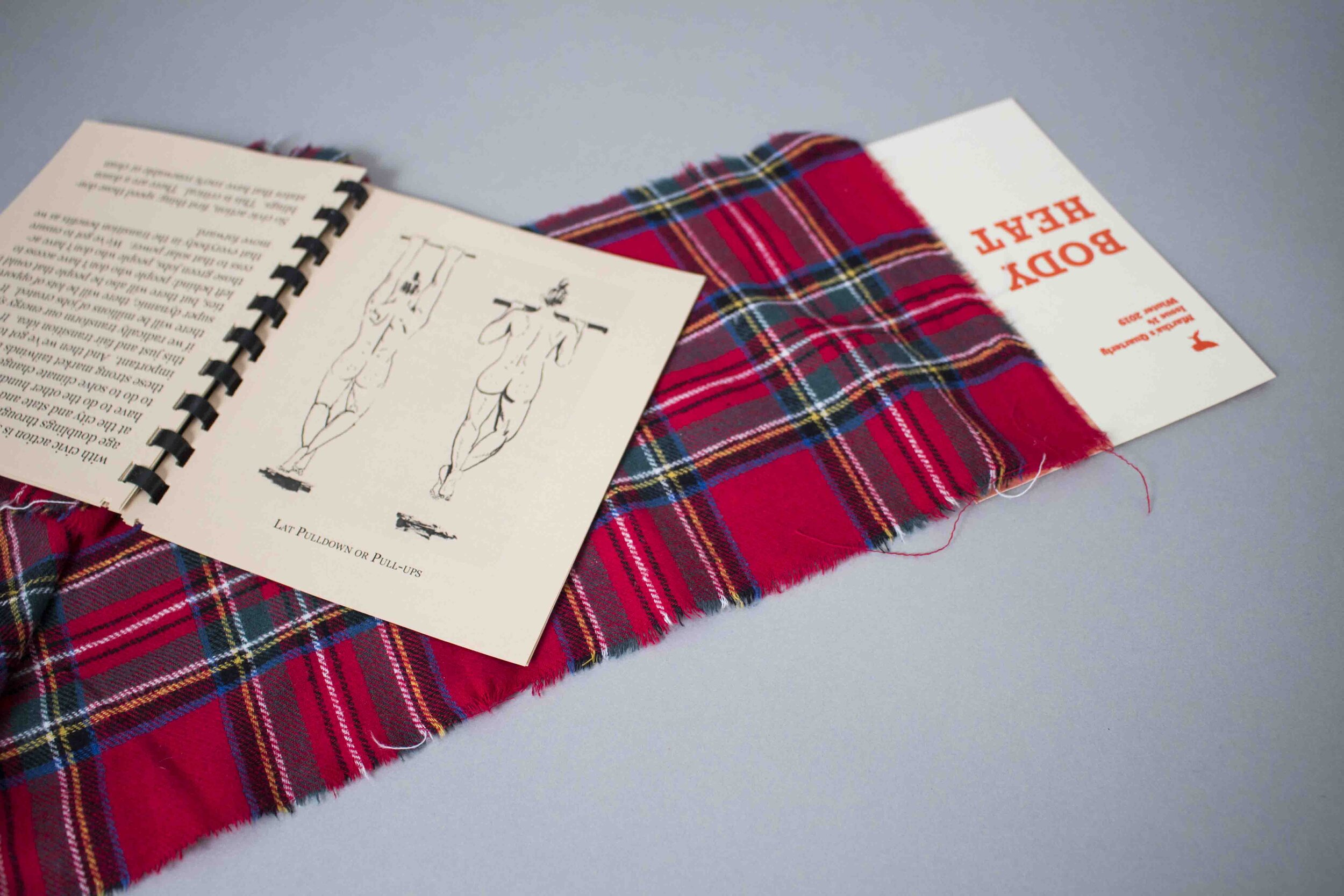

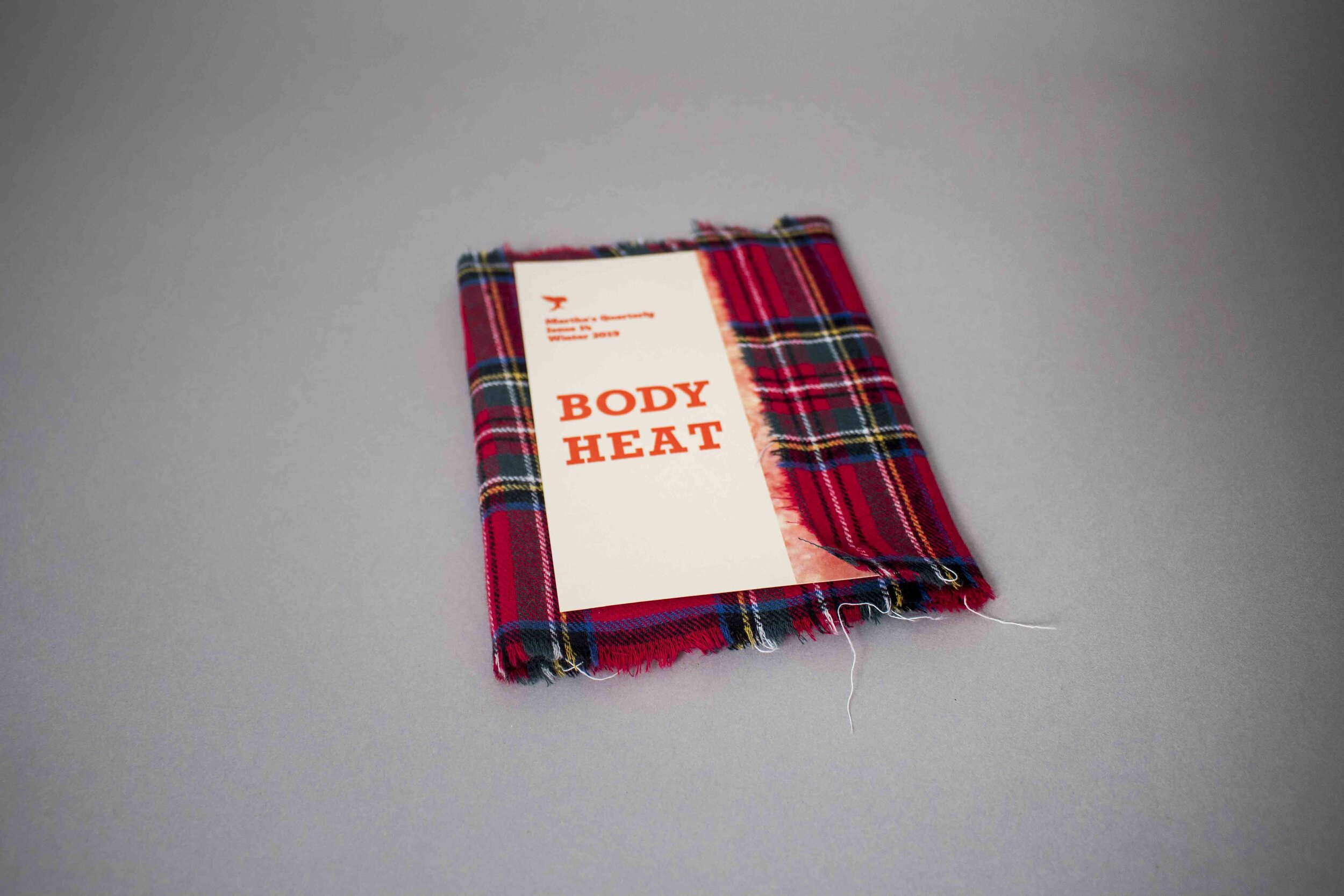

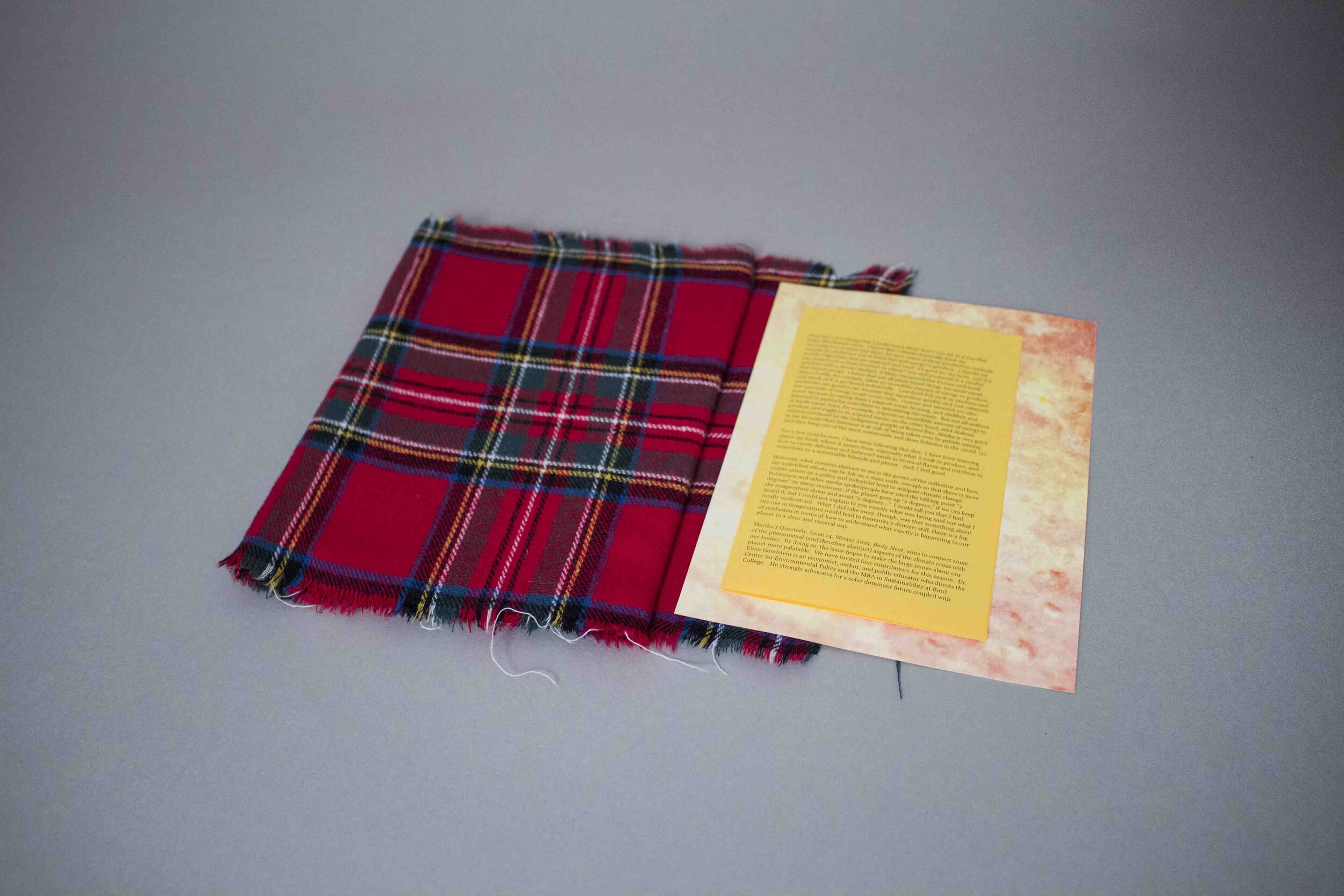

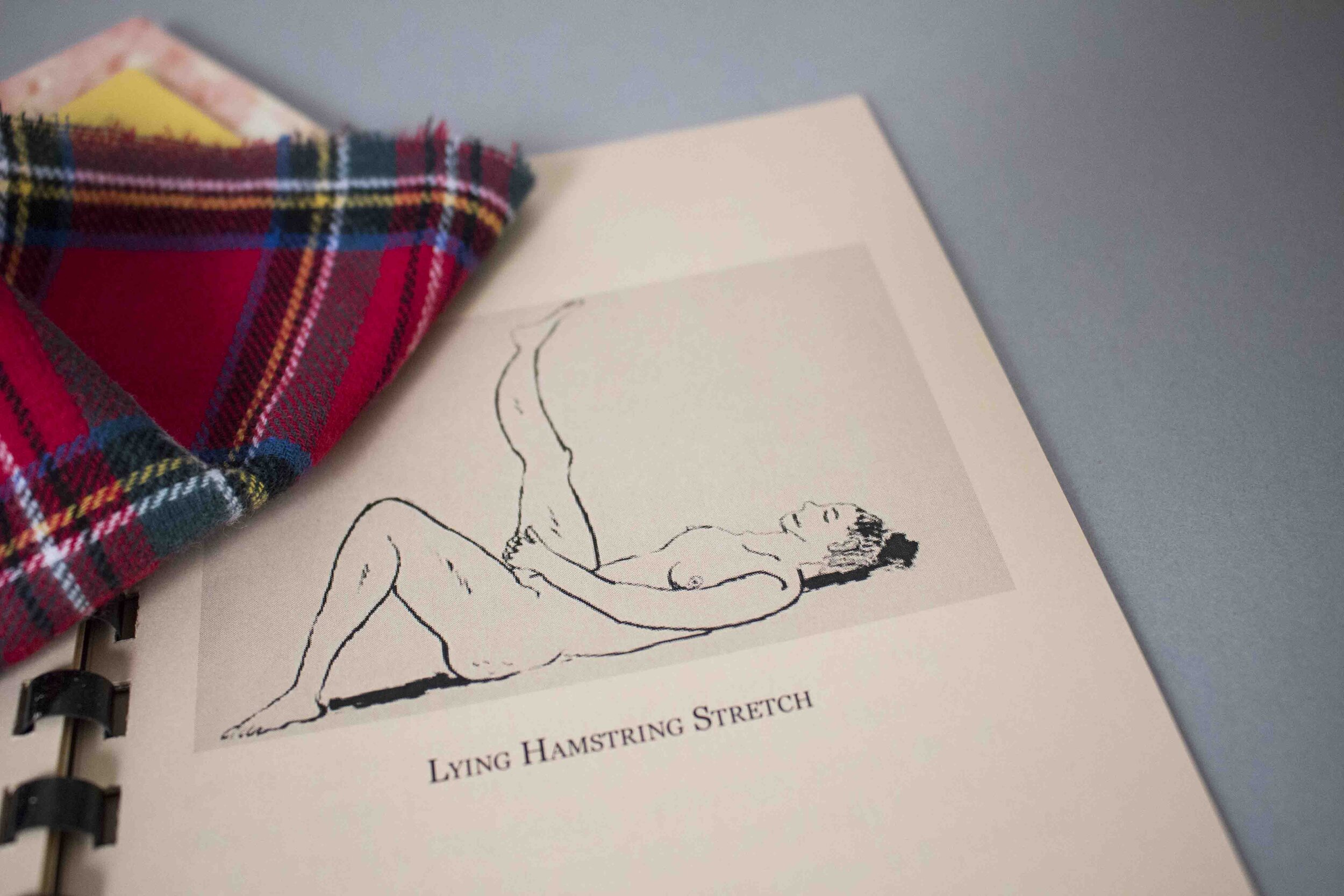

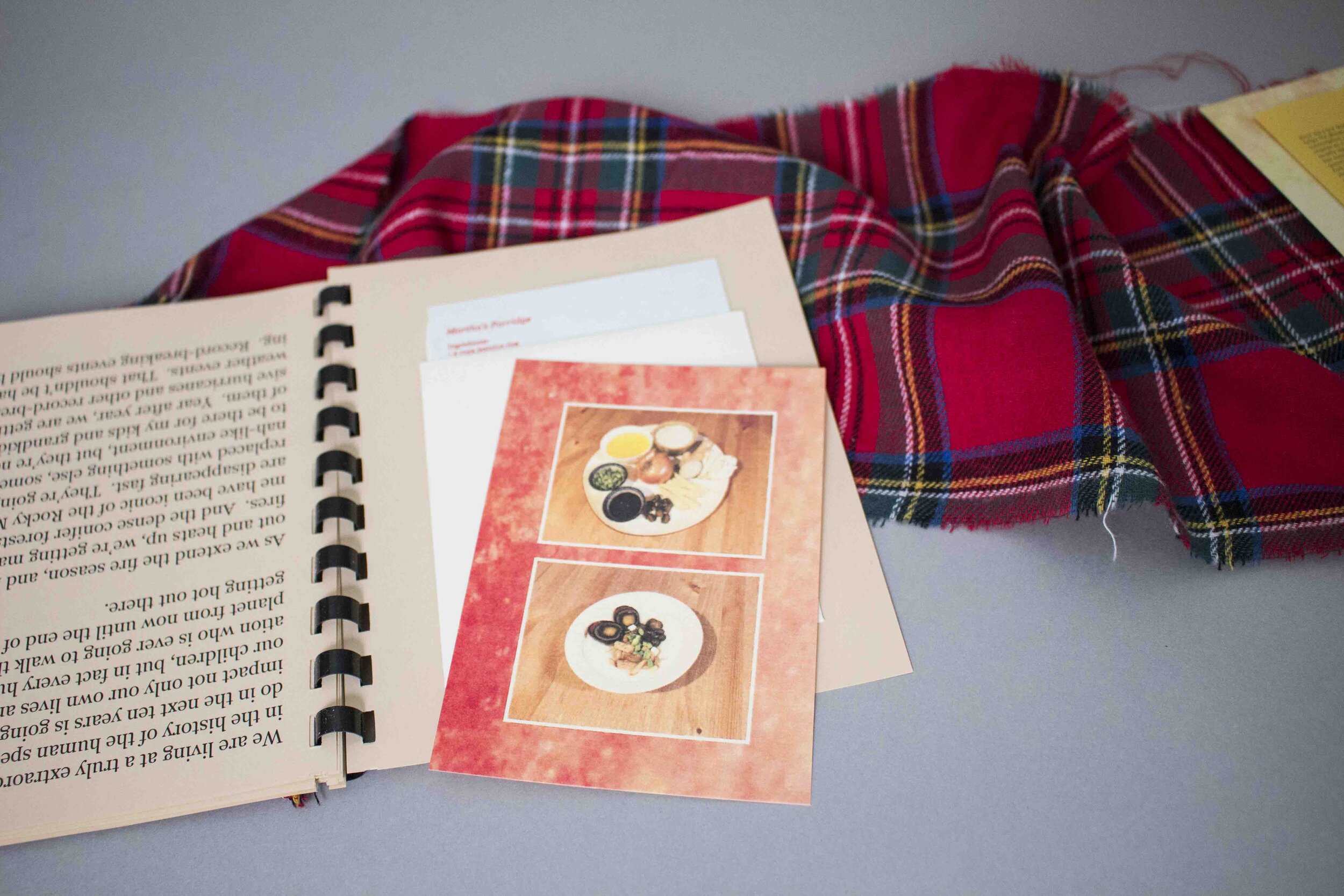

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 14, Winter 2019, Body Heat, aims to connect some of the phenomenal (and therefore abstract) aspects of the climate crisis with our bodies. By doing so, the issue hopes to make the large issues about our planet more palatable. We have invited four contributors for this season. Dr. Eban Goodstein is an economist, author, and public educator who directs the Center for Environmental Policy and the MBA in Sustainability at Bard College. He strongly advocates for a solar dominant future coupled with civic action. His piece goes into the details of his infrastructure vision, but he offered one of the most compelling analogies to the condition of our planet’s suffering. At the beginning of his text, he compares the climate crisis to getting a fever, that the atmosphere around the earth is like an apple skin or a blanket, and that just as we can each die from a prolonged fever, the Earth will head inevitably towards its demise if the temperature increases more than the 2 degrees Fahrenheit it has already increased by. Passenger Pigeon Press took this analogy and expanded it into an exploration of our bodies in the context of a fever. We did so by inviting Nicholas Cerone, a physical trainer, and Irene Gardner, a nutritionist, to offer remedies in exercise and dieting that can manage and reduce a fever. Their advice is functional and useful to relating issues of the planet’s crisis to our own bodies in crisis.

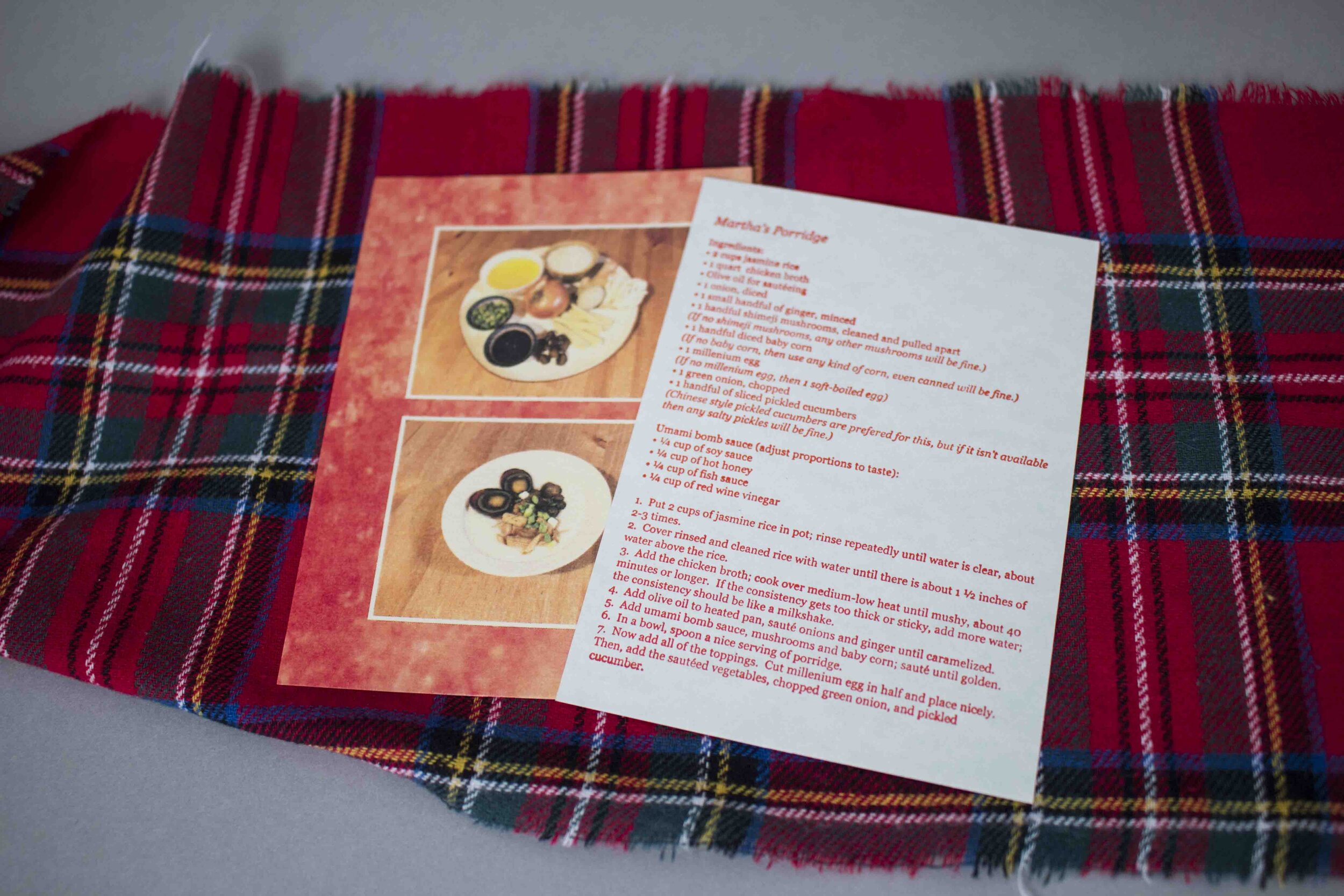

The structure of this book is evocative of care and aims to further emphasize the relationship between our singular human bodies and the earth. When you first see this book, it is wrapped in a flannel “blanket;” as it unravels, you’ll see that one way of reading the book features Dr. Goodstein’s writing, and when you flip it over you can read Mr. Cerone and Ms. Gardner’s contributions. Then, you’ll further notice that the background texture is the skin of a fuji apple, referring back to Dr. Goodstein’s analogies.

