MQ 2021

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 21

Fall 2021

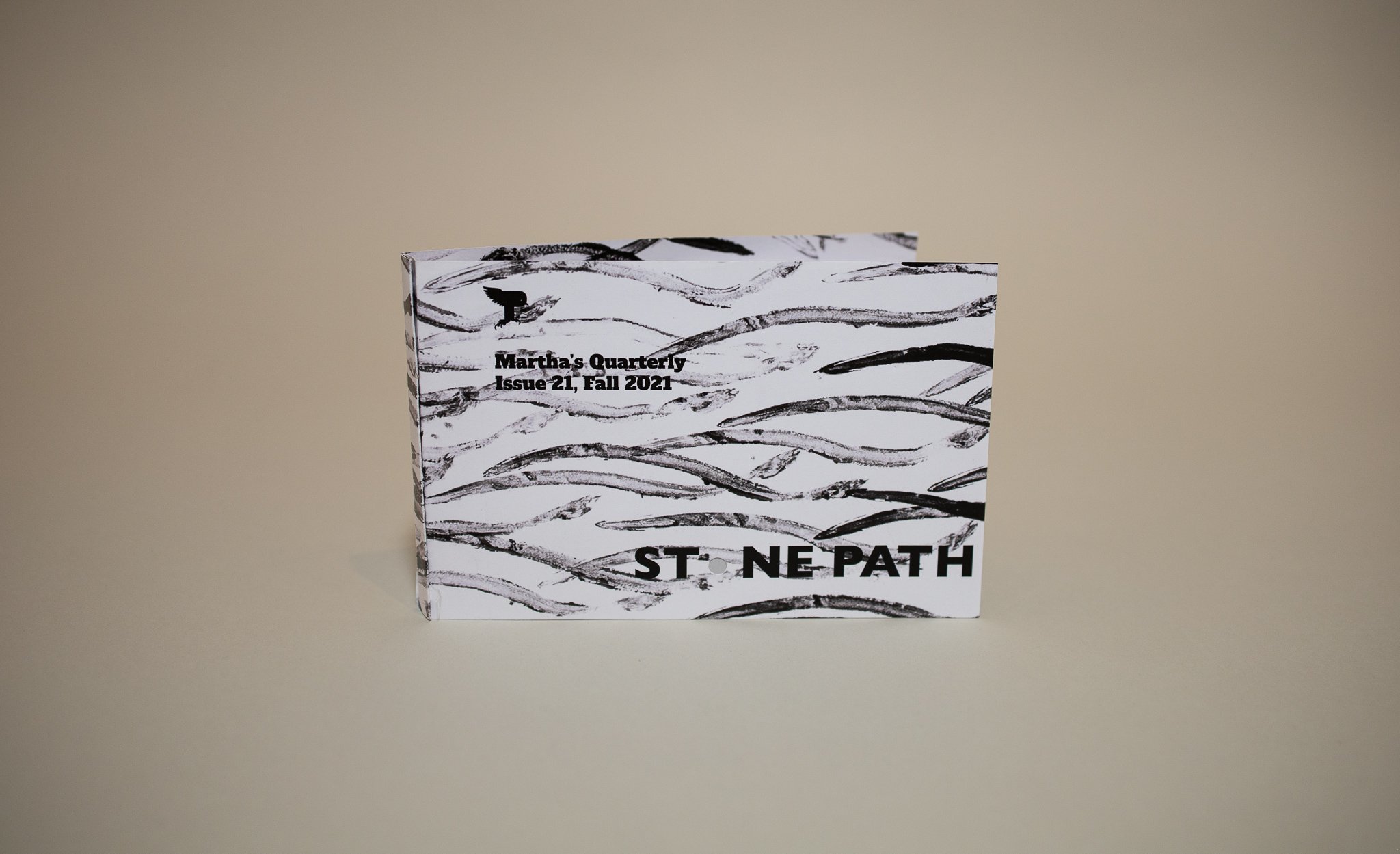

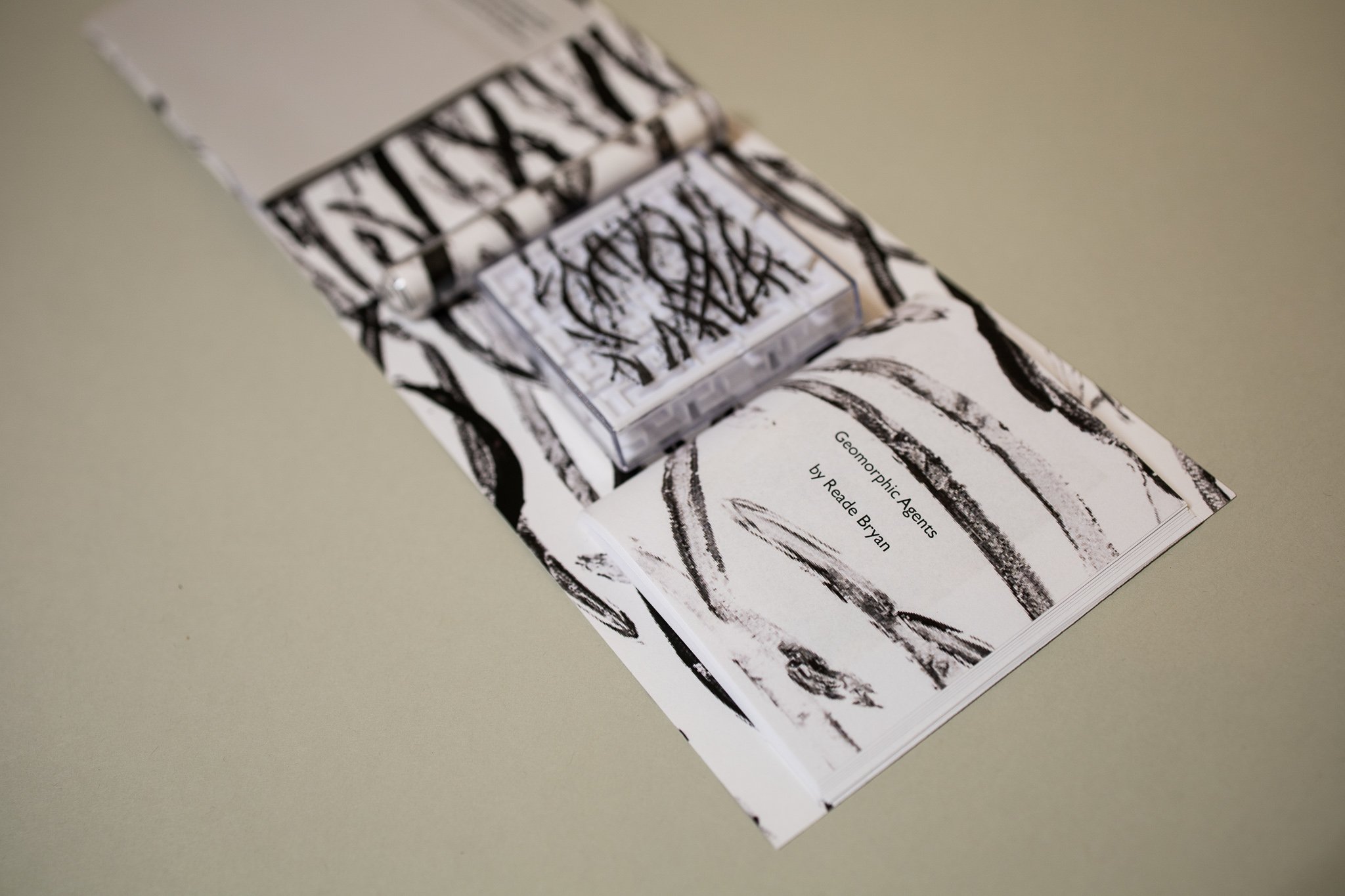

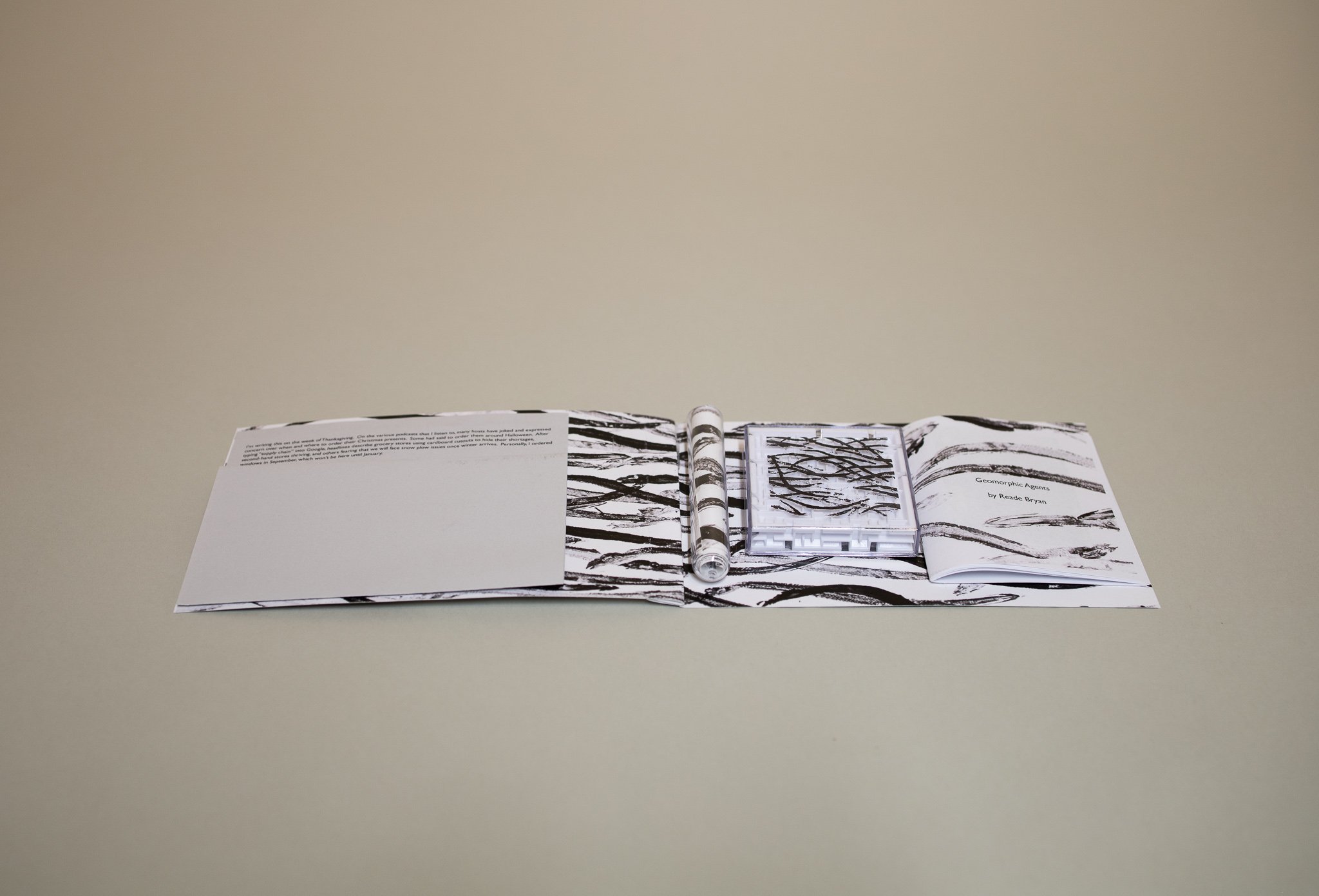

Stone Path

5” x 7”

About the contributors:

Reade Bryan is an interdisciplinary artist living in Philadelphia. He’s been watching a ton of Korean films from the 70’s and becoming a Cold War history buff.James Prosek is an artist and writer living in Easton, Connecticut. His show Art, Artifact, Artifice at the Yale University Art Gallery ran through 2020 and early 2021.

I’m writing this on the week of Thanksgiving. On the various podcasts that I listen to, many hosts have joked and expressed concern over when and where to order their Christmas presents. Some had said to order them around Halloween. After typing “supply chain” into Google, headlines describe grocery stores using cardboard cutouts to hide their shortages, second-hand stores thriving, and others fearing that we will face snow plow issues once winter arrives. Personally, I ordered windows in September, which won’t be here until January.

Outside the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles in California, hundreds of freight ships are waiting to unload thousands of containers of goods to be distributed across the nation. This is the busiest port complex in America and ninth largest in the world. But, there is an immense shortage of trucks, drivers, and warehouse workers who will unload the cargo and transport them to their destinations. This bulging problem has been largely (but not totally) driven by the pandemic, when consumer sales increased but there wasn’t enough of a workforce to complete the distribution on a global scale.

My interest in the supply chain is multifaceted, but in this issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 21, Fall 2021, Stone Path, I want to consider how the supply chain is actually an extension of Man’s manipulation of nature. The supply chain, and its former swiftness, is a reflection of how nations, capitalism, and peoples have been able to command nature by creating clear passages for culture to pass.

For another project, I was researching the Phong Nha Karst and became awestruck by the simplicity and effectiveness of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. During the American War in Vietnam, the Northern Vietnamese Communist Army needed to find a way to transport goods, such as weapons and food, to their Southern loyals. Vietnam’s coastline was occupied by the United States, so they created a network of people through the Phong Nha caves in eastern Vietnam. This was a supply chain– a network of people, transporting goods across short distances, who all linked together until the goods got to their final destination. Many historians credit the Ho Chi Minh Trail for being a major reason why the Vietnamese Communists were able to win the war. In other words, it was because of a supply chain that the United States was defeated.

