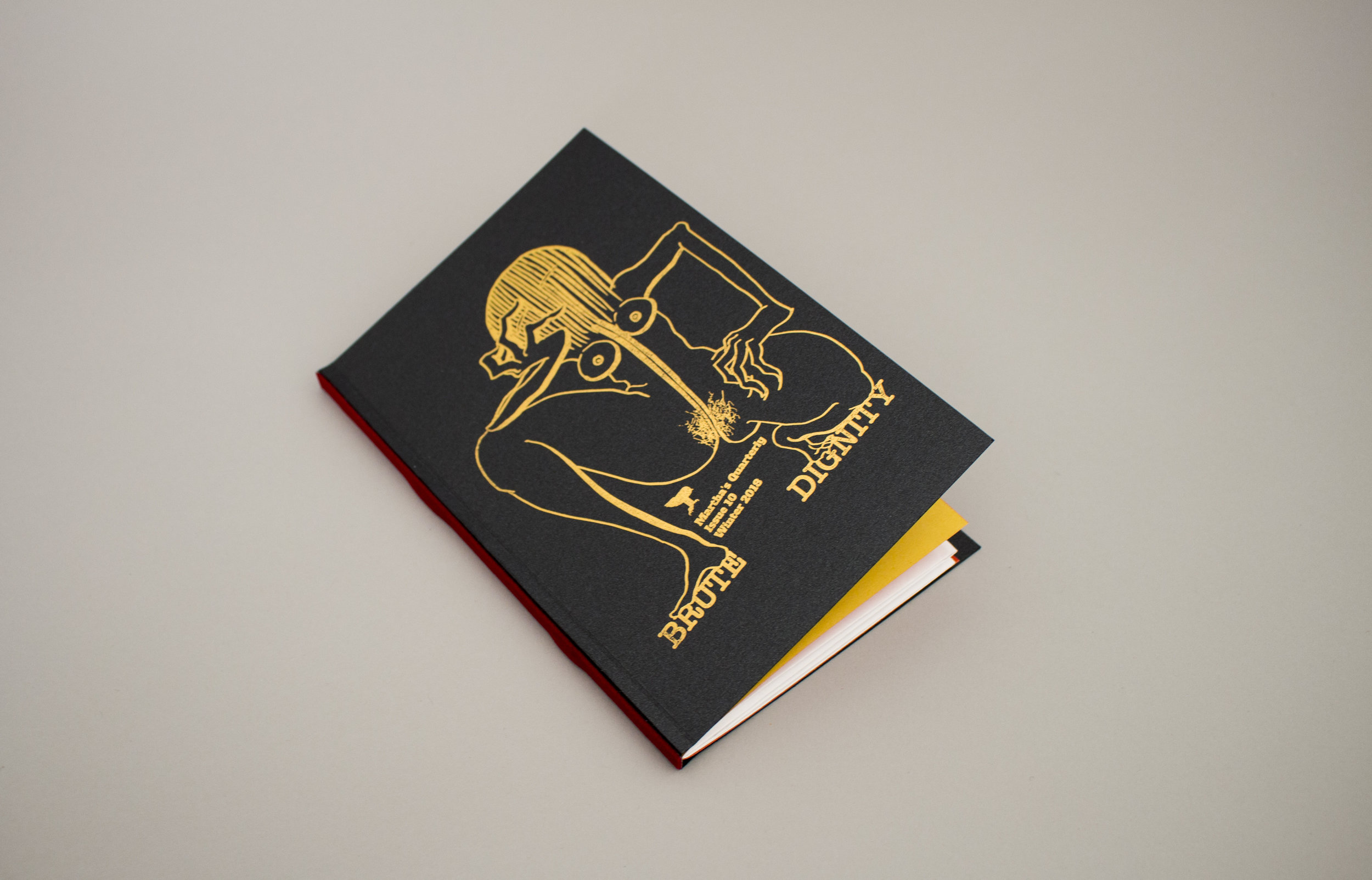

MQ 2018

Martha's Quarterly

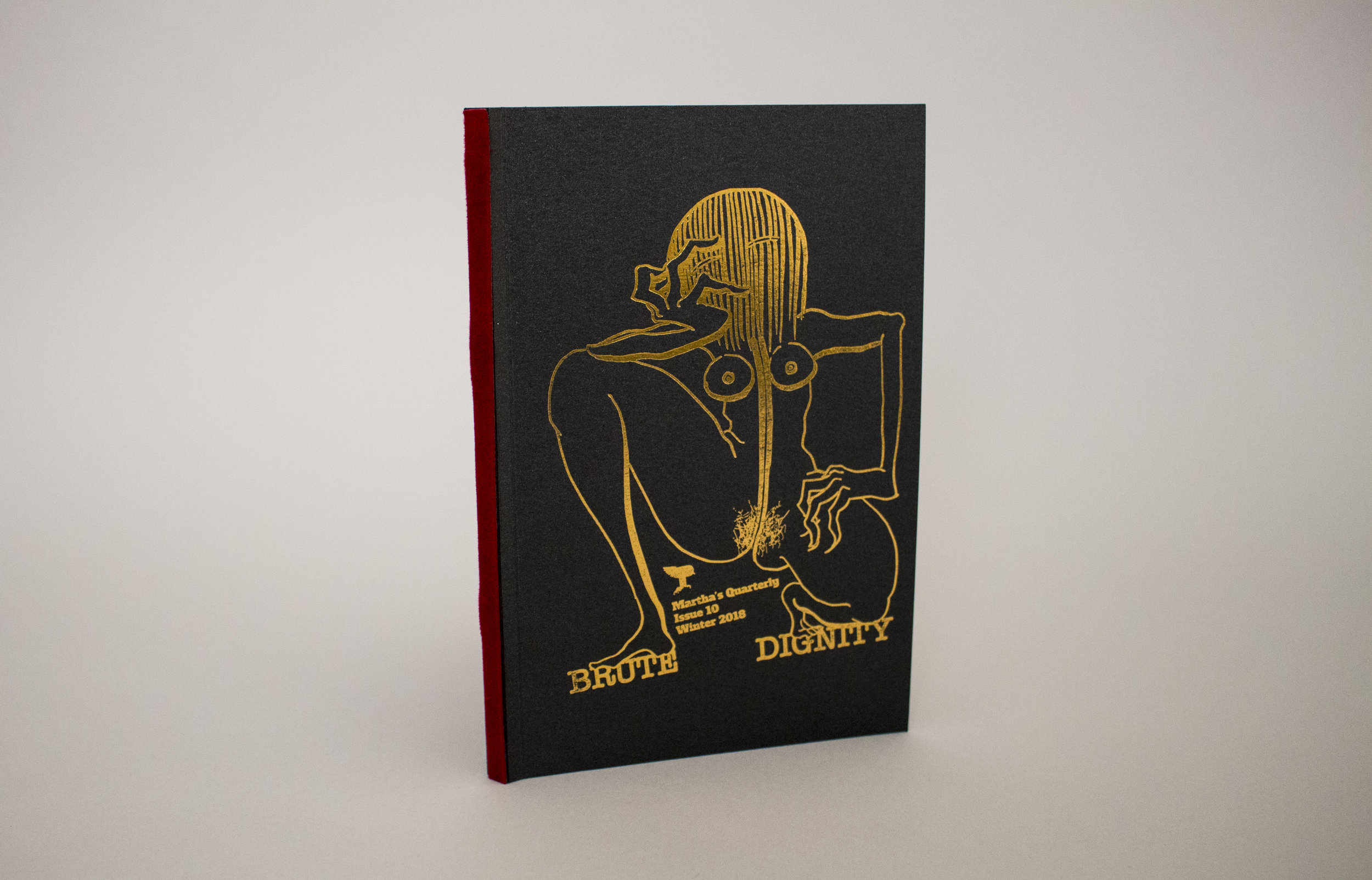

Issue 10

Winter 2018

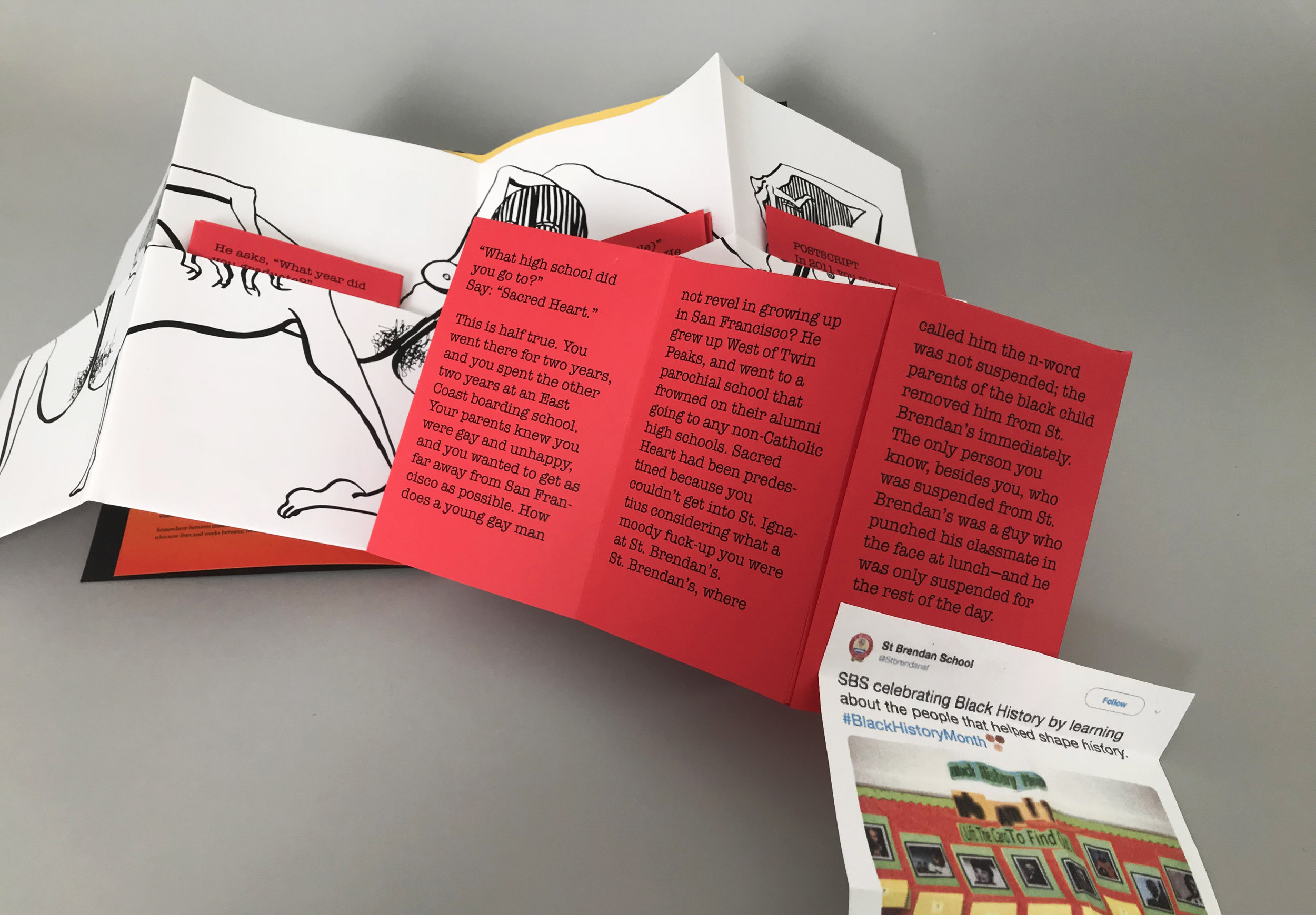

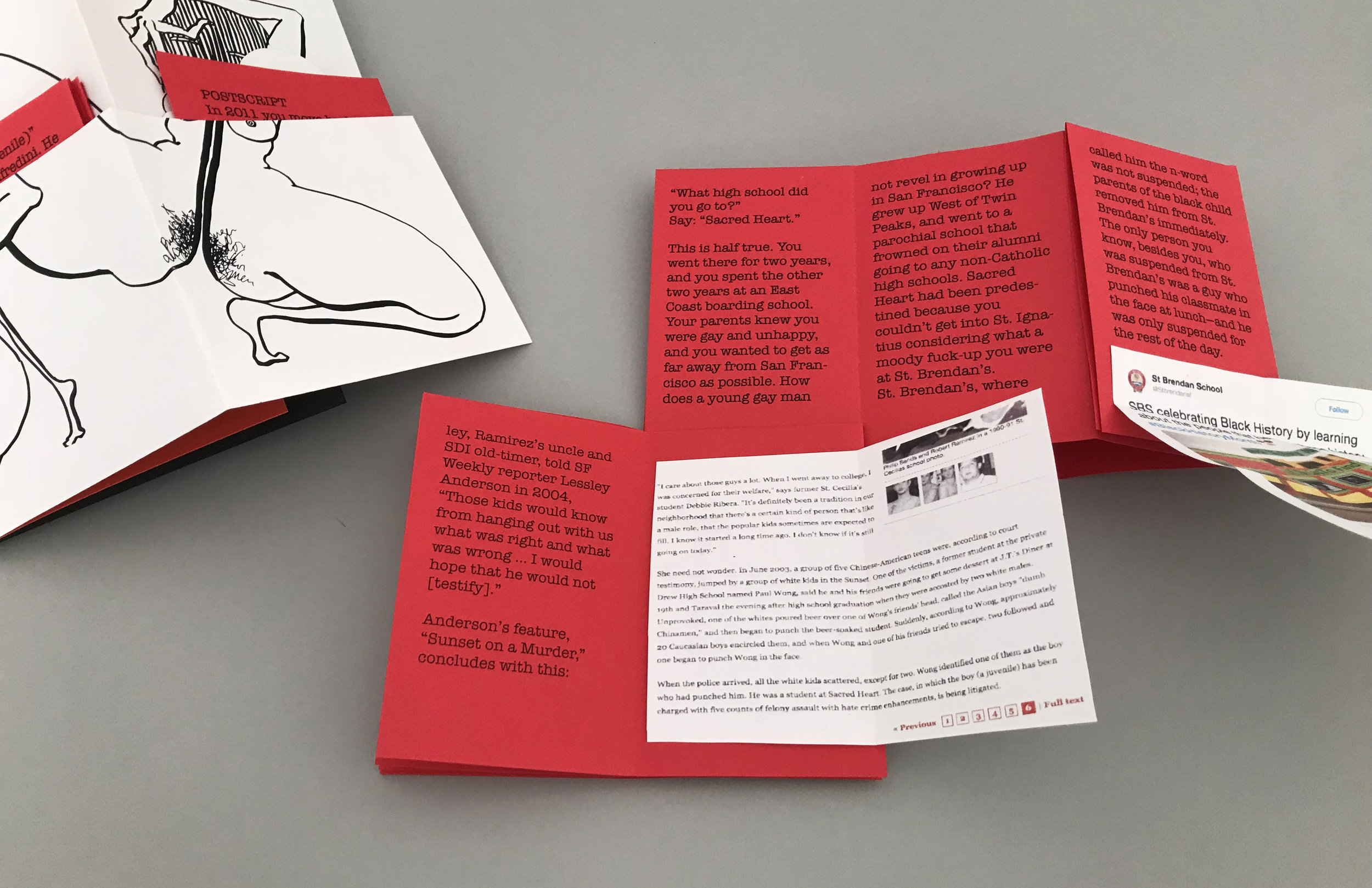

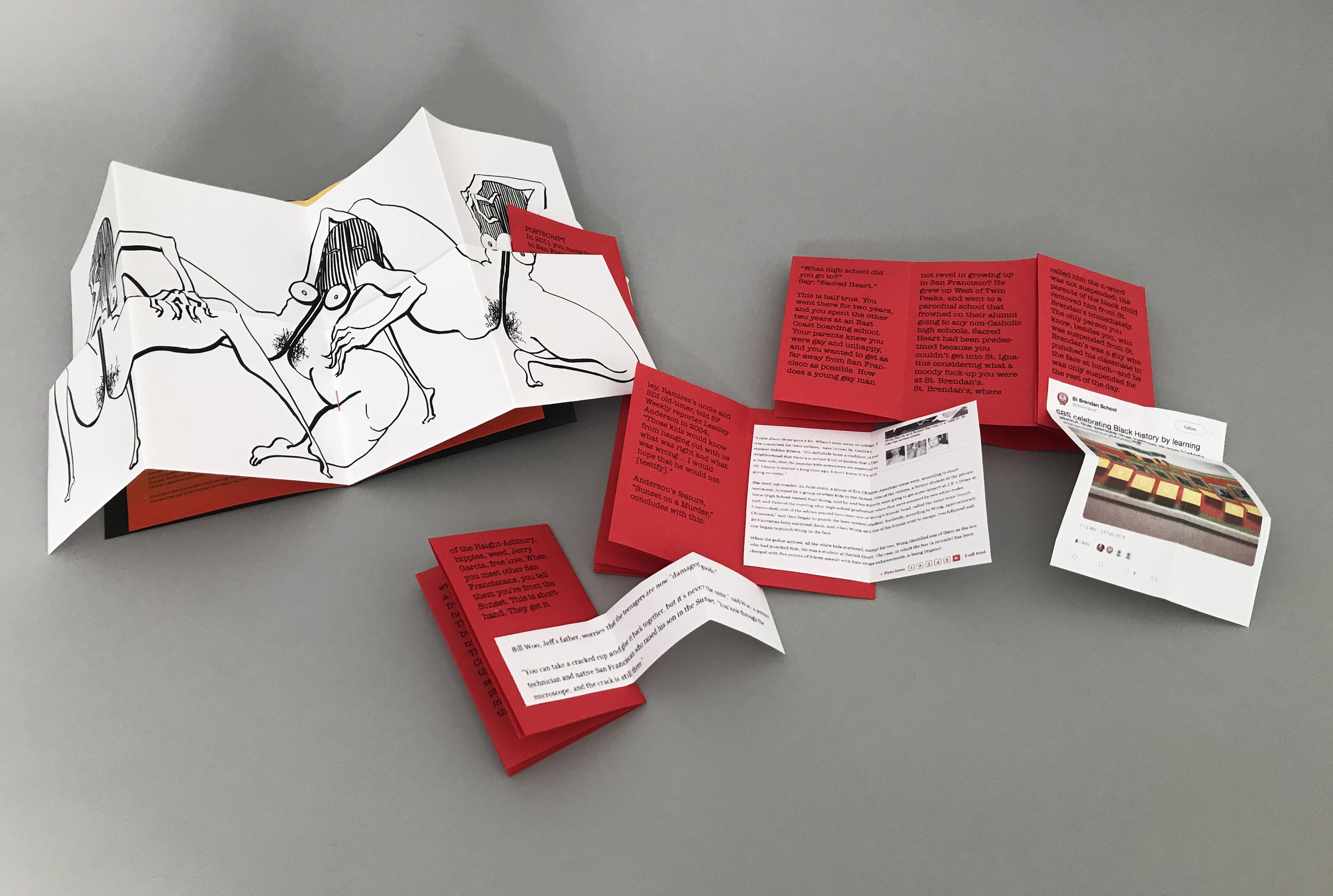

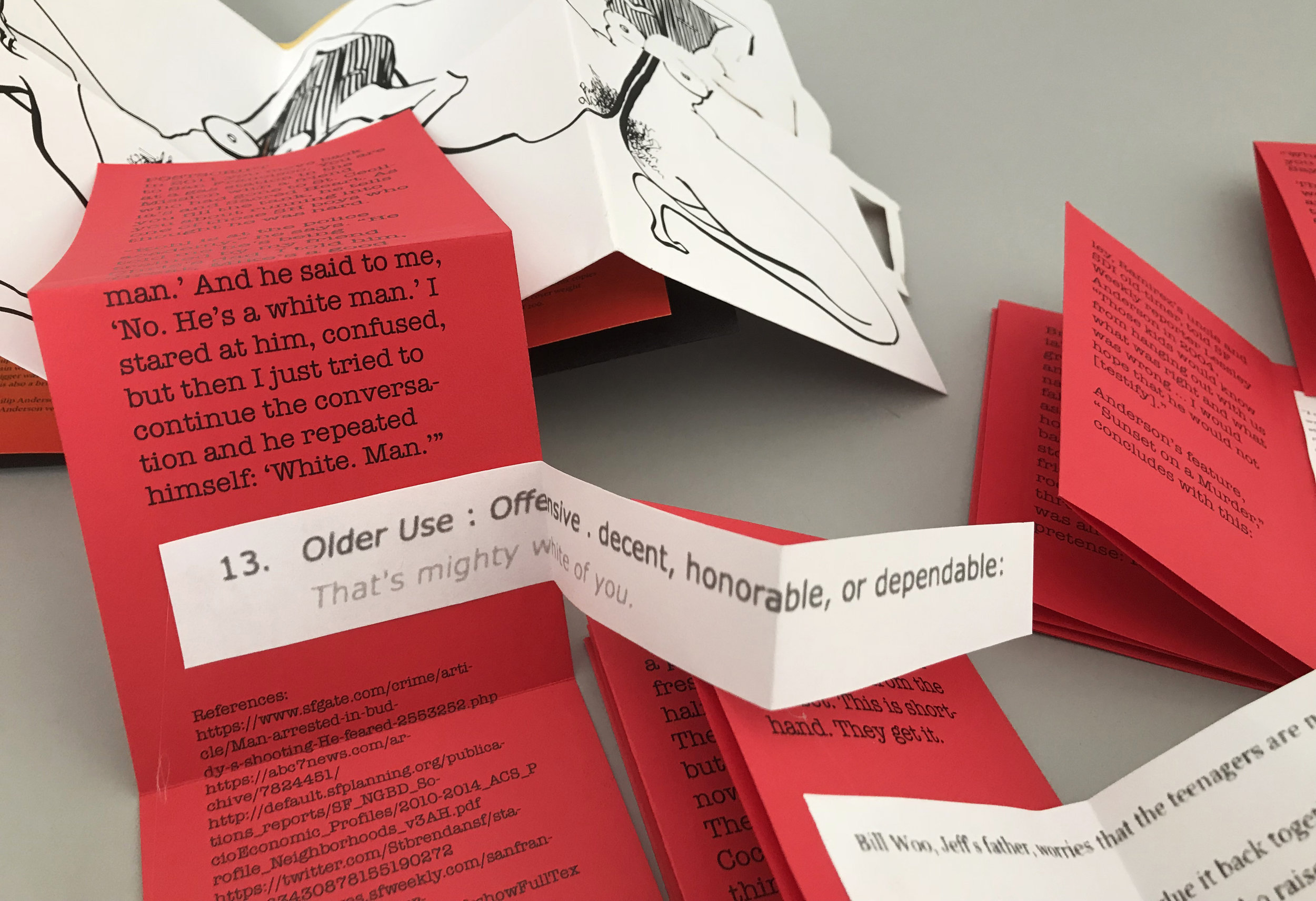

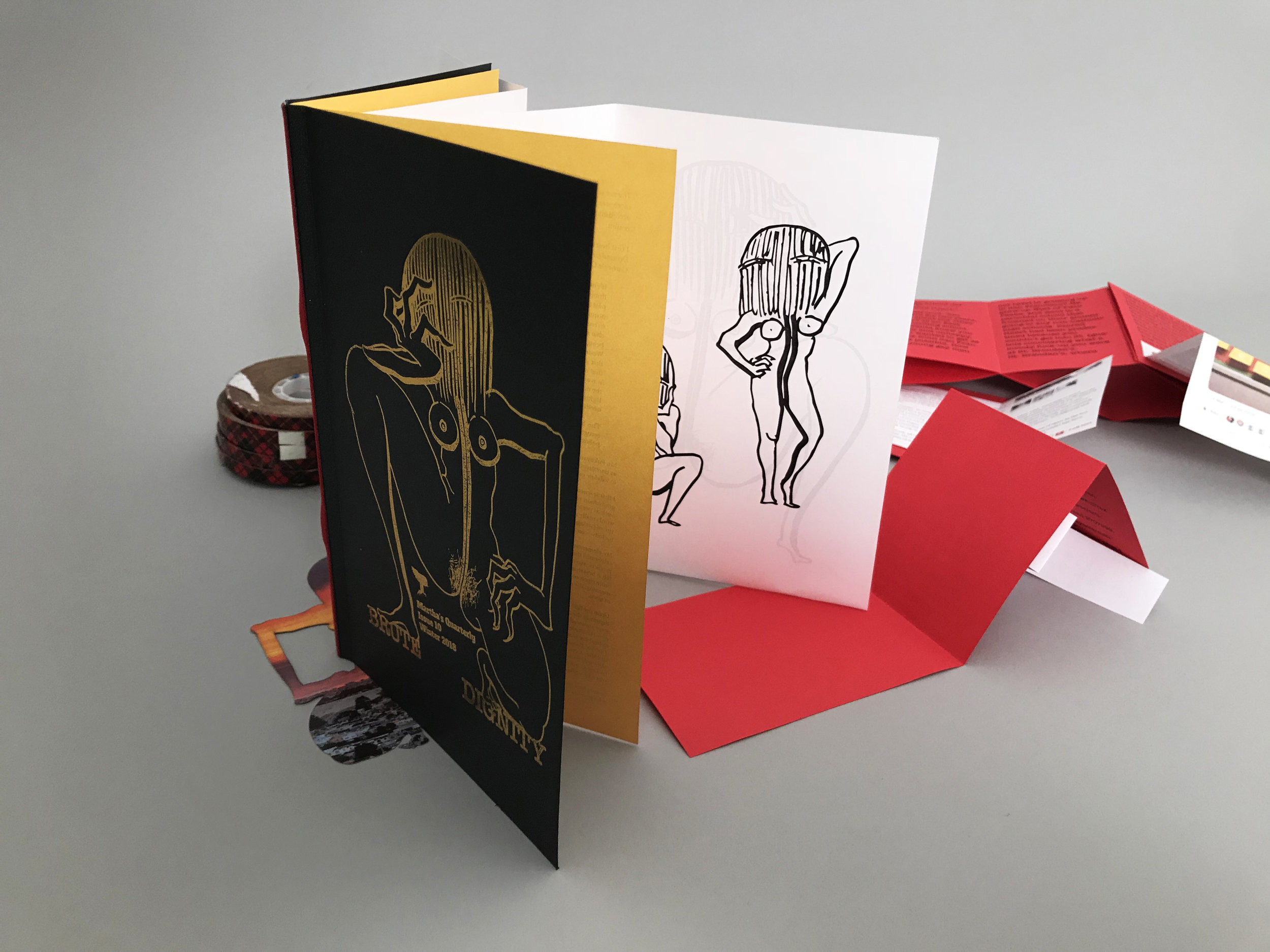

BRUTE DIGNITY

7” x 5”

About the contributors:

Philip Anderson is an MFA candidate and creative writing teaching fellow at Columbia University. He lives in New Haven with his partner and their two cats, Sherwood and Blue Ivan.Téa Chai Beer is a visual artist living in New York City. She is the Project Manager at Passenger Pigeon Press. She also has a cat named Minnow.