I would also encourage you to take some of Mr. Cerone’s and Ms. Gardner’s advice by following the drawings made by Drea Coffield that accompany the weight and stretching routines, and by cooking “Martha’s porridge,” which we created as inspired by Ms. Gardner’s nutritional prescription.

Just this last Dec. 12, 2019, the British elections resulted in a landslide victory for the Conservative party. This implied overwhelming support for Boris Johnson’s proposal to complete Britain’s departure from the European Union by January 31, 2020. (2) In the wake of this, I was reminded of Al Gore’s speech at an event on his sequel documentary An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power when he boldly claimed that climate change caused Brexit. In his 2017 explanation, he described that the “principal” cause of the Syrian Civil War was the extreme drought that caused the “incredible flow of refugees into Europe, which is creating political instability and which contributed in some ways to the desire of some in the UK to say ‘Whoa, we’re not sure we want to be part of that anymore.” He further went on to say, “Some countries have a hard time even in the best of seasons, but the additional stress this climate crisis is causing really poses the threat of some political disruption and chaos of a kind the world would find extremely difficult to deal with.”(3)

This relationship between people and the climate crisis is something that I think should be treated with more of a wartime mentality– when people come together, see the connections between the environment and political tension, and rally towards mitigating the problem with collective power. However, because the relationship between people and the environment has to be explained through several linked relationships, like what Vice-president Gore described, the urgency gets lost.