But the Phong Nha Karst provided nothing close to a clear path for transportation. During my research trip, I went spelunking in the caves. The trails throughout the jungle were arduous and sometimes required one to be creative with their footsteps to avoid tripping and being cut from sharp plants. The passage through the caves required climbing and swimming. At the end of the day, every muscle in my body kept a memory of the jungles in the form of an ache.

This bodily experience expanded the way that I thought about Man’s quest to take over territory. Nature is tough, and to command over her takes the extraordinary strength and endurance of thousands of people combined. However, when you see the result of taming a territory, the image is of a grand interstate highway, a water canal, a train track, etc; and, the many people who helped to shape Nature are gone from the image.

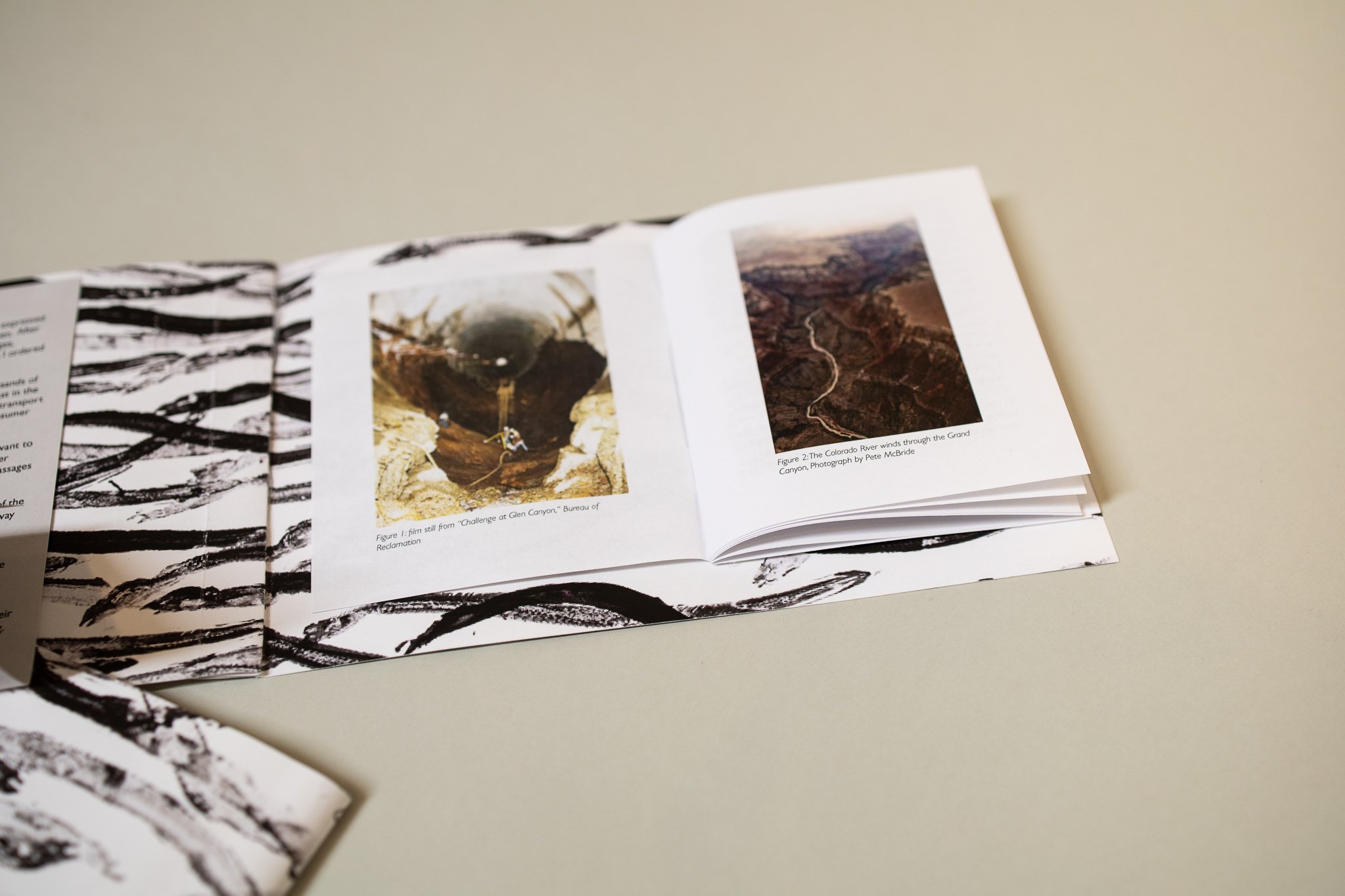

These are various reasons I wanted to combine the work of Reade Bryan and James Prosek in this issue of Martha’s Quarterly. Reade researches land reclamation projects, and the pamphlet features a variety of sites he has collected in his research archives. Looking at these images, I was struck by how visionary and invasive these projects were. For example, Reade presents how the Aral Sea, a formerly landlocked body of water, became unlocked when irrigation systems were designed around it to extract its resources for agriculture. As a result, the shape of the body of water has completely morphed and shrunk over time, as shown in the satellite images.

Repeated all over this artist book are eel prints created by James Prosek, who has studied them for decades. In an excerpt from his book Eels, which is rolled up in the water vial, Prosek describes the many mysterious characteristics of eels that have made them an evolutionary marvel for many scientists and enthusiasts. In trying to pinpoint what they are and where they came from, Prosek points out that they are found in landlocked bodies of water such as lakes and ponds with no visible connection to the sea. Prosek writes, “On wet nights, eels are known to cross over land from a pond to a river, or over an obstruction, by the thousands, using each other’s moist bodies as a bridge.” He continues, “The yearly journeys millions of adult eels make from rivers to oceans must be among the greatest unseen migrations of any creature on the planet.”