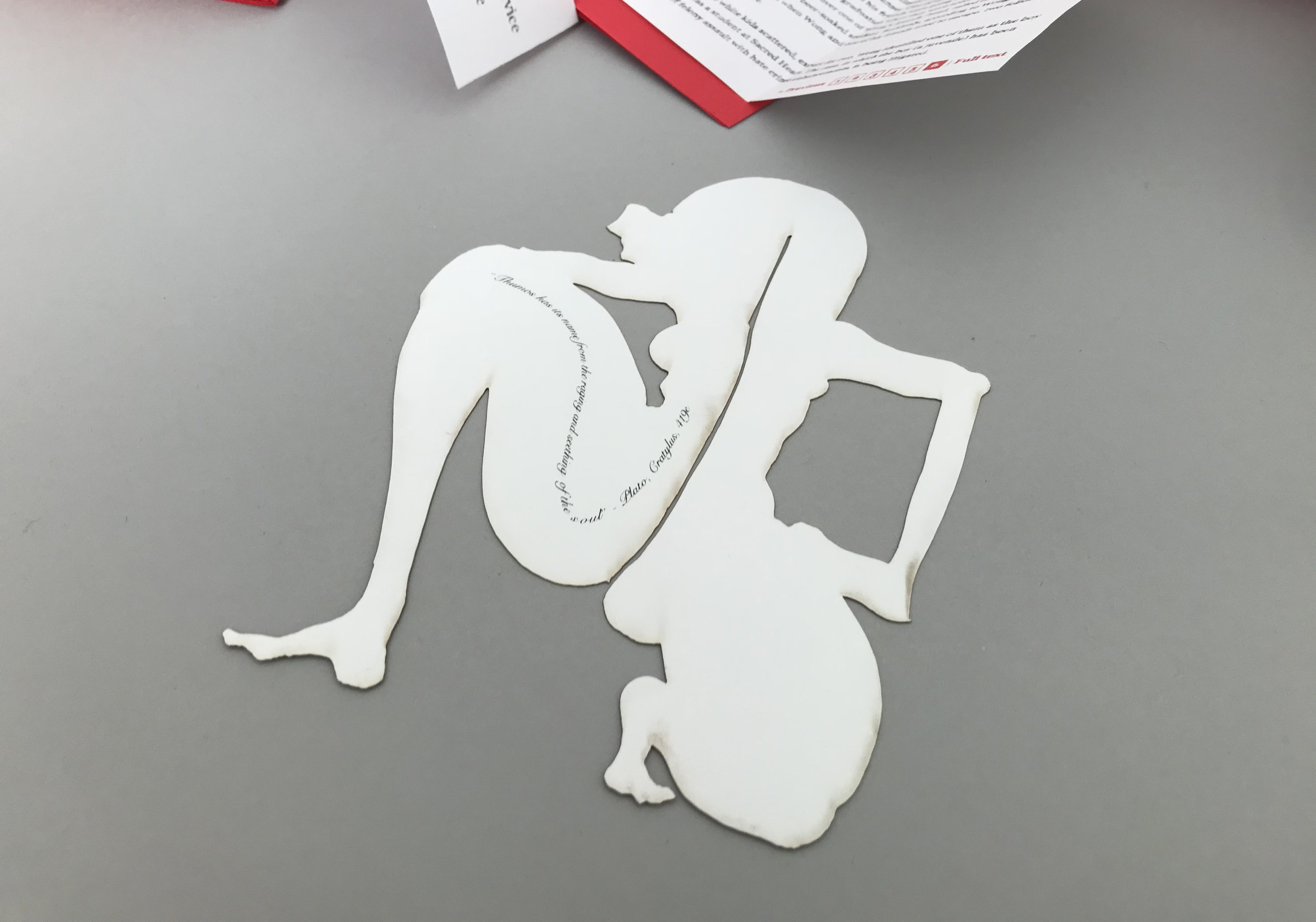

Thumos is a part of the soul where the “spirited” lives. This is the part of your soul that motivates you to be brave, to fight for what is right. This is the part of your soul that, according to Plato in the Republic, leads to higher truth and virtue when it is used with reason.

I first heard of thumos at last September at the Carnegie Council in New York. Francis Fukuyama was giving a lecture based on his latest book Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. He explained:

Identity I think begins with the psychological phenomenon that Plato labeled thumos. It's a Greek word that is usually translated as "spiritedness," but it's the part of the human psychology that the economists just don't get. They get acquisitiveness and they get rationality, but thumos is this desire for other people to recognize your internal worth or dignity, and I think it's a universal characteristic, particularly when you feel that you've got an inner self that is not being adequately recognized by the surrounding society. That's the part of it that in Western thought has developed over the last several hundred years into the way that we think about ourselves. We think that we have a deeply buried inner self that is authentic and is being suppressed by the society around us, and unlike wayward teenagers from time immemorial who are brought into compliance with the outward society, the modern idea is that actually that inner self is the true, legitimate one, and it's the outer society that's false, and it's the outer society that needs to change.

This becomes the basis for a lot of political movements because we want public recognition. We want other people to affirm our worth, and that has to be a political act. (1)

Mr. Fukuyama later cited the Arab Spring, the French Revolution, and Osama bin Laden as narratives where thumos resulted in acts and movements to affirm one’s identity and to validate one’s worth and dignity.

I first learned the word dignity when I was graduating from the fifth grade as part of a graduation song. I had no idea what it meant, but it was attached by notes to other words such as perseverance, integrity, and honor– and to be honest, I wasn’t sure what those words really meant either. What I did know, at age 11, was that singing this song was a rite of passage, and whatever happened after fifth grade, I would do so with this new melody--an anthem for a new me: a new leader in the world and a brave woman.

My elementary school was utopic: it was a top tier public school in San Francisco that celebrated the ethnic and religious backgrounds of all students through multiple lessons, projects, assemblies, and festivities year after year. But after the fifth grade, my parents felt it best that I continue my education in a Catholic school where the academics were more rigorous; it wasn’t as expensive as an independent secular school, and it was safe--meaning, the school’s population didn’t draw from the neighborhoods from another side of town.

Upon the first day of Catholic school--my uniform uncomfortably perfect– I saw dignity in the church. The pastor welcomed all into the sanctuary, and new beginnings were anointed with the assistance of the most perfect looking young men in robes; my new classmates and altar boys. Soon, when we returned to class, it was not uncommon to hear the words nigger or faggot used to tease or separate some people from others. Thumos’ flame burned bright when some students informed others that they were fat or ugly. These slurs, along with clear-cut social groupings, were normal and obviously painful the lower you were on the social food chain where thumos’ flame still flickered. But the young man who called the other man a nigger was a dignified man when he walked his sister home. This dignified young man is also a brute.

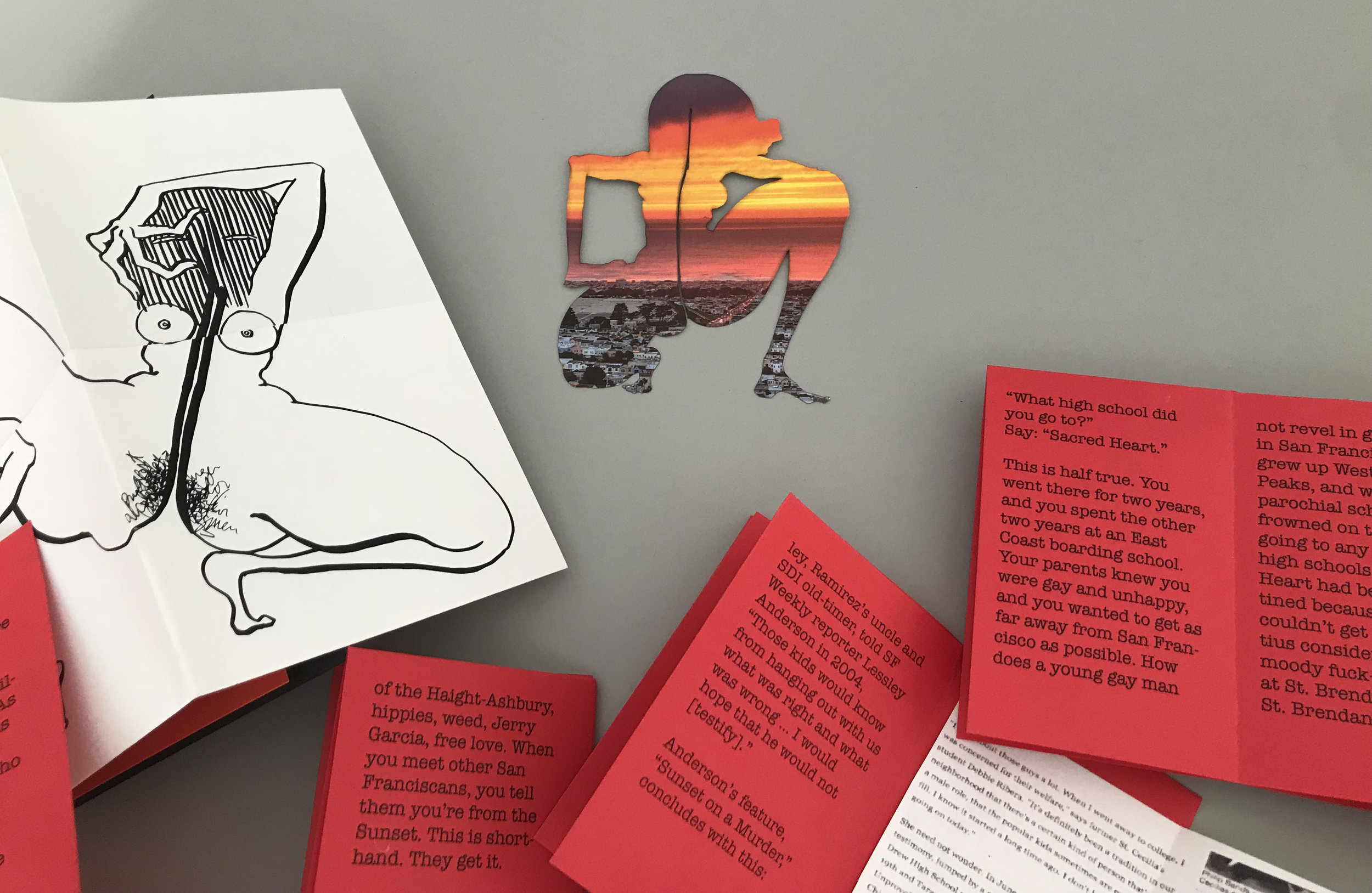

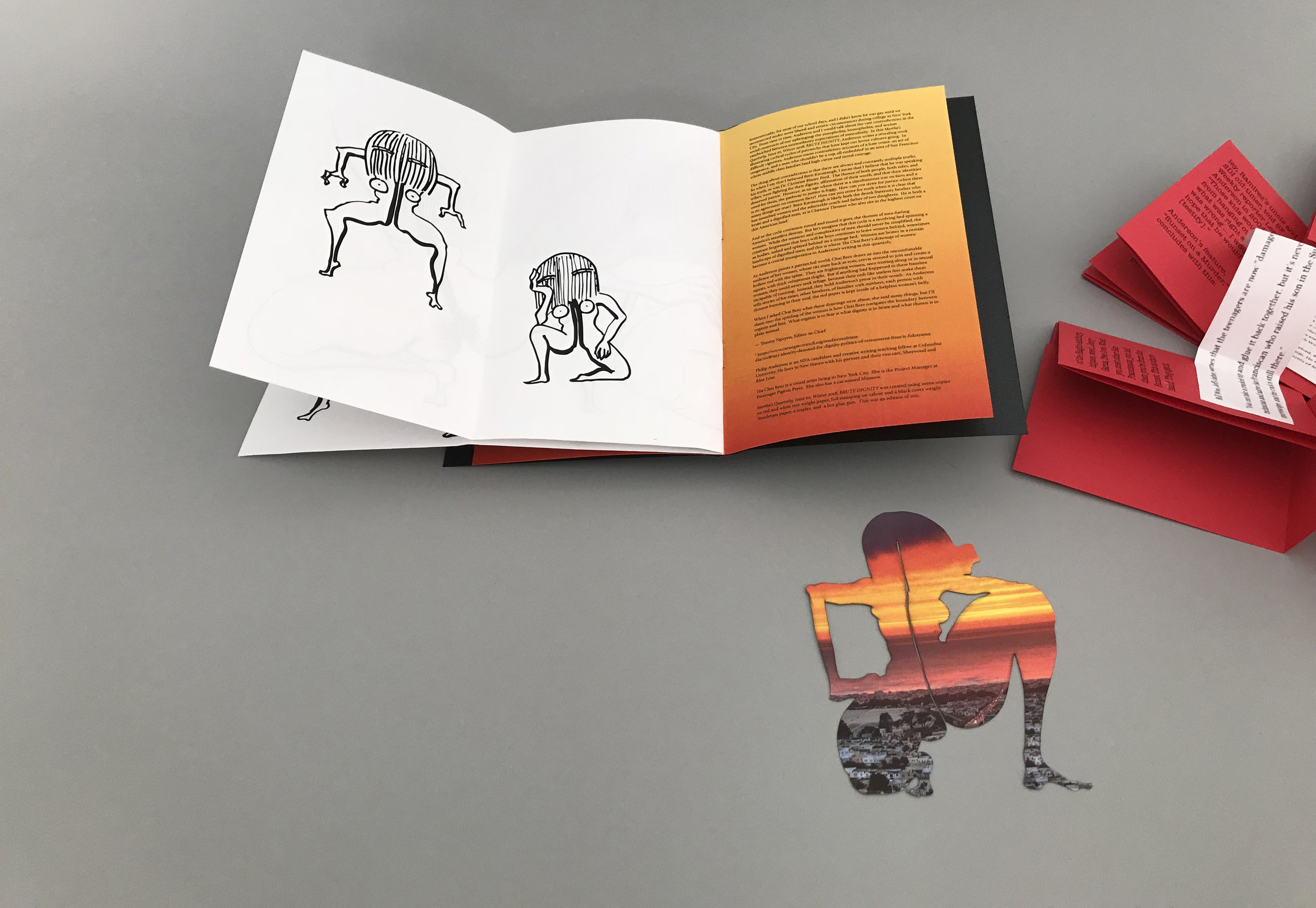

Somewhere between middle school and high school, I met Philip Anderson, a writer who now lives and works between New Haven and New York. Anderson veiled his homosexuality for most of our school days, and I didn’t know he was gay until we reconnected under more liberal and artistic circumstances during college in New York City. From time to time, Anderson and I would talk about the vast contradictions in the social constructs of our upbringing: the xenophobia, homophobia, and sexism sandwiched between extraordinary expectations of masculinity. In this Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 10, Winter 2018: BRUTE DIGNITY, Anderson writes a revealing work illustrating cyclical cycles of patriarchy that have kept our home cultures going. In difficult vignettes, Anderson traces contradictory accounts of a hate crime, an act of vengeance, and a man who shouldn’t be a cop, all embedded in an area of San Francisco where middle class families laud high virtue and moral courage.

The thing about contradictions is that there are always and constantly multiple truths. So when I say that I believed Brett Kavanaugh, I mean that I believe that he was speaking his truth, as was Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. The thumos of both people, both sides, and tribes, were fighting for their dignity, affirmation of their worth, and that their identities deserved justice. However, in an age where there is a simultaneous war on facts and a need for them, the pathway to justice is foggy. How can you strive for justice when there is no agreement on common facts? How can you strive for truth when it is clear that many things are true? Brett Kavanaugh is likely both the drunk fraternity brother who has assaulted women and the admirable coach and father of two daughters. He is both a brute and a dignified man, as is Clarence Thomas who also sits in the highest court on this American land.