I’ll part with this. Last Christmas (around the time this issue is being published), I entered a lovely stone cottage in County Tyrone of Northern Ireland, an area with many folks supportive of Brexit. There I was, in a beautiful warm home talking to an old man who turned out to be Pierce Kelly, the former drummer of the legendary hard rock band Thin Lizzy. I was smitten; he even wore a monocle. He was an old friend of my husband, and it had been a while since they had seen each other. We were warmly welcomed with hot tea and a basket of Christmas biscuits. As we talked, one thing led to the next, and we soon learned that Mr. Kelly didn’t think that Brexit was all too bad of an idea. Something needs to be done about the refugees, his many explanations expressed. I didn’t get a sense that Mr. Kelly disliked the refugees for being different; rather, I felt more of a sense of resentment and apprehension towards the local chaos the massive migration of people presented: it felt unstable and threatening. I really appreciated listening to Mr. Kelly, and it was the first time I heard firsthand from a person who supported the Brexit cause. My political opinions still differ, and we did not once talk about climate, but what is important to note here is the tea, the biscuits, and the warmth. While this issue tries to connect our planet with our personhood, I think that it also tangentially tries to hint at something else– which is that body heat, expressed through our compassion for one another over food and stories, is a reliable way to listen to the other side.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1) The climate crisis is an ocean crisis, The Ezra Klein Show, interview with Dr. Ayanna Elizabeth Johnson

(2) Results breakdown of the 2019 United Kingdom general election, Wikipedia

(3) Independent, Climate change helped cause Brexit, says Al Gore, by Ian Johnston, March 23, 2017