I wanted to contrast the stealthy, smooth, seamless, and undisturbed movement of eels to the disruptive yet innovative movement of people around the planet. What does it mean to get what you want seemingly without affecting others?

Centered between Prosek’s and Bryan’s pieces is a toy maze with more eels swimming across its surface. You are welcome to roll the silver ball around to help it find passage to its “destination”. This ball could be a package, a person, a message, and more. As it hits each wall, think about how much easier it would be if you could just knock that wall down. Or, alternatively, wish that the ball was more like an eel, able to slither to its destination without disrupting Nature or other Men.

– Tammy Nguyen

Editor-in-Chief

This issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 21, Fall 2021, Stone Path was created using Xerox printing and print-on-demand technologies. The papers used included white 80 lb cover stock, 20 lb plain text weight, and 30 lb plain text weight. Gill Sans font was used in various sizes and styles throughout. Reade Bryan’s text was adapted from a presentation he gave at Smack Mellon in the Summer of 2021 and was edited by Chloe Greene. James’ Prosek’s text was excerpted from his book Eels, published by HarperCollins in 2010, and edited for our use by Holly Greene. This edition was produced by Téa Chai Beer, Clara Burger, Chloe Green, Holly Greene, Spencer Klink, and Mely Kornfield. It was designed and directed by Tammy Nguyen. This was an edition of 200.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 20

Summer 2021

Composition Gold

6” x 6”

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 20, Summer 2021, Composition Gold

About the contributors:

Tae-Yeoun Keum is a political theorist teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on ancient political theory, German social thought, and the symbolic dimensions of politics.Rodrigo Valenzuela (b.Santiago, Chile 1982) lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, where he is the Assistant Professor and Head of the Photography Department at UCLA. Valenzuela has been awarded the 2021 Guggenheim Fellowship in Photography and Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship; Joan Mitchell award for painters and sculptors; Art Matters Foundation grant; and Artist trust Innovators Award.

What does it mean to be noble?

The most straightforward understanding of this word is when it refers to those people who have noble blood, for whom such rank is usually hereditary. Those people are generally members of royal families, related to national monarchs through blood relations, and regarded as part of the highest and usually ruling class of their society. Though the noble class most often does not work in everyday professions, its members can have duties that range from charity work to diplomatic appearances and military leadership. They are usually expected to behave with a certain visible presentation of elegance and dignity; this is why stories like Prince Andrew partying with underage girls with Jeffrey Epstein are enticing to the public and a catastrophe for Buckingham Palace’s public relations, as well as why royal weddings can draw enormous virtual crowds.

This idea of etiquette is related to the second, more fluid, and more complicated understanding of the word noble, which means to show or possess high moral principles and ideals. In some religious communities and various ethno-states, what is deemed moral is indisputable. And, for the most part, there are some principles—such as murder and theft—that are distinctly labeled as wrong across cultures, even within a diverse society that shares different values. But, it is within the more commonplace roles that humans play in our societies where what is noble becomes flexible and can, at times, even become exploitative.

This issue of Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 20, Summer 2021, Composition Gold, brings together an essay by classicist Tae-Yeoun Keum and photographs by artist Rodrigo Valenzuela to explore questions of nobility and class, labor and imagination, and fate and agency. I was inspired when I listened to someone talk about the noble lie, a kind of myth often told by the elite or ruling class of a society that is meant to maintain social harmony. In monarchies and caste system societies, the noble lie is essential to keeping people spread across different classes, in their place and seldom questioning their situation. Today, many democratic societies also use a noble lie that many accept: “meritocracy,” i.e. the idea that one is rewarded and can move between classes as a result of one’s hard work and talent.

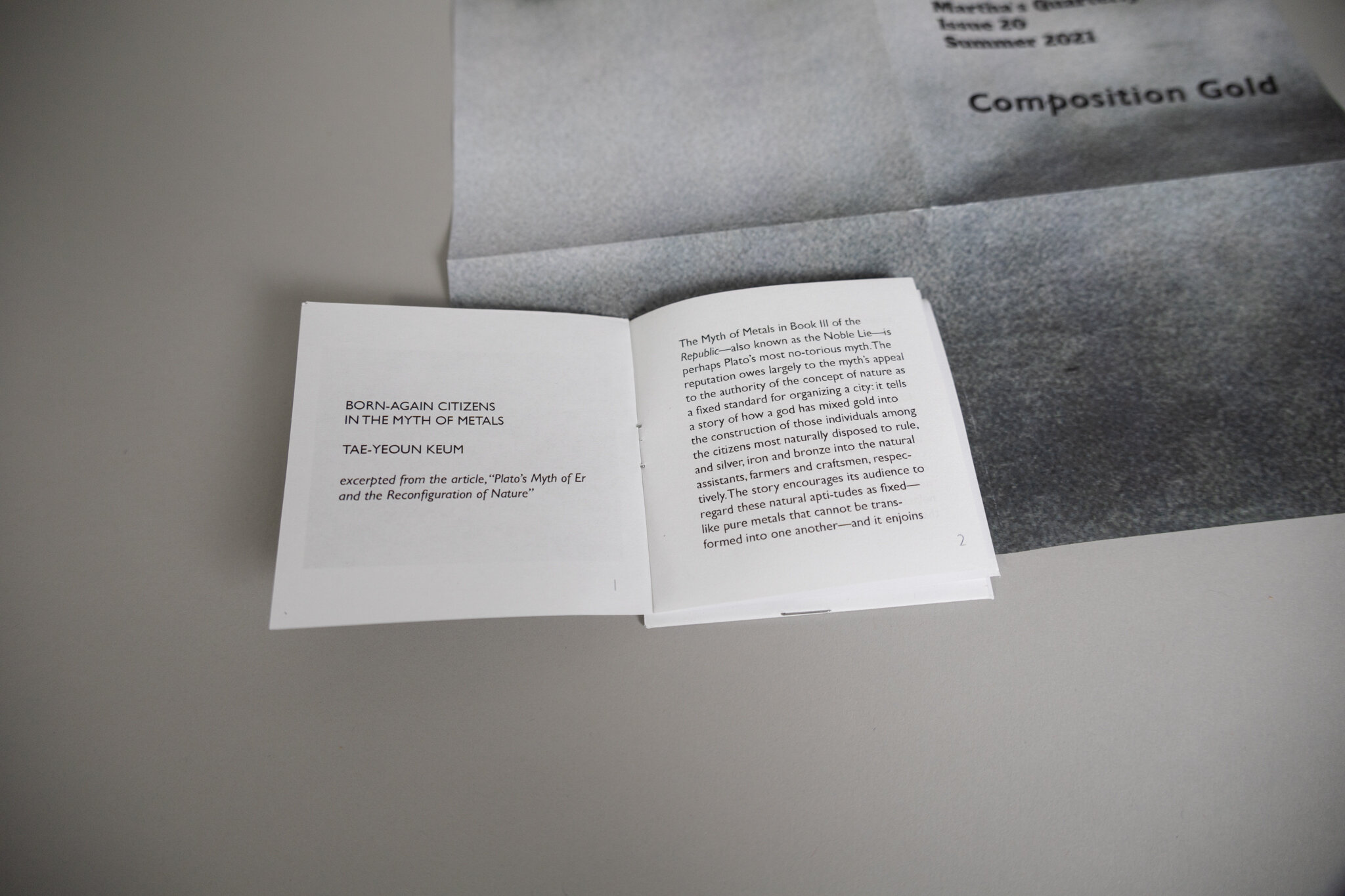

In Tae-Yeoun Keum’s essay, she retells the story of the noble lie, which originated in Plato’s Republic and is popularly known as the Myth of Er. The most common, simple, and somewhat crass summary of this story is that men come into the world with metals mixed into their composition, and the value of these metals determines their class. Those composed of gold become part of the ruling elite, and other people who are composed of silver, iron, or bronze fill in the other roles of a society, such as farmers and laborers. This reading of the Myth of Er became notorious and was embraced by Nazis, as suggested in their national slogan “Blood and Soil.”

Keum’s essay presents a provocative and more complex interpretation of this story: she emphasizes the opening passage of the myth, where the moment of birth is defined. Unlike the common assumption that birth occurs when a baby emerges from their mother, the opening lines to the Myth of Er suggest that birth is an event that occurs after a person has completed a primary education. This, therefore, completely shifts the notion that people are destined to certain classes by a natural selection; rather, it puts the Myth of Er more intimately in discourse with the idea of a meritocracy.