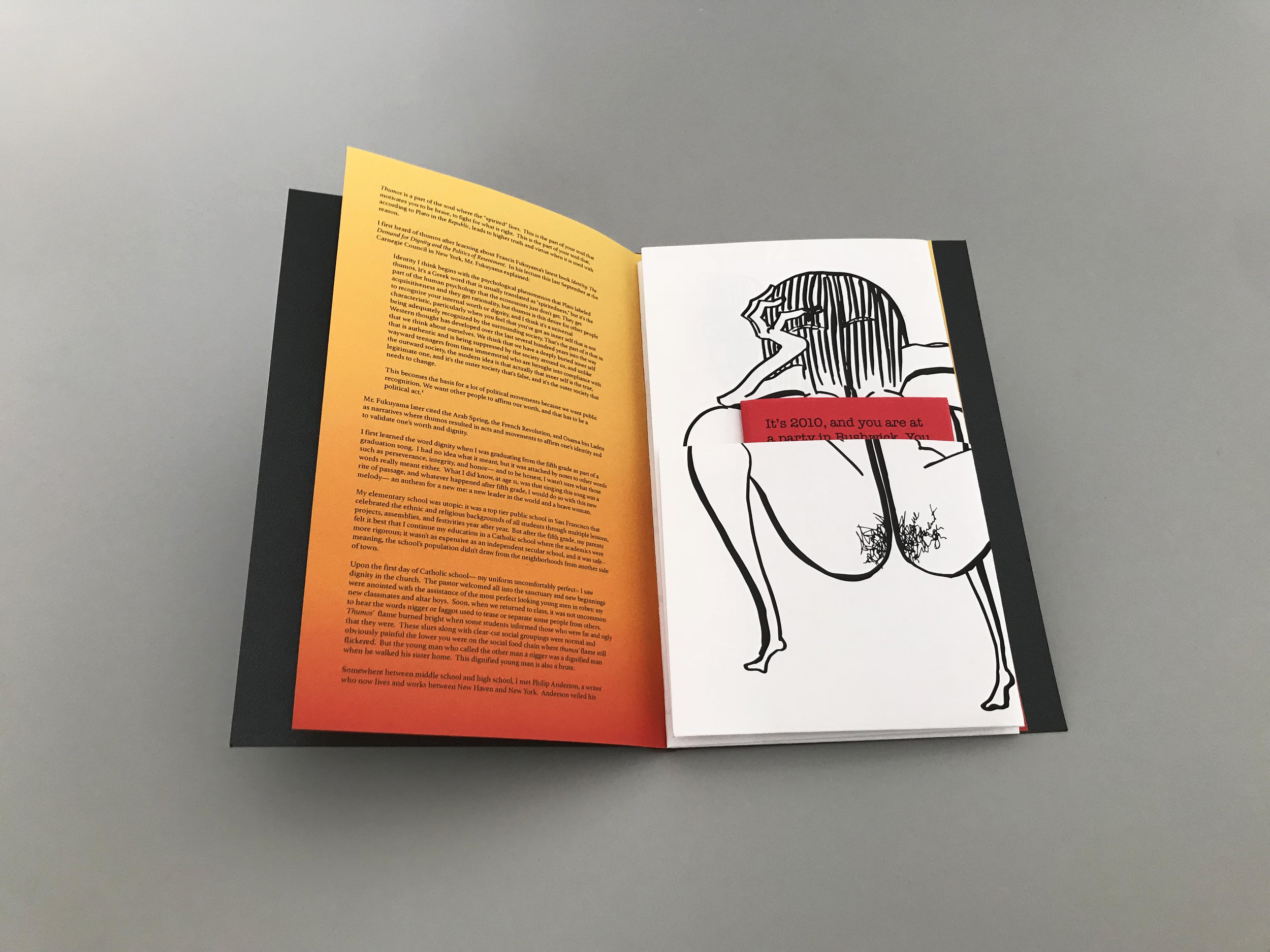

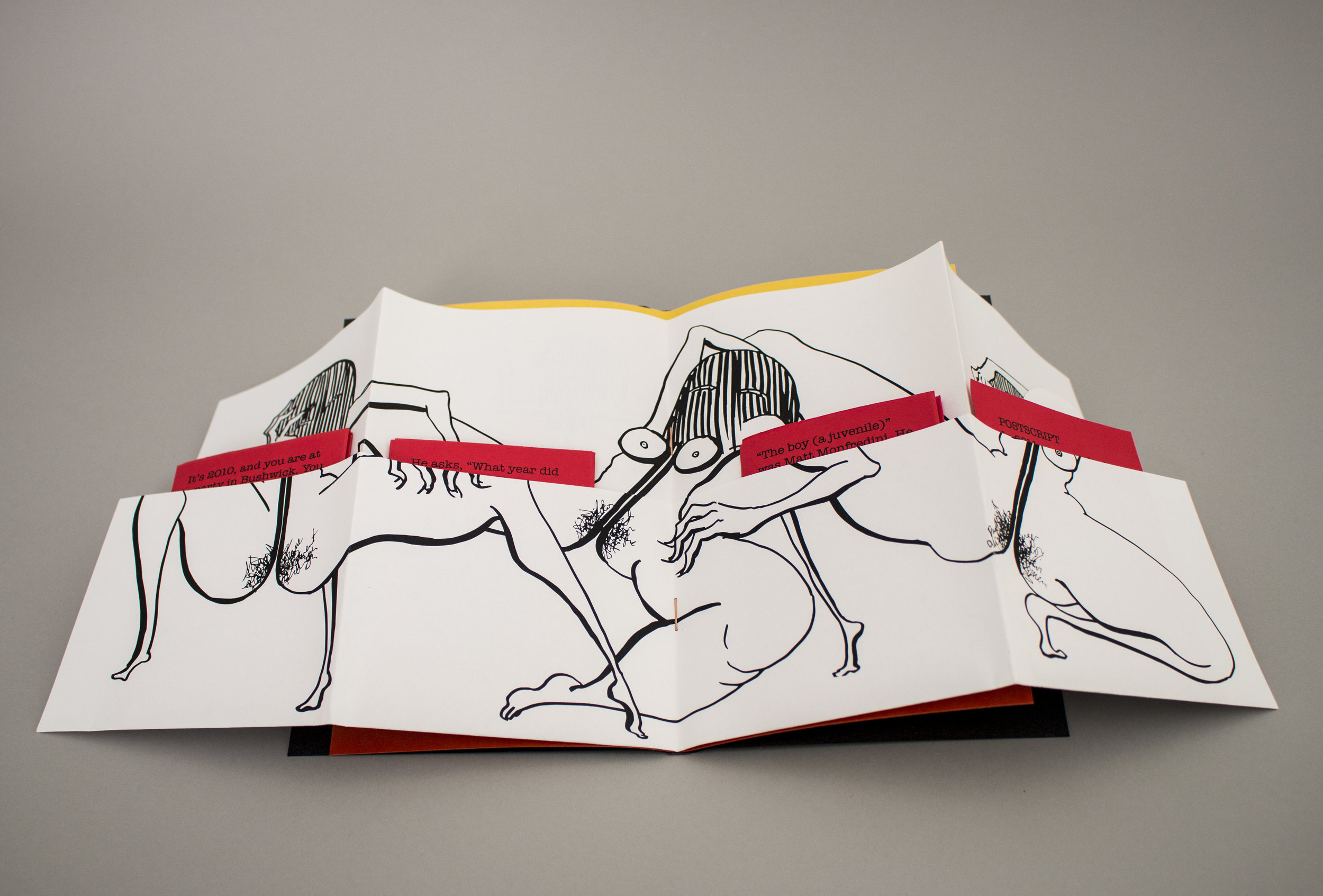

And so the cycle continues: round and round it goes, the thumos of men fueling America’s manifest destiny. But let’s imagine that this cycle is a revolving bed spinning a woman. While the nuances and complexities of men should never be simplified, the constant forgiveness that boys will be boys continues to leave women behind, sometimes as bodies, naked and splayed behind on a strange bed. Women are brutes in a certain landscape of dignified men; and this is where Téa Chai Beer’s drawings of women become a crucial juxtaposition to Anderson’s writing in this quarterly.

As Anderson paints a patriarchal world, Chai Beer draws us into the uncomfortable embrace of her women, whose tits stare back as eyes, cervix severed to join and create a hollow rod with the spine. They are frightening women, seen trotting along or in sexual squats, with thick voluptuous thighs. But if anything bad happened to these banshee women, they could never seek refuge, because their nub-like useless feet make them incapable of running. Instead, they hold Anderson’s prose in their womb. As Anderson tells stories of his sister, other brothers, of families with mothers, each person with thumos burning in their soul, the red paper is kept inside of a helpless woman’s belly.

When I asked Chai Beer what these drawings were about, she said many things, but I’ll share one: the spittling of the woman is how Chai Beer navigates the boundary between orgasm and fear. What orgasm is to fear is what dignity is to brute and what thumos is to plain animal.

Martha's Quarterly

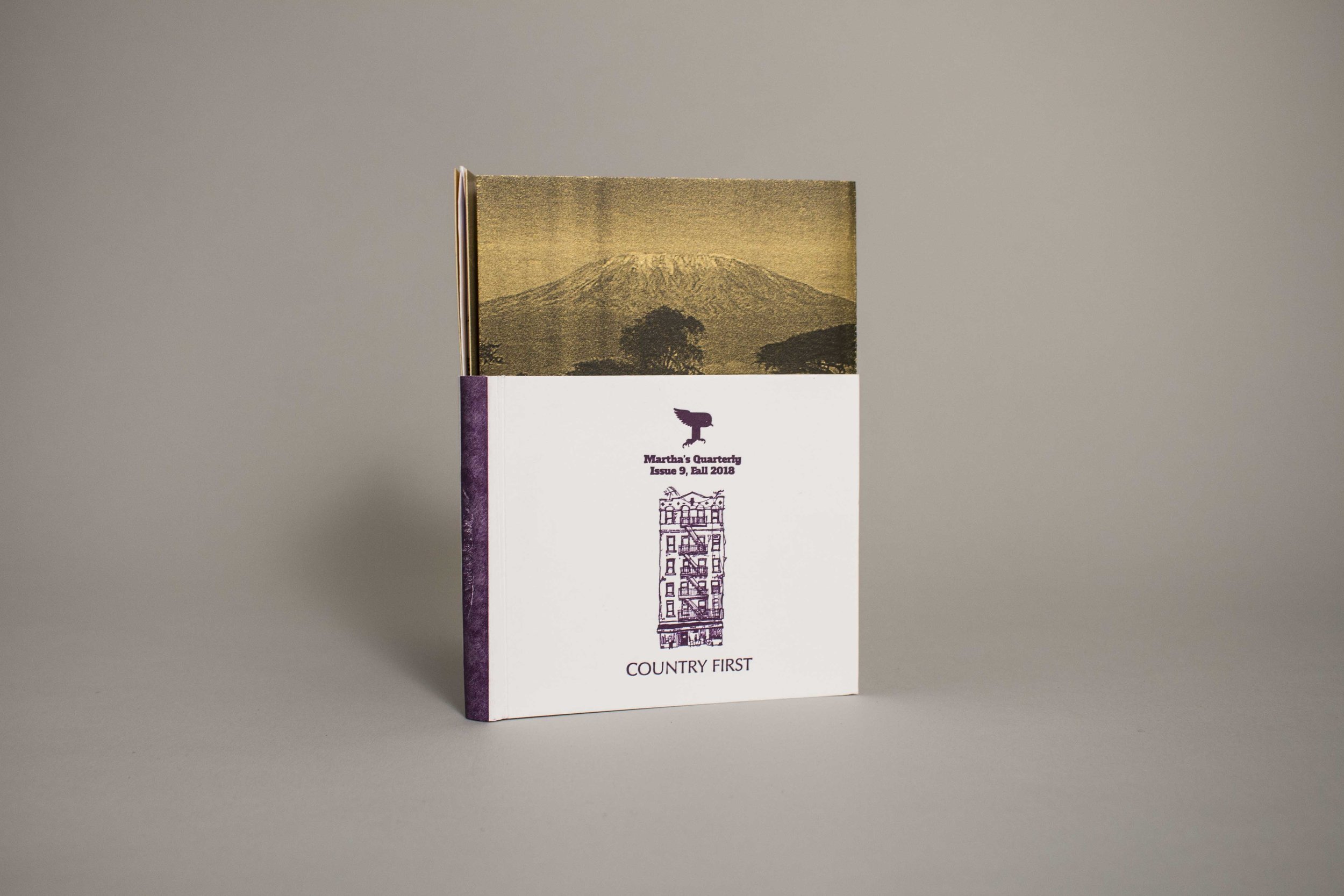

Issue 9

Fall 2018

Country First

6.25” x 4.75”

About the contributors:

Mei Lum is the 5th generation owner of her family’s 93-year-old porcelain ware business and the oldest operating store in NYC's Chinatown, Wing on Wo & Co. (W.O.W.). In light of Chinatown's rapid cultural displacement, Mei established a community initiative, the W.O.W. Project, out of a desire to amplify community voices and stories through art, culture and activism.

Rakhee Kewada is a Zimbabwean geographer currently studying the political economy of Tanzania's cotton textile industry. She is a PhD Candidate in Geography at the Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY) and teaches Urban Studies at Hunter College. Her art practice is research-based and collaborative. Committed to engaging the politics of knowledge production and dissemination, she has developed a series of participatory public art projects. She is currently exploring film and photography as a means of presenting her research on trade and commodity flows between China and Africa.

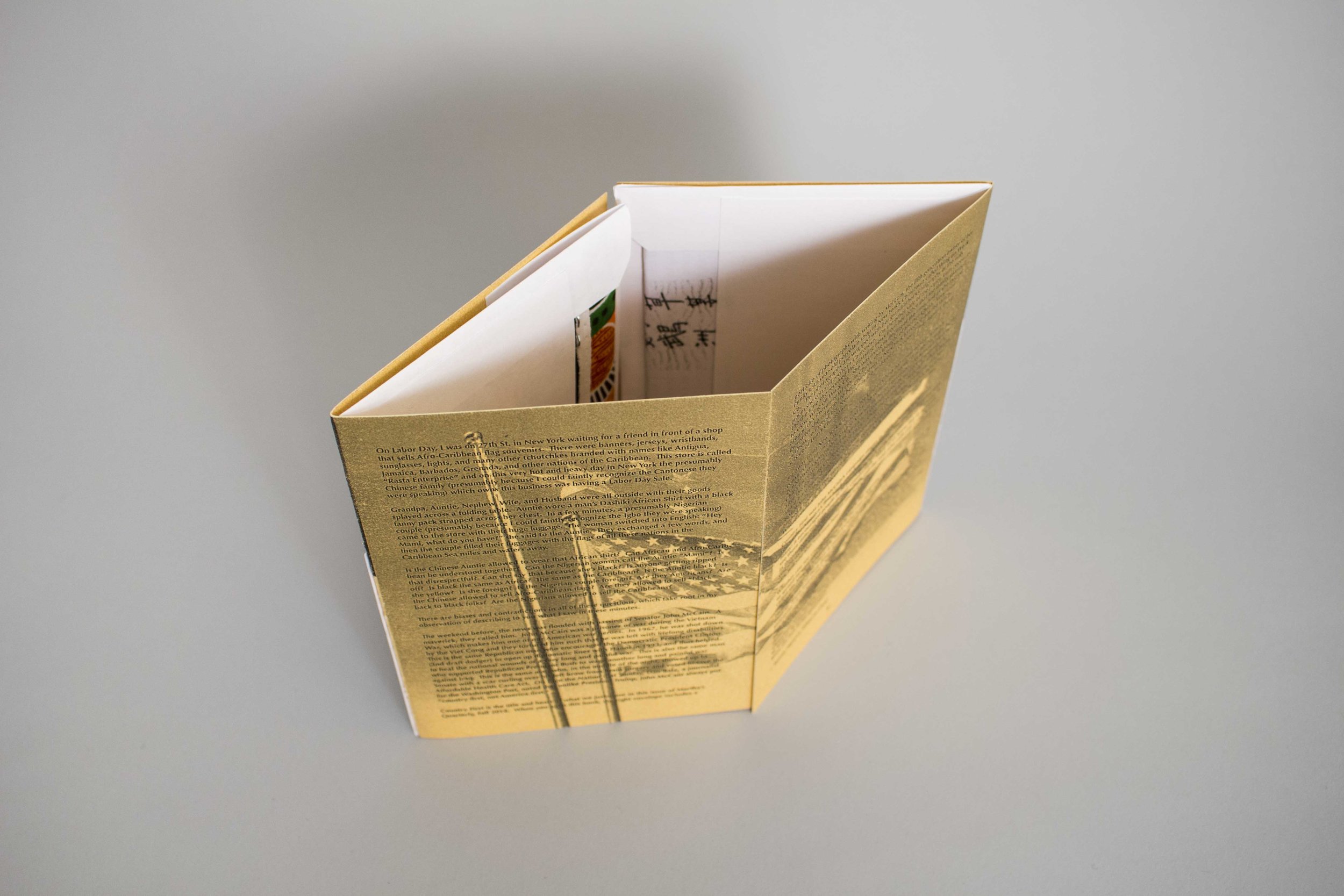

On Labor Day, I was on 27th St. in New York waiting for a friend in front of a shop that sells Afro-Caribbean flag souvenirs. There were banners, jerseys, wristbands, sunglasses, lights, and many other tchotchkes branded with names like Antigua, Jamaica, Barbados, Grenada, and other nations of the Caribbean. This store is called “Rasta Enterprise” and on this very hot and heavy day in New York the presumably Chinese family (presumably because I could faintly recognize the Cantonese they were speaking) which owns this business was having a Labor Day Sale.

Grandpa, Auntie, Nephew, Wife, and Husband were all outside with their goods splayed across a folding table. Auntie wore a man’s Dashiki African Shirt with a black fanny pack strapped across her chest. In a few minutes, a presumably Nigerian couple (presumably because I could faintly recognize the Igbo they were speaking) came to the store with their huge luggage. The woman switched into English: “Hey Mami, what do you have?” she said to the Auntie. They exchanged a few words, and then the couple filled their luggages with the flags of all these nations in the Caribbean Sea miles and waters away.

Is the Chinese Auntie allowed to wear that African shirt? Can African and Afro-Caribbean be understood together? Can the Nigerian woman call the Auntie “Mami”? Is that disrespectful? Can she say that because she’s black? Is anyone getting ripped off? Is black the same as Africa? The same as the Caribbean? Is the Auntie black? Is she yellow? Is she foreign? Is the Nigerian couple foreign? Are they Americans? Are the Chinese allowed to sell Afro-Caribbean flags? Are they allowed to sell “black” back to black folks? Are the Nigerians allowed to sell the Caribbeans?

There are biases and contradictions in all of these questions, which take root in my observation of describing to you what I saw in these minutes.

The weekend before, the news was flooded with the passing of Senator John McCain. A maverick, they called him. John McCain was a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War, which makes him one of our American war heroes. In 1967, he was shot down by the Viet Cong and they tortured him such that he was left with lifelong disabilities. This is the same Republican man who encouraged the Democratic President Clinton (and draft dodger) to open up diplomatic lines with Hanoi in 1993, and thus helped to heal the national wounds of a very long and painful war. This is also the same man who supported Republican President Bush to wage another long and painful war against Iraq. This is the same man who, in the middle of the night, showed up to Senate with a scar curling over his left brow from brain surgery and voted to save the Affordable Health Care Act. On Face the Nation that Sunday, Dan Balz, a journalist for the Washington Post, noted that unlike President Trump, John McCain always put “country first, not America first.”

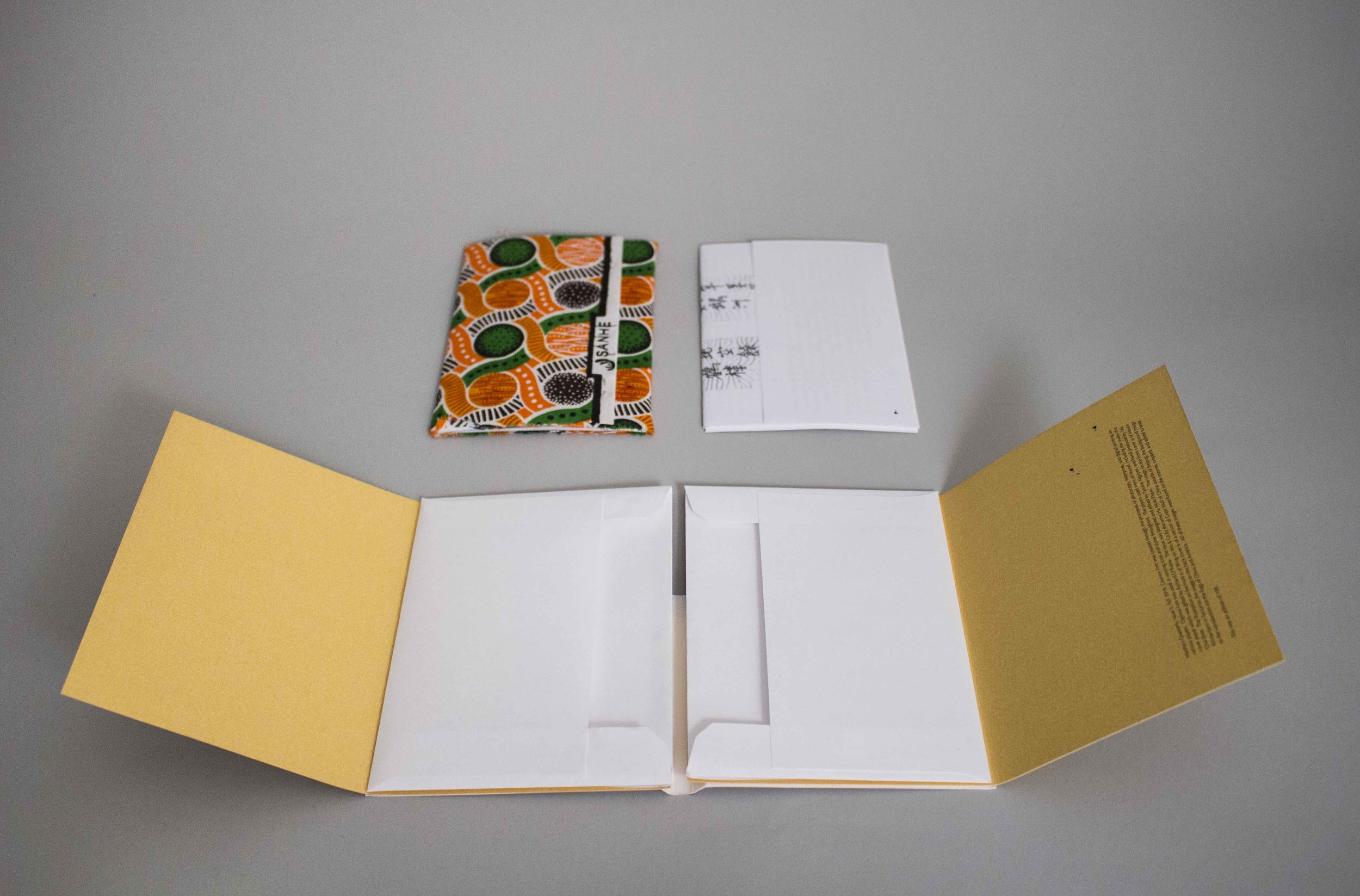

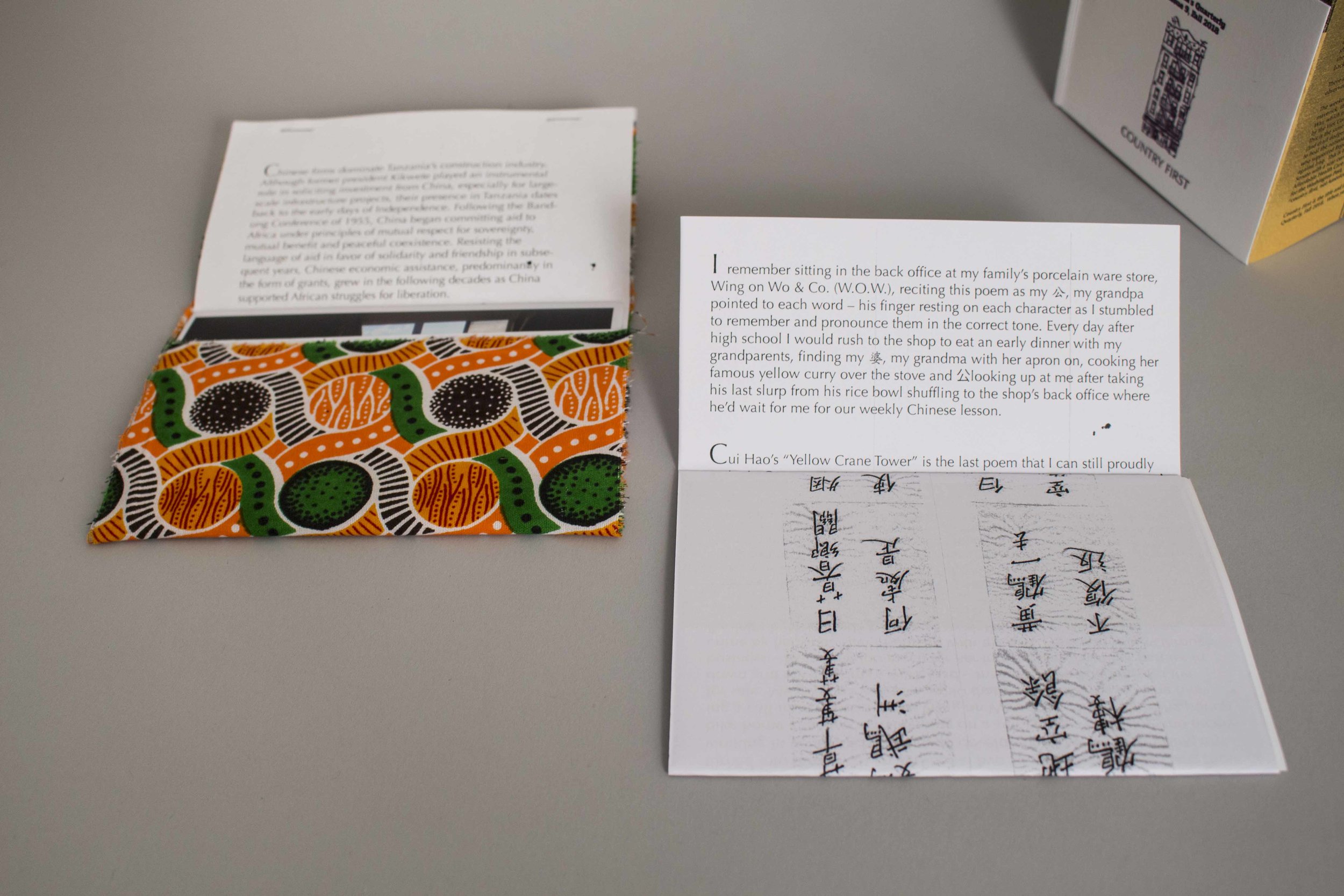

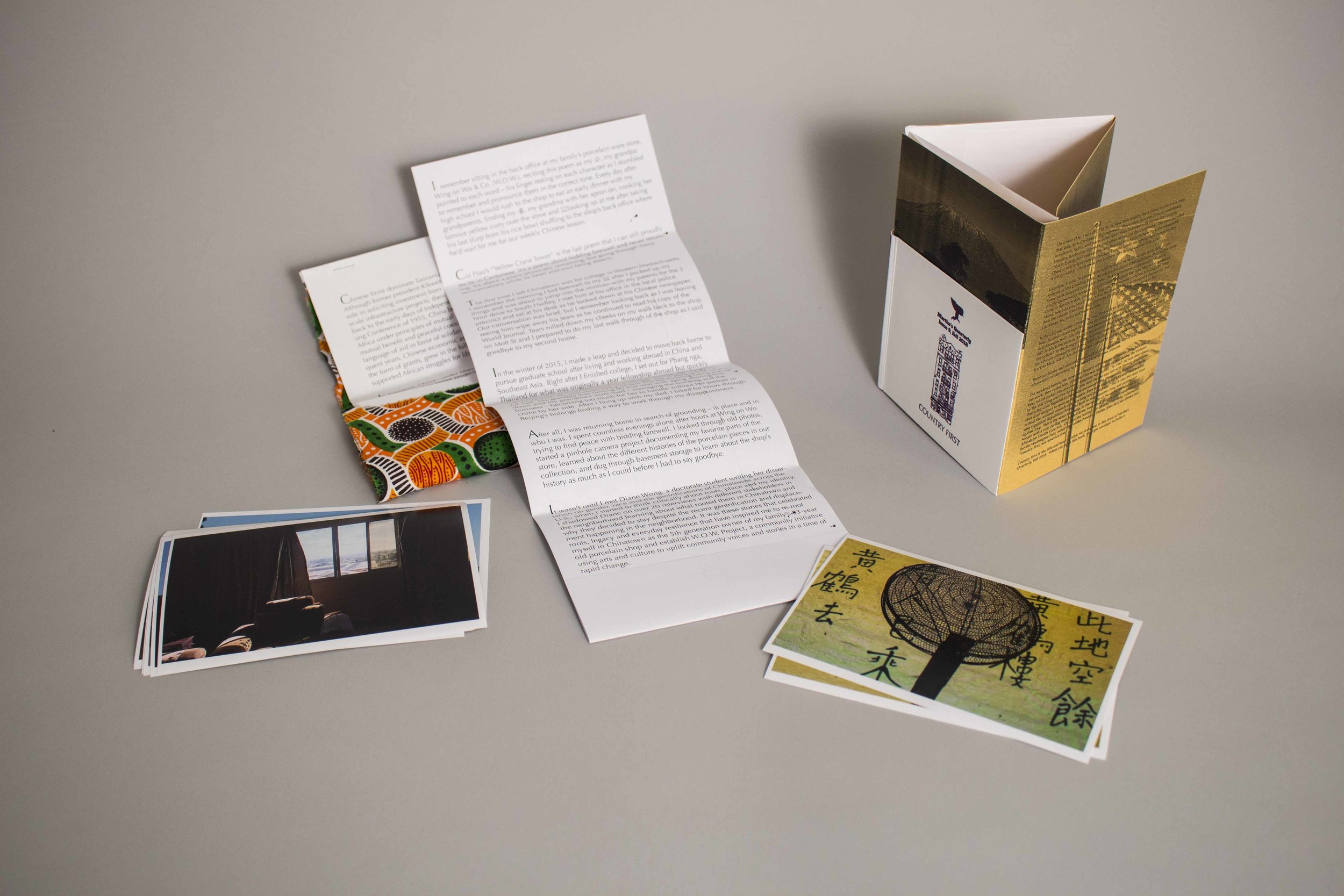

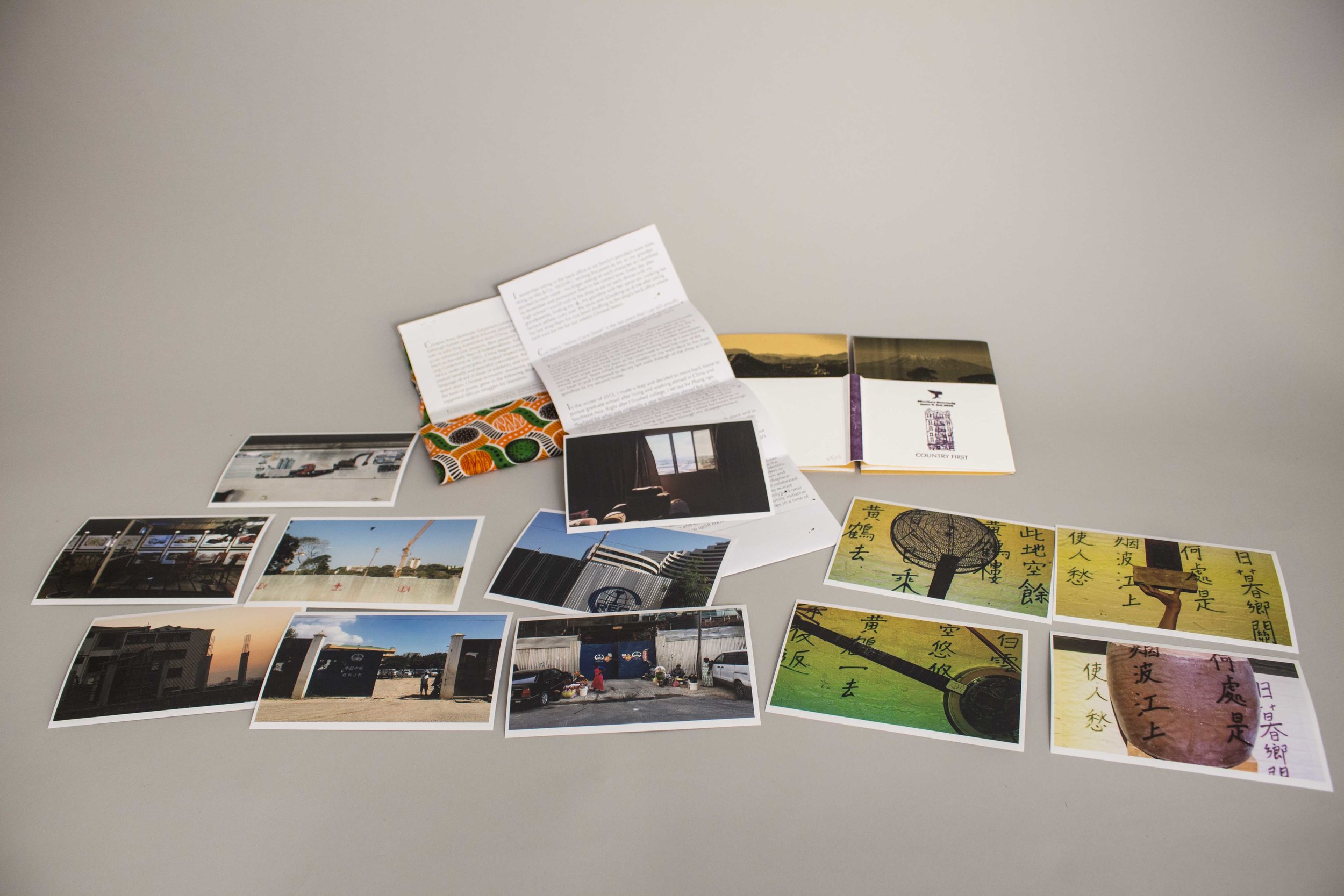

Country First is the title and heart of what we juxtapose in this issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Fall 2018. When you open this book, the right envelope includes a portfolio of photographs with writing by Mei Lum, the fifth generation owner of her family’s 93-year-old porcelain shop in New York’s Chinatown called Wing on Wo & Co. The photographs are wrapped with her grandfather’s calligraphy of the only poem she can still recite in Cantonese. On the other side of the paper, Lum recounts the the time she received the dizzying news from her father that the family planned to close Wing on Wo & Co. She was living in Beijing at the time, and as she cycled around this instrumental city in China, she thought of another China. Very soon thereafter she returned to her Chinatown in New York to regenerate the family business, to defend her “country” in the midst of an economic war against those outside of Lum’s Chinatown.

Far away from New York City, another kind of China has dominated Tanzania’s construction industry as illustrated by the writing and portfolio of photography by the Zimbabwean geographer Rakhee Kewada in the left envelope. As Kewada reports, China increased its support of Africa and demonstrated its support of sovereignty after the Bandung Conference of 1955. Over the years, this “support” which began as aid transformed into grants of significant projects, including the Tanzania-China Textile Mills. This drew many Chinese construction workers to Tanzania, and also birthed a booming real estate industry with which Tanzanians cannot compete. Whose country is first here?

Country First was John McCain’s campaign slogan in 2008 when he ran against soon-to-be America’s first black president Barack Obama. The slogan resonated with many: it encouraged people to be patriots, to work with the other side of the aisle, to see those different from you as your countrymen. Many of us know this to be easier in theory than in practice. Could you really call the man who calls you a slur because you are darker than he or because you are a woman your countryman? And if you can, will you also welcome him?

Whether you see yourself in your neighbor, the appetite of every nation seems to be to spread its own idea of country as in the case with America First. They might have called Mr. McCain a maverick, but if Culture was a person, then it would be the ultimate maverick. Culture is country, nation, and man— and conveniently can be certain or none of these things for people with intersectional identities. Culture sells itself at “Rasta Enterprise”, but it is not Jamaica, or Grenada, or Barbados. “Rasta Enterprise” is an American company. The Chinese woman selling the Afro-Caribbean flag is not an American. Ms. Lum is American in China, but Chinese in America. John McCain’s country is not the same as the Nigerian couple’s, but they both use the dollar. The Chinese in Tanzania are not African, but they do not belong with the Chinatown New Yorkers. Where can Tanzanians invest in real estate? In Tanzania? In Africa? In China? And would Chinatown, New York continue to fight if she truly knew the face of her gentrifier?

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 8

Summer 2018

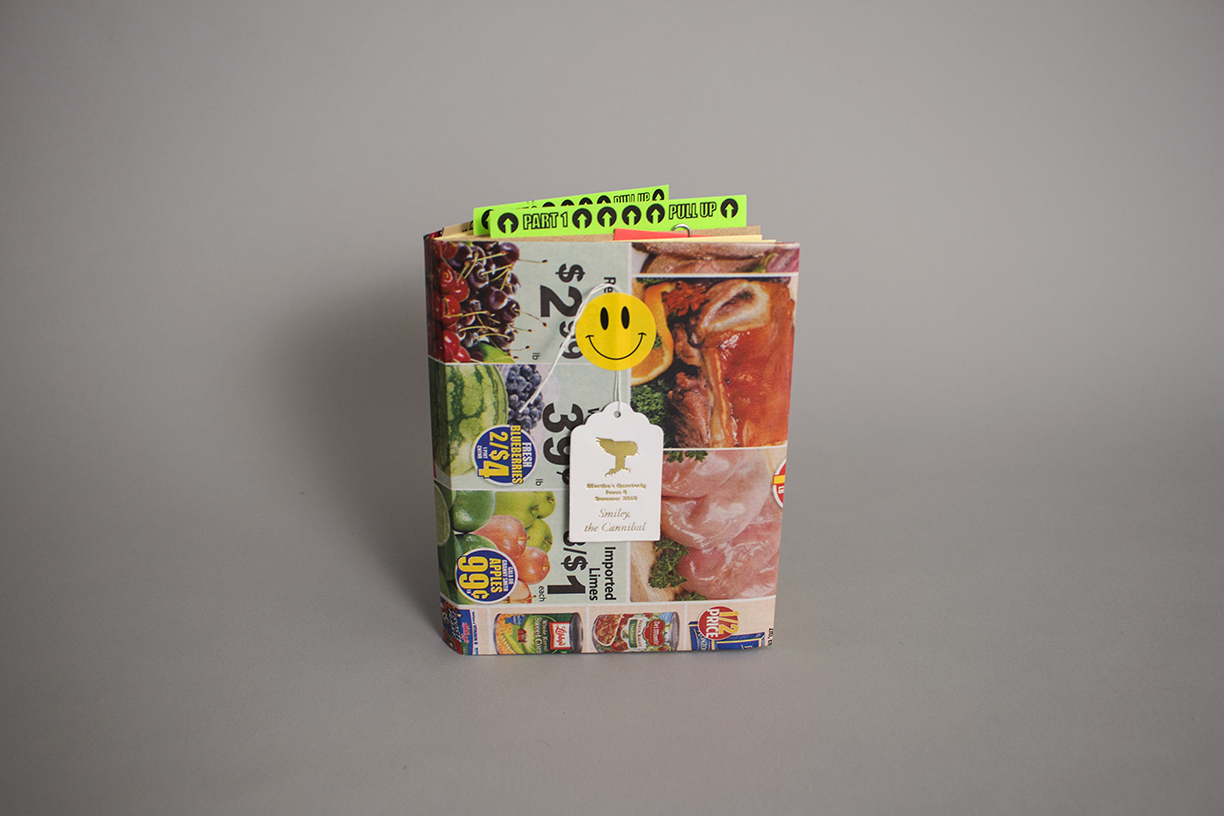

Smiley, the Cannibal

5.75” x 4.5”

About the contributors:

Jacob Hughes is a court jester at the Berkeley Carroll School with a doctorate in British Romanticism. His interests include literary form and style, hermeneutics, Joe Strummer, and intestinal aesthetics.

Taiwo Togun is the founder of SeqHub Analytics, a data science consulting company that provide predictive analytics and data science solutions and strategies to businesses. He earned his Ph.D in Computational Biology & Bioinformatics from Yale University, where his research focused on methods to identify genomic targets in cancer.

You are what you eat.

When you eat something, food enters your mouth. You chew, you swallow; it travels down your esophagus and into your stomach where it breaks down into smaller parts: amino acids, fatty acids, glycerol, and simple sugars. What you have eaten continues its travels into your small intestine, then your liver, gallbladder, and eventually your large intestine where what your body does not need transforms into feces and exits your body through your anus. This whole system is your gastronomical tract, a system of hollows connected by a tube where nutrients are absorbed and become one with your body.

Some raucousness was stirred when Secretary of Homeland Security Kirsten Nielsen was spotted eating at MXDC Cocina Mexicana by celebrity chef Todd English. (1) The irony of this event was clear, as at the same time the Trump Administration approved of a heinous family separation policy at the US southern border. The entrees at MXDC Cocina Mexicana range from $17 - $38. On its website the restaurant’s “About” page shares that Mr. English was “inspired to create MXDC Cocina Mexicana by his travels to Mexico. English's first restaurant job was at a small Mexican eatery during high school, where he grew to love the rich cuisine.” (2) And, like at many high-end restaurants across America, the majority of the staff at this establishment are Latinx. So, as Ms. Nielsen’s Mexican entree becomes one with her body, the nutrients she is absorbing come from the hands of the Latinx workers upon whose lives she is wreaking havoc.

It is no secret that Latinx immigrants are the backbone of the American restaurant industry. Their labor is cheap and they do many of the jobs that American citizens do not want to do. And here’s another open secret: Capitalism has always known how to connect the cent to a human body, documented or not. Capitalism knows this in its soul, and it knows that to become stronger, bigger, and great again, it is best to continually apply the lowest amount of cents to the largest amount of human effort. In this way, it can eat the cents produced by that human effort.

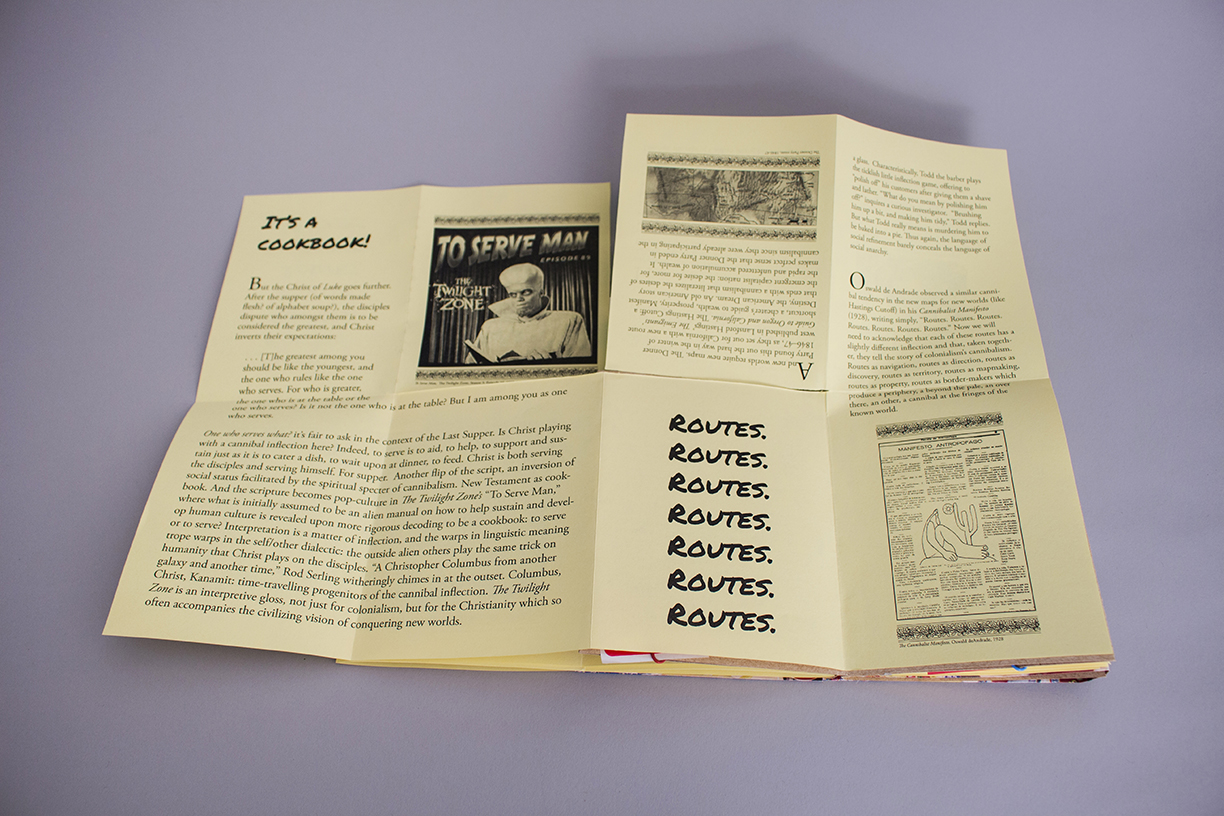

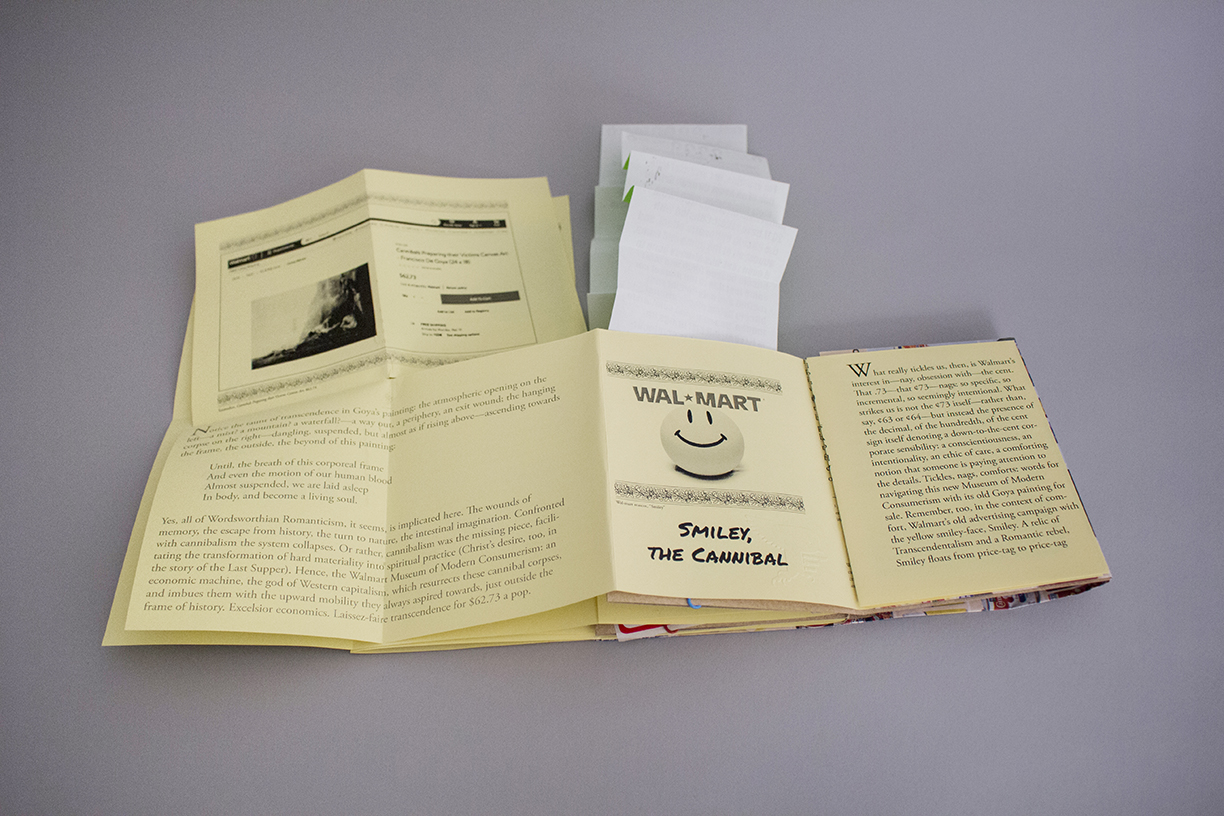

In Christianity, Capitalism’s brother from another mother, the Eucharist is perhaps the most sacred of sacraments: one’s body can be one with that of Christ by eating a wafer and drinking wine that represent Christ’s flesh and blood. In some ways, this sacrament is what Capitalism performs countless times each and everyday: consuming the flesh and blood of its own producers through the products created by those same humans. This is the crux of our exploration in this issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 8, Smiley, the Cannibal, which features contributions by Dr. Jacob Hughes, an English Literature Scholar, and Dr. Taiwo Togun, a data scientist.

Dr. Hughes takes us down a kind of digestive tract of his own, where he illustrates the many ways in which cannibalism is manifested throughout our culture, from the Eucharist to the Twilight Zone, to the savings we enjoy at Walmart, its Smiley face mascot knocking all the prices down by the cent. One point he makes is that capitalism relies on this cent-to-object/human relationship, and that that relationship is a cycle of consumption and releasing, of eating and excreting.

On July 11th, 2018, just five days before I write this, President Trump intensified his trade war with China by announcing 200 billion dollars worth of tariffs on Chinese goods to be imposed in September. A list of more than 6,000 products was released, including a tariff on all Chinese canned tuna and cotton thread. (3) As this trade war becomes more palpable to us-- maybe by a sudden craving for rare canned tuna, or a more urgent worry when our clothes become tattered-- the relationship between the cent and human products will become more physically and viscerally tangible. New people, many people, will resent China, the United States, and whatever nation is making their cent to human product relationship more fragile.

But we are at the advent of a new force: cryptocurrency and the blockchain, where what something is worth does not necessarily direct back to one nation’s economy, and therefore the cent no longer attaches itself to the human product and the human as decisively. I asked Dr. Togun to explain how cryptocurrency changes the relationship between money and the object. How does Capitalism change when the economy is no longer tied to a concrete object? In an almost propagandist three concise paragraphs, Dr. Togun explains the profound concept of “secure transfer of value via networks without a central oversight.” There’s no more cannibalism here-- it was our singular gastronomical tract which allowed for the capital consumption of our bodies through our own goods.

A year ago from this writing, China became the first country to test a national cryptocurrency. (4) Today, more than 70% of the world’s crypto-mining occurs in China for two big reasons: cheap electricity and an excess of coal. (5) Despite its efforts to release itself from a self-consuming structure, cryptocurrency can still only be birthed from cannibalism. Or maybe there is metamorphosis occurring, that the Cannibal has transformed into another beast we just cannot understand quite yet.

— Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1)The Absurdity of Trump Officials Eating at Mexican Restaurants During an Immigration Crisis, Helen Rosner, The New Yorker, June 22, 2018

(2) https://www.mxdcrestaurant.com/our-team/

(3) US fires next shot in China trade war, BBC News, July 11, 2018

(4) China Becomes First Country in the World to Test a National Cryptocurrency, by Tom Ward and Abby Norman , Futurism, June 23, 2017

(5) Bitcoin Mining in China, Jordan Tuwiner, June 30, 2018

Martha's Quarterly

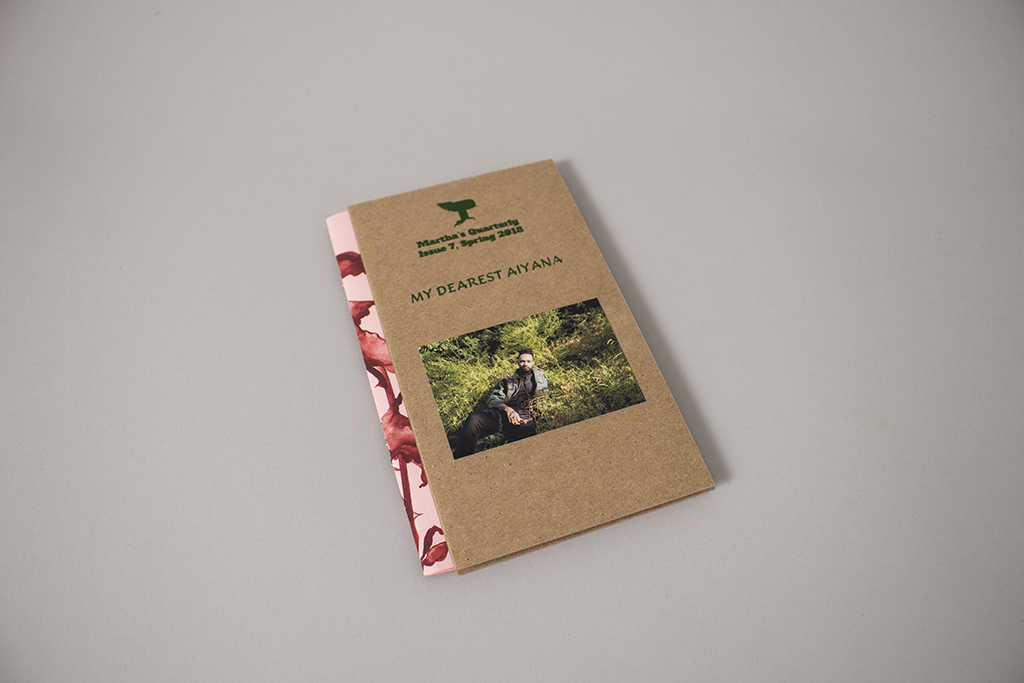

Issue 7

Spring 2018

My Dearest Aiyana

6.5” x 4.25”

About the contributors:

Daniil Davydoff is manager of global security intelligence at AT-RISK International and director of social media for the World Affairs Council of Palm Beach. His writings on security and international affairs have been published by ASIS International, Security Magazine, Risk Management Magazine, The National Interest, the Tehran Times, Foreign Policy, and RealClearWorld, among other outlets.

Naima Green is a Brooklyn-based artist and educator interested in teasing the boundaries of intimacy, urban ecology, and the construction of home.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen uses his artistic practice to find god. He initiated an artist collective called The Propeller Group to uncover the devil.

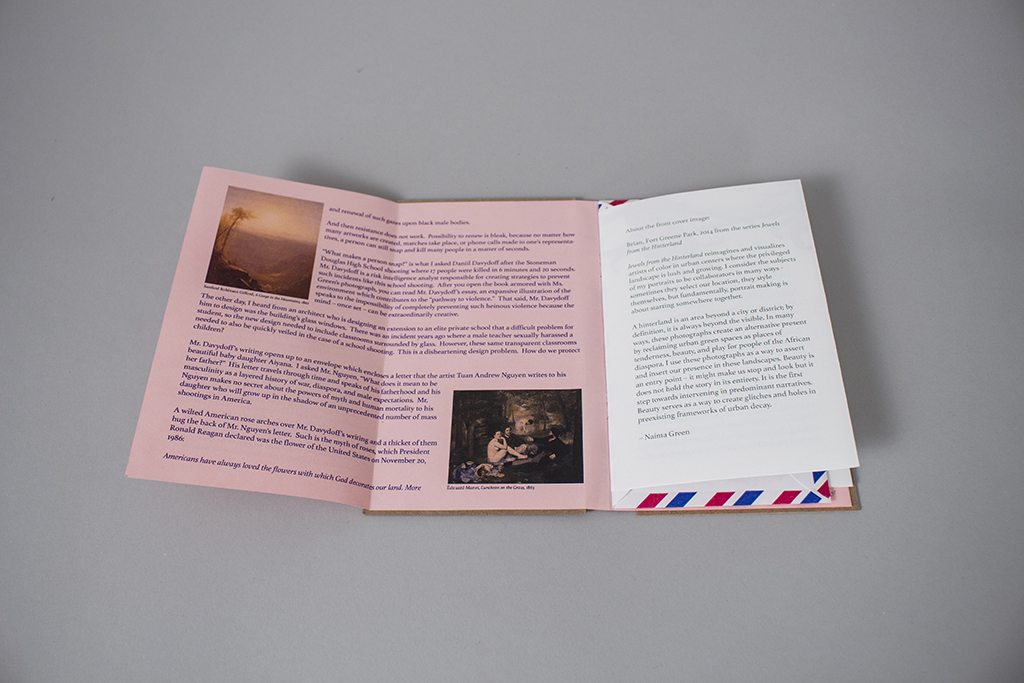

I’d like you to think about this book’s cover as the arms of someone and they are hugging the contents inside, which are some of the most precious things in the world.

The cover of this book starts with an idea of landscape, which was a protector to me when I was a child. I remember seeing El Capitan in Yosemite and thinking it was there to protect the forest. I remember seeing landscape paintings from the Western Expansion and thinking that these places were for me to be safe. But in my adulthood, I think of landscape as more of a force which could either protect or kill me. While I can blissfully inhale the sky of Sanford Robinson Gifford’s painting A Gorge in the Mountains, I see an absence of humans and a land to be taken. While I could imagine what the foods taste like in Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass, I doubt people of color would have been invited to such an affair, or if a person of color could occupy the landscape in such a way and in such a time.

Sanford Robinson Gifford, A Gorge in the Mountains, 1862

This is partly why I have been drawn to Naima Green’s ongoing project Jewels from the Hinterland where she photographs black people in landscapes as a way to make them the center focus. The cover of this Martha’s Quarterly features Brian, and when I look at this image, I wonder about Brian as an individual but also as a representation of the Black male. In recent years, the impulse to depict Black men in more nuanced and complicated ways is one form of response to the reckless of treatment of black bodies ranging from racist 911 calls to needless gun violence. Ms. Green’s portrait performs a resistance and renewal of such gazes upon black male bodies.

And then resistance does not work. Possibility to renew is bleak, because no matter how many artworks are created, marches take place, or phone calls made to one’s representatives, a person can still snap and kill many people in a matter of seconds.

“What makes a person snap?” is what I asked Daniil Davydoff after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting where 17 people were killed in 6 minutes and 20 seconds. Mr. Davydoff is a risk intelligence analyst responsible for creating strategies to prevent such incidents like this school shooting. After you open the book armored with Ms. Green’s photograph, you can read Mr. Davydoff’s essay, an expansive illustration of the environment which contributes to the “pathway to violence.” That said, Mr. Davydoff speaks to the impossibility of completely preventing such heinous violence because the mind – once set – can be extraordinarily creative.

Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass, 1863

The other day, I heard from an architect who is designing an extension to an elite private school that a difficult problem for him to design was the building’s glass windows. There was an incident years ago where a male teacher sexually harassed a student, so the new design needed to include classrooms surrounded by glass. However, these same transparent classrooms needed to also be quickly veiled in the case of a school shooting. This is a disheartening design problem. How do we protect children?

Mr. Davydoff’s writing opens up to an envelope which encloses a letter that the artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen writes to his beautiful baby daughter Aiyana. I asked Mr. Nguyen, “What does it mean to be her father?” His letter travels through time and speaks of his fatherhood and his masculinity as a layered history of war, diaspora, and male expectations. Mr. Nguyen makes no secret about the powers of myth and human mortality to his daughter who will grow up in the shadow of an unprecedented number of mass shootings in America.

A wilted American rose arches over Mr. Davydoff’s writing and a thicket of them hug the back of Mr. Nguyen’s letter. Such is the myth of roses, which President Ronald Reagan declared was the flower of the United States on November 20, 1986:

Americans have always loved the flowers with which God decorates our land. More often than any other flower, we hold the rose dear as the symbol of life and love and devotion, of beauty and eternity. For the love of man and woman, for the love of mankind and God, for the love of country, Americans who would speak the language of the heart do so with a rose.

We see proofs of this everywhere. The study of fossils reveals that the rose has existed in America for age upon age. We have always cultivated roses in our gardens. Our first President, George Washington, bred roses, and a variety he named after his mother is still grown today. The White House itself boasts a beautiful Rose Garden. We grow roses in all our fifty States. We find roses throughout our art, music, and literature. We decorate our celebrations and parades with roses. Most of all, we present roses to those we love, and we lavish them on our altars, our civil shrines, and the final resting places of our honored dead.

The American people have long held a special place in their hearts for roses. Let us continue to cherish them, to honor the love and devotion they represent, and to bestow them on all we love just as God has bestowed them on us. (1)

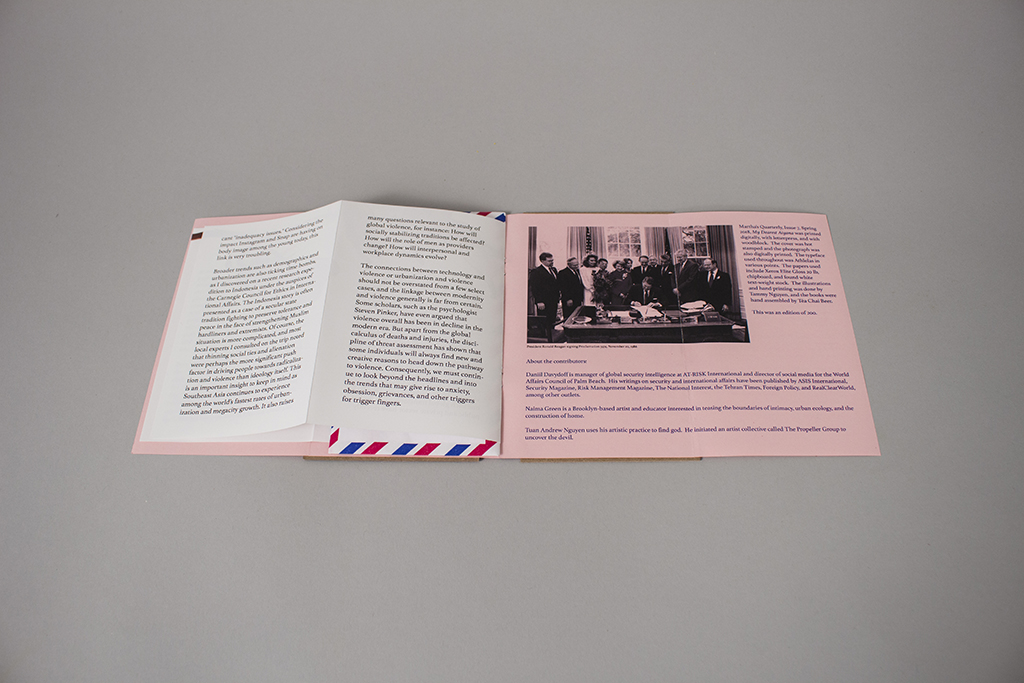

President Ronald Reagan singing Proclamation 5574, November 20, 1986

Roses have been laid on the dead bodies of Black male victims, as they have been laid on all of the slain from the Stoneman Douglas shooting. One day a rose will be given to Aiyana. All these roses from the American landscape. Such is the myth of landscape, men, and manifest destiny.

— Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

1 The National Flower, http://nationalrosegarden.com/the-national-flower/

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 6

Winter 2018

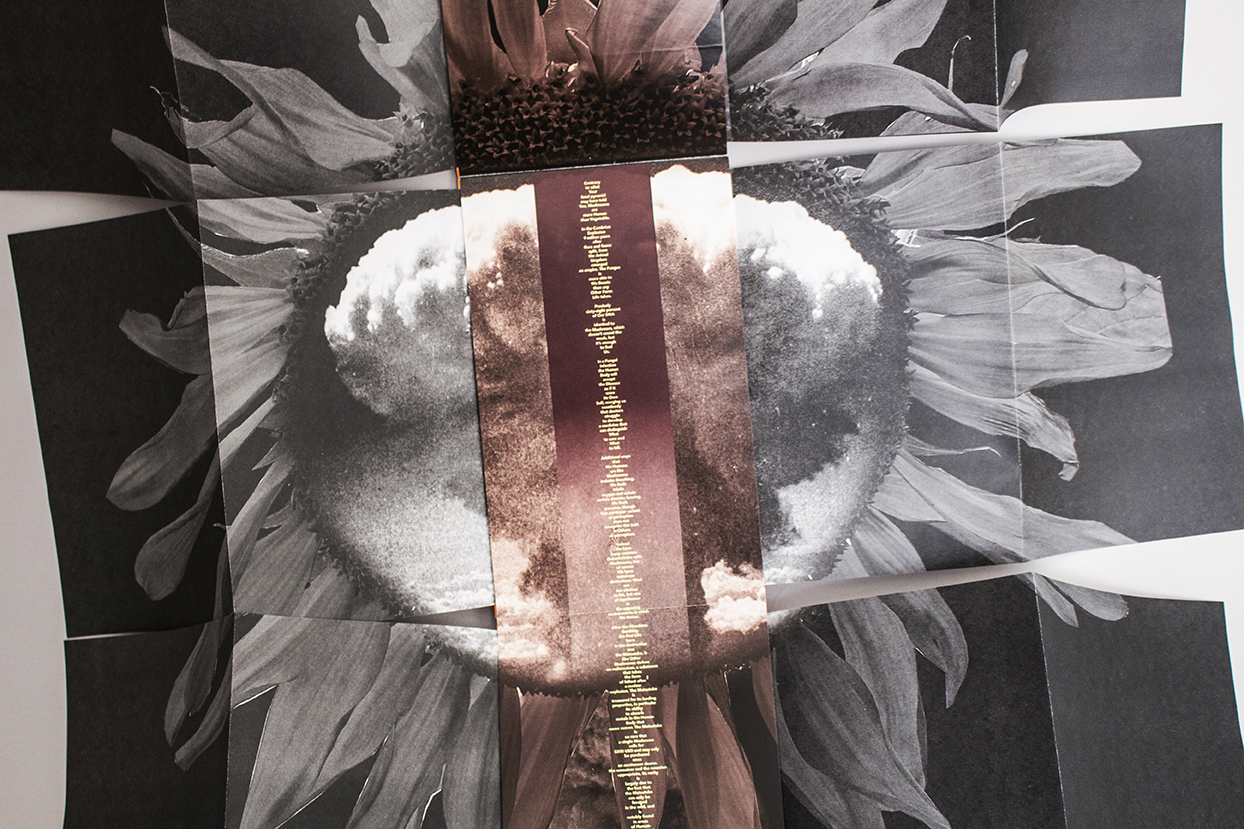

Fields of Fungus and Sunflowers

8” x 5”

About the contributors:

Everything Adriel Luis does is driven by the belief that social justice can be achieved through surprising, imaginative and loving methods. His writing, music, designs and curatorial work to this end can be found at drzzl.com.

Lovely Umayam is the founder of Bombshelltoe, a project examining the intersection of nuclear policy, arts, and community organizing to achieve a nuclear weapons-free world. She is also a Program Manager at the Stimson Center in Washington DC, where she develops programs to secure civilian nuclear material and technologies from being disseminated and misused for nuclear weapons development.

What happens when the thing you can’t possibly imagine happens?

When the Winter Olympics opened this year, South Korea and North Korea walked together, teasing a united Korea to the entire world. Vice President Pence sat in front of Kim Yo Jong, the sister of Kim Jong Un— they didn’t exchange any words. Days later, Korean-American teenager Chloe Kim took gold for America in the Women’s halfpipe, stunning the world with back to back 1080s.(1) As she came down the pipe, her father, who immigrated to the United States from South Korea in 1982, held a sign reading “Go Chloe!” as he shouted, “American Dream!”(2)

What happens when the worst thing is about to happen?

A few months ago, all of the smart phones in Hawaii alarmed in unison and alerted the people that there was a ballistic missile headed towards the islands. A long 38 minutes after, people were informed that the alert was a mistake. William J. Perry, who was Secretary of Defense under Clinton, recalled a time when a watch officer reported that 200 intercontinental ballistic missiles were headed to the United States. In his memoir My Journey at the Nuclear Brink, he wrote, “For one heart-stopping second I thought my worst nuclear nightmare had come true.” (3) But somewhere on the Hawaiian Islands that day, Joshua Keoki Versola opened himself a bottle of Hibiki 21 and waited for his fiancée to return home. (4)

And then the worst thing happens...

On Valentine’s Day of 2018, an American teenager gunned down 17 members of his former high school in Parkland, Florida.

Recent events have pushed people to see the brink. Sometimes, we see what is beyond that brink which has ranged from glory to devastation. Nuclear threat might be one of the least comprehensible threats on the global stage. What does it mean? What happens? Could it happen? How is it possible? And then what? Do we stop? These kinds of questions swirl in my constantly unstill and perplexed mind.

And so, I asked Lovely Umayam, a nuclear policy analyst at the Stimson Center in Washington DC, How will something begin to grow after nuclear war? This Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 6, Winter 2018, Fields of Fungus and Sunflowers, features Ms. Umayam’s answer. I also asked Adriel Luis, musician/poet/visual artist/curator/coder to respond to my question and Ms. Umayam’s response with something lyrical. Upon receiving Mr. Luis’ poem, I read it outloud. As my eyes followed the poem’s dramatic verticality, I saw the words fungus, beast, DNA, cancer, and human stack like bricks of a tower representing our fragile civilization.

— Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

(1) How Chloe Kim Won Gold With a Nearly Perfect Score in Halfpipe, By Alexandra Garcia, Haeyoun Park, Bedel Saget, Joe Ward, Margaret Cheatham Williams, and Jeremy White, NY Times, Feb. 13, 2018.

(2) Chloe Kim: Meet the Olympic snowboarder who won gold, by Daniel Arkin, The Associated Press, Feb.14, 2018

(3) Hawaii Panics After Alert About Incoming Missile Is Sent in Error, by Adam Nagourney, David E. Sanger, and Johanna Barr, NY Times, Jan. 13, 2018

(4) Hawaii ballistic missile false alarm results in panic, Julia Carrie Wong and Liz Barney, The Guardian, Jan. 14, 2018.