Martha's Quarterly

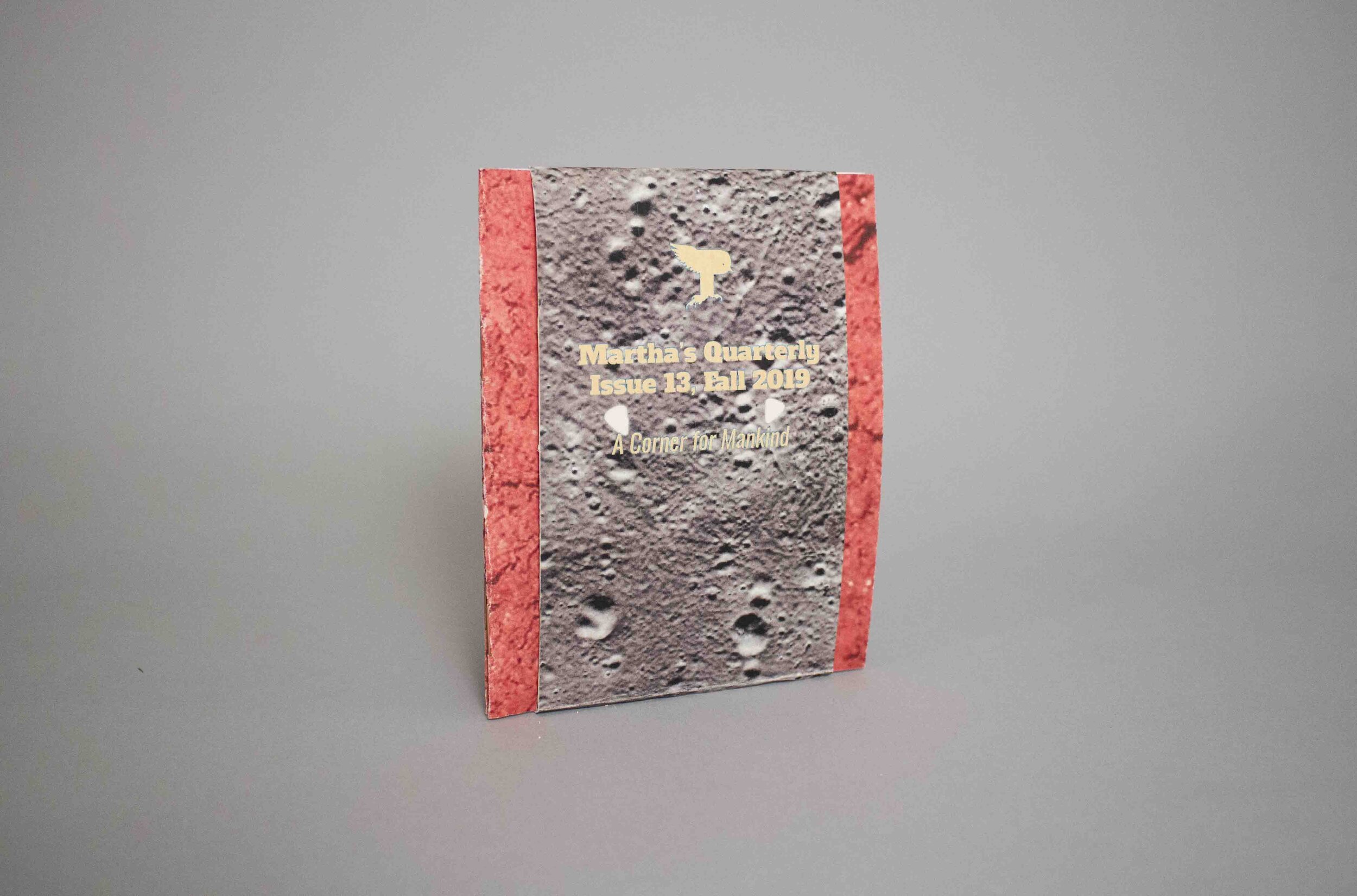

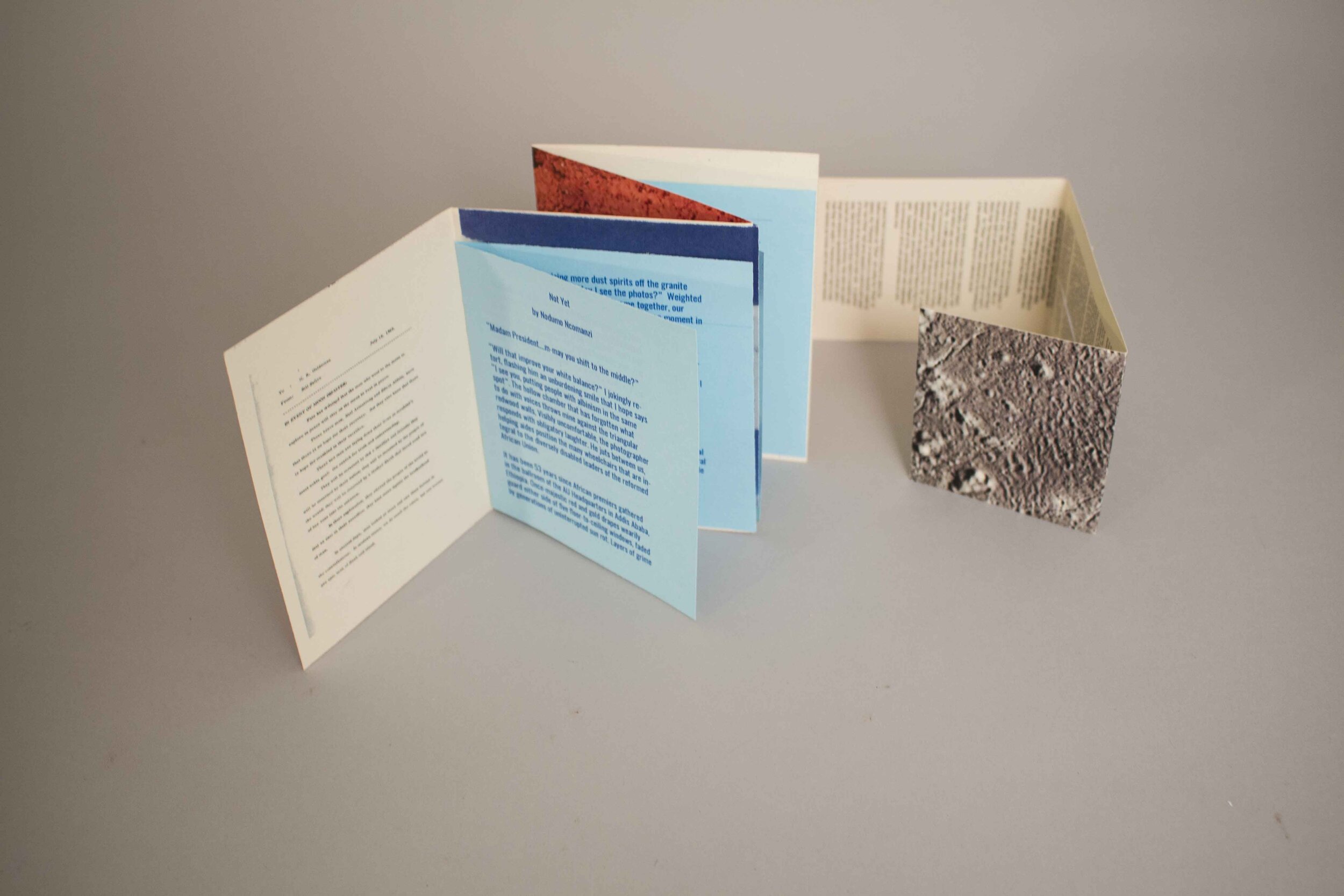

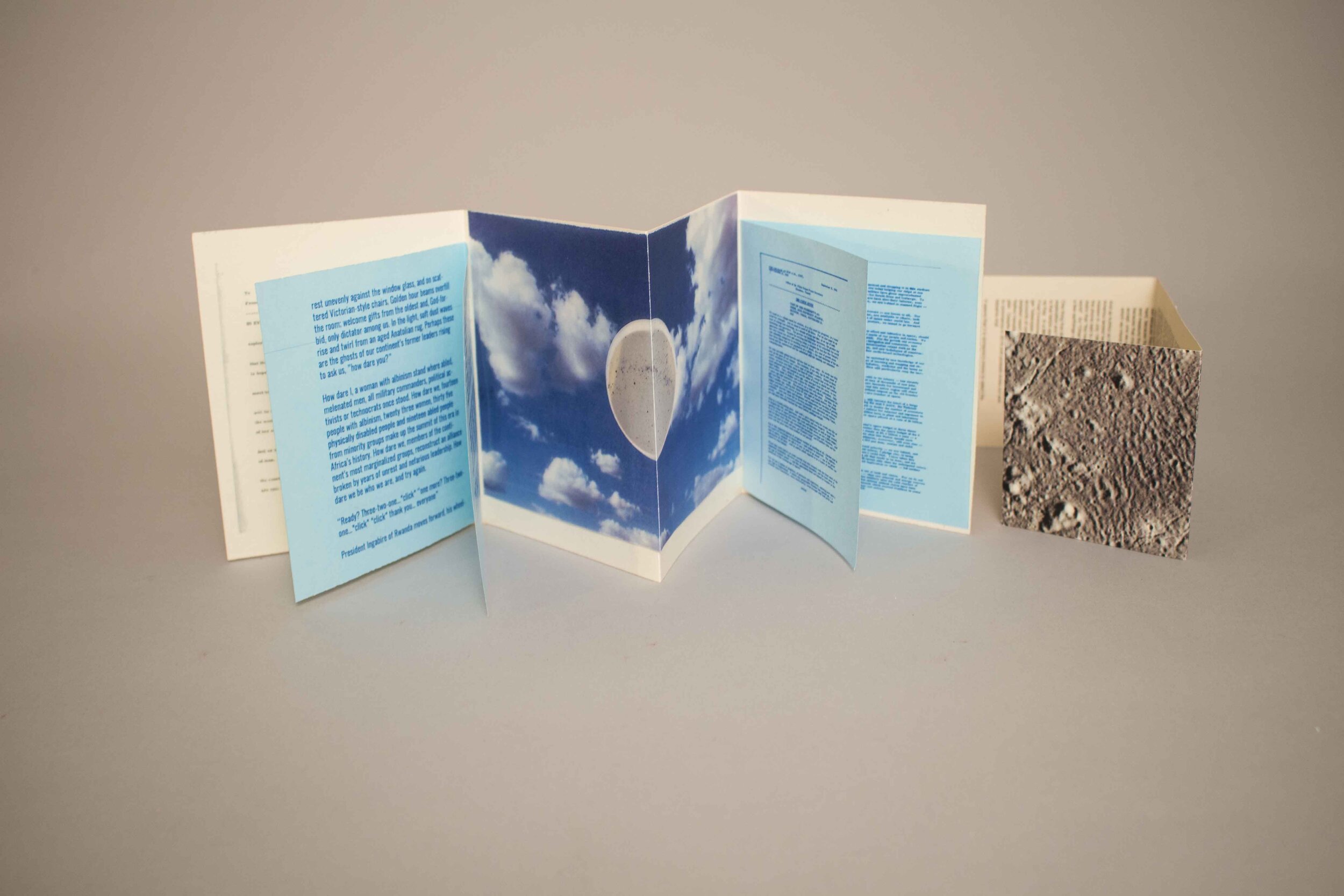

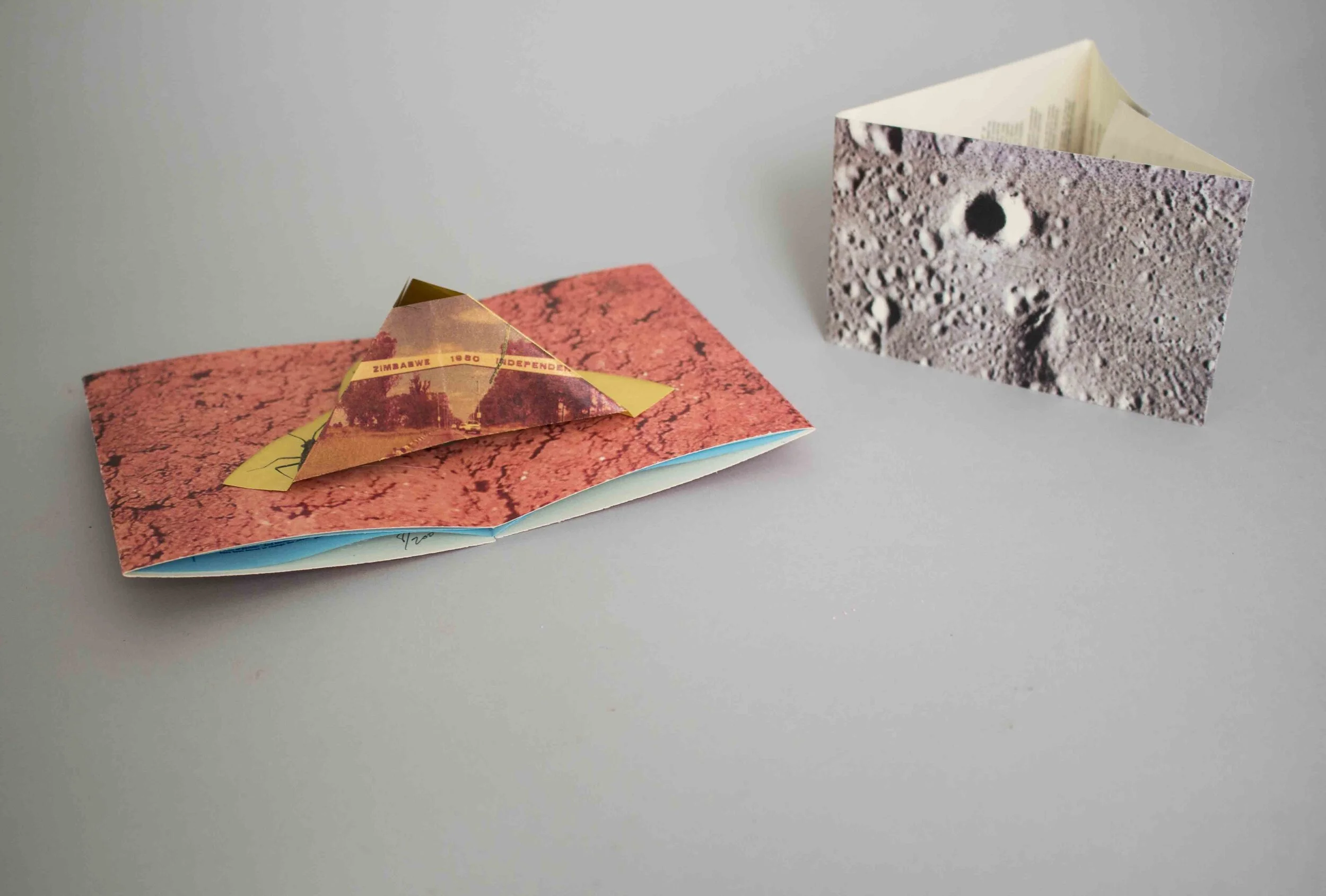

Issue 13

Fall 2019

A Corner for Mankind

5” x 4”

About the contributors:

Nodumo Ncomanzi is a radical African with albinism. They love snakes and are tired of being excluded from crucial spaces, such as governance.

John F. Kennedy was the 35th president of the United States of America.

William Safire was an author, columnist, lexicographer, journalist, and political speechwriter.

Last July, a protest about a telescope to be built on the big island of Hawaii went viral on my social media. The protesters opposed the construction of an enormous observatory, called the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), to be built on the volcano Mauna Kea. The TMT proposes the most grandiose technologies that can “capture images ‘that look back to the beginning of the universe.’”(1) The protesters argue that the construction of this observatory will continue to devastate Mauna Kea, which is already home to many telescopes. Many of the protestors are scientists who have already been working on the volcano and Native Hawaiians who consider themselves kia‘i, or protectors.

Tensions on Mauna Kea date back to 1893, when the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown and Hawaiians lost their land and their culture. Mauna Kea is a particularly contentious site because it is sacred to Hawaiians and is known as the home to Wakea, the sky god. On the other hand, Mauna Kea is an idyllic place for astronomical observations and research because the summit is so high that the air is arid, dry, and free of atmospheric pollution. Development for astronomical research has been active, even encouraged, on Mauna Kea since the 1960s. Today there are 13 observational facilities funded by as many as 11 countries.

There are many points of tension in this conflict; one concerns the controversy surrounding the TMT and is about which “Others” deserve respect, attention, and protection. Do we honor the Hawaiians and their faith? Or, do we honor science and its enormous curiosity for the extraterrestrial? The Hawaiians are “Others” to corporations and governments that do not recognize their culture as significant enough to supercede their investing in knowing another “Other” which they believe could advance their idea of humanity.

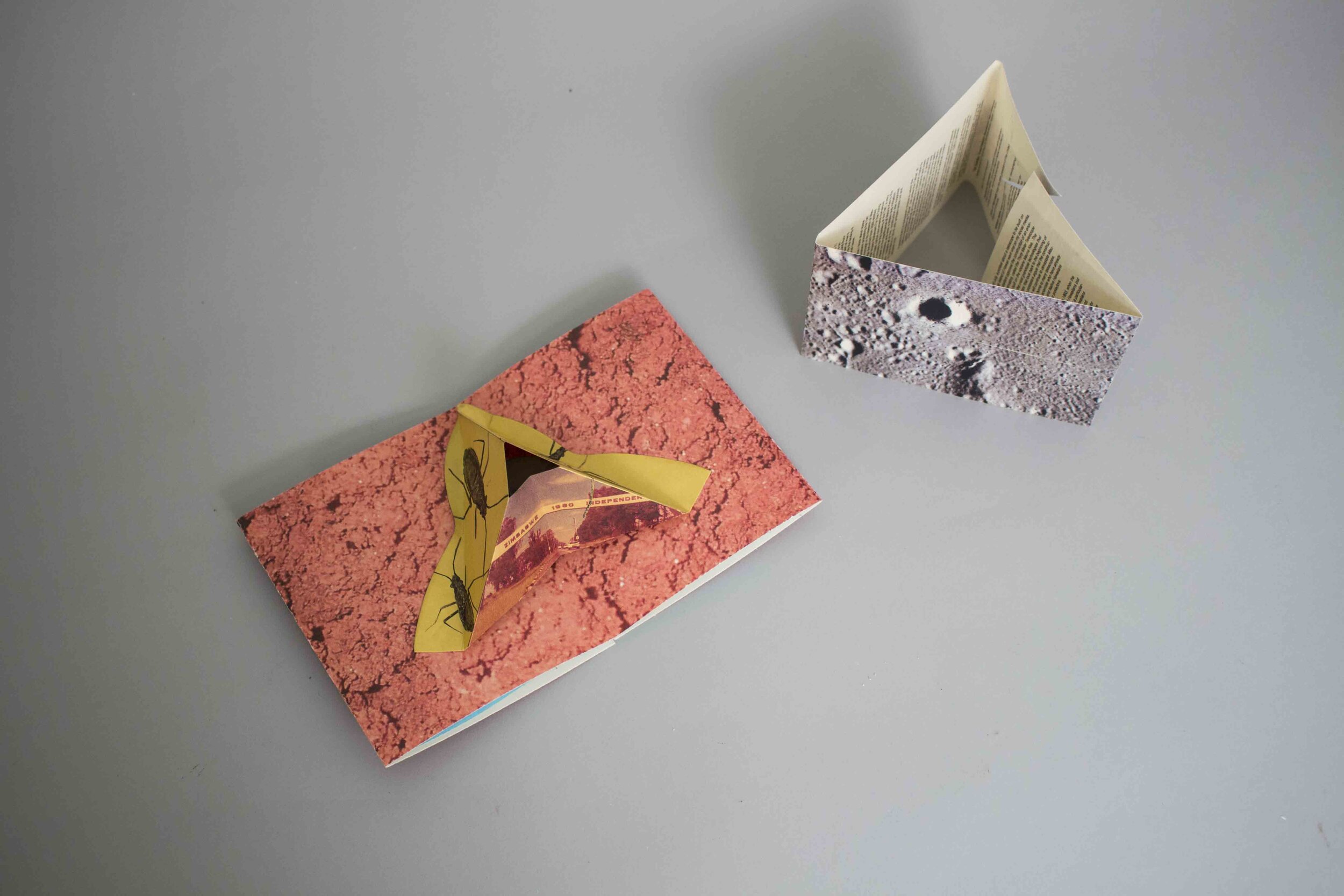

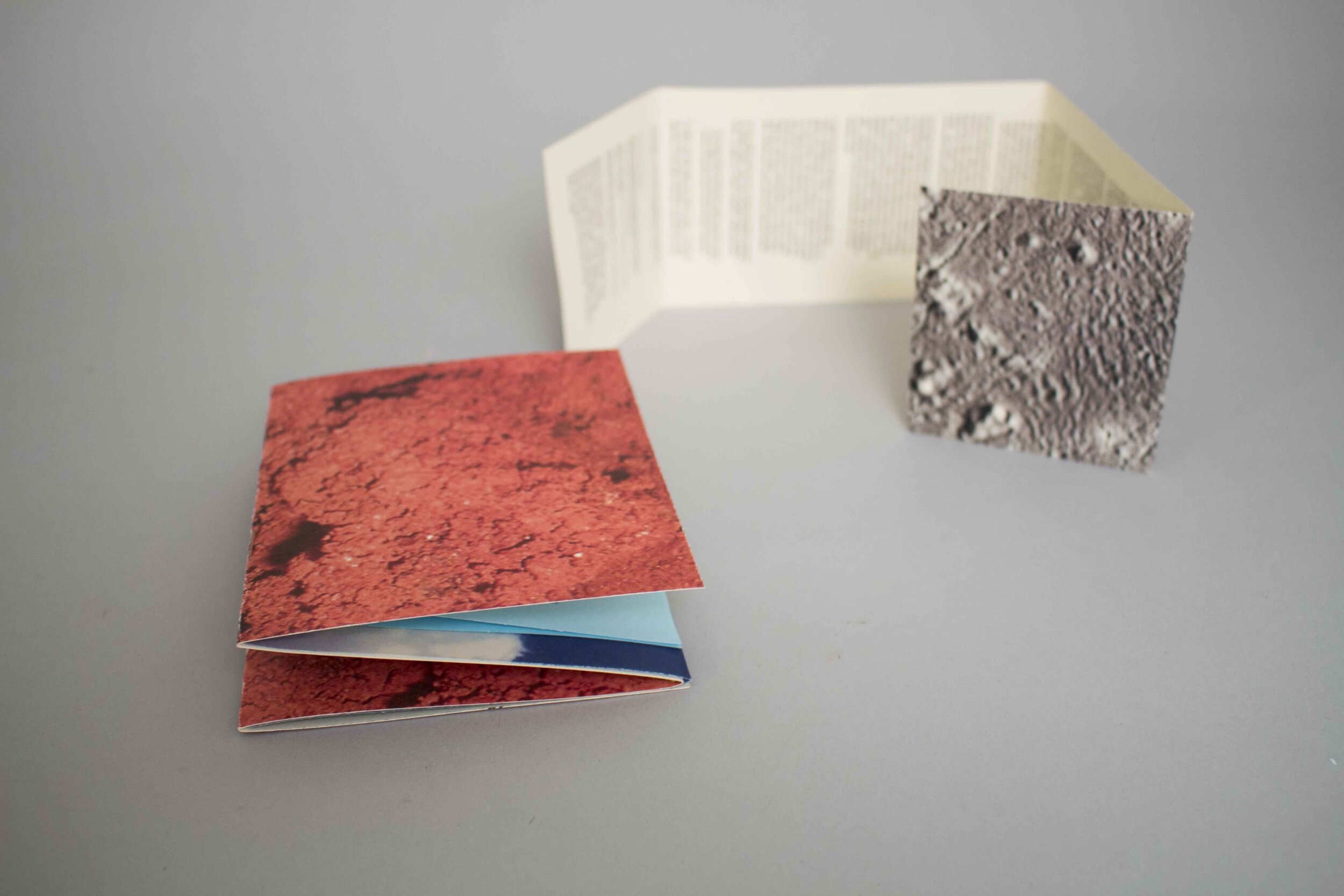

And so, this issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 13, Fall 2019, A Corner for Mankind, brings together disparate subjects that aim to stretch our imagination from humans to the moon and back.