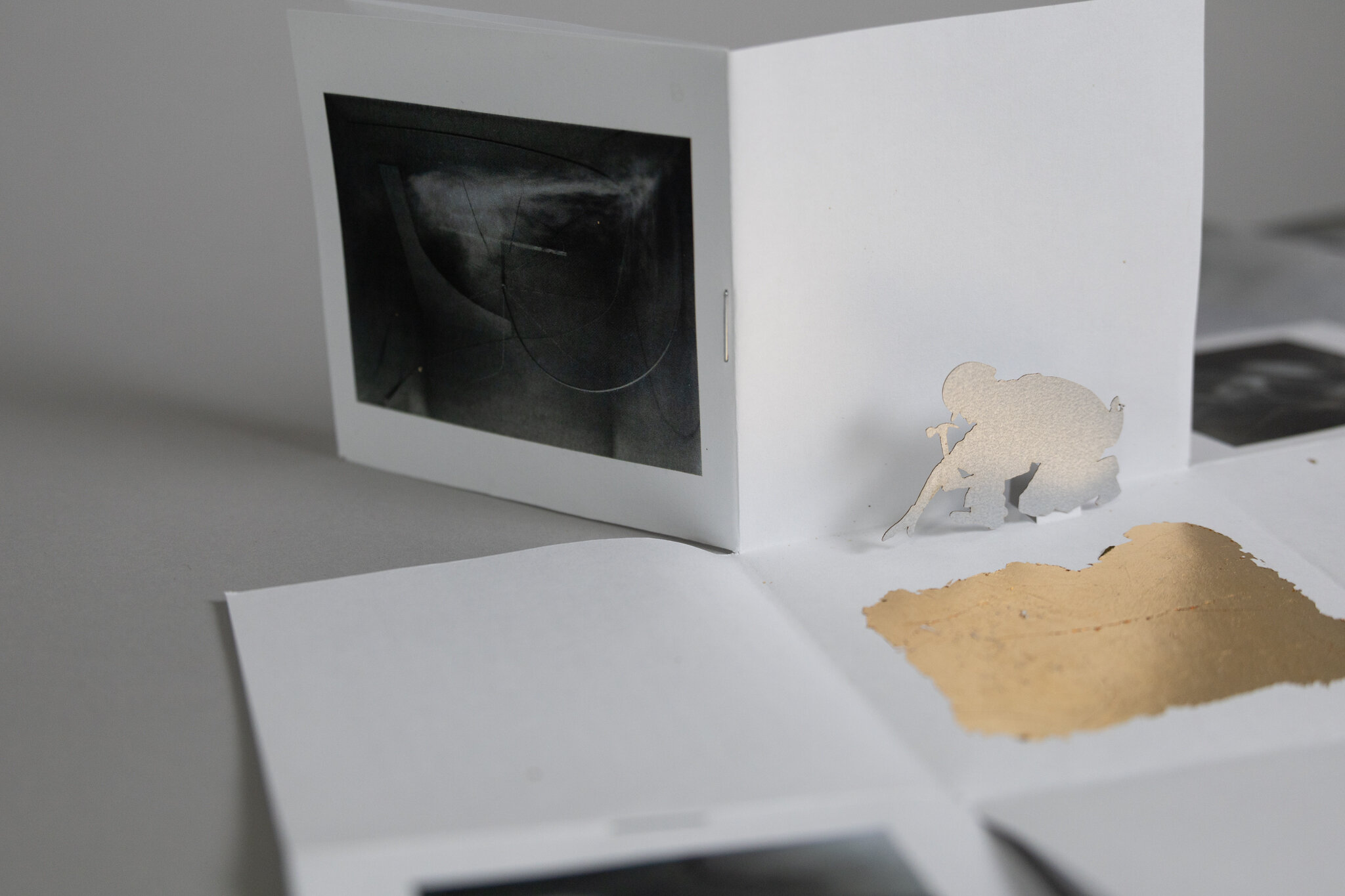

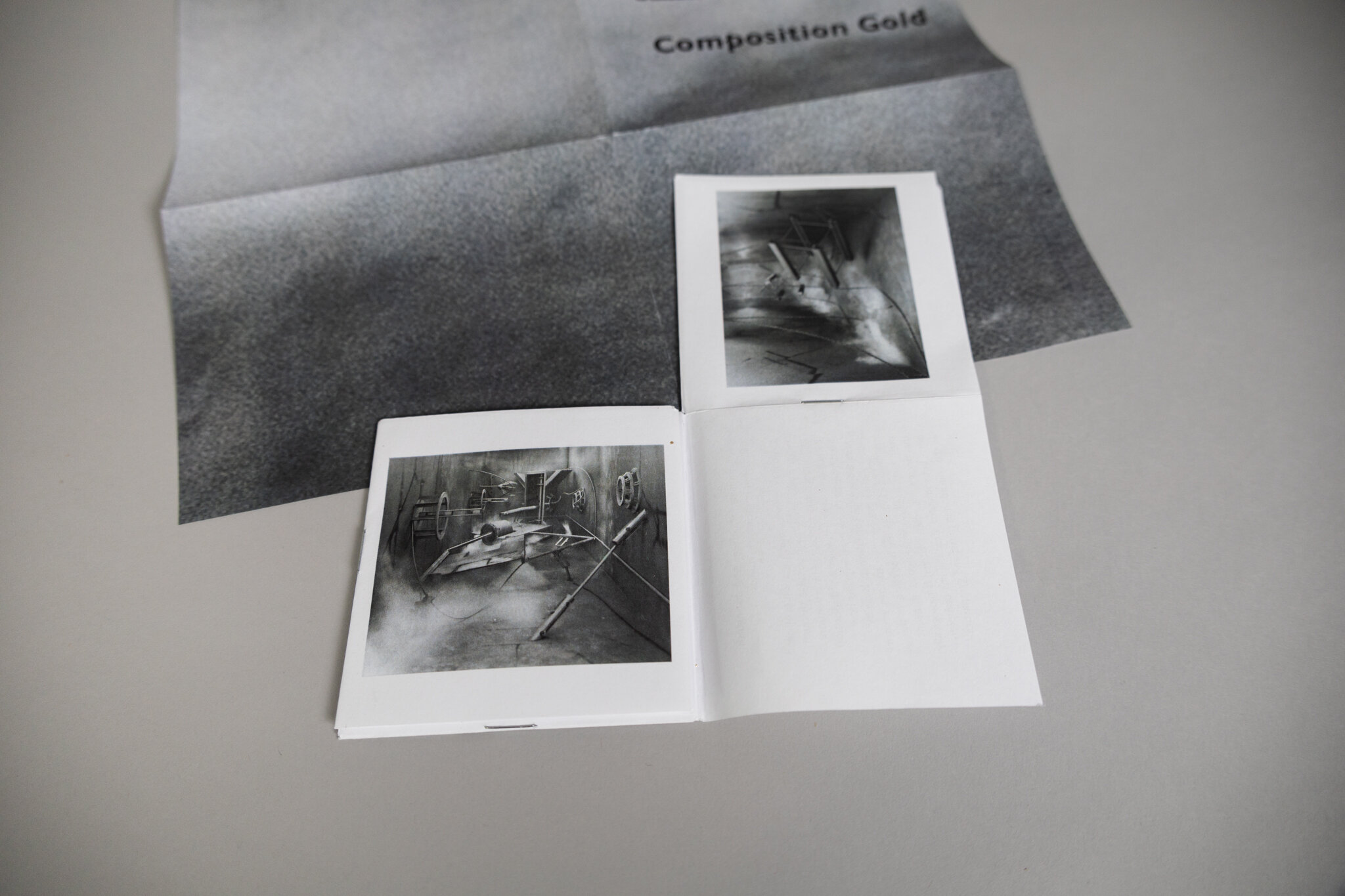

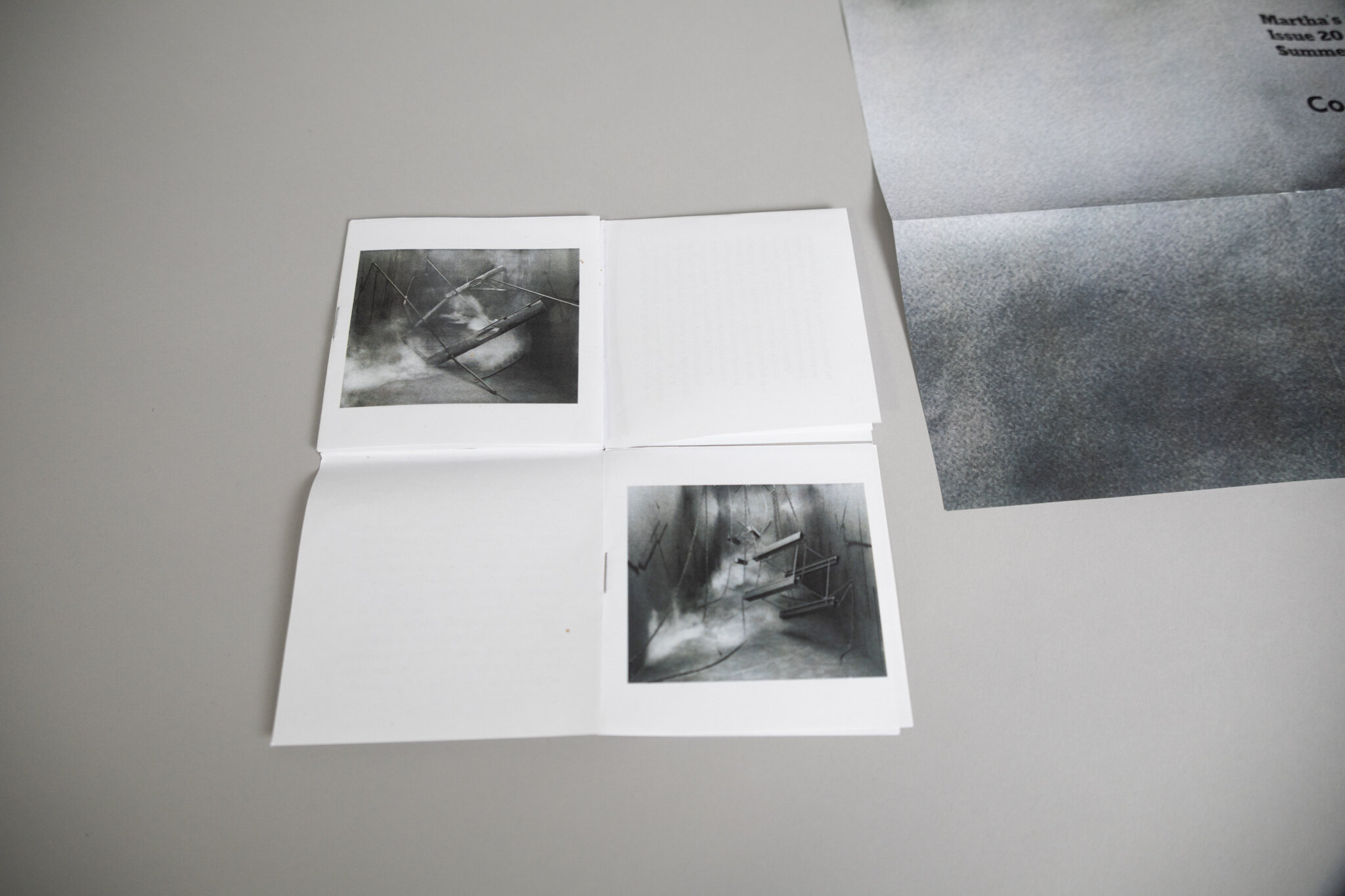

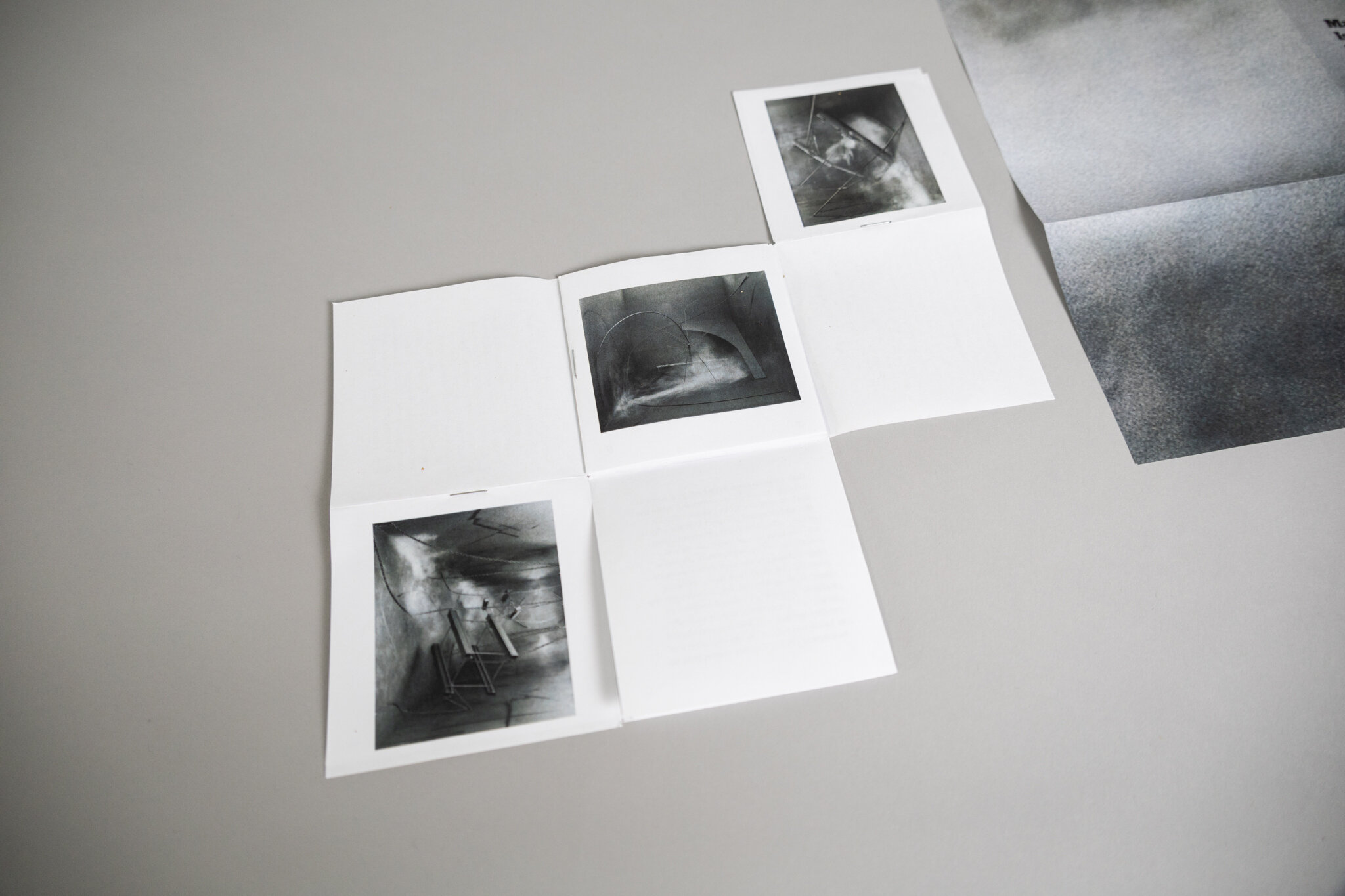

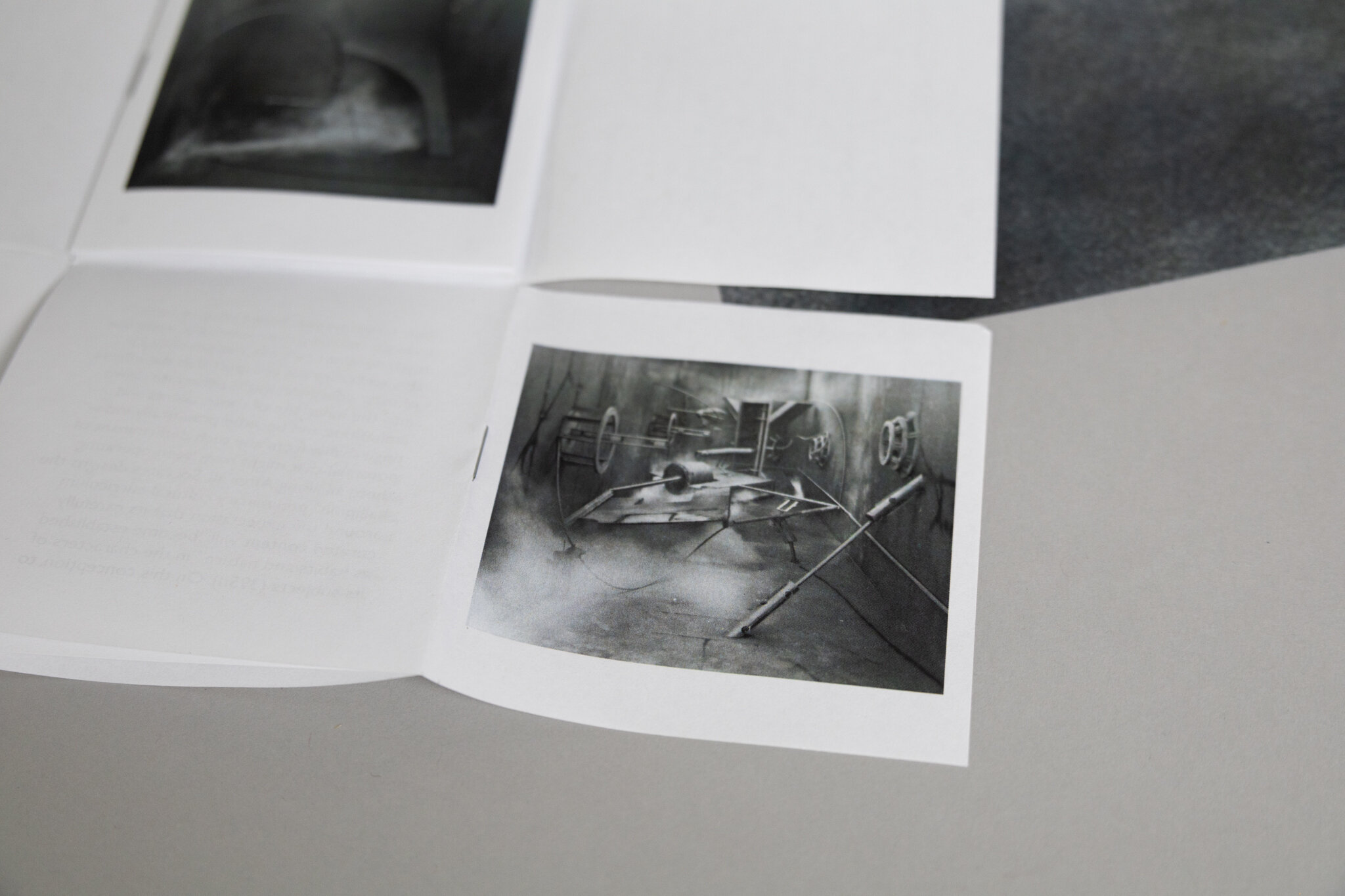

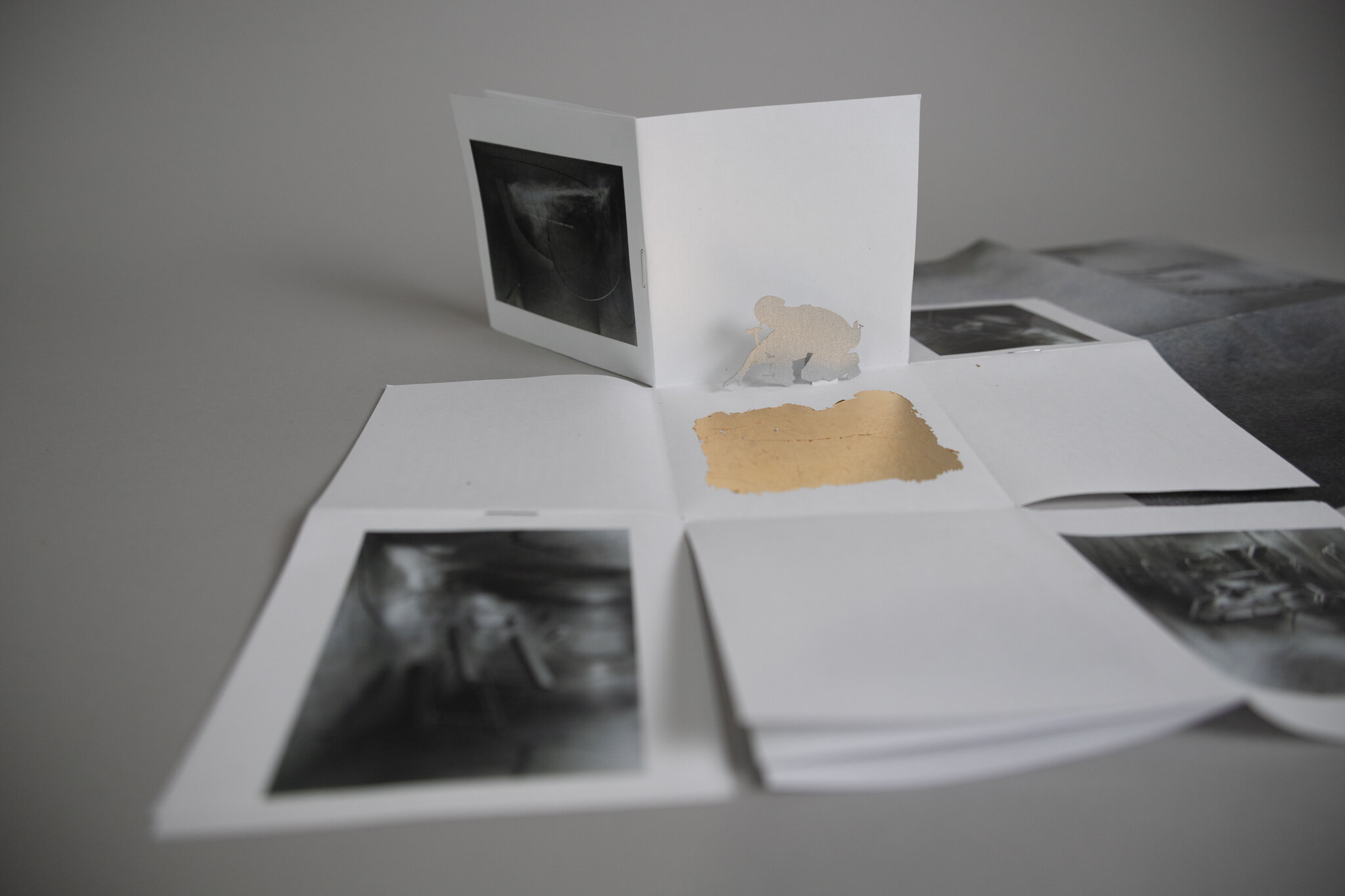

The paper that this introduction is printed on includes a zoomed-in moment of smoke that threads Rodrigo Venezuela’s photographs. Enclosed in this paper fold is another piece of paper that presents four of Venezuela’s fantastic photographs, featuring geometric sculptures suspended, dangling, and finding balance in a space smudged with grey and the air infused with ever-present smoke. Is this smoke the steam of labor? Are the objects the leftover tools and sites of a place that laborers have left? Or are the objects proxies for laborers themselves, finding rest in an environment that is difficult to breathe in? On the one hand, the pictures conjure fantasies about the industrial age–the momentum of factories transforming metals into all kinds of useful objects that ultimately benefit the ruling or capitalist elite. But, in another way, and maybe simultaneously, Venezuela’s pictures foreshadow a future where we are invited to imagine new environments for work that could be better or worse than what we have seen.

This brings me back to my first distinction between the definitions of nobility and the malleability of nobility when it comes to the perception of morality. As you open Venezuela’s photographs, the words of Keum’s essay appear through the smoke until the silhouette of a silver laborer is seen hammering the ground. The “ground,” also the last page of the pamphlet, features a piece of composition gold, as if the silver man is trying to mine something that seems valuable but is actually a mixture of unspecial minerals. The way you open this book mimics a person's emergence from the moment of birth in Keum’s essay; considering that “birth” may occur after one’s primary education, Venezuela’s pictures present the place of one’s birth as a place of imagined labor. What does nobility mean to a laborer? What do work and merit mean to a hereditary ruling elite?

Our current pandemic and global geopolitical reality has brought to light how people shape gestures in an effort to appear noble, even when such actions or expressions may be shallow or even malicious. On August 30, 2021, the United States Armed Forces finished their withdrawal from Afghanistan, an act that was framed by President Biden in his speech the following day as an “extraordinary success.” But this language does not mirror the vast skepticism of the U.S.’s withdrawal method and its overall project in the Middle East over the last several decades.

Composition Gold, the title of this issue, is metal leaf that looks like gold but is actually made from a mixture of brass, copper, and zinc. It is used to illuminate the grand ceilings of esteemed buildings, such as train stations, banks, and government centers. It is used as a display of nobility and “extraordinary success.”

- Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Martha's Quarterly

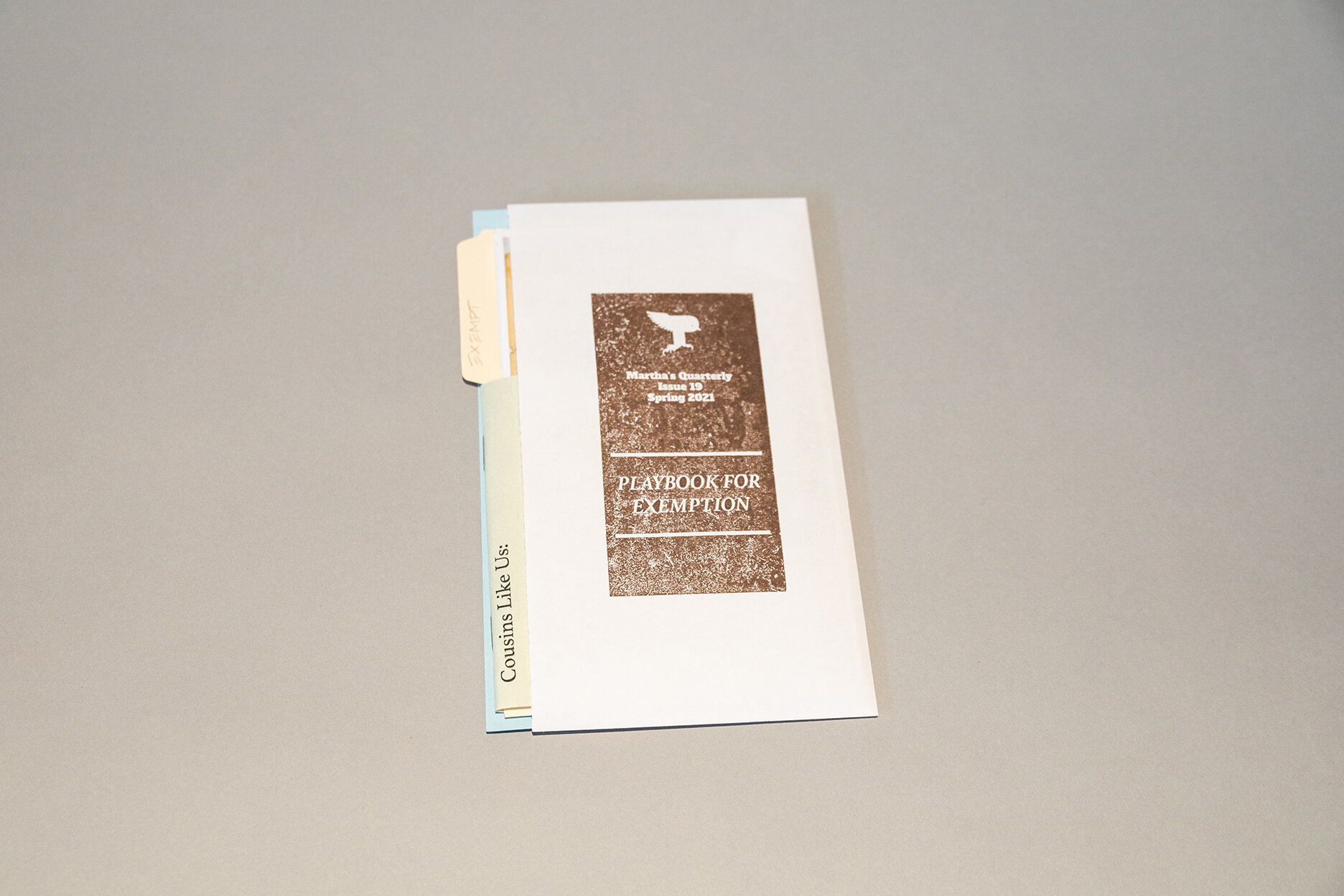

Issue 19

Spring 2021

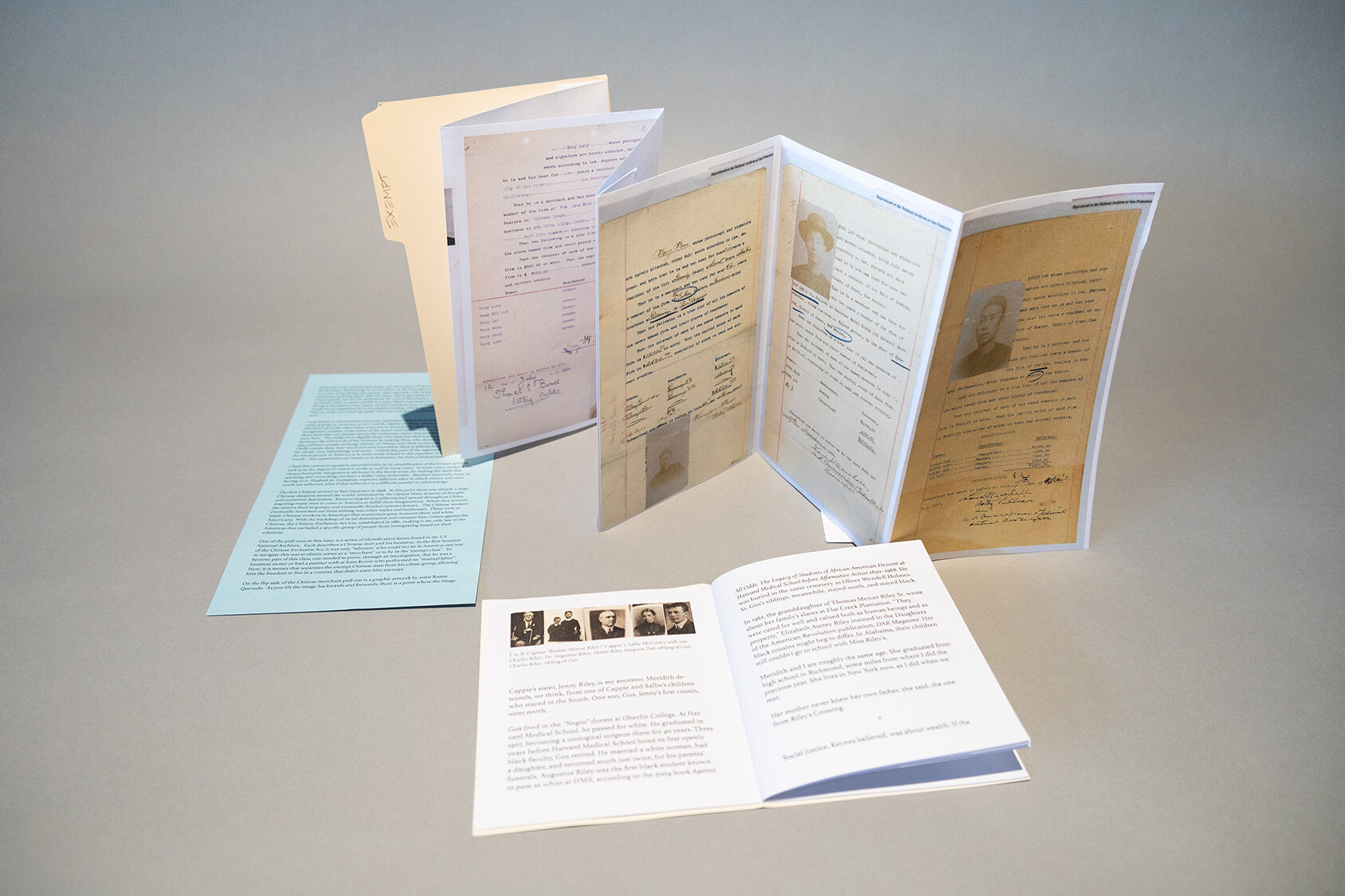

Playbook for Exemption

8.5” x 5”

About the contributors:

Taylor Beck is a writer & a teacher based in Westport, CT. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The L.A. Review of Books, The Washington Post and other publications.

Ronny Quevedo’s artistic practice is an examination of the vernacular languages and aesthetic forms generated by displacement, migration, and resilience.

Alchemy is the ancient philosophy, art, and science of transforming base metals into gold. Sci-fi author Ted Chiang, in an interview on the Ezra Klein Show, explained:

“[...] One of the things that people often associate with alchemy is the attempt to transmute lead into gold. And of course, this is appealing because it seems like a way to create wealth, but for the alchemists, for a lot of Renaissance alchemists, the goal was not so much a way to create wealth as it was a kind of spiritual purification, that they were trying to transform some aspect of their soul from base to noble. And that transformation would be accompanied by some physical analog, which was transmuting lead into gold. And so, yeah, you would get gold, which is cool, but you would also have purified your soul.”

I was drawn to this statement because capitalism creates an intimate bond between the value of gold, or currency, to one's worth, dignity or virtue, all related to one’s soul. We see this bond all of the time: when someone is rewarded for their merit, the award or recognition consists of the name of the honor and money; when a natural disaster strikes, those from afar can donate money for numerous causes that promise to help those who were hurt. This helps to re-dignify those who have lost their homes and possibly increases the self-worth of the virtuous by making those who donate feel better. Every day, ordinary people exchange money on Venmo, and their social networks can see it. Fluffy emojis show how much love and friendship there is behind the exchange of money for meals, rent, babysitting, and more. I think that part of the argument for reparations for black people in America is in some sense related to this equation of money and one’s worth-- that reparations are meant to re-humanize the hurt communities.

I find this common equation uncomfortable in its simplification of the human spirit as well as to the degree in which it works so well in many cases. In some ways, money is the closest humanity has gotten to alchemy in the literal sense, by making the myth that anything and everything can have a dollar value believable. Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 19, Spring 2021, Playbook for Exemption, explores different ways in which money and one’s worth are reflected, even if that reflection is a difficult parallel to acknowledge.

The first Chinese arrived in San Francisco in 1848. At this point there was already a large Chinese diaspora around the world, motivated by the Opium Wars, seasons of drought, and economic depression. Rumors of gold in California had spread throughout China, inspiring many men to come to America to fulfill their imaginations. When they arrived, the miners lived in groups and eventually flooded customs houses. The Chinese workers eventually branched out from mining into other trades and businesses. There were so many Chinese workers in American that resentment grew between them and white Americans. With the backdrop of racial disimination and constant hate crimes against the Chinese, the Chinese Exclusion Act was established in 1882, making it the only law in the Americas that excluded a specific group of people from immigrating based on their ethnicity.

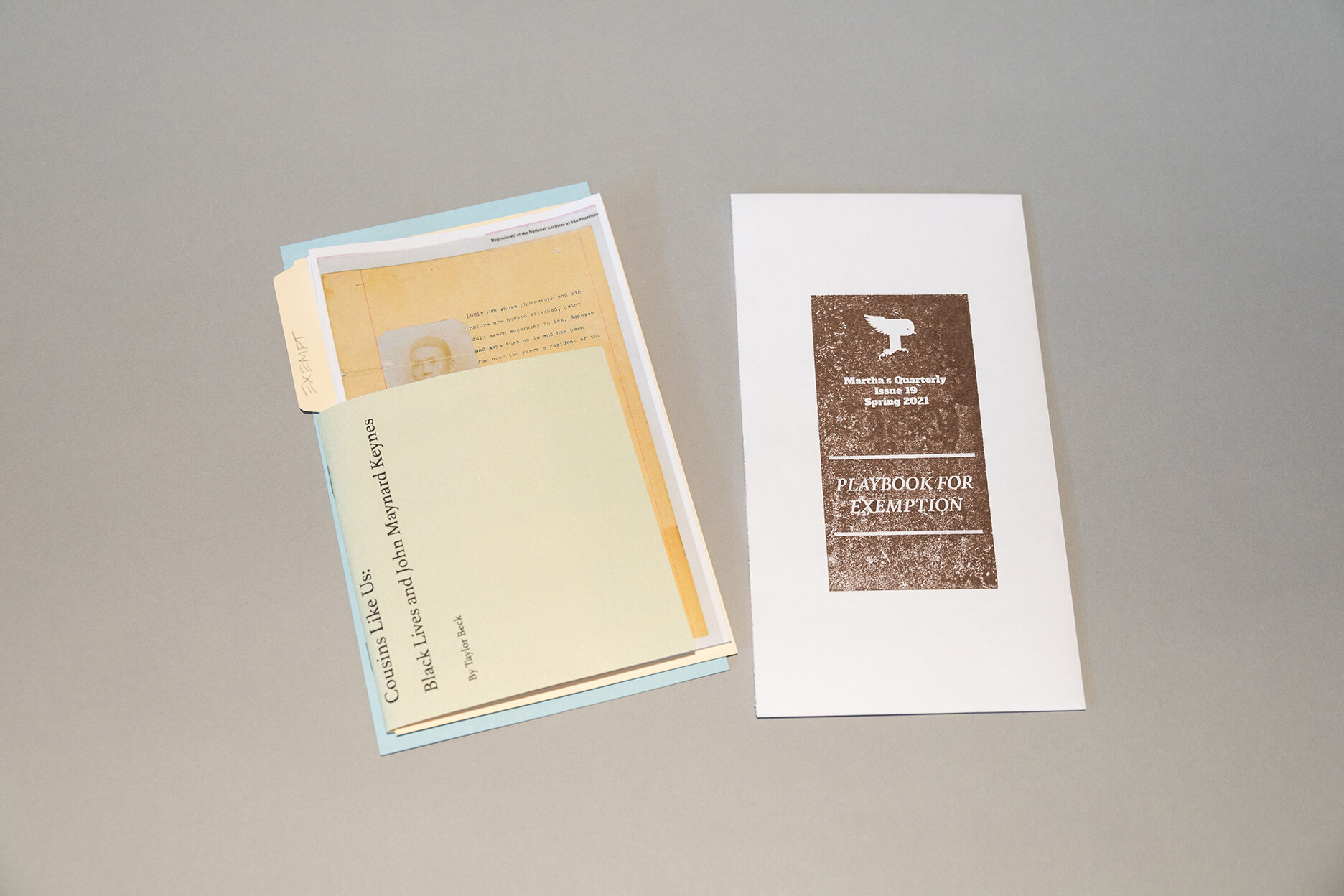

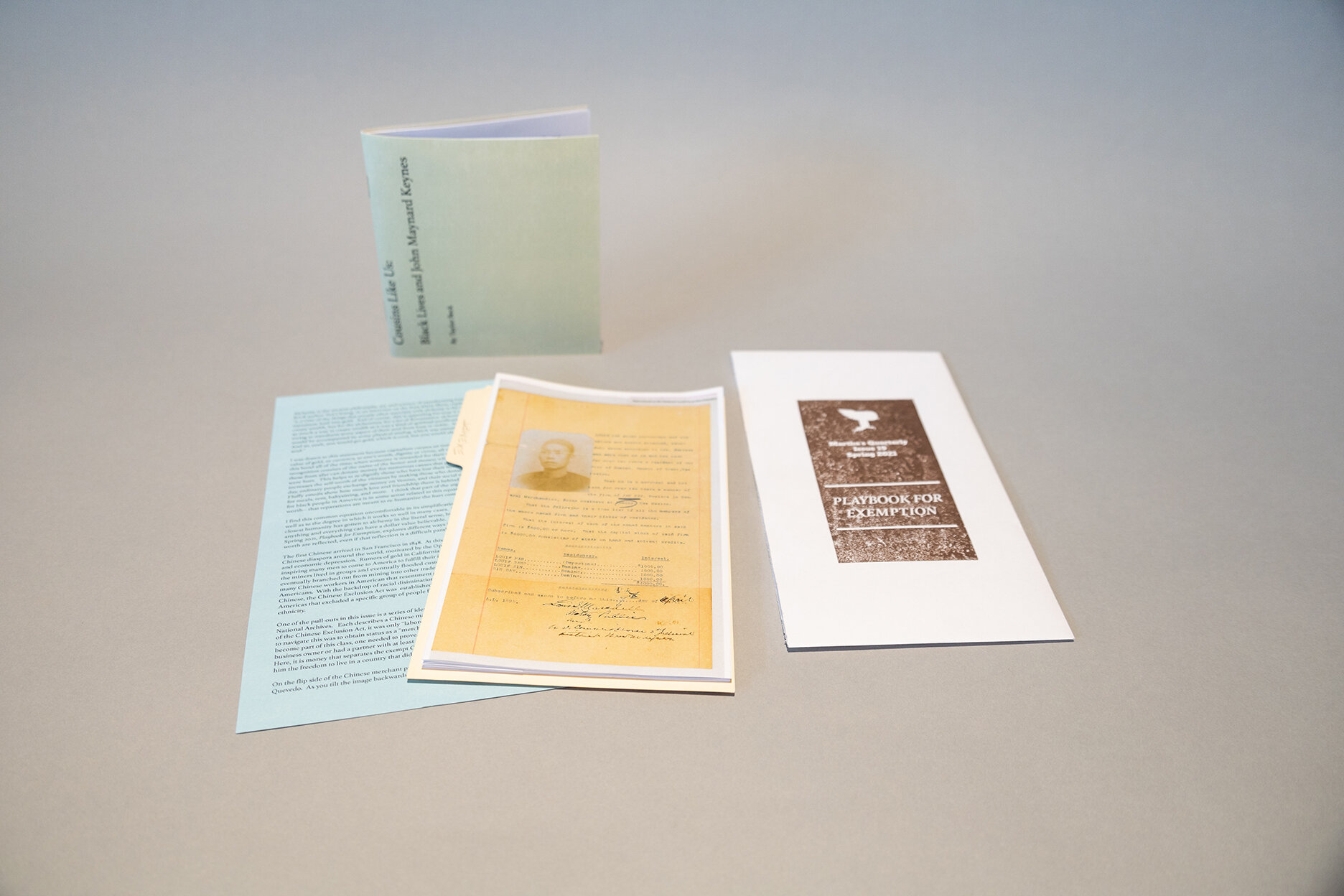

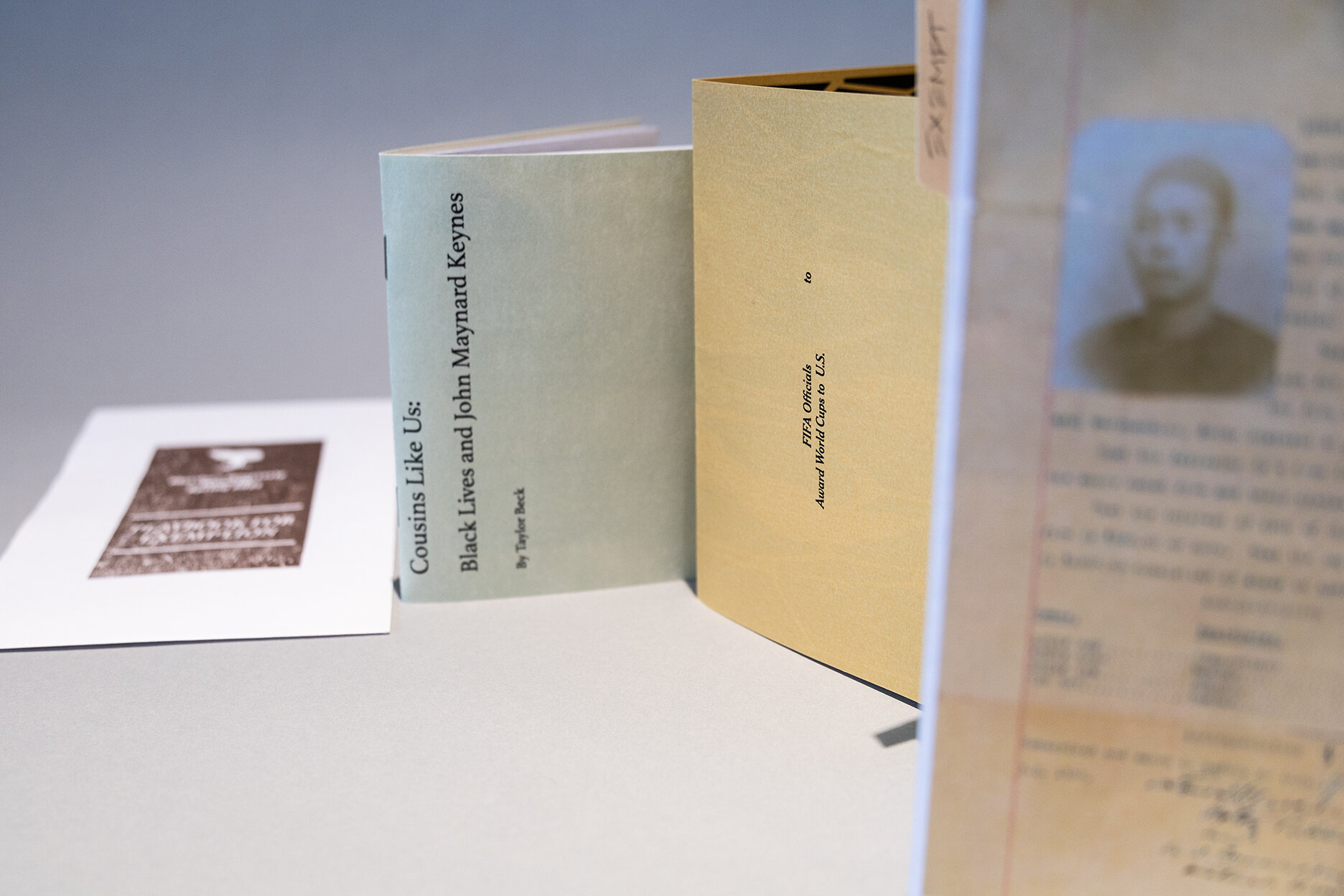

One of the pull-outs in this issue is a series of identification forms found in the US National Archives. Each describes a Chinese man and his business. In the first iteration of the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was only “laborers” who could not be in America; one way to navigate this was to obtain status as a “merchant” or to be in the “exempt class”. To become part of this class, one needed to prove, through an investigation, that he was a business owner or had a partner with at least $1,000 who performed no “manual labor”. Here, it is money that separates the exempt Chinese man from his ethnic group, allowing him the freedom to live in a country that didn’t want him anyways.

On the flip side of the Chinese merchant pull-out is a graphic artwork by artist Ronny Quevedo. As you tilt the image backwards and forwards, there is a point where the image becomes two perfect soccer balls with a map of the world on it. This is the FIFA logo; soccer is one of the most emotionally charged sports in the world. During the World Cup season, you can see many people crying in exaltation or devastation on the streets of many cities around the globe. No other sport brings together as many people as the international fanfare of soccer. I think this unique sport, for whatever reason, is able to allow its fans to project their nation’s dignity: when they see their players play, their country becomes an extension of their personhood, an image worthy of pride.

Soccer and other sports in which people gamble harness the human spirit and its passions to money. Some fans gamble casually with friends; some gamble with dreams of sudden changes in fortune; some gamble to prove themselves. FIFA is a corrupt organization, energized with backdoor deals and bribery. A sport that holds so many people’s ideals for 90 minutes is kept alive by the dealings of greedy individuals and countries. The US was once upset about these backdoor dealings because they did not win the bid to host the 2022 World Cup; as a result, the US District Attorney charged FIFA with bribery. Money in soccer keeps the human spirit alive.

Finally, this Martha’s Quarterly also comes with an essay by Taylor Beck that originally appeared in the LA Times Review of Books last year. While the essay is a review of the book The Price of Peace by Zachary D. Carter, it is much more than simply a synopsis of the book that is about the economist John Maynard Keynes. Cold numbers and statistics can appear to be a safety net for arguments about human lives, dignity and even equity; however, questions of good and evil, justice and injustice, are not simple. Evil is contextual, often created by circumstances like economic inequality, as Keynes knew. Were the Americans who excluded the Chinese in the context of widespread poverty, the Gold Rush, and dreams of sudden changes in fortune necessarily evil? Is it inherently “good” to donate one’s money? Whose dignity is that really about? Money is, and has been, the base metal that we transform into humanity, whether for others or for ourselves.

– Tammy Nguyen

Editor-in-Chief