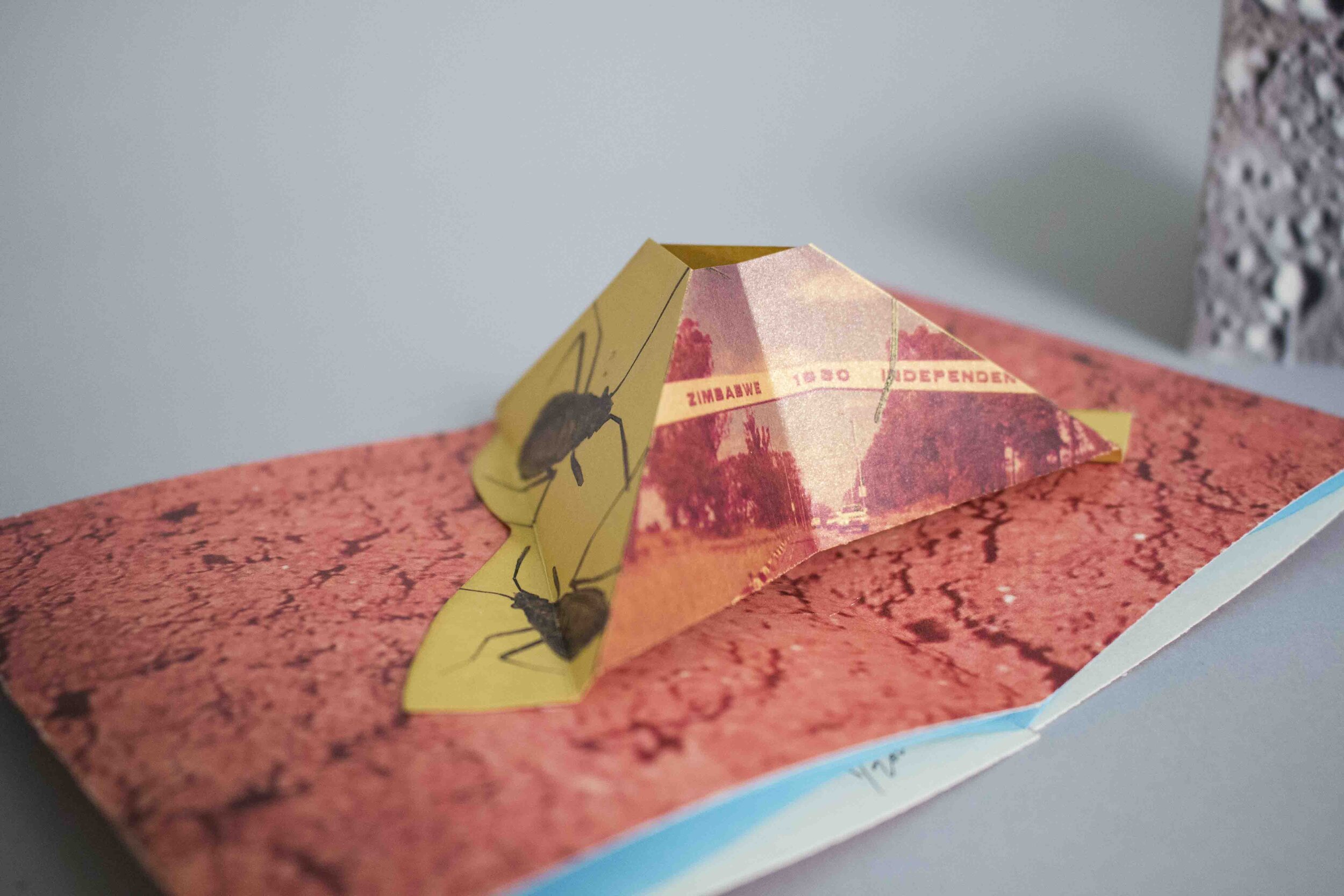

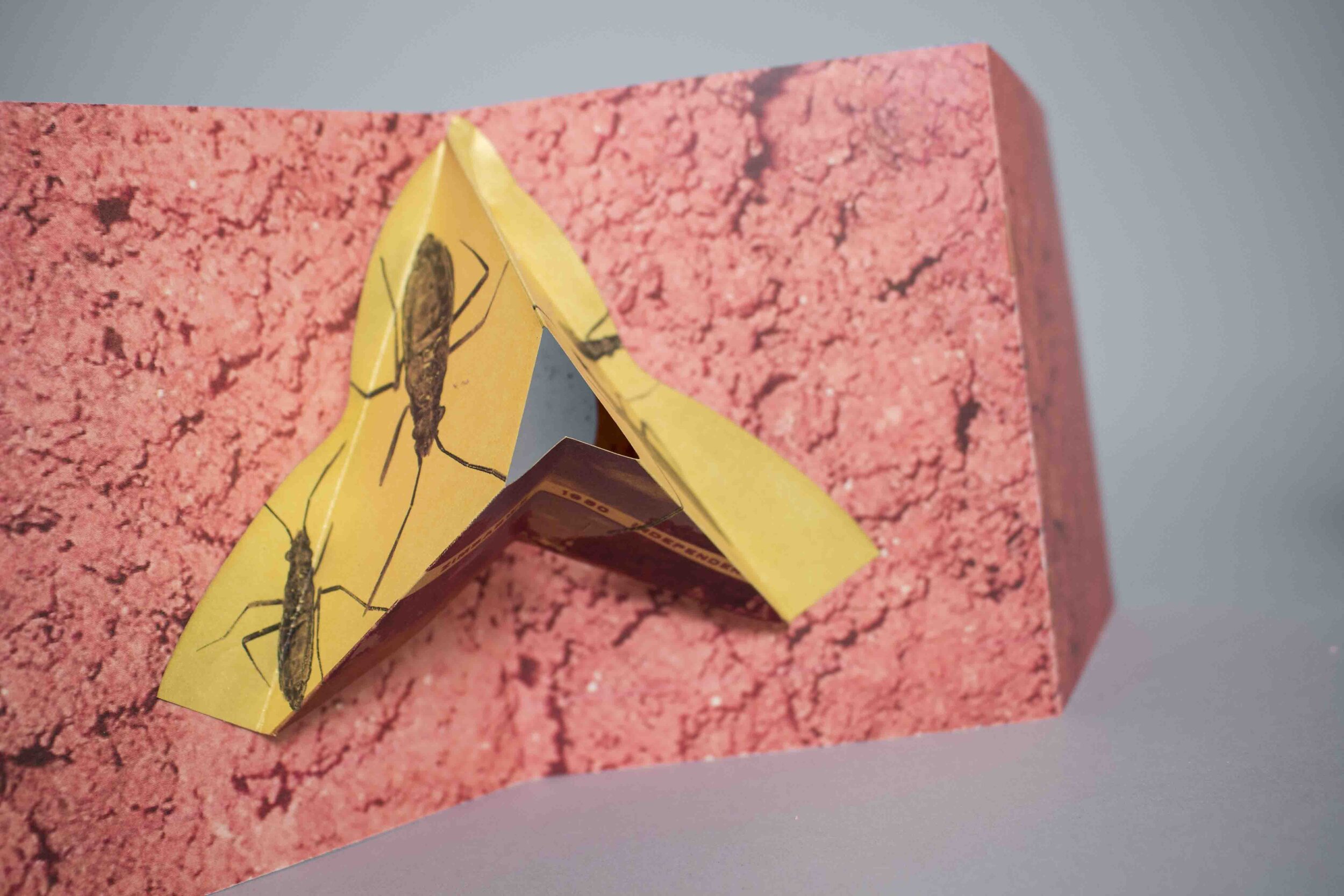

The centerfold of this zine presents a pop-up volcano graced by illustrations of the Wekiu bug, an insect that thrives on Mauna Kea. Despite the extreme temperatures that can fluctuate between 108F and 25F and there is virtually no plant life, the Wekiu bug has found a way to thrive: by feeding off the insects that are carried by the wind to the mountain top to die.

When you look inside the volcano, it turns into a sort of telescope wherein you can see an illuminated map of the stars from the planet’s Southern Hemisphere that blankets many of humanity’s “Others”, including those on the continent of Africa. In one of the signatures is a short story by Albinism awareness activist Nodumo Ncomanzi, who pens a futurist fiction where people with albinism have taken over governmental reins across Africa. The protestors that flood Harare’s Airport Road in her narrative are remembered in the pop-up volcano: a distorted image of the modern road is centered inside of the volcano, making this particular model of Mauna Kea, a mountain of the mind, occupied by the conscience of the “Other” from within.

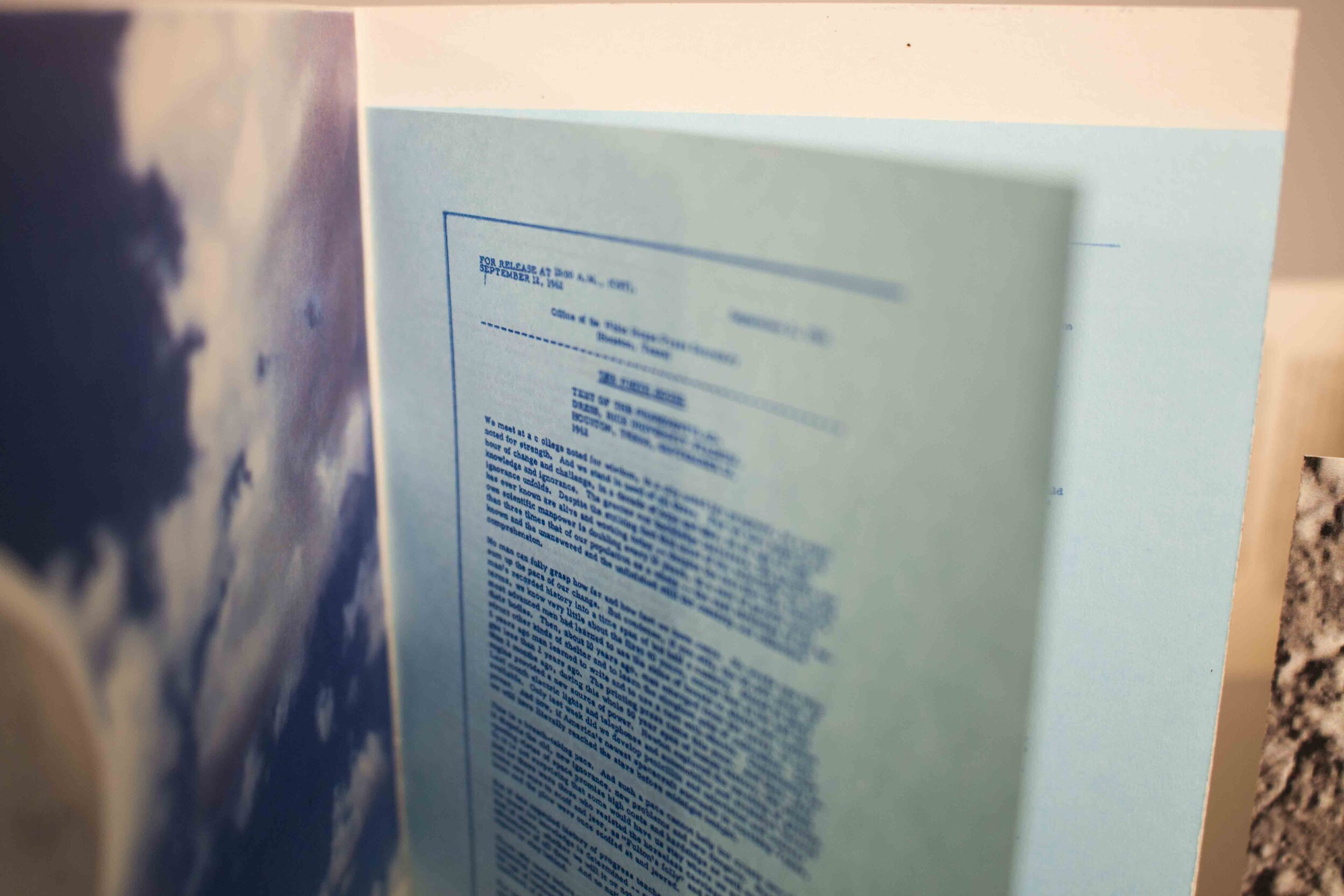

In the other signature is another futurist fiction by a man who held the government reins of America for a short time. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy gave a speech at Rice University wherein he rallied America to be excited about putting a man on the moon, a race between American and the Soviet Union. In his famous speech he sermonized:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

And as truthful as fate could ever be to a choice, America landed two men on the moon in the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 under President Nixon, who on the phone said to astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin that “the heavens have become a part of man’s world”. An “Other” had been obtained by the landing of a few earthlings seeking out a national cause.

One thing that disturbs me when I think about space exploration and Native Hawaiians protesting the TMT is that NASA was very thorough in its research of Mauna Kea. In a 660 page document from 2005 entitled Final Environmental Impact Statement For the Outrigger Telescopes Project, NASA documents numerous accounts of concern for the building of the TMT, a very detailed report on the significance of Mauna Kea to the Native Hawaiians, and even a Wekiu bug mitigation plan. Despite all of this, construction was supposed to commence in 2018 until protests broke out and became viral.

It seems that it is someone’s choice to select the Native Hawaiians as “Other”, but unlike the “Other” of space, the “Othering” of humans is a decision made by the “non-Other” that some people’s customs and ways of living are not as important as their own. In another way, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s humanity was turned into a proxy for America: they were two earthlings who became representative of a whole nation. Had they not made it, America knew it had to keep their memory as human and not a national mission.

On the sides of this zine is a back-up speech prepared by William Safire, who was President Nixon’s speechwriter. In case of a “Moon Disaster”, Safire penned:

For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.

In death, but with ease, the moon is man. It is one of us, but never will the Hawaiians, or those of us with albinism, or the Wekiu bug be a man like the moon.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1)The Guardian, 'A new Hawaiian Renaissance': how a telescope protest became a movement, by Michelle Broder, August 17, 2019.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 12

Summer 2019

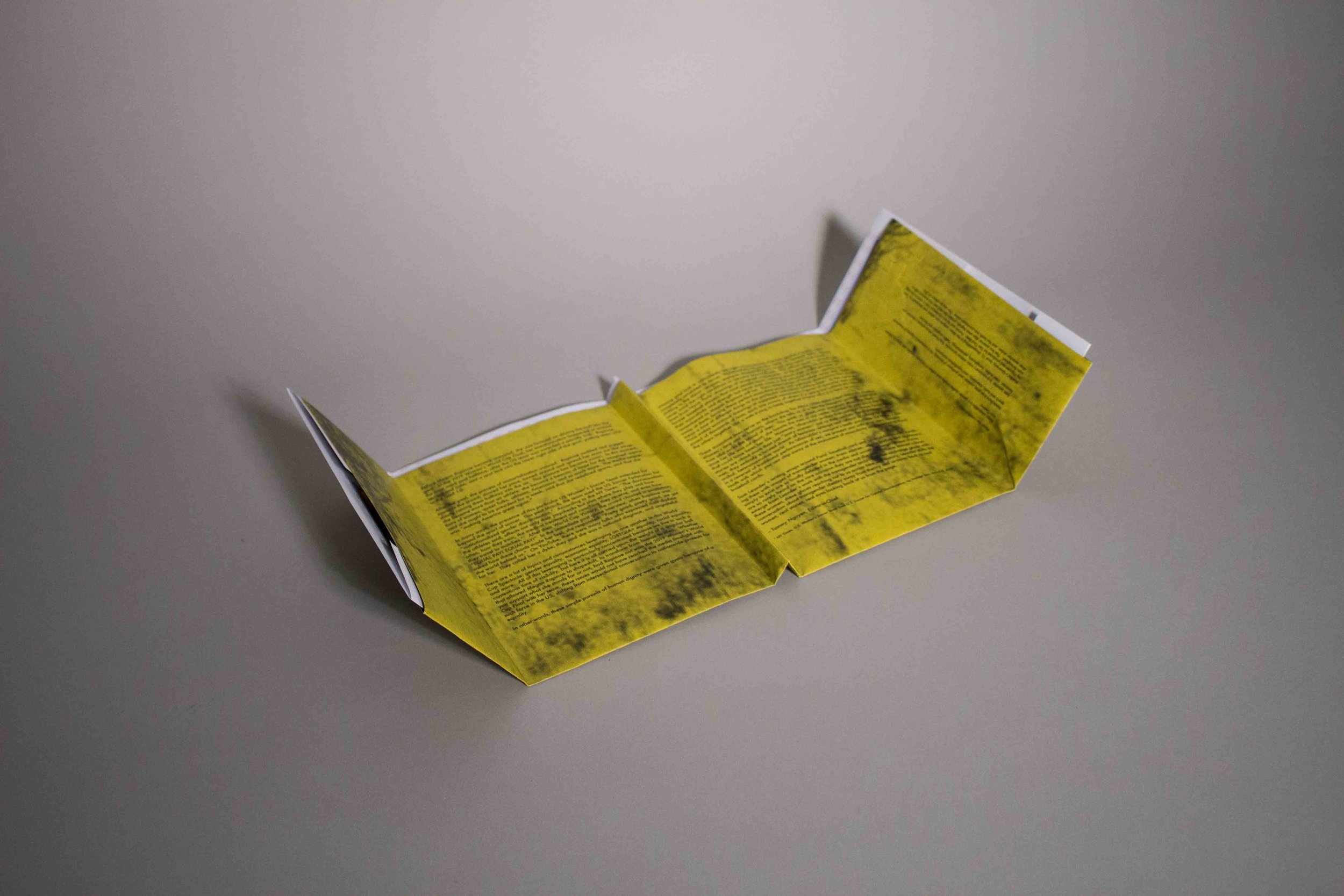

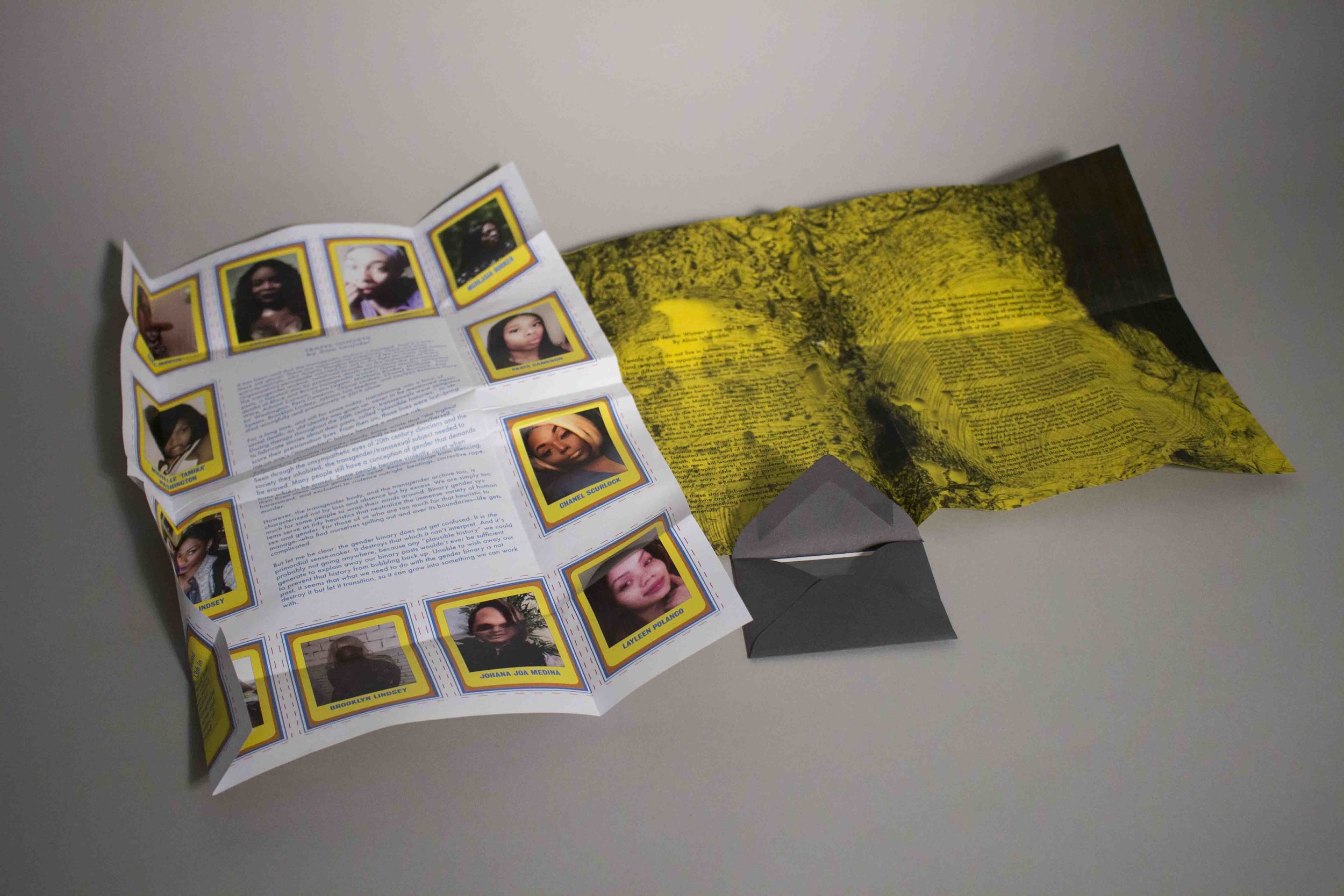

Shapeshifting in the Minor Leagues

6.5” x 4.75”

About the contributors:

Alicia Izharuddin is a gender studies scholar and author of the book Gender and Islam in Indonesian Cinema.Norm Paris is an artist, curator, and professor of drawing. He is interested in figures of American sports and music, flawed masculinity, and hypothetical monuments.

Sam Leander is a non-binary trans woman (pronouns: they/them) whose primary interests are feminism, trans studies, metaphysics, epistemology, Netflix originals, and the law.

Before Megan Rapinoe became immortal, she was focused on driving the ball into the goal. In the 2019 Women’s World Cup Final, her transformation happened at around the hour mark past halftime, after the US team was awarded a penalty kick. Rapinoe, serious and calm, sent a spot kick into the lower right side of the goal, putting team USA in the lead 1-0.

After the goal, the process of immortalization occurred. Rapinoe nodded and jogged towards the crowd, slowed her pace, turned around and spread her arms out like wings, slowly raising them halfway into the air. This posture has become iconic. In this moment, she became more than an athlete; she became a beacon of hope for the imagined aspirations of women, queer folks, athletes, Americans, and so much more. The media swarm said she ought to be president for a week, said that she redefined sports, said that she was “making America great again.”

In many ways, the presence of this particular US Women’s Soccer Team extended far beyond the sport of soccer. This past March, the team sued the US Soccer Federation for “institutionalized gender discrimination.” According to the NY Times, “The discrimination, the athletes said, affects not only their paychecks but also where they play and how often, how they train, the medical treatment and coaching they receive, and even how they travel to matches.” (1) After their World Cup Victory, the crowd chanted in exaltation, “EQUAL PAY! EQUAL PAY!” In the immediate post game interview, when Rapinoe was asked how these chants made her feel, she responded: “Pretty good, pretty good, we got the world behind us.” On YouTube, there were many folks who expressed their disdain for her. They called her a dyke; they said she was a national disgrace, and ungrateful.

There are a lot of topics and circumstances leveraging on one another in this World Cup Spectacle: gender equality, economic equality, LGBTQIA+ equality, racial equality, and more. All of this leveraging is particularly concentrated because we live in such a contentious time of visibility, but here it is all carried upon the weight of a singular ball that allowed Megan Rapinoe to shapeshift, to transform from human to idea. Whether you support what she stands for or not, had Rapinoe not won the 2019 Women’s World Cup Final with her team, these issues would not have reached the media limelight with such force in the US, shifting from intersectional conversations to nationwide protests for equality.

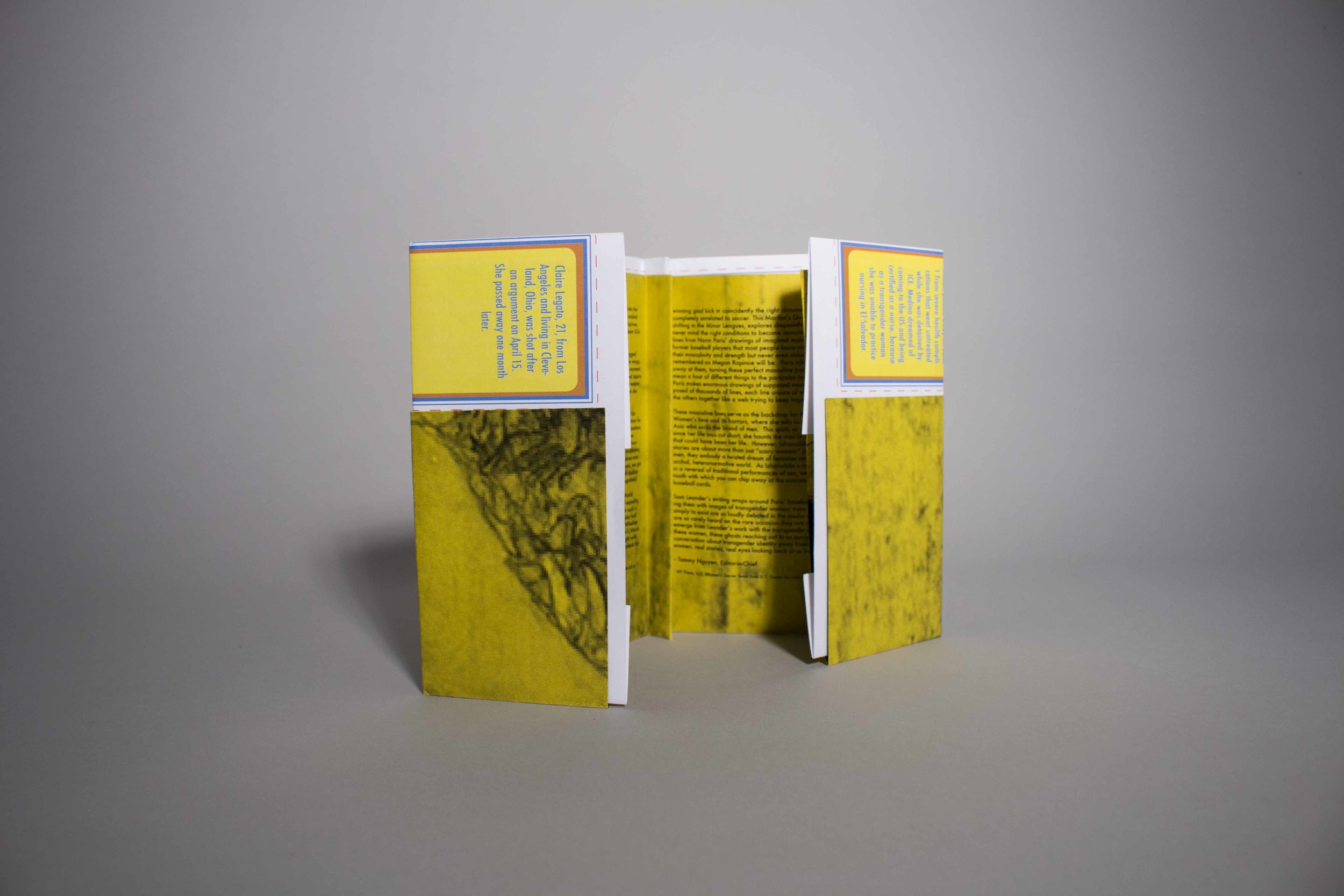

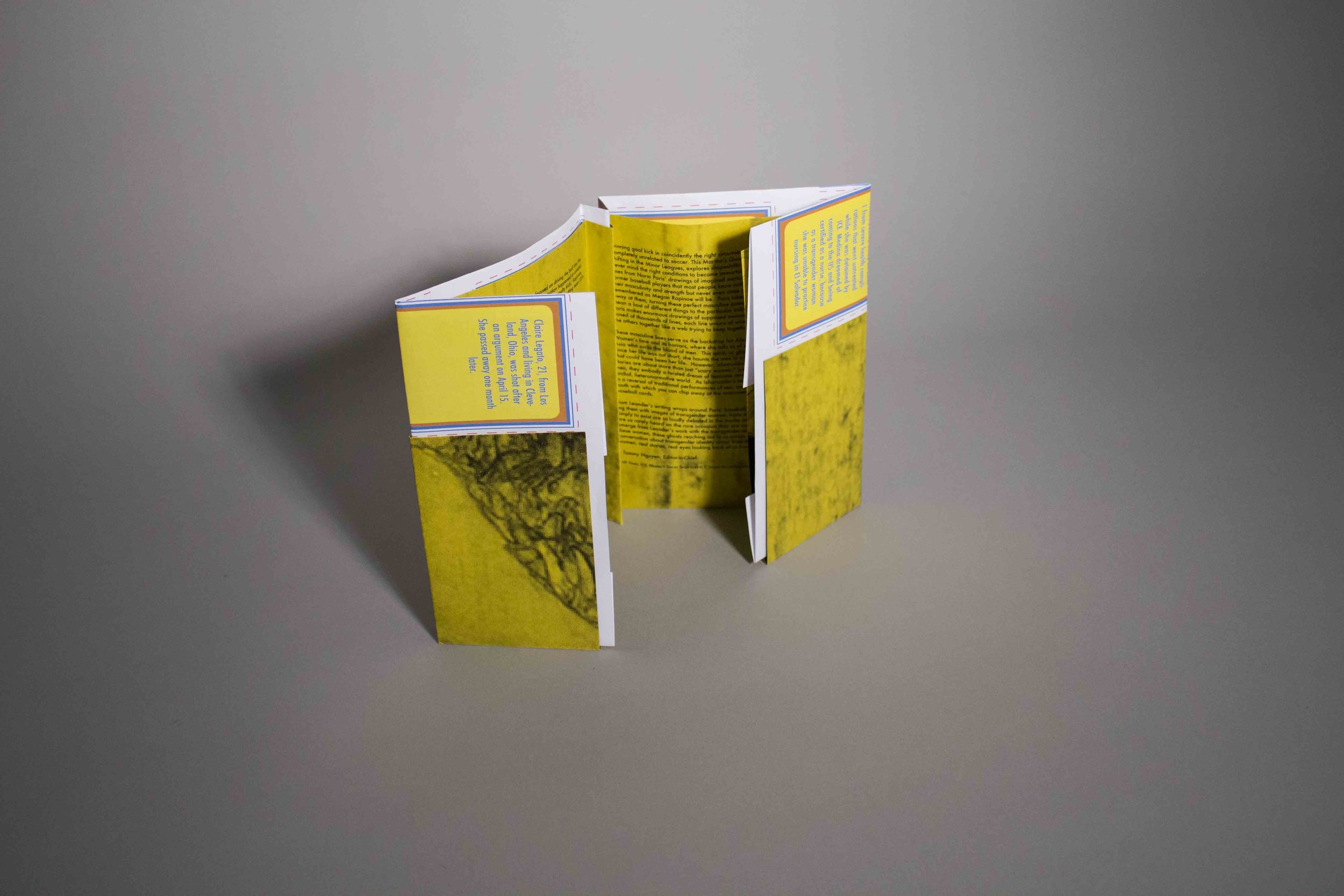

In other words, these simple pursuits of human dignity were given gusto because of a winning goal kick in coincidently the right circumstances that has ignited a public spirit completely unrelated to soccer. This Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 12, Summer 2019, Shapeshifting in the Minor Leagues, explores shapeshifting by those who never had a ball, never mind the right conditions to become immortalized. The yellow cover is grazed with lines from Norm Paris’ drawings of imagined monuments. In his practice, he excavcates former baseball players that most people know nothing about, men at the pinnacle of their masculinity and strength but never even close to the pinnacle of their sport to be remembered as Megan Rapinoe will be. Paris takes heaps of baseball cards and sands away at them, turning these perfect masculine poses into agitated abstractions that could mean a host of different things to the particular individual holding them. At the same time Paris makes enormous drawings of supposed monuments, figures of muscular men composed of thousands of lines, each line unsure of where it is going but collectively holding the others together like a web trying to keep together a hero who is a hero no more.

These masculine lines serve as the backdrop for Alicia Izharuddin’s text Untimely deaths: Women’s time and its horrors, where she tells us of a female vampiric spirit of Southeast Asia who sucks the blood of men. This spirit, or ghost, was pregnant when she died; since her life was cut short, she haunts the men in our realm in order to gain back the time that could have been her life. However, Izharuddin probes that perhaps these vampires stories are about more than just “scary women:” just as they contain the nightmares of men, they embody a twisted dream of feminine revenge and refusal to submit to a patriarchal, heteronormative world. As Izharuddin’s vampire’s teeth punctures the male’s skin in a reversal of traditional performances of sex, we present you with your own vampire tooth with which you can chip away at the monument of masculinity as presented in Paris’ baseball cards.

Sam Leander’s writing wraps around Paris’ baseball card and Izharuddin’s tooth, swathing them with images of transgender women: trans women, whose bodies and legitimacy simply to exist are so loudly debated in the media and society at large, whose stories are so rarely heard on the rare occasion they are not dismissed. These women’s faces emerge from Leander’s work with the transgender archive; as we exchange gazes with these women, these ghosts reaching out to us across time and history, Leander shifts the conversation about transgender identity away from theory and archives back to real women, real stories, real eyes looking back at us from the page.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1) New York Times, U.S. Women’s Soccer Team Sues U.S. Soccer for Gender Discrimination by Andrew Das, March 8, 2019.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 11

Spring 2019

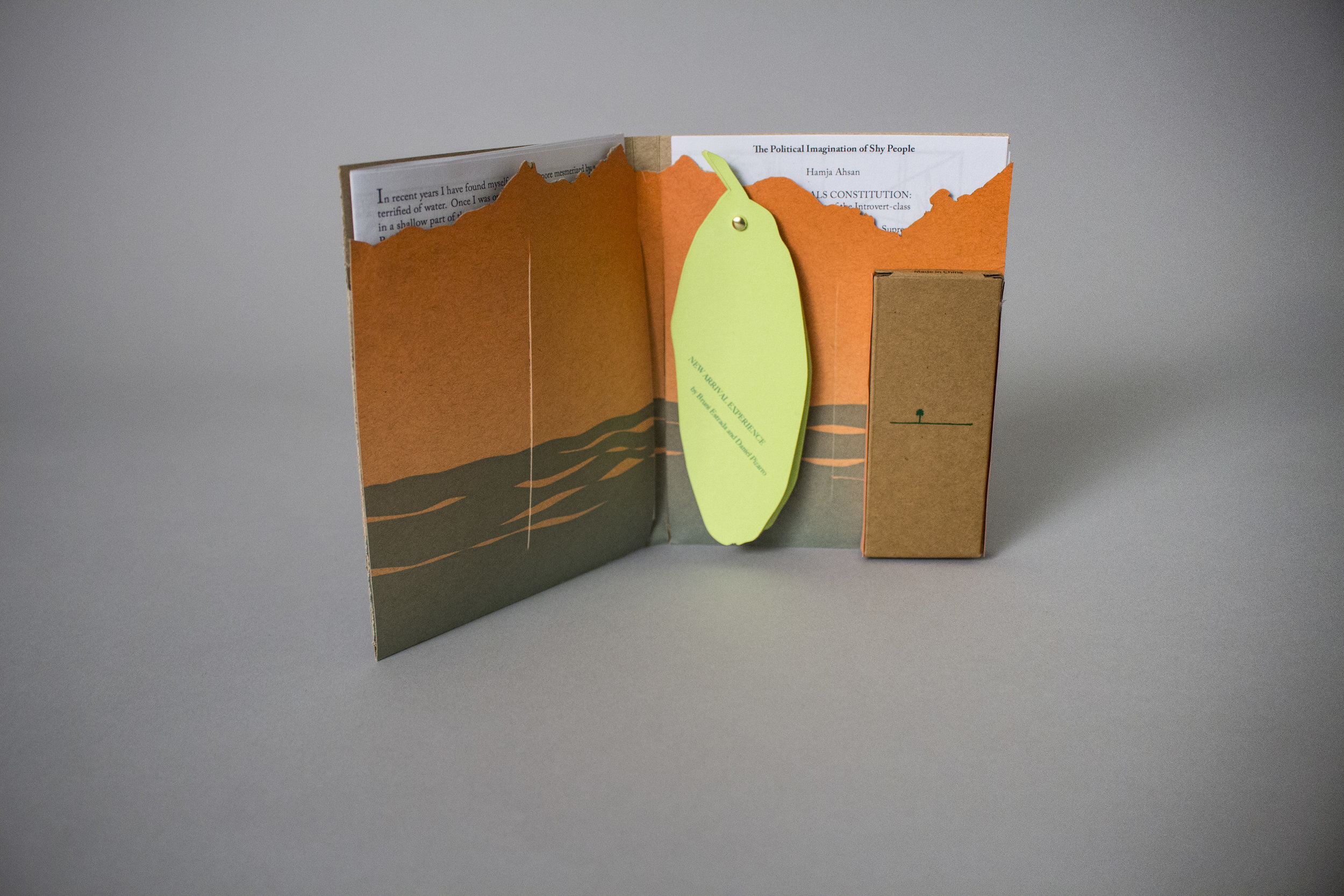

The Book of the Homeless

5.5” x 4.25”

About the contributors:

Hamja Ahsan is an activist and author of Shy Radicals.Bruni Estrada is an environmental activist and scholar.

Karl Orozco is an illustrator.

Daniel Pizarro is an activist and graphic designer.

Edith Wharton was an activist and author.

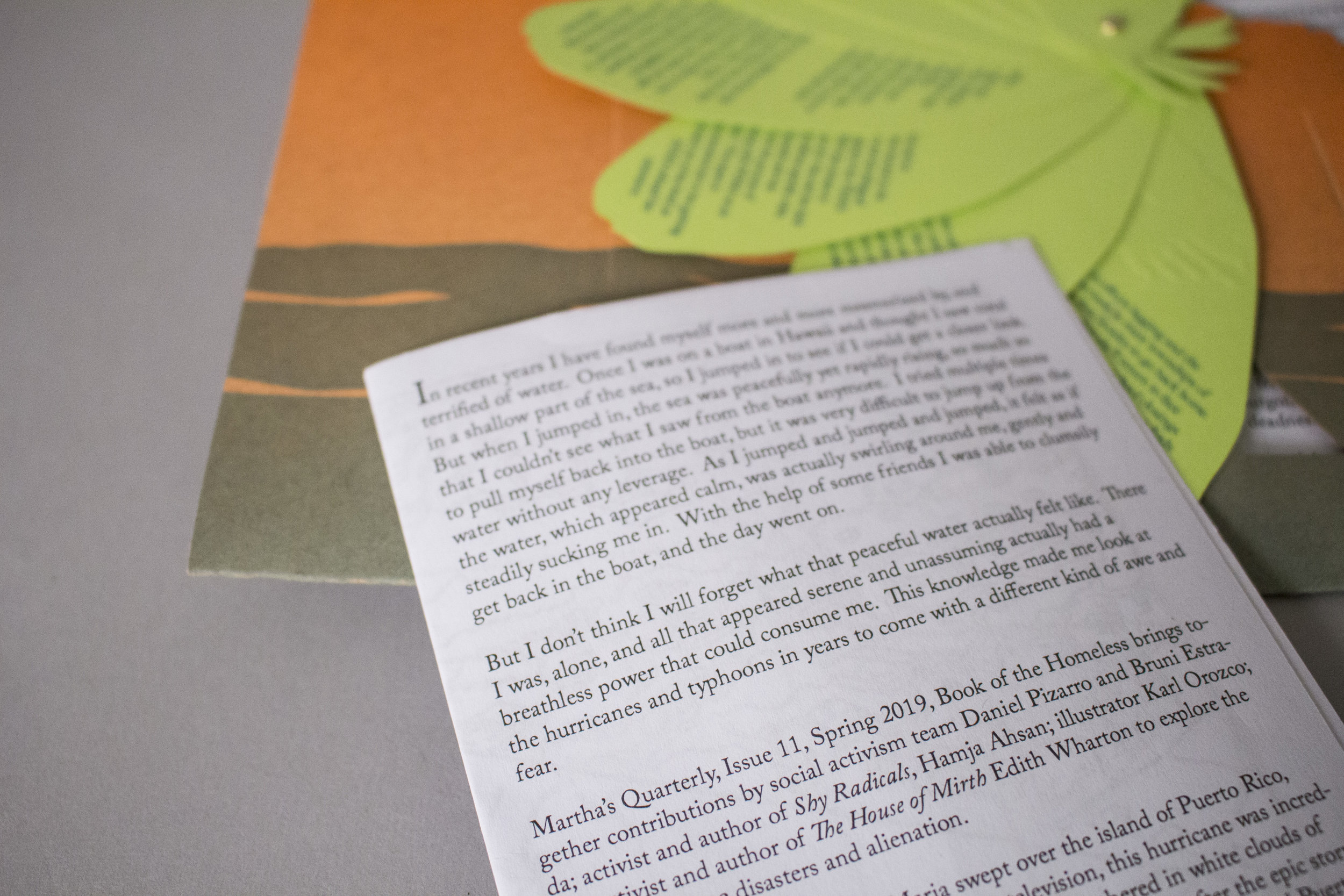

In recent years I have found myself more and more mesmerized by, and terrified of water. Once I was on a boat in Hawaii and thought I saw coral in a shallow part of the sea, so I jumped in to see if I could get a closer look. But when I jumped in, the sea was peacefully yet rapidly rising, so much so that I couldn’t see what I saw from the boat anymore. I tried multiple times to pull myself back into the boat, but it was very difficult to jump up from the water without any leverage. As I jumped and jumped and jumped, it felt as if the water, which appeared calm, was actually swirling around me, gently and steadily sucking me in. With the help of some friends I was able to clumsily get back in the boat, and the day went on.

But I don’t think I will forget what that peaceful water actually felt like. There I was, alone, and all that appeared serene and unassuming actually had a breathless power that could consume me. This knowledge made me look at the hurricanes and typhoons in years to come with a different kind of awe and fear.

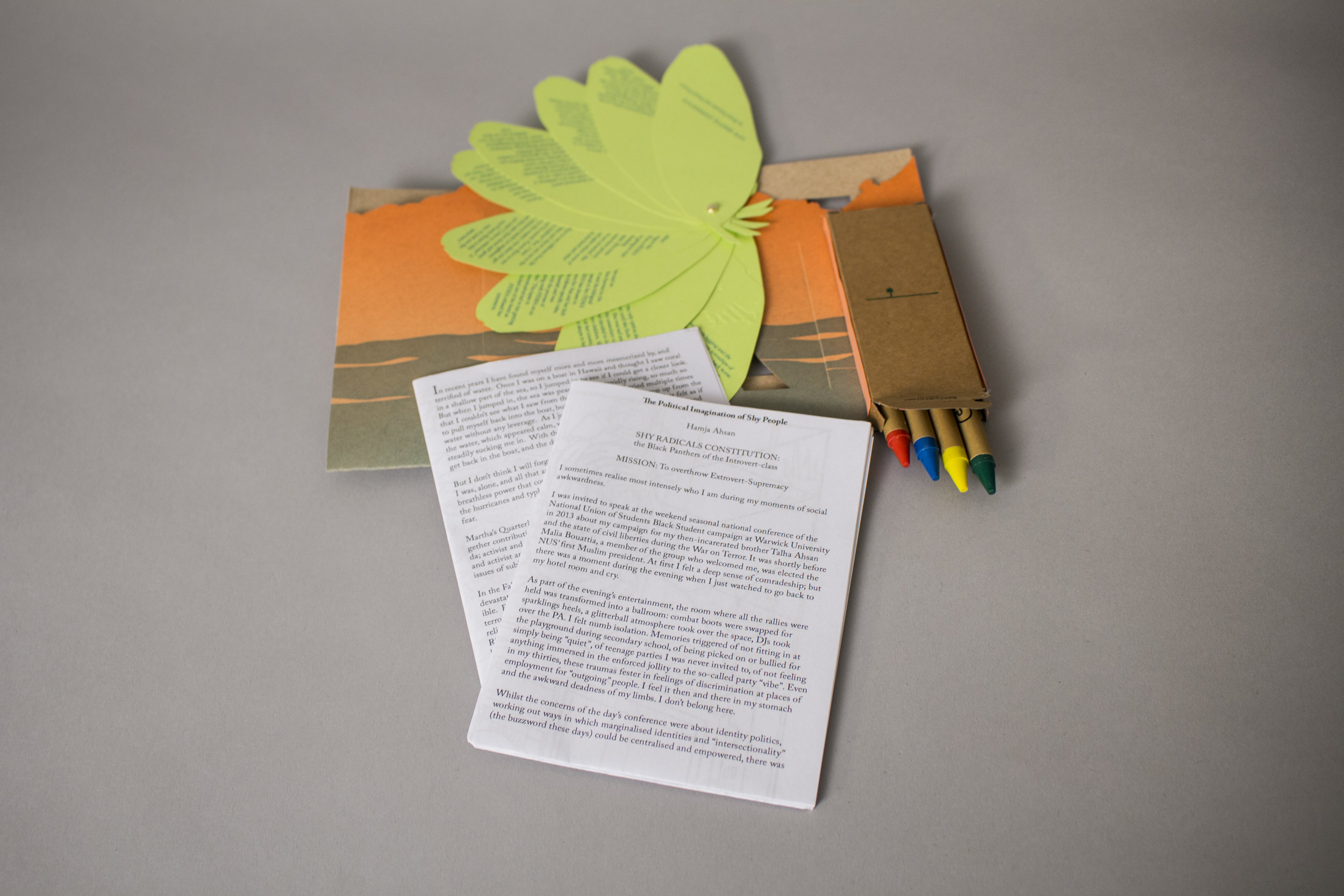

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 11, Spring 2019, Book of the Homeless brings together contributions by social activism team Daniel Pizarro and Bruni Estrada; activist and author of Shy Radicals, Hamja Ahsan; illustrator Karl Orozco; and activist and author of The House of Mirth Edith Wharton to explore the issues of sublime disasters and alienation.

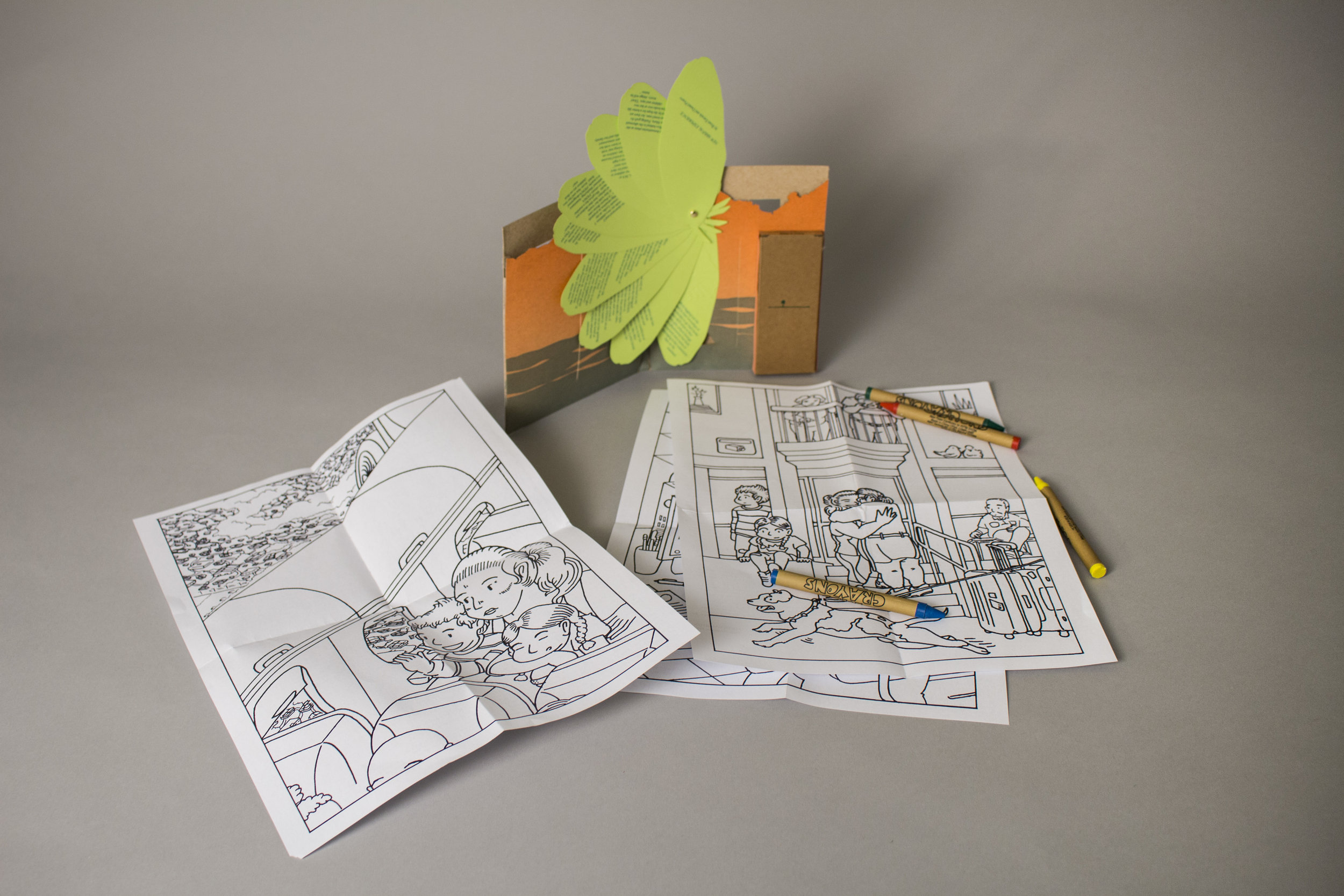

In the fall of 2017, Hurricane Maria swept over the island of Puerto Rico, devastating the island immeasurably. On television, this hurricane was incredible. Puerto Rico was but a freckle in the sea, smothered in white clouds of terror. There were 3,057 fatalities; today, more than a year after the epic storm, relief has barely rejuvenated the former infrastructure that supported Puerto Rican life. Most people witnessing the storm through a screen do not tangibly know the emotional distress of displacement and bureaucracy that has affected thousands of Puerto Rican lives. So, Passenger Pigeon Press invited Bruni Estrada, an environmental scholar, and Daniel Pizzaro, a graphic designer, who have been working on climate change and its intersection with race and displacement in Puerto Rico to inform our public of the common realities that many of Hurricane Maria’s victims face. Reading the story by fanning apart the palm tree, the reader learns of Ana and her two children and how they have been forced into homelessness in their own home.

But, now knowing this, what can a single person possibly do?

In America we don’t always think of the homeless of WWI, but after the war an estimated 200,000 Belgian refugees fled to France. In Paris, the writer Edith Wharton was a volunteer at the American Hostel for Refugees, where in just a year the charity had assisted 9,300 people. As the hostel dawned on its second year, with the usual worry of zero funding, Ms. Wharton rallied her colleagues across the arts to compile a book of poetry, literature, and art. This book, which this Martha’s Quarterly is named after, was called The Book of the Homeless, and all of the proceeds from its sales would go towards the funding of a second year of operations at the American Hostel. Included in this issue is Ms. Wharton’s preface to the anthology, where she illustrates the dire circumstances of the people newly displaced by WWI and the purpose of her book.

I admire that Ms. Wharton’s activism is through her presence and active participation in the hostel. Then, when she needs to extend to folks who cannot be present, she does so through art. In this way, social justice presents itself through an individualized-- and maybe lonely– process of reflection and absorption of intimate literature. In this way, The Book of the Homeless created space for contemplation while being an active help to those on the frontlines of war relief.

In the last three years or so, populist activism has spread through social media and tribalist gatherings, all of which has been more amplified as people cut and paste, post, retweet memes, selfies, and hashtags that align their beliefs with one camp or another, squeezing out room for nuance and contradiction. This is why when I read Hamja Ahsan’s sharp debut book Shy Radicals, I found it refreshing and insightful. His book satirically imagines a movement of people and a transformation of the world led by folks who are introverts-- or shy. He advocates for 24-hour access of art and libraries, so that folks can take culture in deeply and quietly. This issue of Martha’s Quarterly includes a reflection that Mr. Ahsan wrote before the manifestation of Shy Radicals: in this writing he sets up a strong case for the urgency of solitude after having attended an activist gathering at Warwick University. I think that Ms. Wharton could be considered a shy radical too, as demonstrated by her quiet yet assertive hard efforts at the hostel and her reaching outward through art.

The fourth component of this Martha’s Quarterly is an invitation for you to contemplate Ms. Estrada and Mr. Pizzaro’s narration of Ana’s hurricane story by coloring in thoughtful illustrations by Karl Orozco. After you open this introduction, Edith Wharton’s preface to Book of the Homeless and Hamja Ahsan’s The Political Imagination of Shy People, you will find Orozco’s drawings depicting the first three palm leaves of Ms. Estrada and Mr. Pizzaro’s story. Please, then, open up the enclosed crayons and color, color in between the lines, or all over. Color the people blue and green and the house in yellow. Color however you wish, but allow for the act of coloring to invite you into this house for the homeless as a shy radical.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief