MQ 2020

Martha's Quarterly

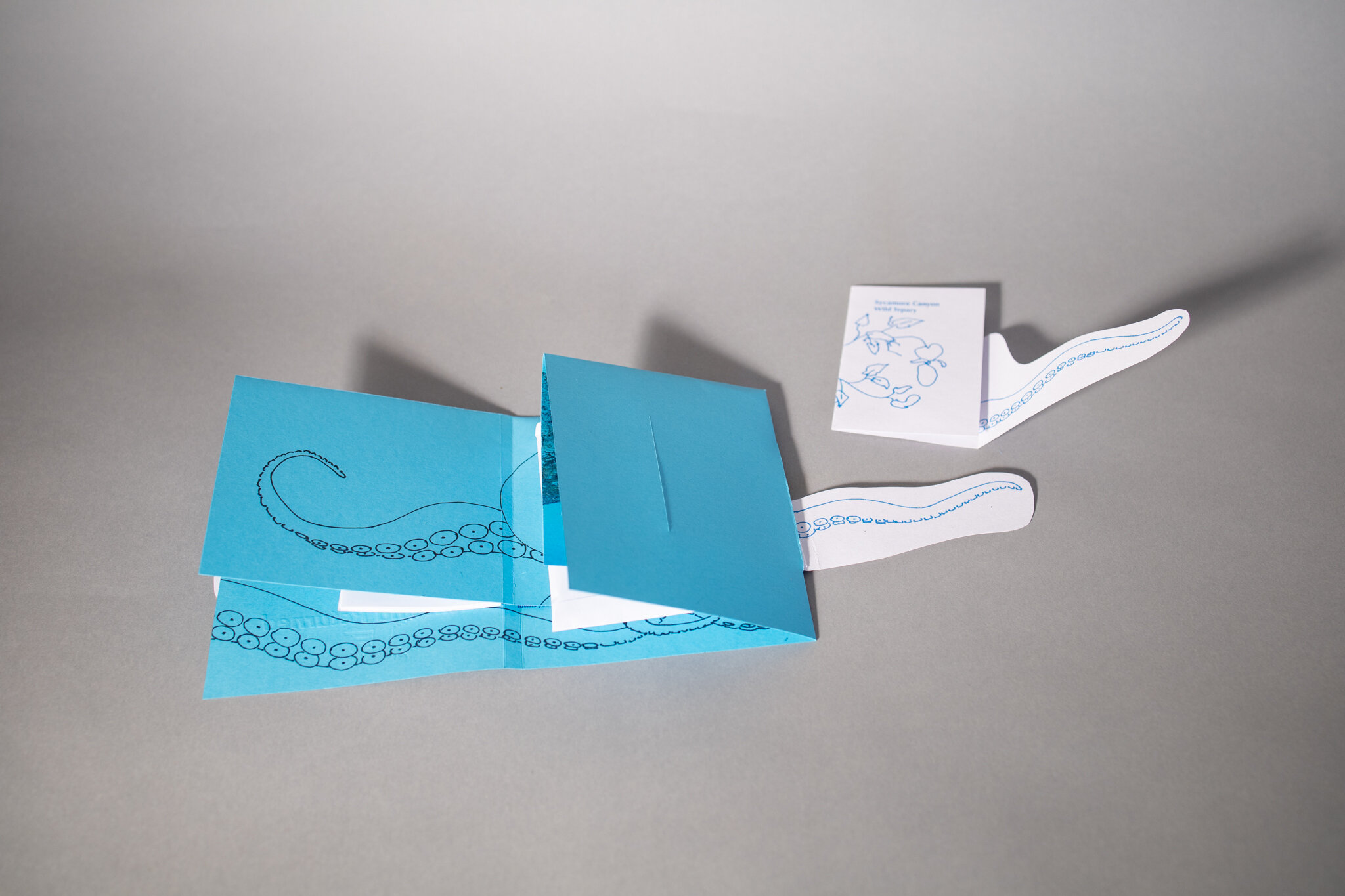

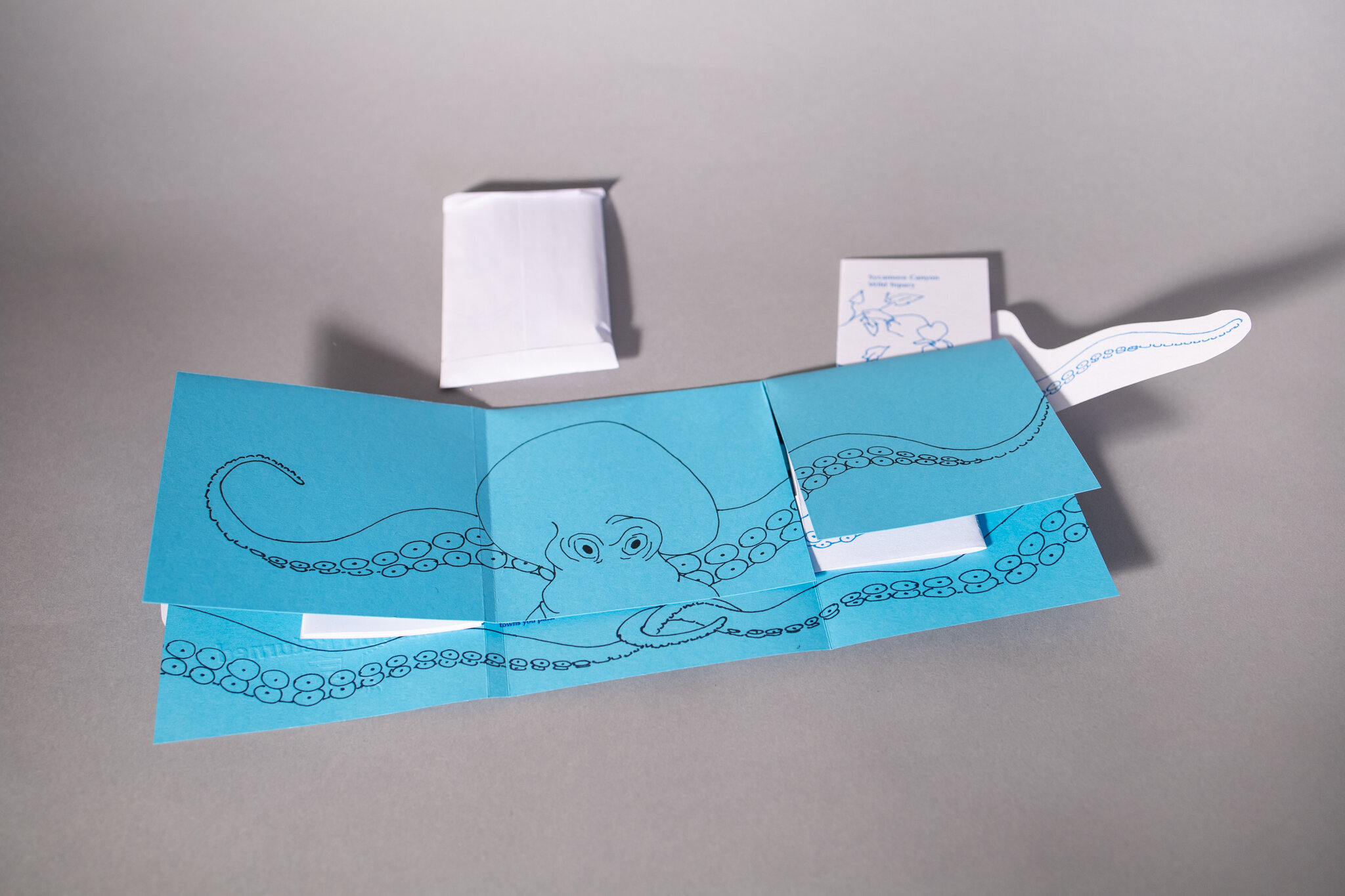

Issue 18

Winter 2020

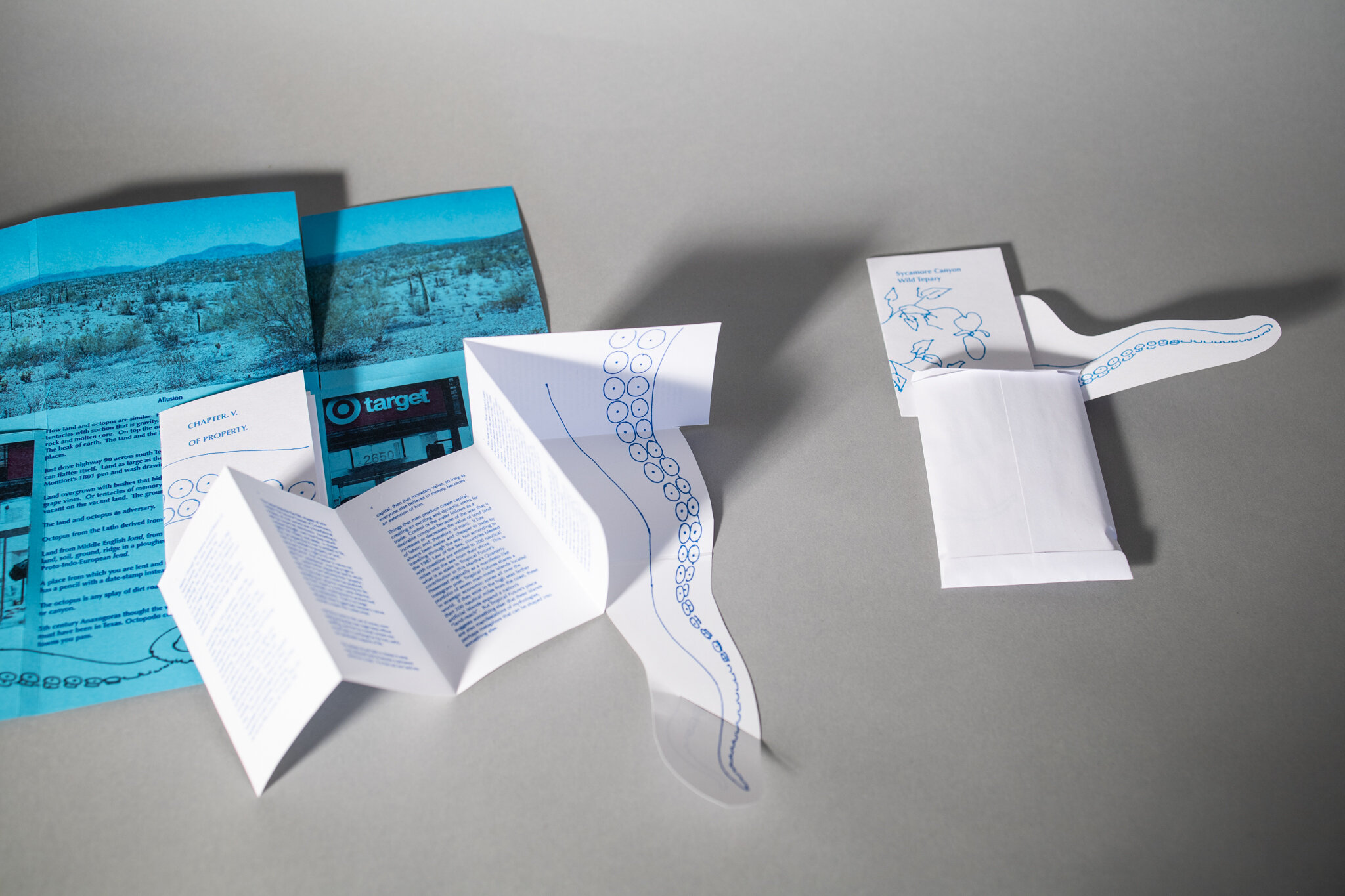

Lent and Returned

5.75” x 5”

About the contributors:

Tropical Futures (TFI) is a multidisciplinary think tank studio founded and operated by Chris Fussner, a Filipino American designer based primarily in Cebu, Philippines and the tropics at large. His focus is on looking towards new ideas, models, practices and communications related to the tropics, as well as crafting and supporting the diffusion of new narratives around this climatic and geographic space that wraps around the world and connects various ecologies and peoples. Chris graduated from the School of Design Strategies at Parsons School of Design.

Diane Glancy is a professor emerita at Macalester College. Her latest book is "Island of the Innocent: a Consideration of the Book of Job," Turtle Point Press, 2020. "A Line of Driftwood: a Story of Ada Blackjack" and a collection of essays, "Still Moving, How the Road, the Land and the Sacred Shape a Life," are forthcoming in 2021.

John Locke was a British philosopher, Oxford academic, and medical researcher often credited as being the “Father of Libertarianism”.

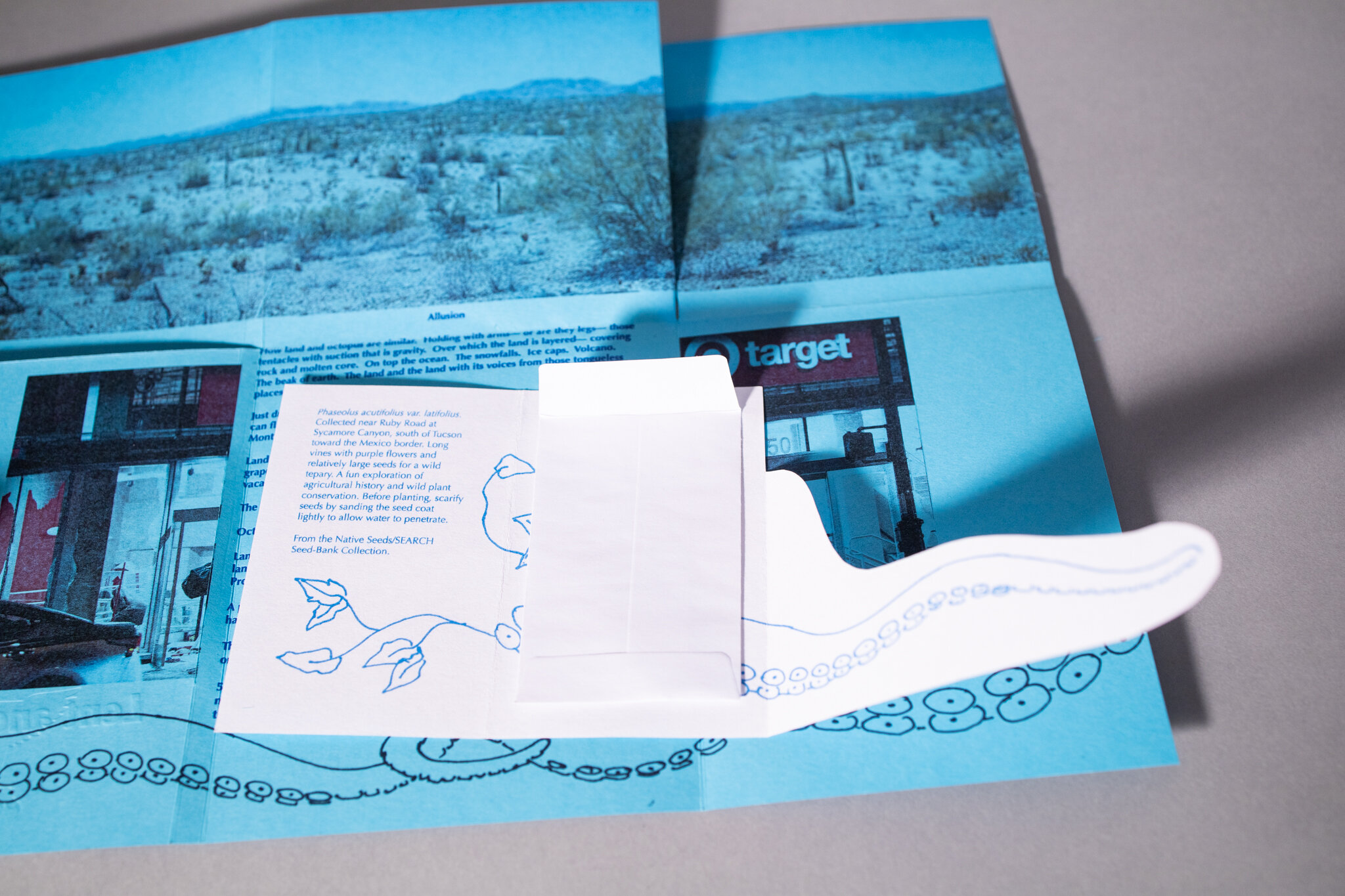

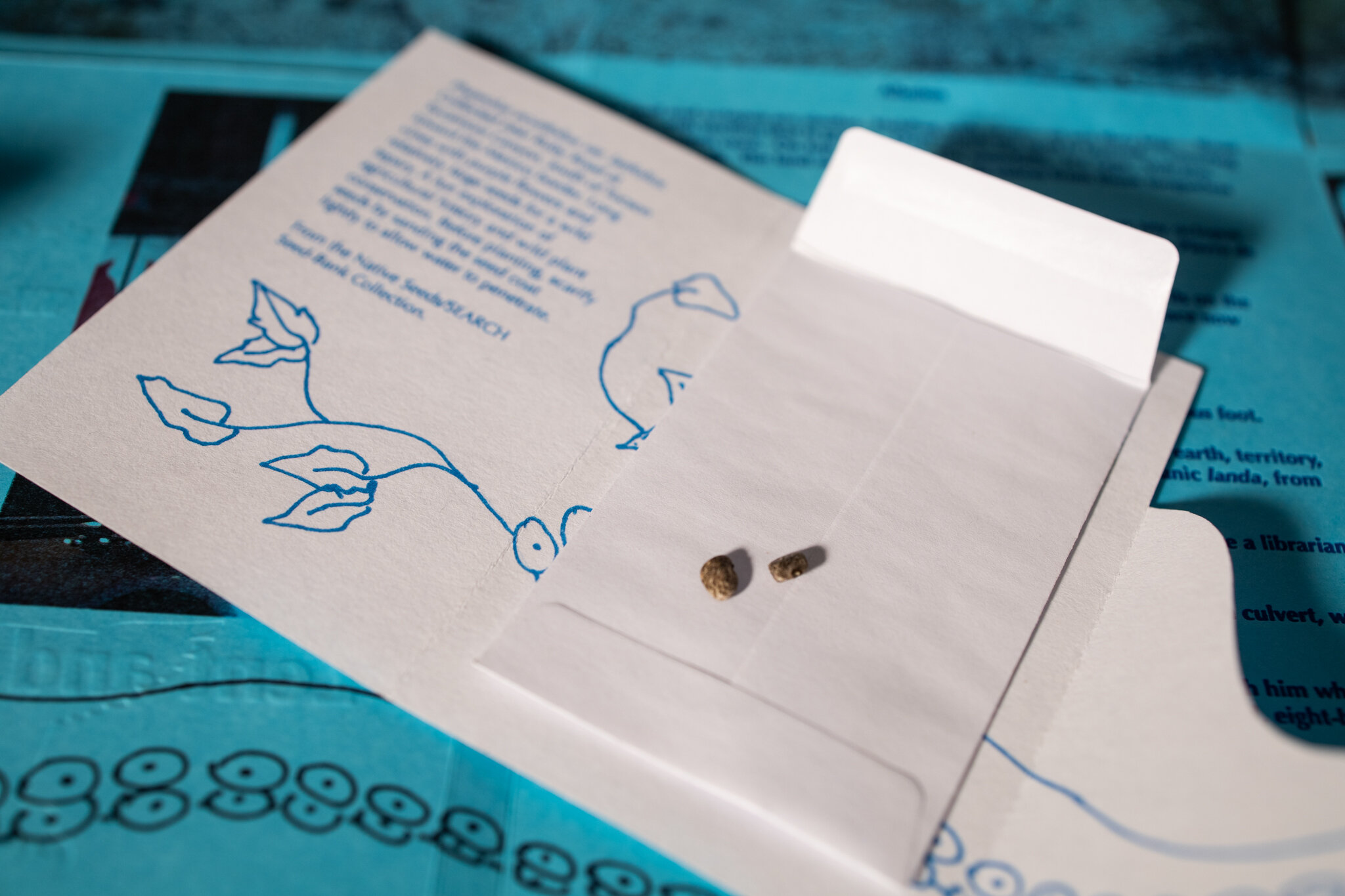

Native Seeds/SEARCH (NS/S) is a nonprofit seed conservation organization based in Tucson, Arizona. Their mission is to conserve and promote the arid-adapted crop diversity of the Southwest in support of sustainable farming and food security.

I write this Winter introduction on the Fall morning of Thanksgiving 2020, and it’s a strange holiday this year. We are still in the midst of a pandemic that seems to be resurging quickly and vigorously. The mainstream news stations have all encouraged Americans to stay home and celebrate with only one’s household, generously showing footage of long Covid testing lines coupled with packed airports. For me, Thanksgiving has always been a joyous holiday. In my childhood, I recall my mom or aunt making a turkey accompanied with delicious Asian food, such as stir fry noodles with packaged ham, sweet corn dessert soup, and egg rolls. This year, my husband and I are making a goose while our newborn kicks around on the floor. Later, we will Zoom with everyone whom we would have been with, and surely someone will not know how to turn on their camera or microphone, and it will be endearing.

Thanksgiving, though, is a complex holiday. It’s a day to give thanks for all that we have and, more traditionally, for the bounty of food that our land has given us. Our land is a loaded notion. America, of course, was created out of the breathtaking imagination of British colonizers who “manifested their destiny” through the massive annihilation of Native peoples. For many American immigrants, this land possesses the mythology that it can also be our land; that our land is so expansive that it can hold all of our imaginations. This issue of Martha’s Quarterly一 Issue 18, Winter 2020: Lent and Returned一explores how land holds mankind’s imagination and, by extension, allows our lives to live longer as legacies.

Around May of this pandemic, when the protests for Black Lives Matter were at their peak, I was intrigued by the collisions between folks on the opposing sides of the rioting and looting. On the one hand, some people were in defense of the looters, exclaiming: “We have had it. There is no more social contract. The rioting and looting is a reflection of the government’s abandonment of basic human rights and dignity for Black lives.” On the flip side, some people exclaimed: “Looting and rioting is not the answer. These are people’s business, their properties; these are their lives.” One point of intrigue for me was how businesses and properties were being equated to human lives. Of course, they are not; but are they a proxy for human life?

This issue features the fifth chapter of John Locke’s The Second Treatise of Government, a theory of civil society and a foundational text for American democracy. According to Lockean thought, men have three natural rights: life, liberty, and estate. In chapter five, he argues that if man is entitled to life, then he is entitled to property, or land, because he has a right to his own ‘preservation’; that whatever in nature can give him ‘subsistence’, man has a right to that. Locke further argues that land in which men labor in turn becomes their ‘property’; this is because man’s work has produced something of value for maintaining his life. But then, there is a twist: Locke notes that, for example, working land to produce food has a temporality. Food is no longer valuable when it goes bad, because it cannot nourish a man’s life. Locke writes:

And thus came in the use of money, some lasting thing that men might keep without spoiling, and that by mutual consent men would take in exchange for the truly useful, but perishable supports of life.

The advent of and faith in money in some ways allowed land to become a permanent proxy for a man. If a man can turn land into capital, then that monetary value, so long as everyone else believes in money, becomes an extension of him.

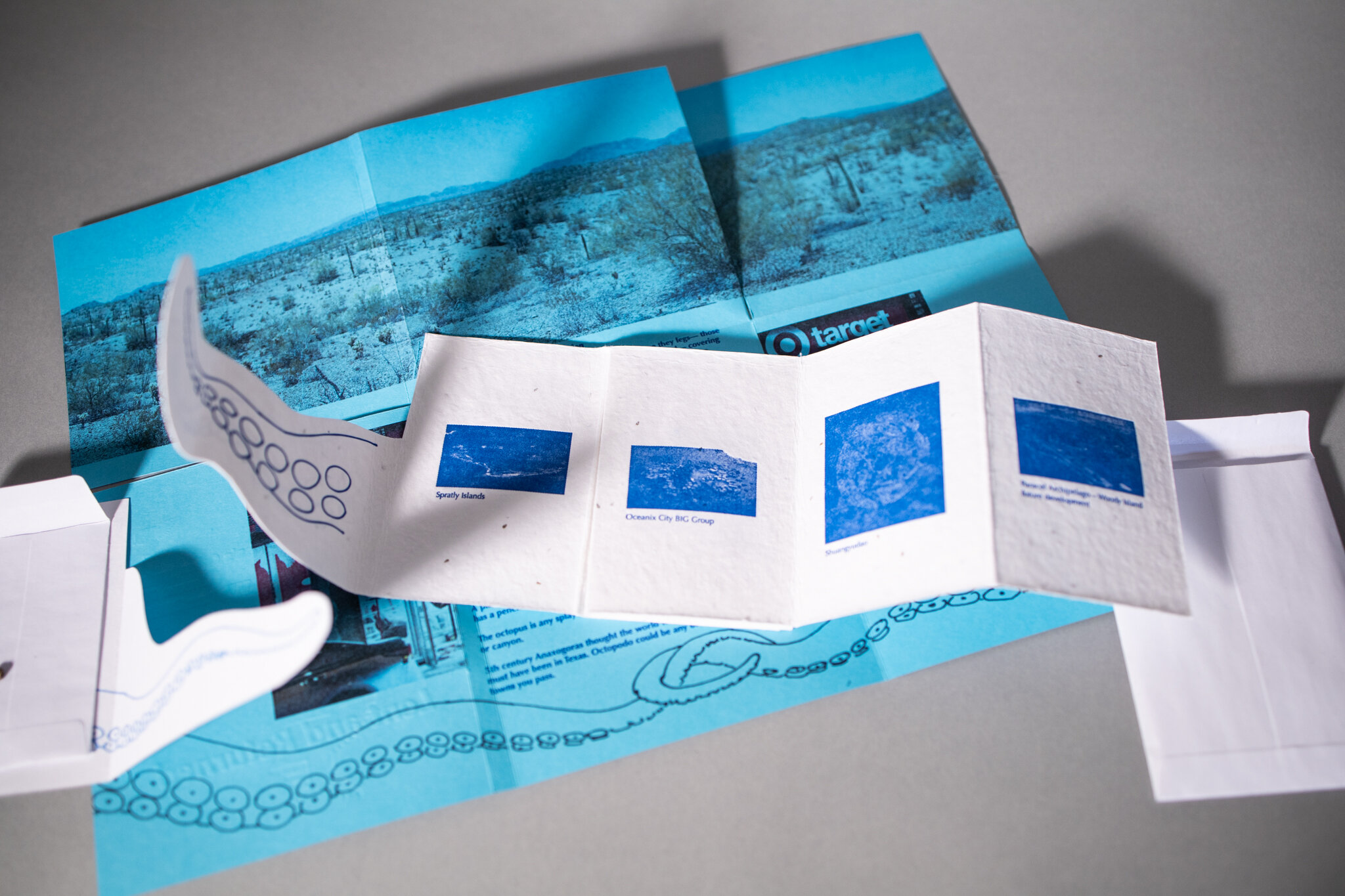

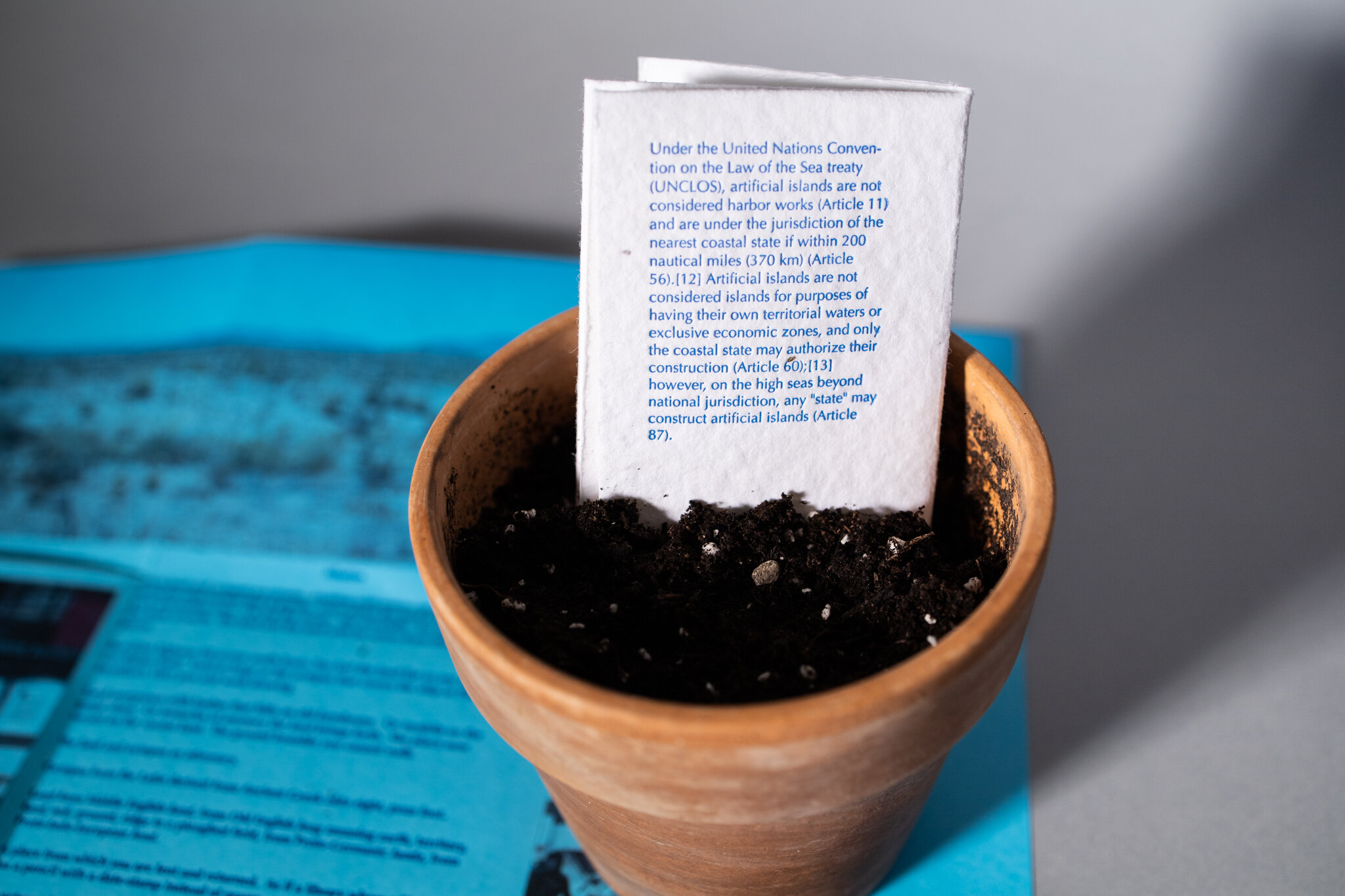

Things that men produce create capital, creating an exciting and dynamic arena for trade. Control of the water follows as a desirable conquest because of the way that it increases or decreases the value of land (and of labor; and, therefore, of man). It has always been easier and cheaper to trade by traveling through the sea, but according to the 1982 Law of the Sea, countries blessed with coastline are entitled to 200 nautical miles into the sea from their shore. This is what is at stake in Tropical Future’s contribution to this Martha’s Quarterly. Presented originally as a manifesto-like Instagram post, Tropical Futures shares a portfolio of seven man-made islands located in strategic economic zones all over the world. If they exist in the high seas farther than 200 nautical miles from the coast, these artificial islands expand a nation’s “land-reach”. But Tropical Future’s piece suggests something else: that these islands are also manifestations of mythologies, perhaps metaphors that can be shaped into something else.

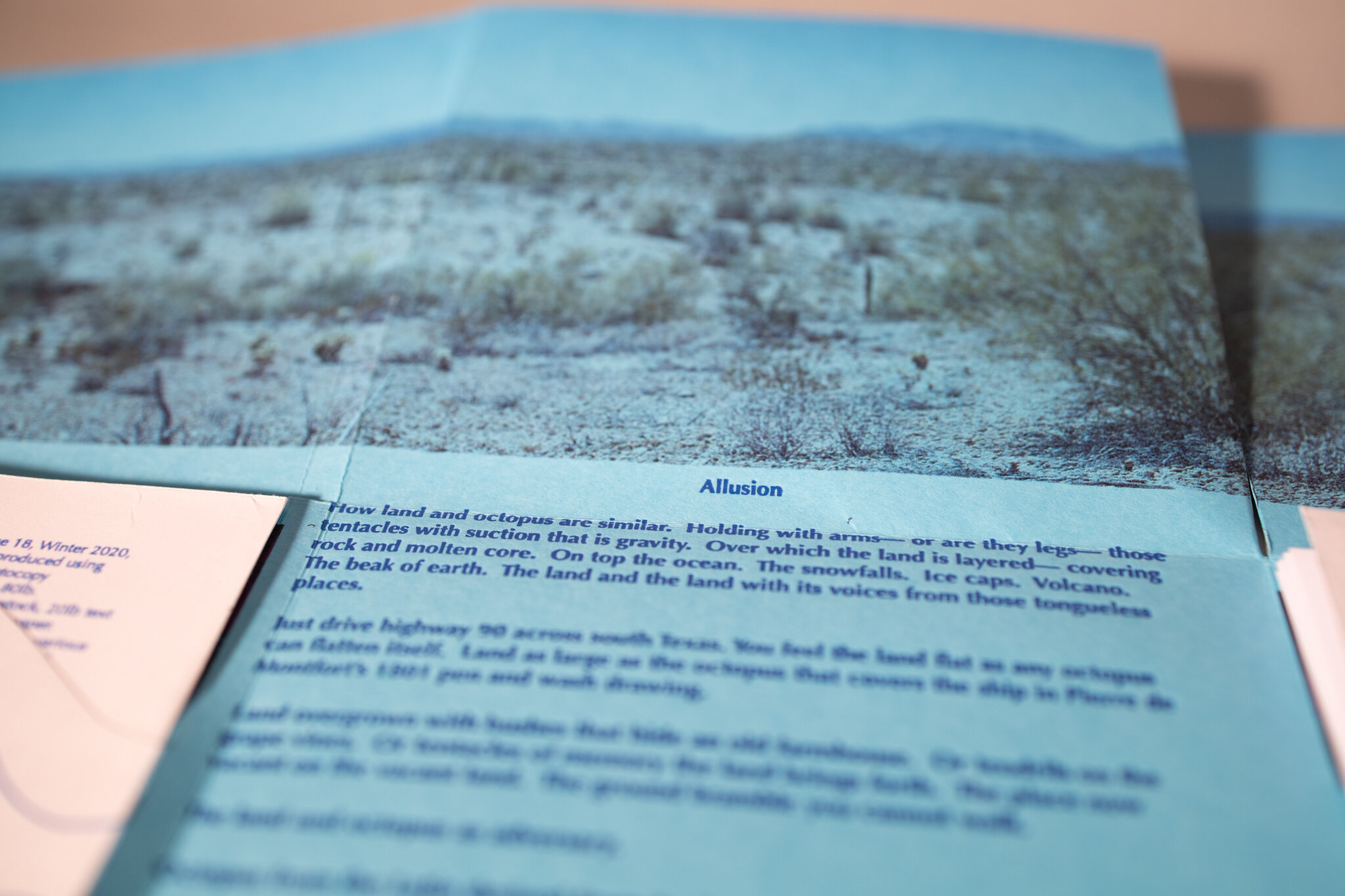

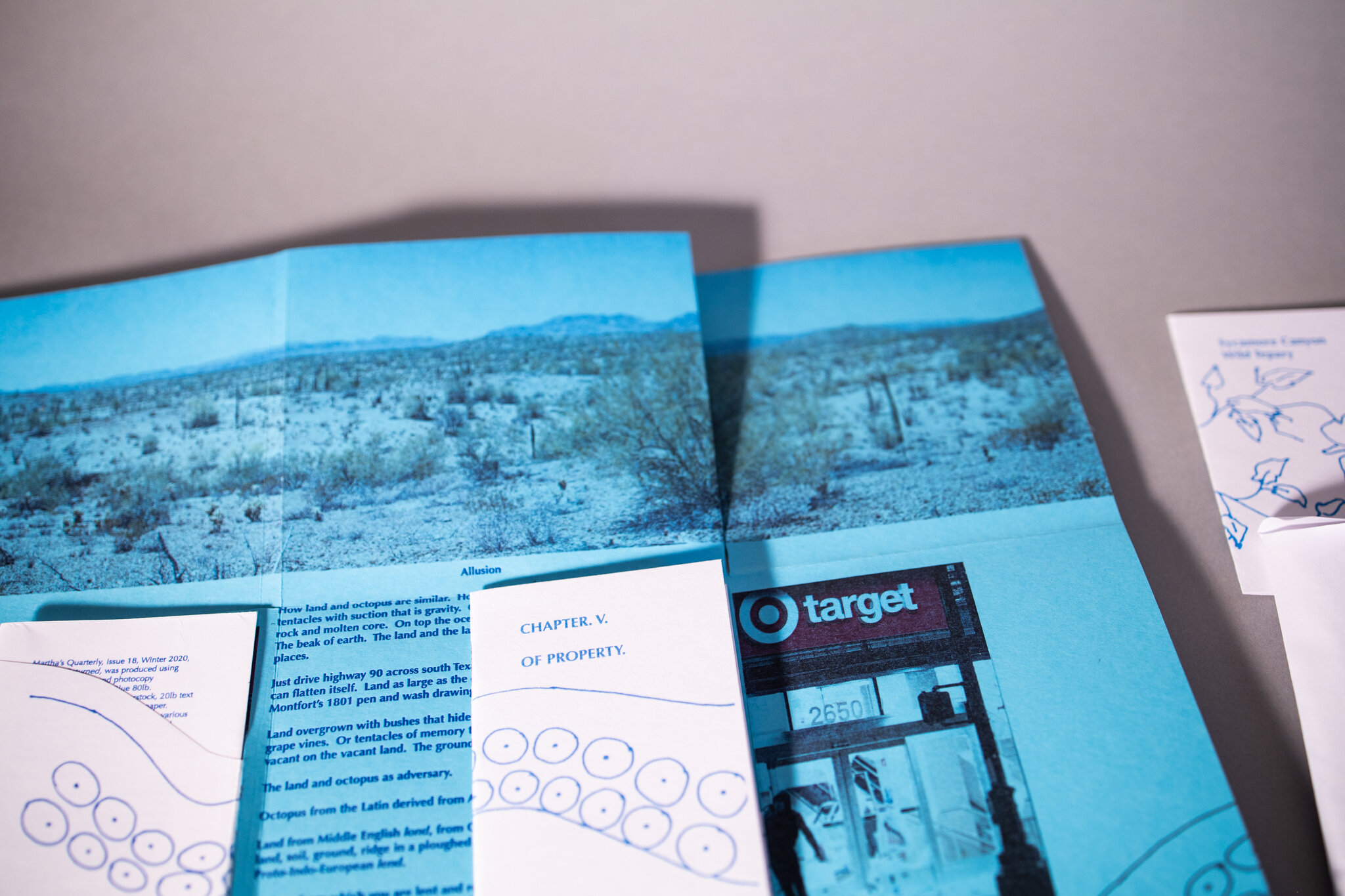

This leads me to Diane Glancy’s poem Allusion, where the poet of English and Cherokee descent forces and then makes true the comparison between land and octopus. Such a metaphor can seem distant, as distant as a metaphor between a human life and something as inanimate as money. Land, Glancy’s poem teaches, is ‘A place from which you are lent and returned.’ As I read this, I think about the octopus that is washed ashore only to slip away with the next tide. But then her poem makes an eerie transition, where the octopus is meshed with the image of buildings in lonely towns. Somehow the sea creature seems lost, the wetness of its vitality drying up. Is there also a drying-up to human life when one tries to live forever in money?

Among many things that this year has made vivid for me, the pandemic has emphasized how temporal life is. It has also demonstrated how life and money are deeply intertwined, and that to merely dismiss the economy as unimportant or unnecessary for human life is misguided. As a species, we all share a communal faith in money. Our belief in the money story's value allows us to provide food and shelter for our families. For many people, the pandemic took away their jobs, preventing them from being able to use their labor to produce nourishment for their families一man’s right to life. And so now, we are at a place of reckoning, as the myth of money is being held against the many lives being lost both in America and globally.

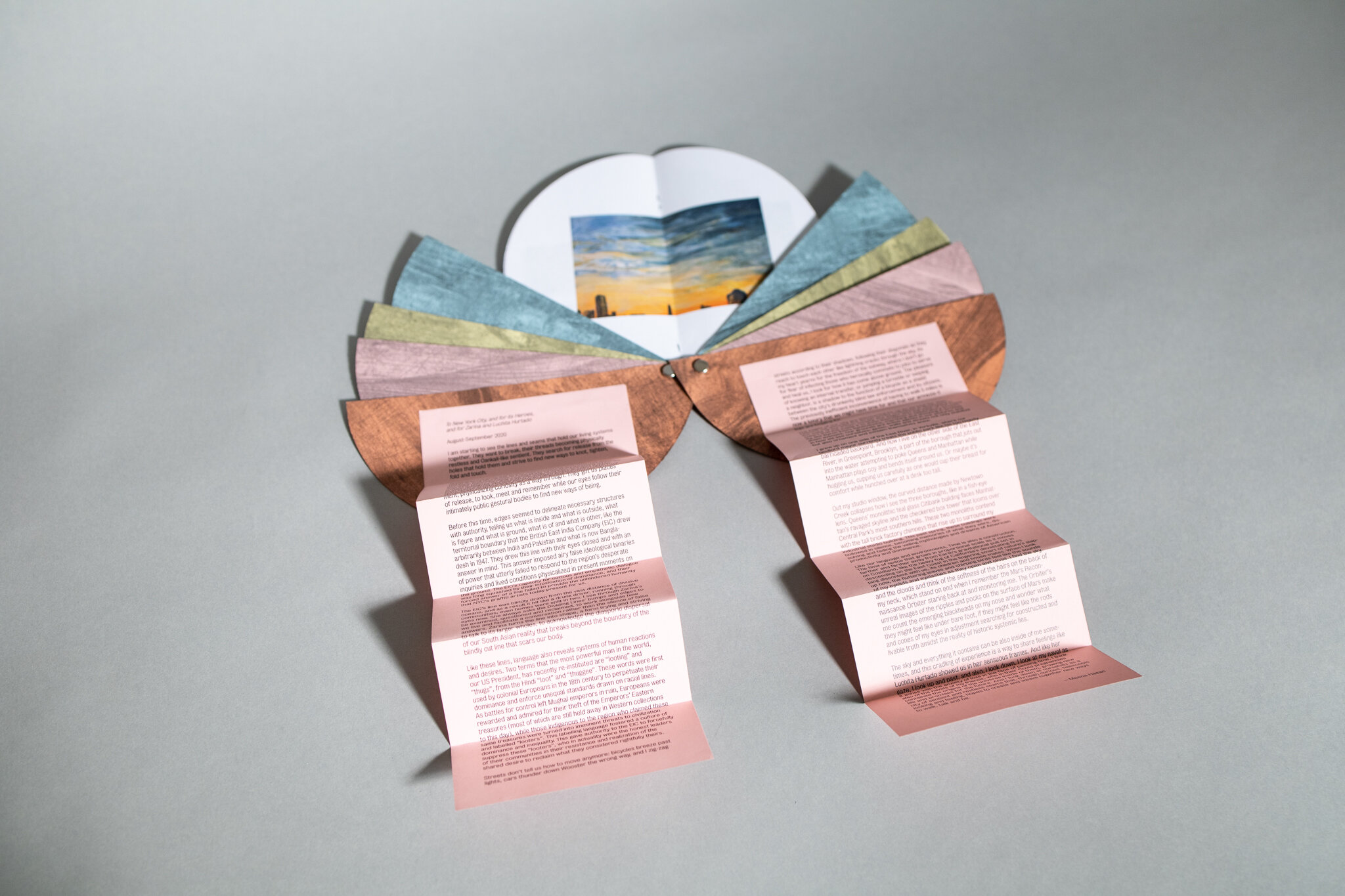

This issue of Martha’s Quarterly also offers you a wild teapry seed native to the Southwest region of the United States. The seed was grown by Native Seeds/SEARCH, a non-profit organization that started in 1983 with the mission to conserve and promote arid-adapted crop diversity in the Southwest. This particular seed is a desert bean that will climb and twine when it becomes a plant. You can plant the seed along with the paper that the artificial islands are printed on, paper that is also implanted with seeds of wildflowers. Perhaps the gesture of planting一a popular hobby of solace during this pandemic一might provide a lively escape from the mythology of our social order that seems so unstable.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Martha's Quarterly

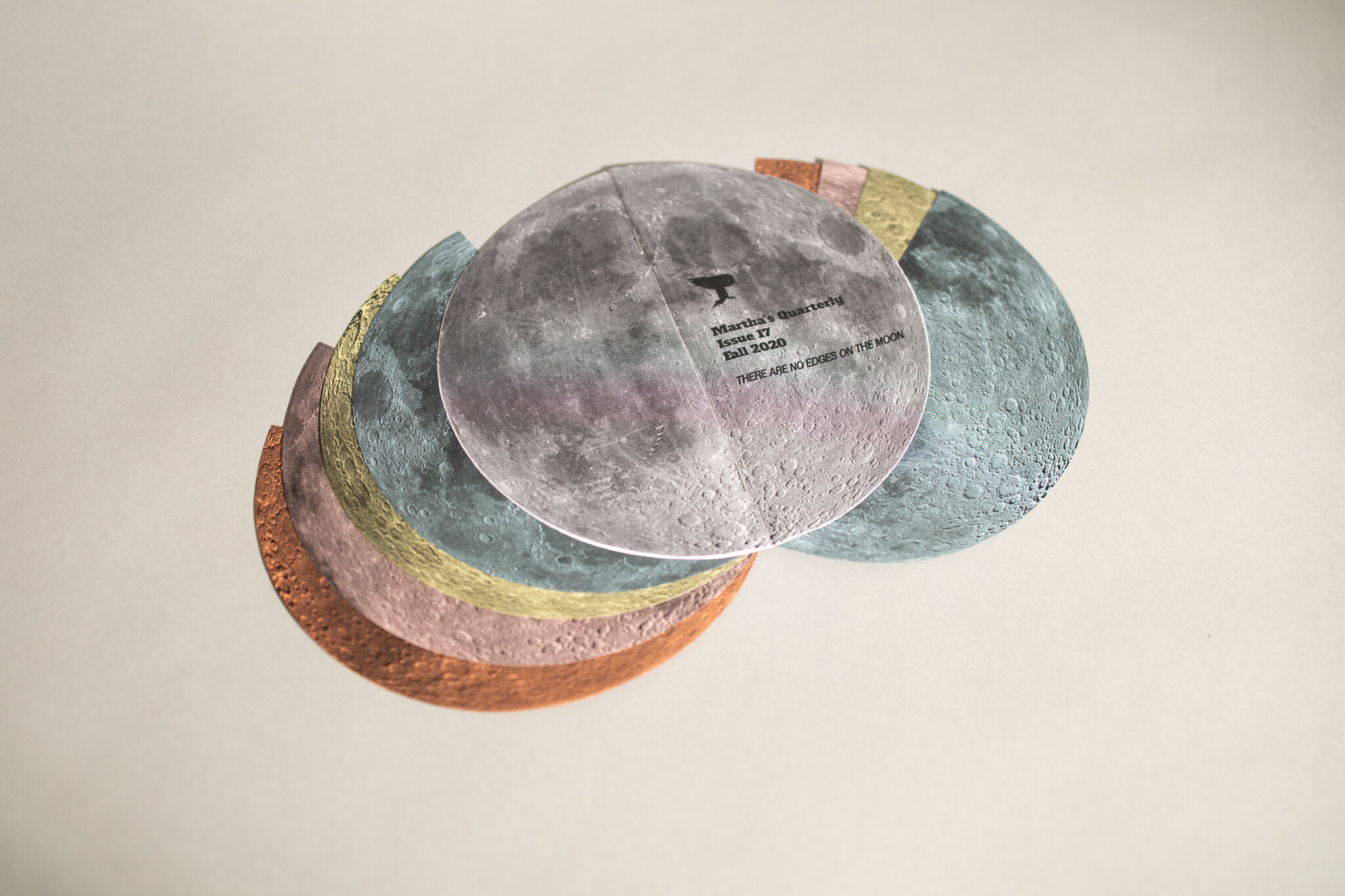

Issue 17

Fall 2020

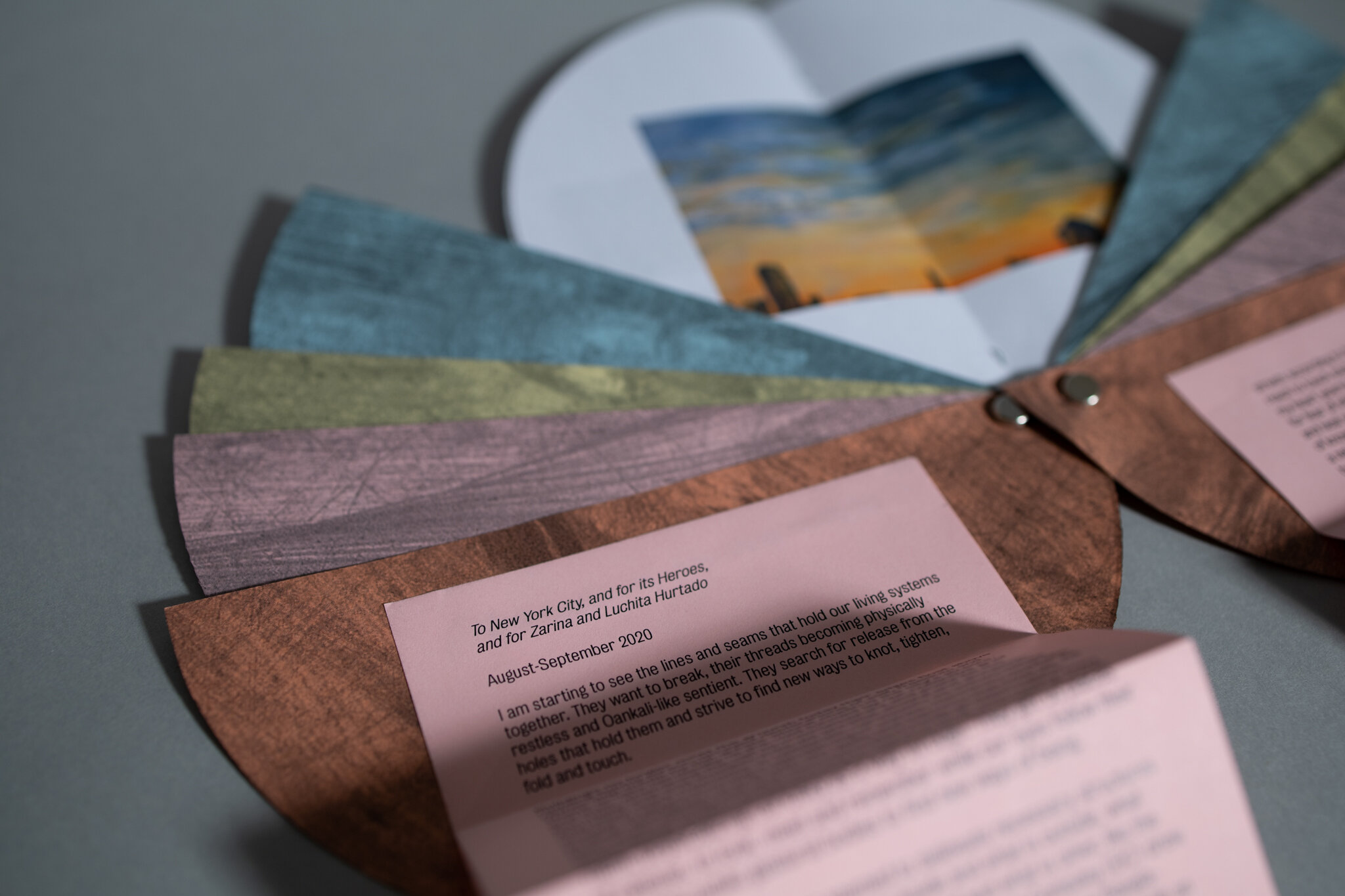

THERE ARE NO EDGES ON THE MOON

7.25” x 3.75”

Martha's Quarterly, Issue 17, Fall 2020, There Are No Edges On The Moon

About the contributors:

Amateur Astronomers Society of Voorhees (AASV), established by Emmy Catedral in 2012, examines the ways in which humans fail to use language to codify what we know about the universe. AASV hosts salons inviting guest artists, historians, scientists, collectors, and storytellers to present or demonstrate on a particular subject or question.

Altynay Demeubayeva received her masters degree at the International Space University and currently works on engineering management and business development at HyImpulse Technologies GmbH, a company located in Germany that aims to provide launch services for smallsats.

Meena Hasan is an artist and educator, born in 1987 and raised in New York City. Her practice uses compositional and material strategies to articulate a South Asian American diasporic experience by investigating subjectivity, self-recognition, translation, pattern, ornament and ritual. Meena maintains her studio in Brooklyn and is currently a Lecturer in Painting at Boston University's School of Visual Arts.

On a clear night, with a full moon, it would seem that the moon has edges. This season, a full moon fell on October 1st; it was a clear night for the mid-autumn festival, a celebration of the harvest that is celebrated in many countries in East and Southeast Asia. This festival usually includes enjoying mooncakes, pastries filled with sweet bean paste and egg yolks and molded into shapes of flowers, dragons, and other prosperous symbols. For children, it is especially memorable because they are often gifted with paper lanterns, usually in the shapes of animals.

Mid-Autumn festival lights in Hong Kong. Image credit: SCMP

On October 1st, my husband and I happened to be driving our newborn daughter from Chinatown, NYC to our home Uptown. We had some mooncakes, and when I looked up at the moon, we were passing the United Nations Headquarters. The complex was so dark that the moon was unusually bright. It is the UN’s 70th anniversary this year, and its celebrations have taken place over the internet due to the pandemic. 70 years ago, this united union among counties was formed to maintain international peace—a new order—after World War II. Today, it’s dark, and the world order is being contested. As the West continues to burn, a new harvest is not certain.

—————

Since the start of the global pandemic, I have taken the opportunity to draw from life more consistently in my visual art practice. This is something that I constantly encourage of my students, but have difficulty upkeeping myself. Drawing from life is difficult; it’s like building muscle through repetitive movements between the eye and hand until that relationship becomes stronger and fluid, sometimes to an instinctual degree. Stop ‘working out’ and that relationship becomes stiff and weak. For me, the challenge in observational drawing is deciding where edges should be drawn, because you are taking something from our dimensional reality and flattening it onto a plane that aims to suggest our lived spaces. Where, for example, does one’s nose start to become their cheek?

I have started to regard observational drawing as an exercise in ethics. So much of looking has humbled me, because it has allowed me to see things that I didn’t know were there, contesting the arrogance of my imagination. Drawing itself can have ethical implications, from where an architect decides to put a doorway to where a government decides to draw a boundary. In these examples and beyond, observation can be a process where those meaningful decisions are informed by a more knowledgeable decider.

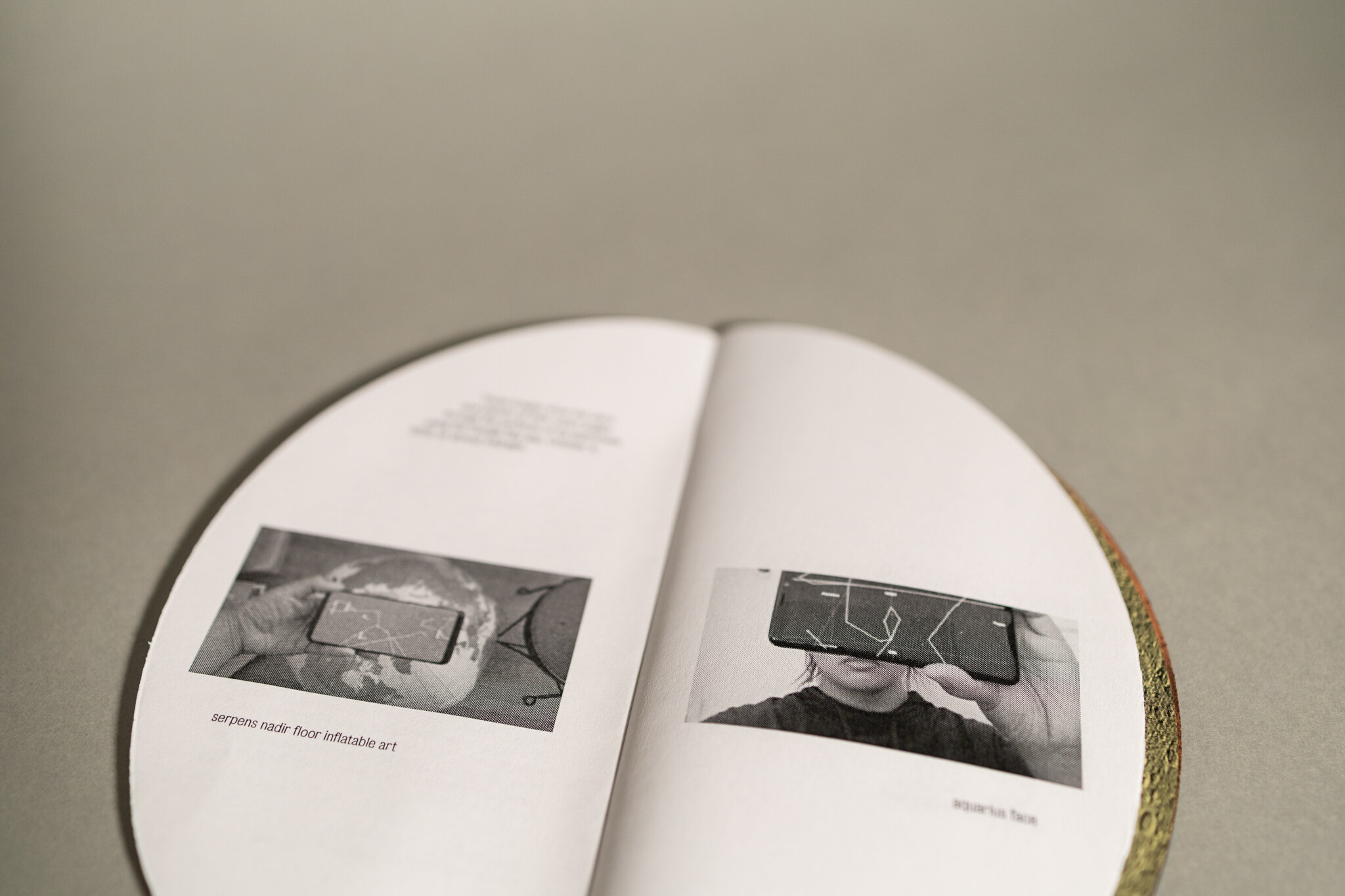

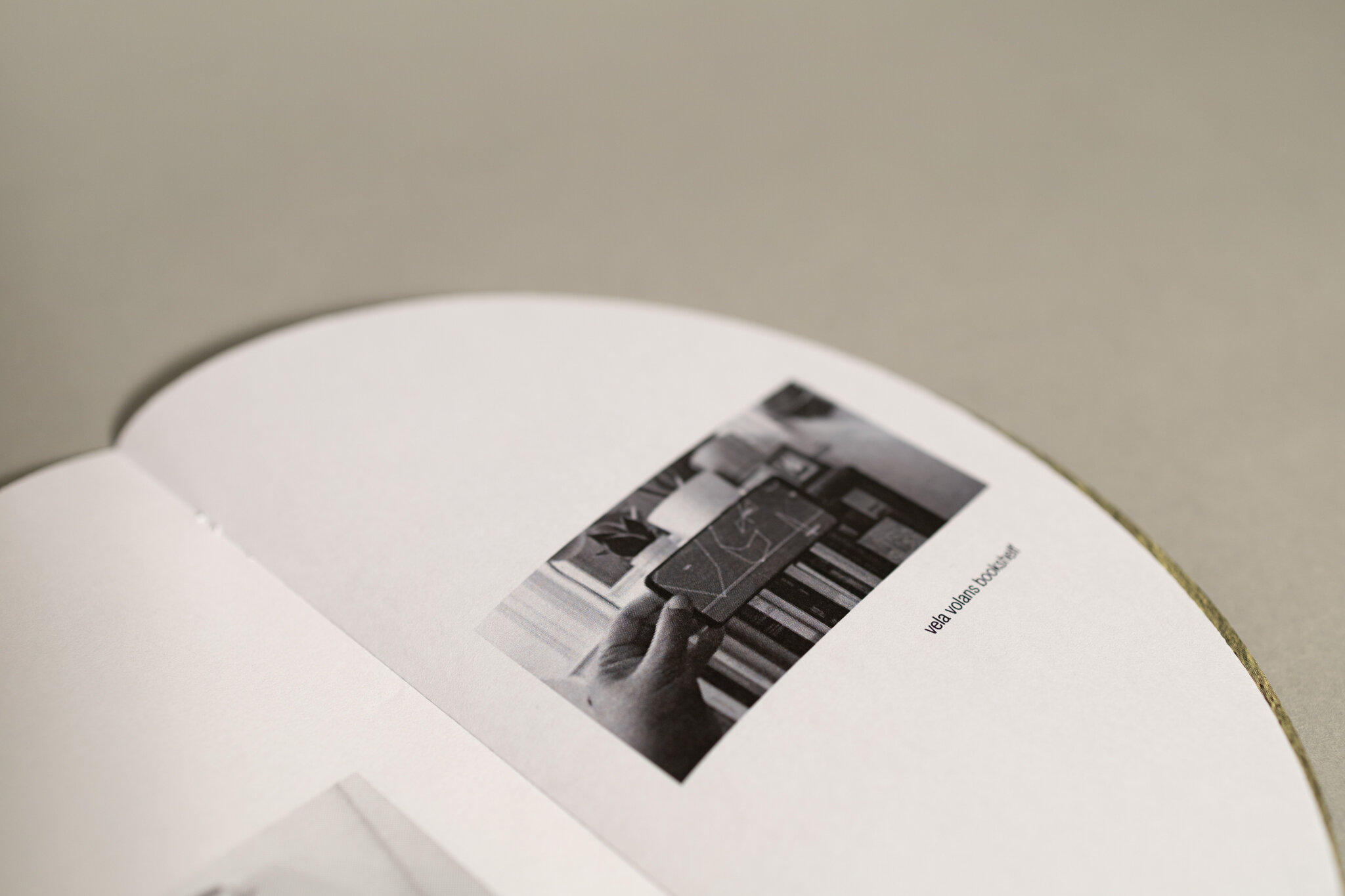

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 17, Fall 2020, There Are No Edges on the Moon, begins with the retelling of a “wrong” drawing. Artist Emmy Catedral’s writing introduces us to the painted ceiling at Grand Central Terminal which, after the great mural of the sky’s constellations was revealed, was proclaimed as an accurate depiction of the stars. It was later pointed out that the drawing of the stars was wrong. Catedral’s writing probes whether “right” and “wrong” is the issue, suggesting rather an issue of perspective. Her writing is followed by a series of photographs that shows her using Google Sky to identify the stars and planets that lie directly on the other side of her home—as if you were to draw a line from her home to outer space. These new constellations do not follow the Western identification system of stars; rather, the system is of Catedral’s own drawing.

The systems drawn by our elite and governing class are going through a reckoning across our planet. People everywhere are living with uncertainty about their health and finances and see that the systems they relied on are actually fragile and vulnerable. The next section of this issue takes us to the artist Meena Hasan, who, like me, has been working from observation since the pandemic. Her writing cites examples where systems and their edges seem so arbitrary yet are so consequential, such as the boundaries drawn between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh today. Related to Catedral’s piece, Hasan’s writing also points out that naming—or identification—creates systems and lines, from the names the US president calls people to the signage on our city streets. But, while describing these drawn systems, Hasan points out that these names don’t carry the same implications amidst the pandemic. After you read her writing, the pamphlet splays out close-ups of Hasan’s paintings and reveals a painting of New York City made from observation from her Brooklyn studio, a painting where the city’s definitive skyline plays a secondary role to the dominant and edgeless sky.

—————

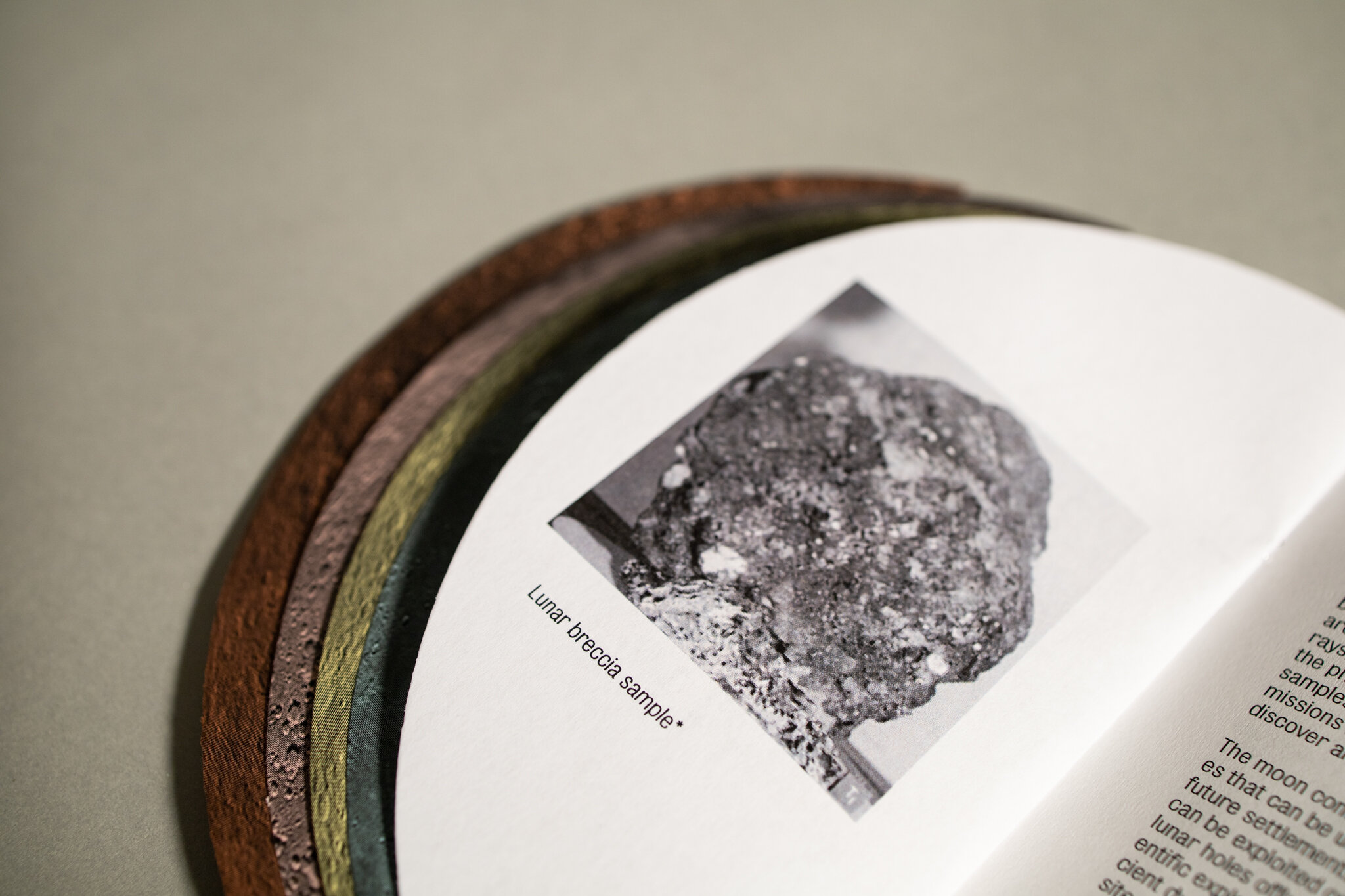

What would it be like to live on the moon?

The next section of this issue describes the technicalities of that foreseeable reality with a piece from space researcher Altynay Demeubayeva, who shares with us some aspects of in-situ resource utilization, the practice of generating products on the moon using lunar materials to support life. Her writing describes some of the geology that possess immense potential to support water and energy.

Artist rendering of the Artemis Lander Development, NASA’s lunar exploration program with aims to create commercial travel to the moon. Image credit: NASA

The reality of visiting the moon became more imminent throughout this pandemic, racial reckoning, and climate crisis, as SpaceX and NASA were recently able to launch their first commercial rocket into space with the expectation that it will take visitors to the moon one day in the near future. There are no edges on the moon yet, but what is evident in Demeubayeva’s writing is that there are close observations being made so that edges—or systems—can be created to support human activity. But who will draw these lines? Who will they be drawn for? Who will they protect? Who will they harm?

This is where the practice of observation has another layer of ethics. After one studies a subject and begins the process of laying down edges, how will they jury the people and environments that they separate and affect? How can edgemakers tamper their power with the humility of deep observation, the humility that comes when your subject is so dense with nuance?

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 16

Summer 2020

12 bpm

5.5” x 4.75”

About the contributors:

Aerica Shimizu Banks is a creative connector, bringing concepts and people together across industries and issues. After careers in tech and environmental policy, she has started her own consultancy, Shiso LLC, and is learning to play guitar.

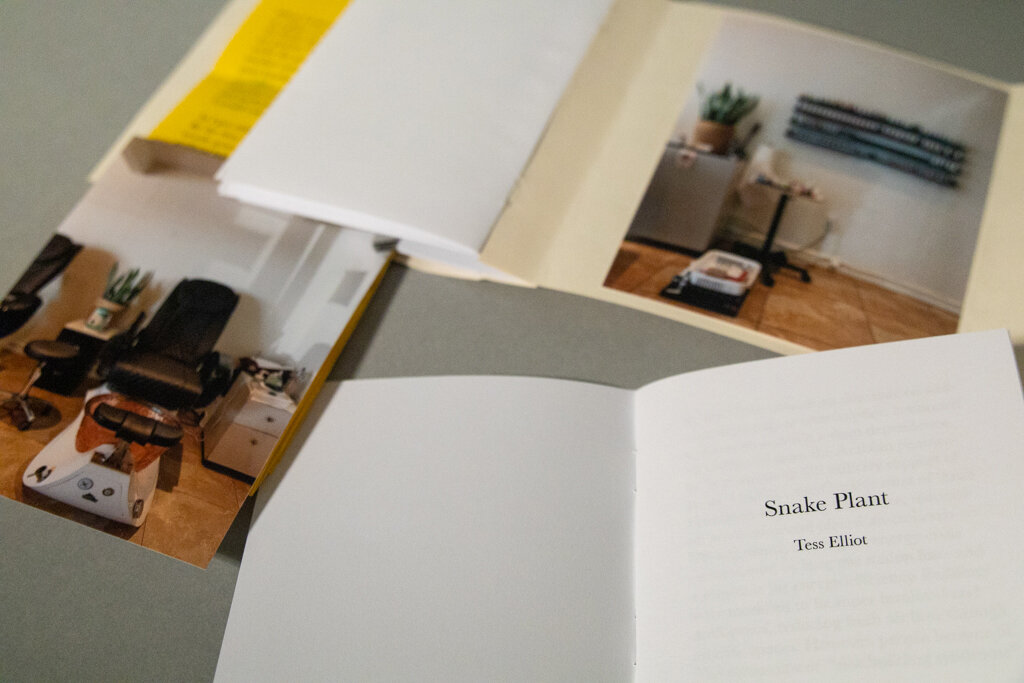

Tess Elliot is an artist working in emerging tech, installation, and film. She is Assistant Professor of Art, Technology, & Culture at the University of Oklahoma with recent exhibitions at Oklahoma Contemporary, Aggregate Space Gallery, and the Ann Arbor Film Festival.

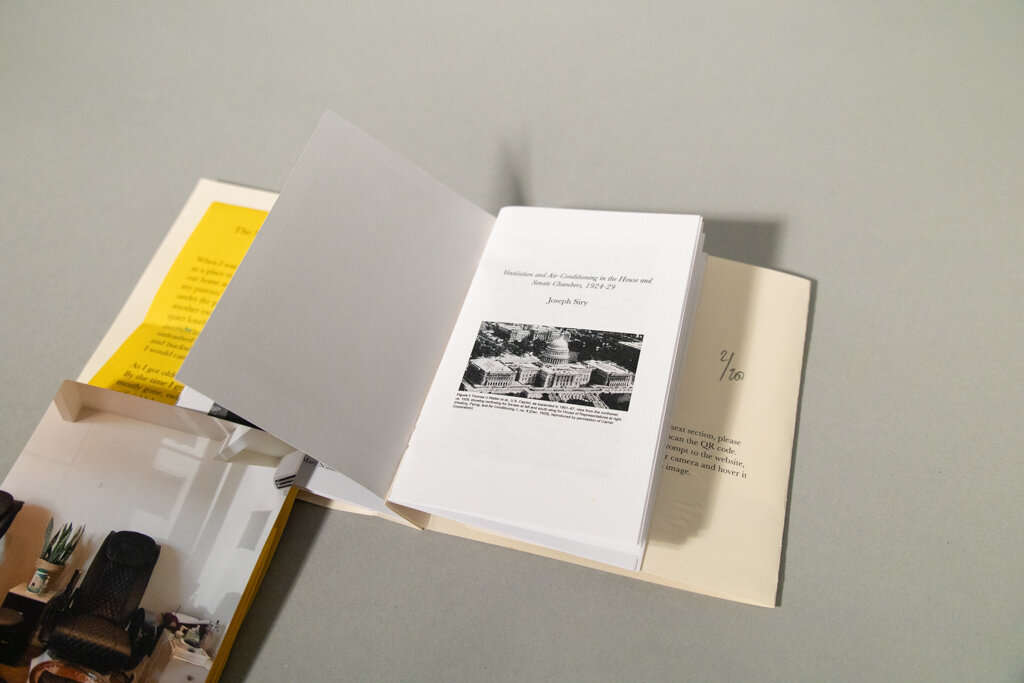

Joseph Siry is an historian of modern American architecture whose concern for climate change led him to his current work on the history of air-conditioning as energy-consuming mechanical systems.

It is murderously hot in New York City this late July 2020. I can feel the heat wanting to muscle through my window as I look out and watch my neighbor bring his groceries into the building from his car. The leafy greens poking out of his Whole Foods bag are wilting in the heat, the metal of his car hot enough to fry eggs, and the polyester of his car seat looks like it could burst into a wildfire. I am inside, breathing in an ice cold room because my air conditioner has been on blast for weeks. My mother had called to caution that these machines could transmit coronavirus. I had impatiently responded to her, “But how are you supposed to breathe without it?!”

We all breathe air, but so often what floats in the air that enters our bodies and gives us life has never been truly considered until now, when the world has been living through the COVID-19 pandemic, a virus transmitted through water droplets that travel through the air. In the last five months, this crisis has illuminated that, among many things, air does not flow equally across racial and class lines, and that the breathing conditions for those with access gives them an upper hand advantage even if COVID-19 itself does not discriminate. Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 16, Summer 2020, 12 bpm, explores three anecdotes about air that point to how this ubiquitous surrounding substance intersects policy and our personal lives.

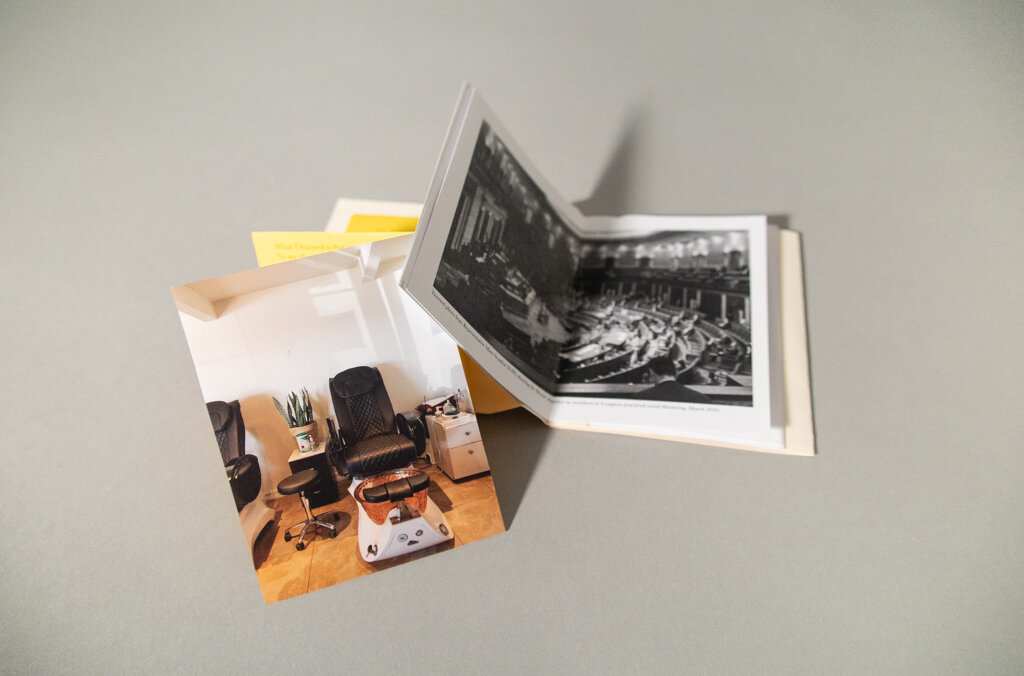

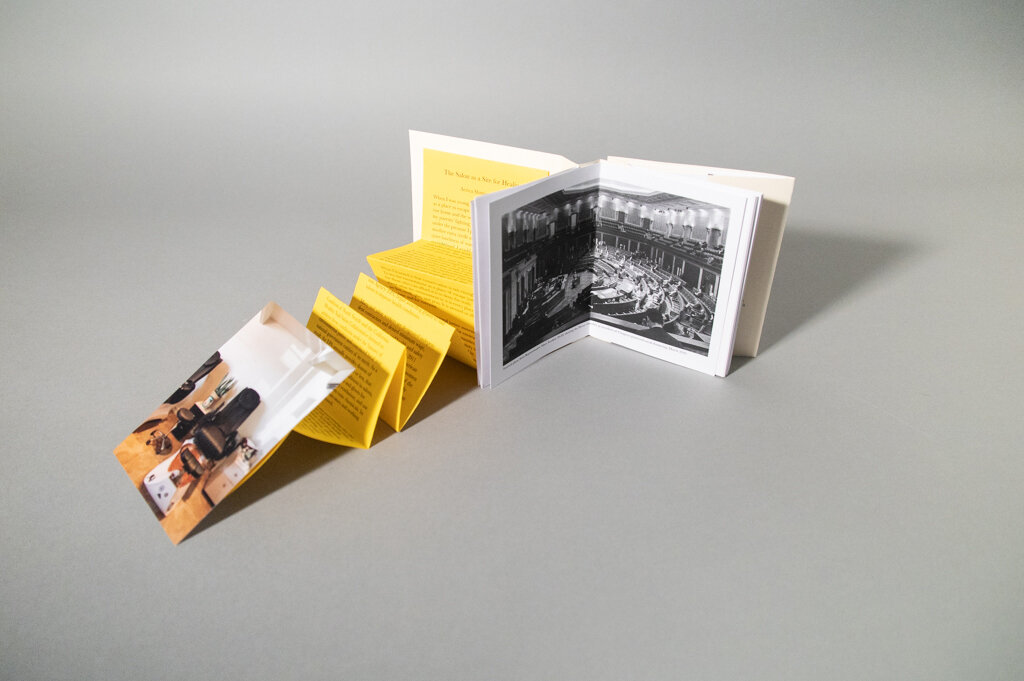

Tweeted photo from Representative Mary Scanlon (D-PA) showing the House Chamber as members of Congress practiced social distancing, March 2020

Amidst this heat wave that is passing through America’s Northeast, America’s entire economy could implode by the end of this week, when millions of Americans lose their $600 supplemental unemployment benefit created under the CARES Act in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Aside from this, the White House continues to encourage the opening of schools and businesses across America, even though there has been a surge of positive cases across the nation’s Sun Belt and in the West. Anxious elderly teachers have written their wills, middle-class parents wonder if they can afford to “pod” with other families, and poor people are left at the mercy of the local and federal governments– not just for options for their children’s schools, but also for options to continue surviving.

Right now, congress is negotiating terms for a new stimulus bill. A few days ago, the Republicans proposed a 1 trillion dollar bill that included slashing the unemployment benefit by $400, offering jobless individuals a $200 weekly supplement. This comes only a few days before August rent is due and other monthly bills. As I sit here in my confusion at the cruelty of what this GOP proposal entails, I wonder what air such powerful people are breathing? What air causes them to separate their humanity from their countrymen? What air makes them deny that what they breathe is also what we breathe?

Beautiful Nails in Laguna Beach, CA. Photo by Patrick Ngo

12 bpm stands for 12 breaths per minute. Any human who breathes below 12 breaths per minute will need medical relief. This could mean that the person cannot breathe on their own and will need the assistance of a ventilator; it could also mean that the person needs their inhaler. Or it could mean that the person needs to come inside, where it is cooler, for a glass of water. The House and Senate chambers, where decisions are being made today about our lives, were transformed into a different kind of ventilated space in 1929, when the capital’s buildings were installed with the first air conditioning system. This issue of Martha’s Quarterly features an excerpt from the historian Joseph Siry’s article Air-Conditioning Comes to the Nation’s Capital 1929-60, which first appeared in the December 2018 issue of Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. In it he details the conditions by which this important transformation brought a new environment for government. The decision to change the air circulation system in the Senate and House was a discussion that came soon after the the 1918 influenza epidemic, when the dry heated air was blamed for the spread of the flu, and the excessive heat of the summer depleted the energy and tested the tempers of all those who worked in these consequential chambers. It was believed that fresh air would allow for better life and energy for the people inside the buildings. Implicit in this massive, yet subtle, architectural change is that the government would be better functioning if it could breathe more easily.

As I continue to write this, I am grateful that I am able to form sentences in a space where I am privileged with cool clean air to let me work during the midst of this torrid New York summer. The news is on in the background and hums like the sound of my air conditioning machine. Lately, Governor Cuomo has brought up the issue of ventilation systems in his briefings. As we have lived with the lingering coronavirus, we have learned that droplets can circulate and rotate in our indoor air circulation systems, allowing more opportunities for the virus to infect individuals who are inside spaces for prolonged periods of time. As businesses and institutions try to reopen, air ventilations systems need to be considered carefully, and oftentimes– as in the case of public schools or small businesses– there simply is not enough money or support to accommodate a safe indoor space, air circulation being only one of many markers for a safe space.

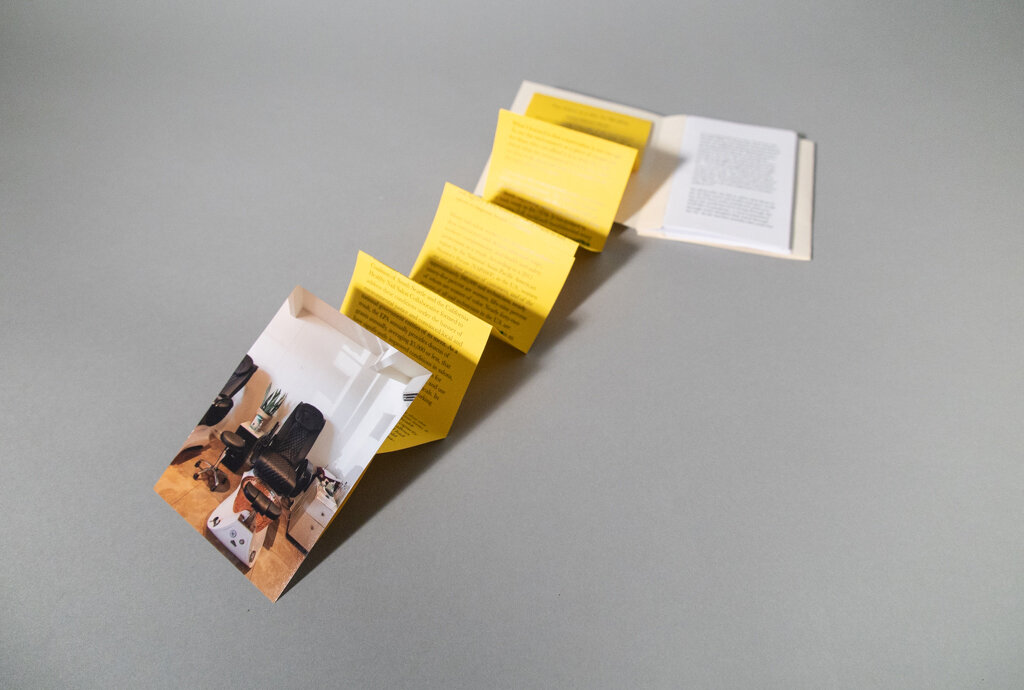

When you open the left cover picture of a nail salon of this issue, you will also unravel the air condition unit pictured on the front cover. The strip of yellow paper features a piece by policy lawyer Aerica Shimizu Banks, who pens an illustration of how a community’s environment is a reflection of the policies that shape it. More urgently, Banks explains how one’s environment is also a consequence of racial and colonial legacies webbed on our laws. In other words, the air that we breathe, while invisible, reflects the systemic structures that have oppressed, uplifted, and maintained certain groups. This is clear in Banks’ description of nail salon workers, who are exposed to harsh chemicals daily, and the relief that they need to provide them with a healthier air circulation system.

Beautiful Nails in Laguna Beach, CA. Photo by Patrick Ngo

Nail salons were not deemed essential businesses, and many of the industry’s workers have suffered throughout the pandemic’s business closures. These workers– many of whom are low-wage earning women of color– along with many other working-class Americans live amidst constant health risks and economic anxiety. This stress is also occurring as the nation is enduring a racial reckoning ignited by the heinous murder of George Floyd, who cried under the knee of Officer Derek Chauvin, “I can’t breathe!” Since May, protests gathering people of all ages, races, and locales have taken to the streets, despite the looming threat of the coronavirus. Chants cry, “Defund the Police!” and “No Justice, No Peace!” Throughout June, looters raided boarded up stores, police cars were torched, and fantastic fireworks lit up the skies across America. The most recent escalation has been the visible force inflicted by Federal Agents on peaceful protesters in Portland, Oregon.

And it is still so scorching hot outside. “How is everyone breathing? Where do they go home to rest?” are some questions I constantly ask.

And so, this brings us to the last contribution in this Martha’s Quarterly. Artist Tess Elliot created a virtual reality experience wherein a snake plant appears on your phone when you hover it over the image of the nail polish bottle. This artwork extends from her writing about the political significance of this domestic and common household plant. In her writing, Elliot describes a time in the 70s when there was an energy crisis due to a lack of oil; as a result, buildings were insulated and designed to be draft-proof, causing a lack of airflow. As a result, people became sick, reporting symptoms of itchy eyes, rashes, congestion, and more. In response, NASA published Interior Landscape Plants for Indoor Air Pollution Abatement in 1989, a report that encouraged the addition of plants, particularly the snake plant, in closed spaces because of their air-purifying qualities. This was published with the simultaneous desire to create more air purified spaces in space stations and future extraterrestrial colonies.

Throughout the coronavirus lockdown, houseplants have been a source of solace for many people. On social media, pictures of social strife have been interrupted with pictures of newly potted plants– many of them snake plants– that offer a little bit of peace and happiness in a time of prolonged uncertainty. I recall a few pictures of plants that I saw from a friend who is healing from Covid-19. He said he is not back to normal, that he has to take each day slowly, that the virus has changed his breathing, that he cannot breathe as easily anymore. But the plants seem to offer something: if not solace, then something else that remedies the toxic air that seems to have penetrated all layers of our social fabric. I think about the plants that could be waiting at home, purifying the air of all those who are sick, those who are waiting for Congress to make a decision from their air conditioned spaces, or those who have spent a day protesting for social justice– or, more broadly, air for all of us to breathe equally.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Martha's Quarterly

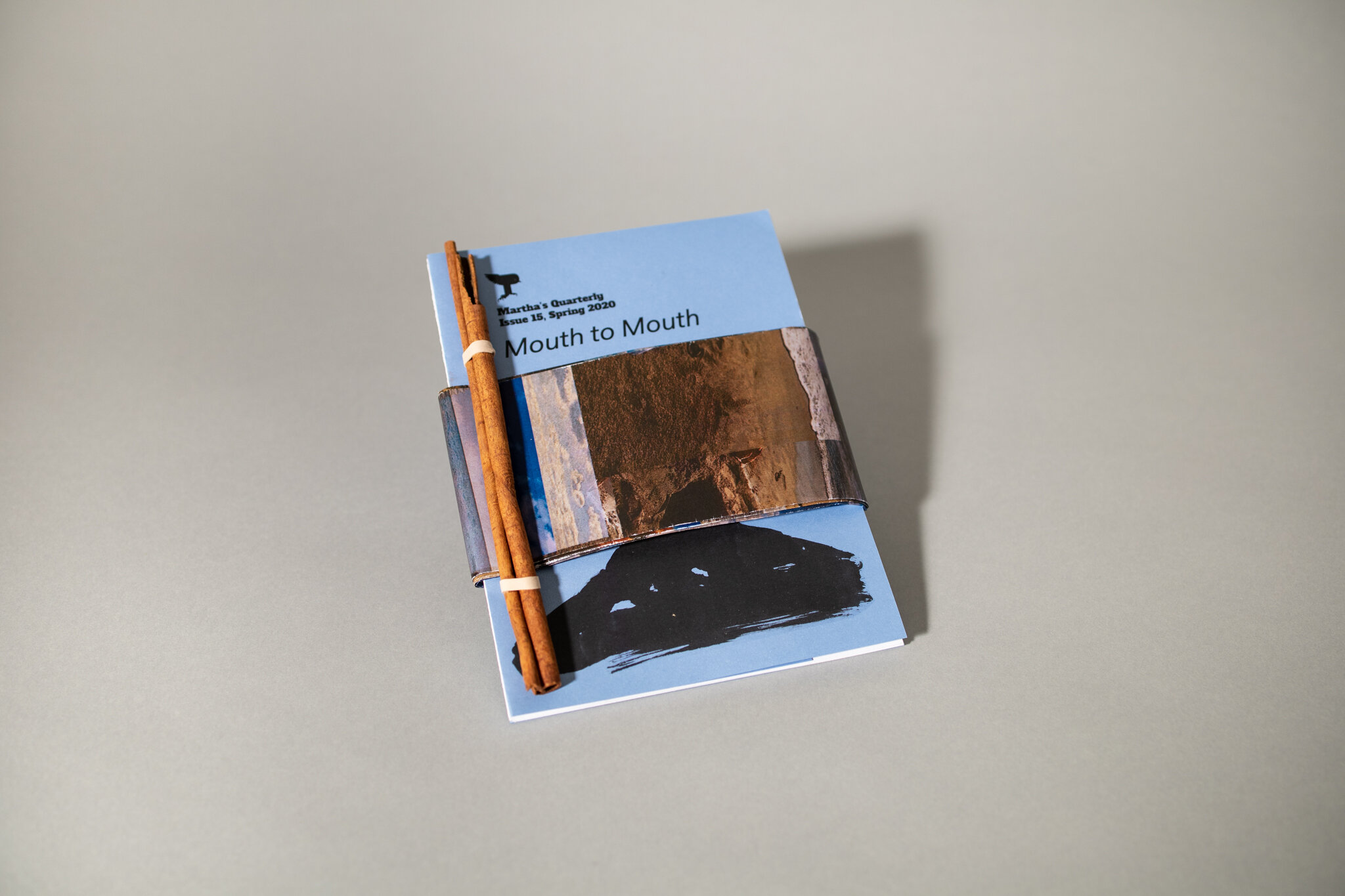

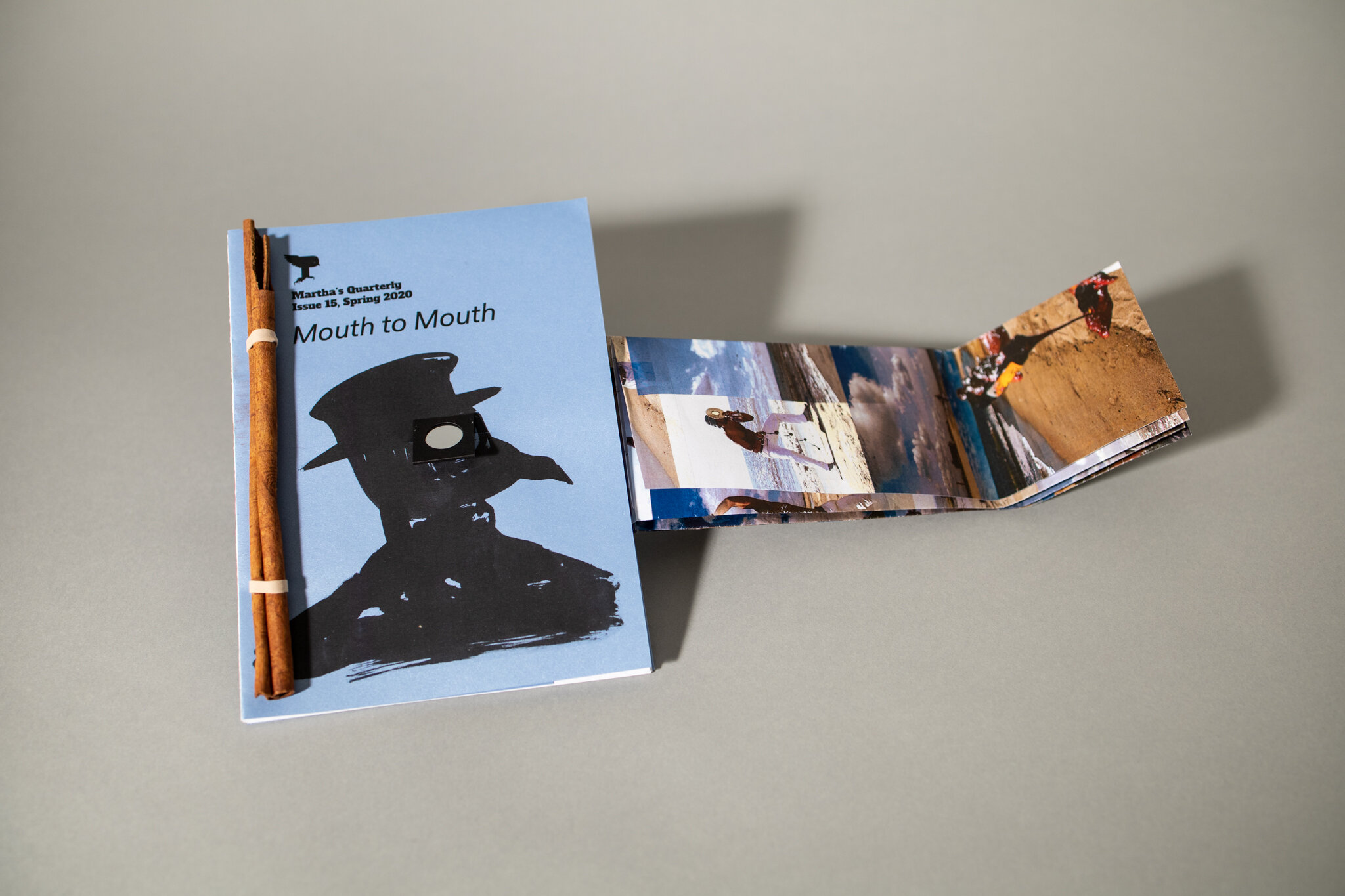

Issue 15

Spring 2020

Mouth to Mouth

8.5” x 6.5”

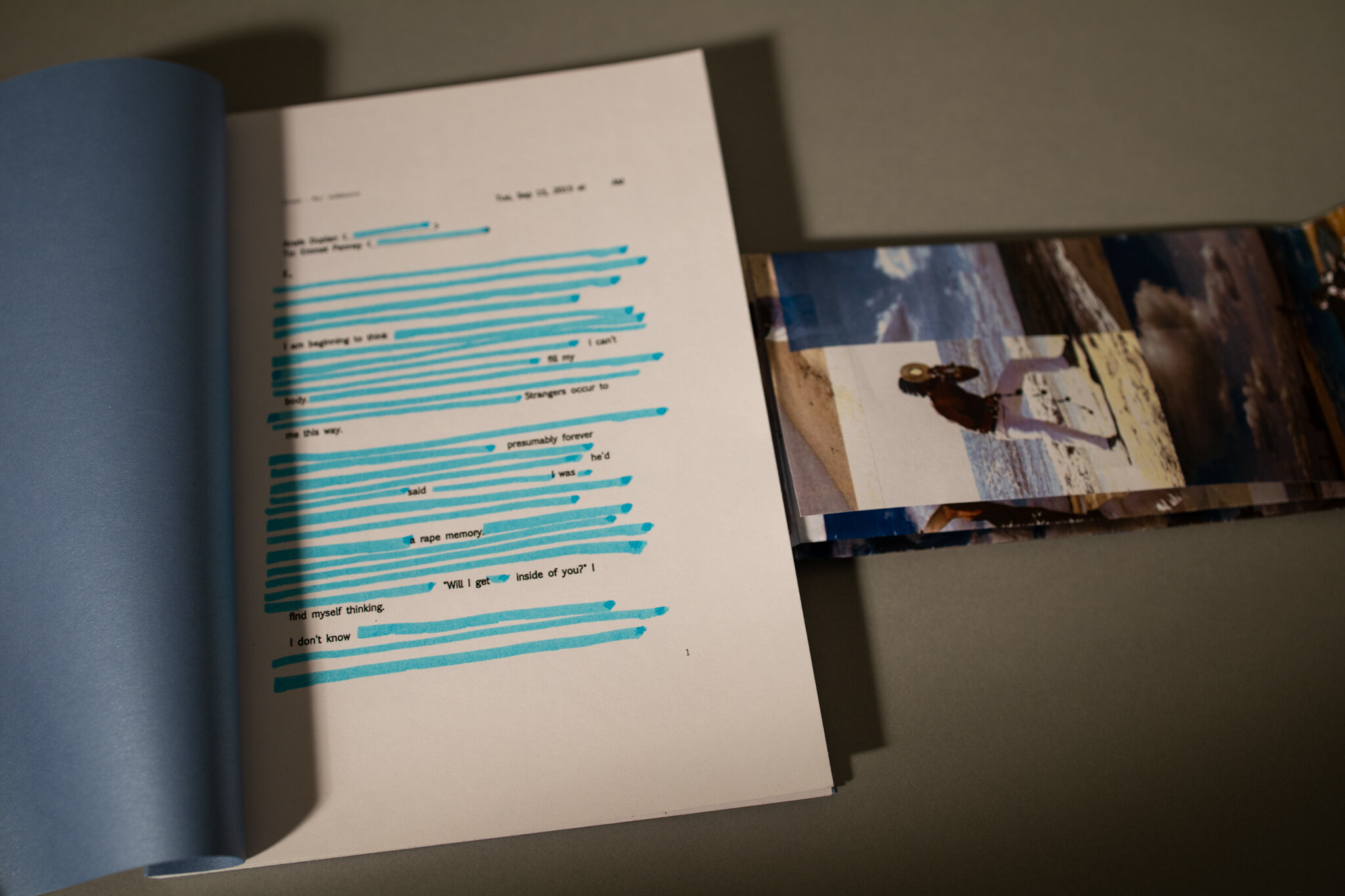

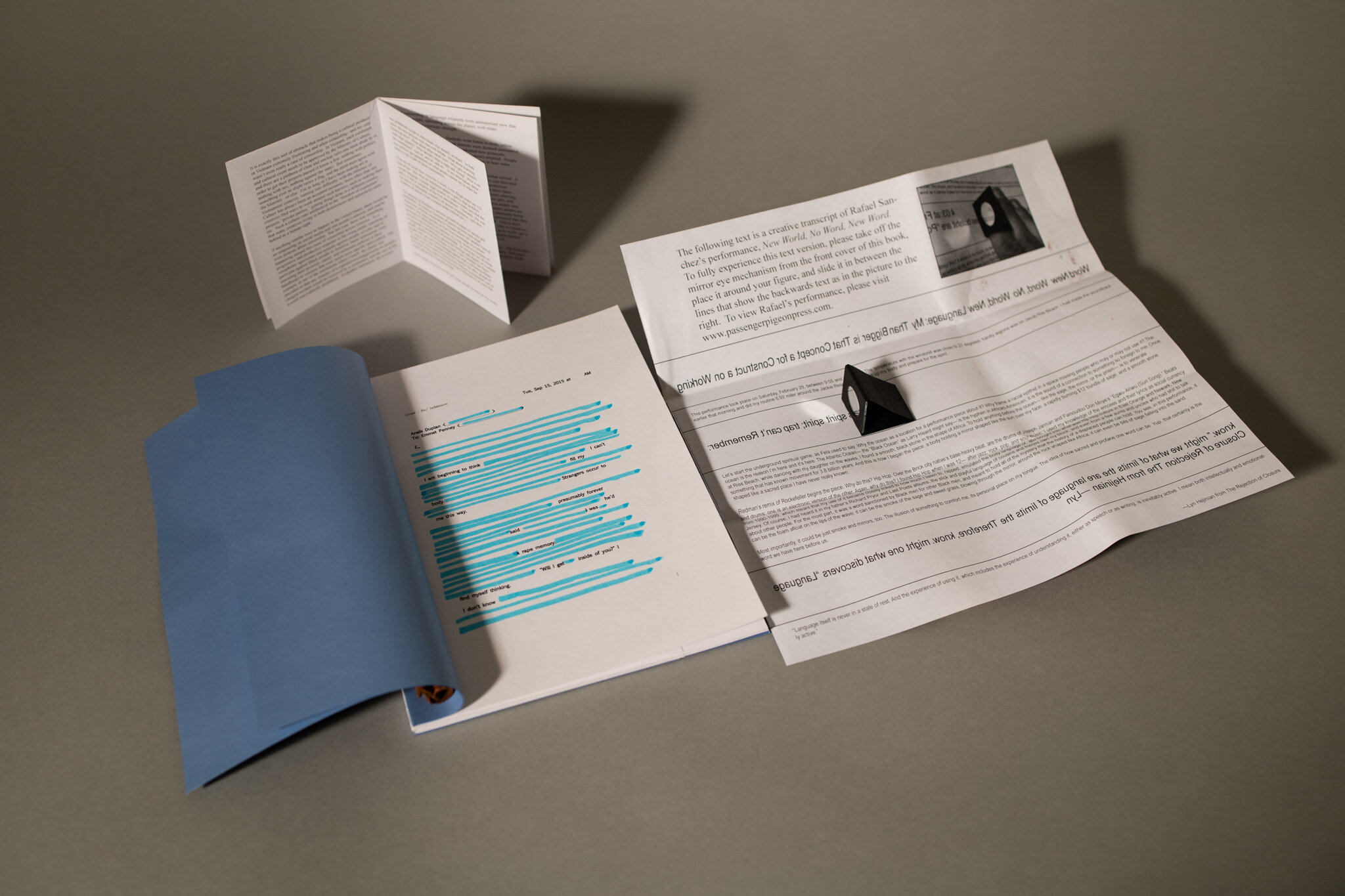

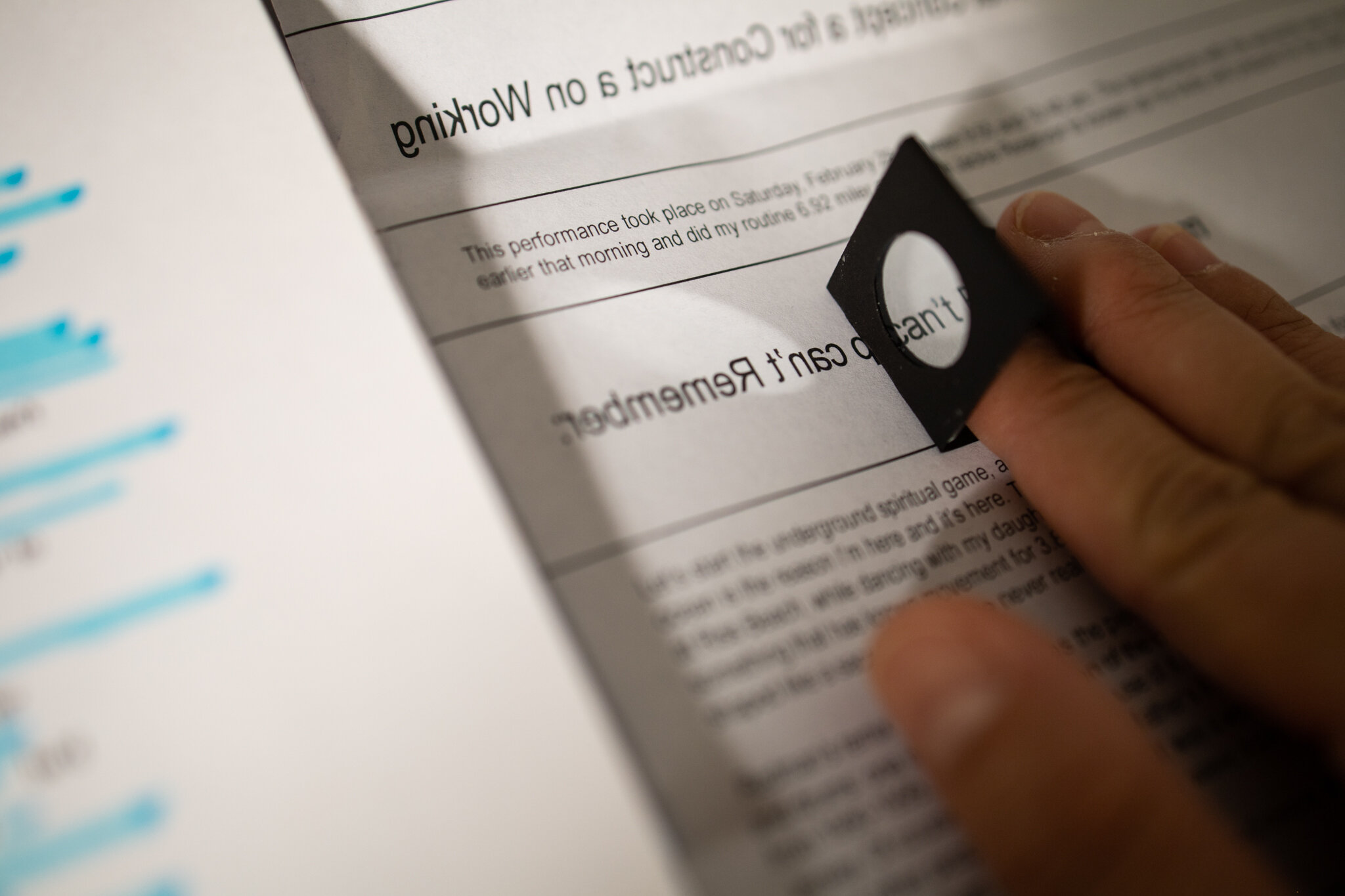

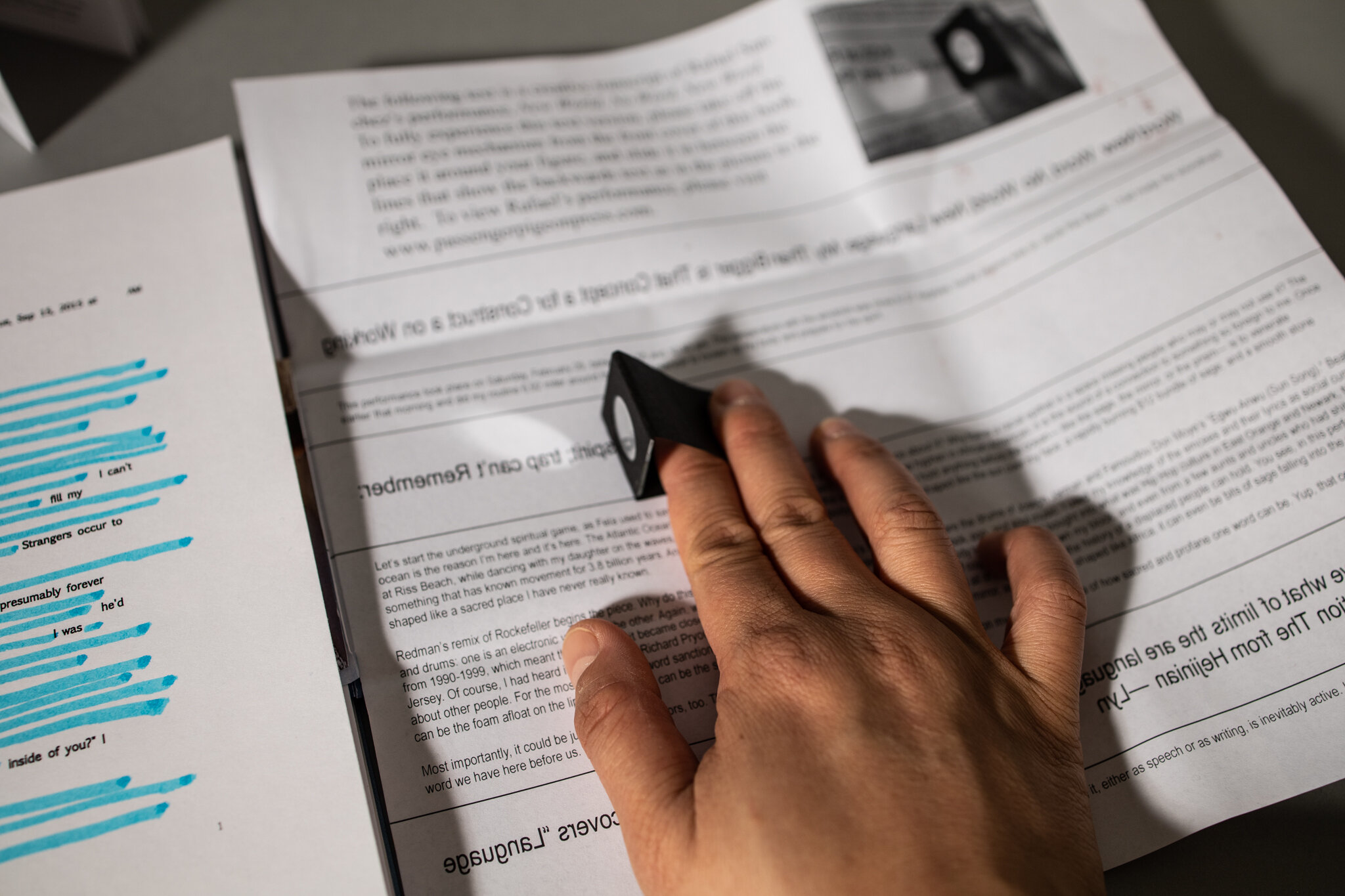

Below is a video of a performance by Rafael Sanchez entitled New Word No Word New World. This was his response to Passenger Pigeon Press’s prompt to “exonerate the n-word.” We took this performance and turned it into a component of this season’s artist book. Between 3.40 - 8.50 the sound is silent due to copyright issues. If you are a current subscriber, we will send you a private and non-distributable copy of the unedited version to accompany your reading experience.

About the contributors:

Anaïs Duplan is the author of Blackspace: On the Poetics of an Afrofuture (Black Ocean, 2020), a forthcoming book of essays on black digital media artists. He is the founding curator of the Center for Afrofuturist Studies and Program Manager at Recess.

Rafael Sanchez, a Newark native and avid lover of cricket sounds and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge's poetry, began his performance art career in 2000, chasing buses through the Central Ward of the Brick City. Since then, he has explored endurance and installation performance, developed a deep admiration for Butoh, Bill T. Jones, and Merce Cunningham, consistently asked his audience to make a psycho-educational commitment to understanding his work. He teaches in Brooklyn and lives in Harlem.

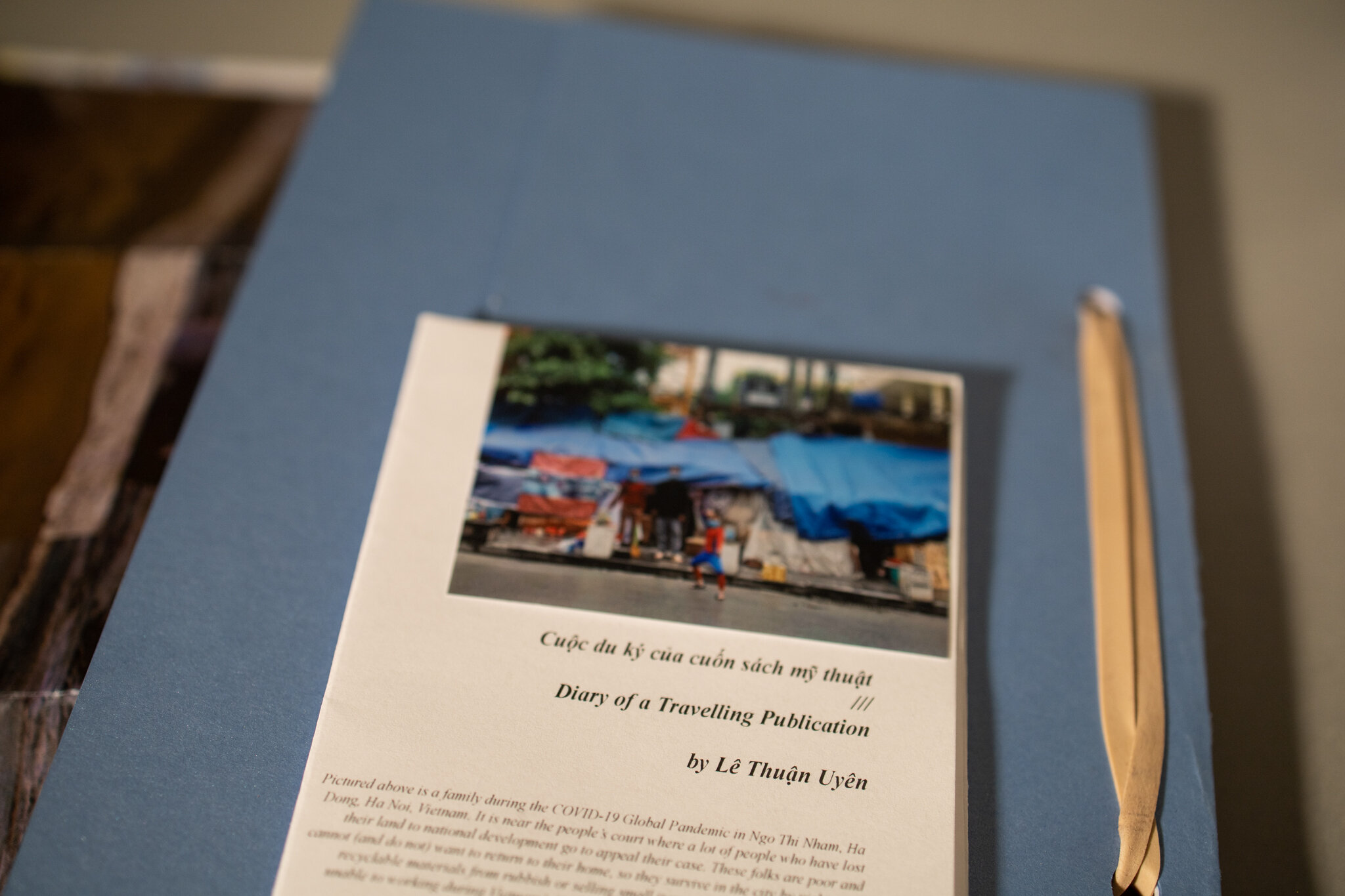

Lê Thuận Uyên is a curator based in Saigon, Vietnam. Beside her dedication to hanging out with artists, Uyen is interested in investigating alternative micro histories of Vietnam that are sidelined or absent from the mainstream narrative.

Today is May 9, 2020. I have been at home under Governor Cuomo’s shelter-in-place order since March 20th, 51 days ago, and have since made a new normal routine of teaching online, making art on my kitchen table, cooking every meal, and taking long walks from my apartment to the flower conservatory in Central Park. Amidst the uncertainty of our public health and economy, I have found joy in looking at the flowers bloom wildly at the conservatory. I never made the time to visit the conservatory before these strange circumstances and was surprised by how much happiness I felt marveling at the abundance of color within the flowers, the strange shapes of their pistils, and the potency of their fragrance. Among these flowers were many different species of daffodils, all named after Narcissus, the beautiful youth of in Greek mythology who fell in love with his own reflection.

Echo And Narcissus, John William Waterhouse

One year ago, I was working on a body of work for an exhibition in Vietnam that expanded on the image of the daffodil to explore ideas about identity, the need to define the “self,” and how this process can lead to one’s demise. My work also also flirted with the idea that colonial projects were endeavors of self-definition for the colonizer, where the quest to conquest came out of a need to fulfill a sense of self. The work turned out to be a body of 12 paintings and some small sculptures; while they were not explicitly political, they were held at customs upon their arrival in Vietnam because the shipper from New York had labeled them “artwork” instead of “gifts.” Anything labeled “artwork” coming into Vietnamese customs receives a high level of scrutiny and often an unnecessary amount of hassle. The exhibition opening was postponed for a week in order to get the artworks out of customs.

It is exactly this sort of obstacle that makes being a cultural producer in Vietnam extremely frustrating and often exhausting-- and my case wasn’t even really a case of censorship. In Vietnam, each exhibition and cultural event needs to be approved by the Ministry of Culture, and there are a plethora of clear and unclear rules one must abide by in order to get their projects passed (I know a few: nothing with politics, nothing with sex, nothing against the state). But sometimes, something ever so slight raises a flag, and the artist must agree with the Ministry– or else. For as long as I have been making art in Vietnamese contexts, running into difficulty with the Ministry of Culture has always been an accepted nuisance; more often than not, creatives find ways to work around such barriers, such as making their projects “private parties,” getting things done in a different country, etc. Such a culture runs antithetical to the “freedom of expression” that many creatives living in both democracies and autocracies unite behind as a human right.

If anything similar were to happen in the United States, there would be an outpouring on social media and into people’s inboxes, and maybe even protests about censorship. But last year, there was something happening around this issue of censorship across America. As a progressive and productive response to the rising public reporting of xenophobic agressions and assaults against people of color and in particular against Black people in America, many institutions were amending their diversity, equity, and inclusions policies in their handbooks to versions that were much more specific and explicit. For example, at one of the institutions where I teach, the clause was amended so that any instance of a reported microaggression or racially charged incident would be reviewed by a committee, and the use of the n-word was explicitly prohibited. At another institution, the n-word was prohibited except to individuals who identify as Black. In both cases, the new policies were met with debate. What about teaching historical texts? What about other racial slurs? Who gets to identify with what identity? Who decides what is right and wrong? Who is on the committees? And on, and on, and on... In my observation, these new policies put parameters on what people cannot say in order for them to stay a part of these communities.

Pro-Trump Protester with a "My body my choice” sign.

(The use of racial slurs, even the n-word, is not illegal under any US federal law. But when an institution adopts a policy that prohibits certain language, it needs legal counsel in order to make sure that the policy is not in violation of the first amendment. Ultimately, the way the policy is ultimately worded is of utmost importance, such that freedom of speech is not violated under federal law.)

The question of freedom is intrinsic to both freedom of speech and censorship. In America, freedom of speech protects individual expression, whereas censorship in Vietnam allows for another kind of freedom: one where people are free from knowledge of a certain spectrum of information or opinions. In a way, there is a freedom to not receiving certains kinds of knowledge. So when the use of words or language is prohibited to protect the feelings and dignity of a certain people, another kind of freedom is born: a new freedom for those people who can now move through spaces with a refreshing liberty. Of course, this new freedom becomes a barrier for other groups of people who were used to uttering slurs without consequence, not so dissimilar from creatives trying to express themselves in ways that would offend the Vietnamese state.

Propaganda poster in Vietnam during Covid-19 Shelter-in-Place, 2020

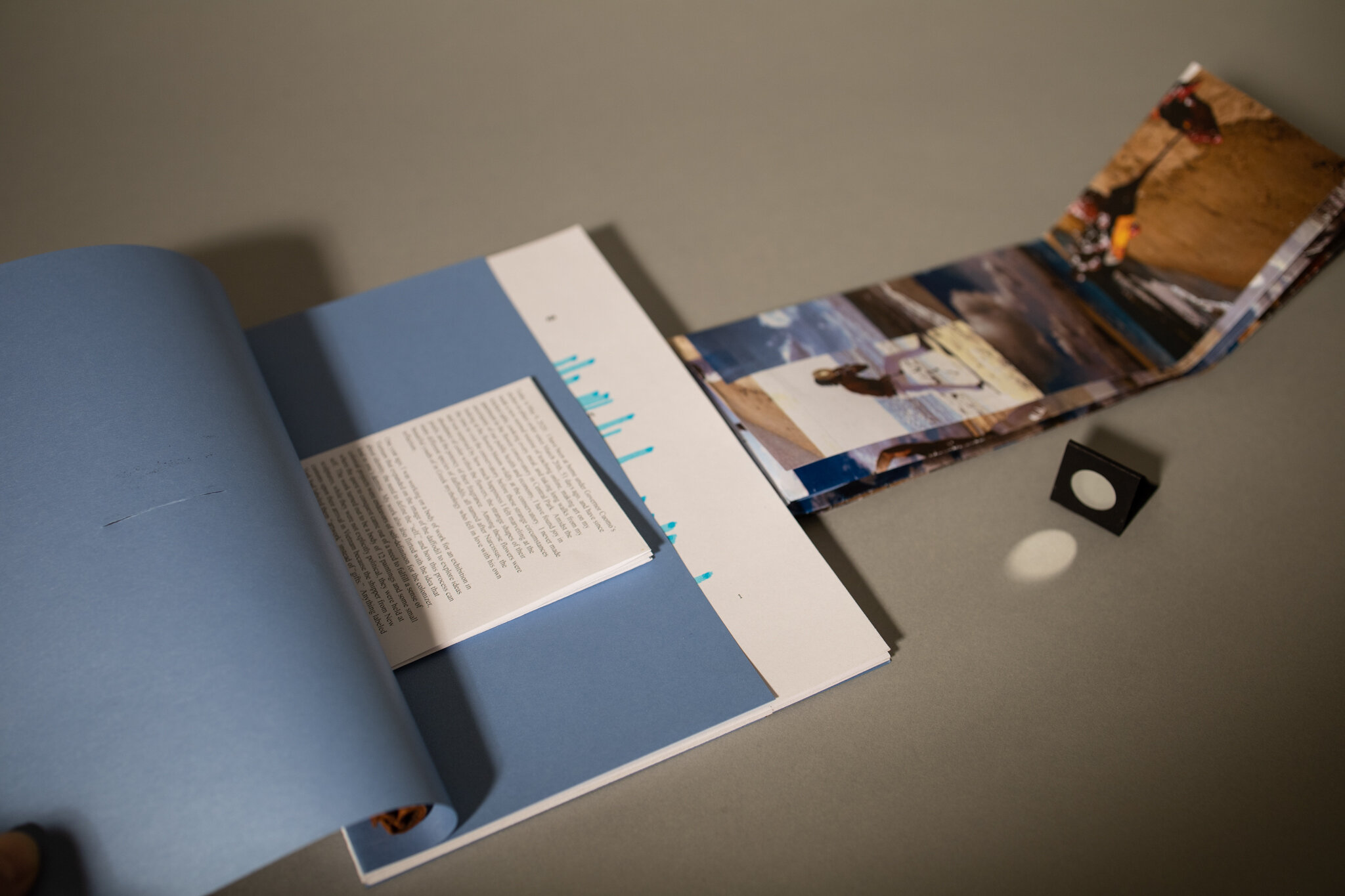

There seems to be no way for any large people to truly be free in the most romantic and liberal understanding of the word, but I wanted to explore these issues around freedom of expression by putting side-by-side the issue of censorship in Vietnam, the significance of banning the n-word in America, and what it means to take out words or not say words in general to create space. In late winter, I asked the Vietnamese curator Lê Thuận Uyên to contribute a piece that speaks to the process of working creatively within a censored context. She offers a humorous and serious account of producing an exhibition catalog that the Ministry of Culture in Vietnam did not approve. At the same time, I invited the performance artist Rafael Sanchez to create a performance that could “exonerate” the n-word. Sanchez and I teach at the same school, so we talked about what its new rules meant to us as individuals. Sanchez, a Black man, talked about how the word has been used throughout his life, from endearing to violent contexts, and how he has chosen to limit the use of the word in his own life. His performance trails a soundtrack of music, all of which uses the n-word in a variety of ways; on a freezing morning at Riis Beach, Sanchez created a ritual to this soundtrack where he lit sage, covered himself in molasses, cinnamon, and flour, and ultimately buried himself into a sand pit while reflecting a mirror into the sun. Finally, I invited the poet Anaïs Duplan to contribute one of his erasure poems, where he takes emails and deletes words to make the remaining words form new meaning into poetry. His heartfelt craft exists outside of the politics of the n-word and Vietnamese censorship, as in the former examples; however, it exemplifies how amorphous words can be, and the simple yet mighty power in such an ability to erase.

And then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and it seemed that whatever trajectory this Martha’s Quarterly wanted to pursue needed some recourse. At first it seemed to me that whatever questions I wanted to ask about censorship or language etiquette were unimportant now that a disease was wildly spreading across the planet, with many succumbing to its mysterious strength.

The world quickly shut down. Students went home to study online with their teachers. Eye doctors and dentists were deemed unessential, so they went home too. Grocery stores adopted new protocols, allowing only a few shoppers at a time. The streets emptied. People stayed inside anxiously watching the news, waiting to hear some report of certainty.

John Oliver's 'Last Week Tonight' episode on coronavirus featuring Wash Your Hands, a viral Tik Tok video from Vietnam

In the first few weeks, living in New York was somewhat surreal. A city that is always bustling was eerily quiet; the news was drowned with reports of people dying and a lack of personal protective equipment and ventilators; the images of nurses with their faces bruised from wearing masks for 12 hour plus shifts were sobering. Meanwhile, more and more people started to lose their jobs, and anxiety over bills started to sound the alarms. It is now nearly two months since the economy stopped in America, and many people are demanding that the economy open again, despite the imminent threat of a second wave of COVID-19. Some people have protested that they do not want to wear a mask to prevent droplet spread. This is their freedom, they all cry. Their freedom is being stolen. This is America, where they should be able to do whatever they want: go to work, get a haircut, not wear a mask. “My body, my choice!” a protest banner read. So far, 80,562 Americans have died of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, in Vietnam, no one has died of COVID-19. The first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 23rd. Since then, 268 cases have been reported. Vietnam has a population of 95 million, more than South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore combined, and yet it has had arguably the most successful response to this virus. Much of its success comes from the simple but strict means of testing and contact tracing: anyone who was infected and all their immediate contacts were immediately quarantined. On top of this, there was a unified national rallying to fight the virus. Two mobile apps were quickly developed that allowed people to record their health; lively, creative media campaigns informing the public about COVID-19 that flooded the streets with posters, social media, and TV cartoons. One song about washing your hands was so catchy it ended up on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. Today, Vietnam is open, and I see my friends there enjoying restaurants with each other again, each with a unified awareness and precaution that the virus still lingers. Vietnam is free.

Paul Fürst, engraving, c. 1721, of a plague doctor of Marseilles

This new backdrop of freedom to live with or in ignorance of COVID-19 is our new normal, which is how I’d like to contextualize the issues of freedom to express that the contributions of Lê Thuận Uyên, Rafael Sanchez, and Anaïs Duplan bring forth. Freedom of speech and the right to life are interconnected. What we say as individuals affect the wellbeing of others, and what institutions, such as schools, companies, and nations say, can protect or endanger their communities.

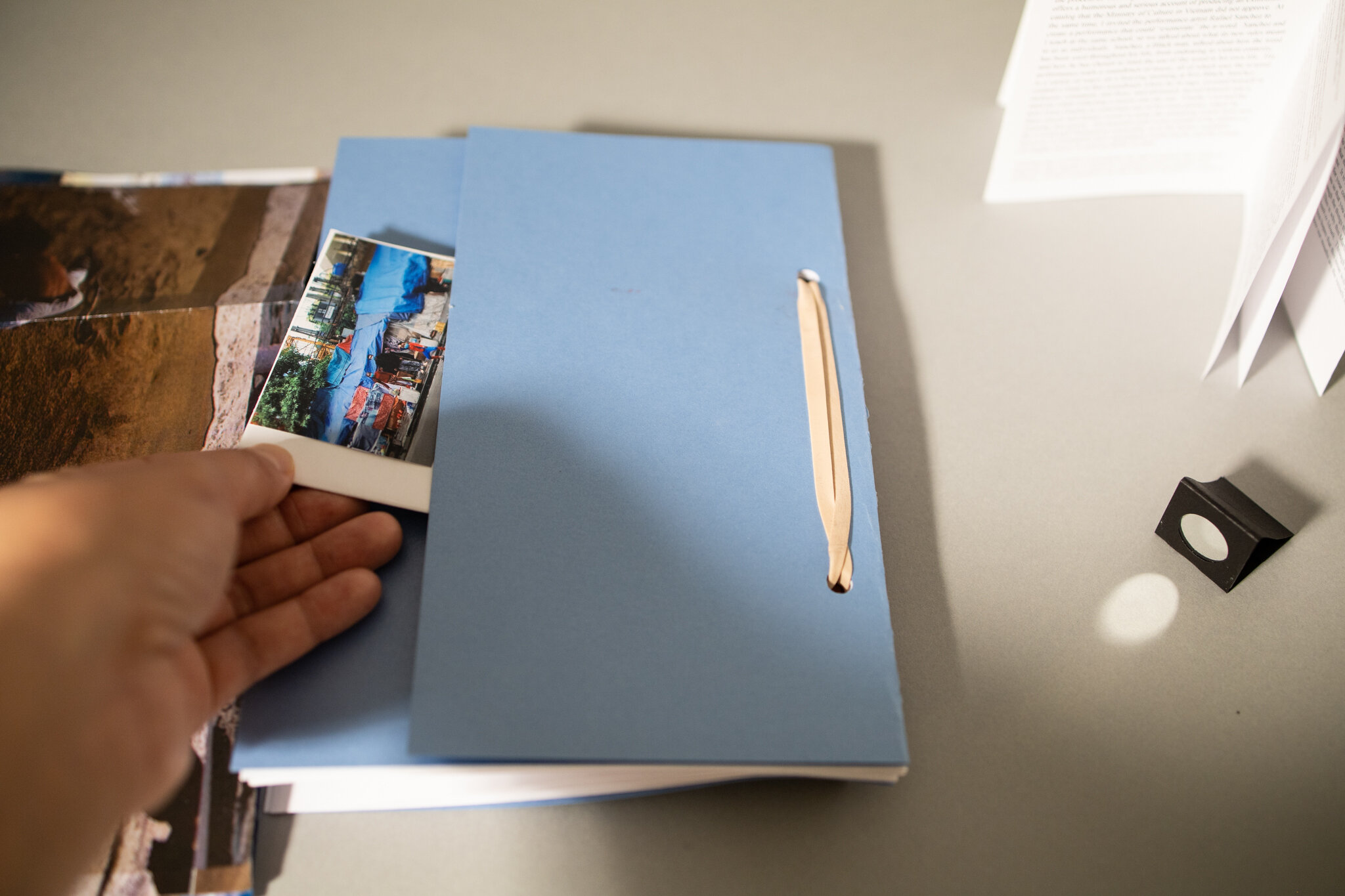

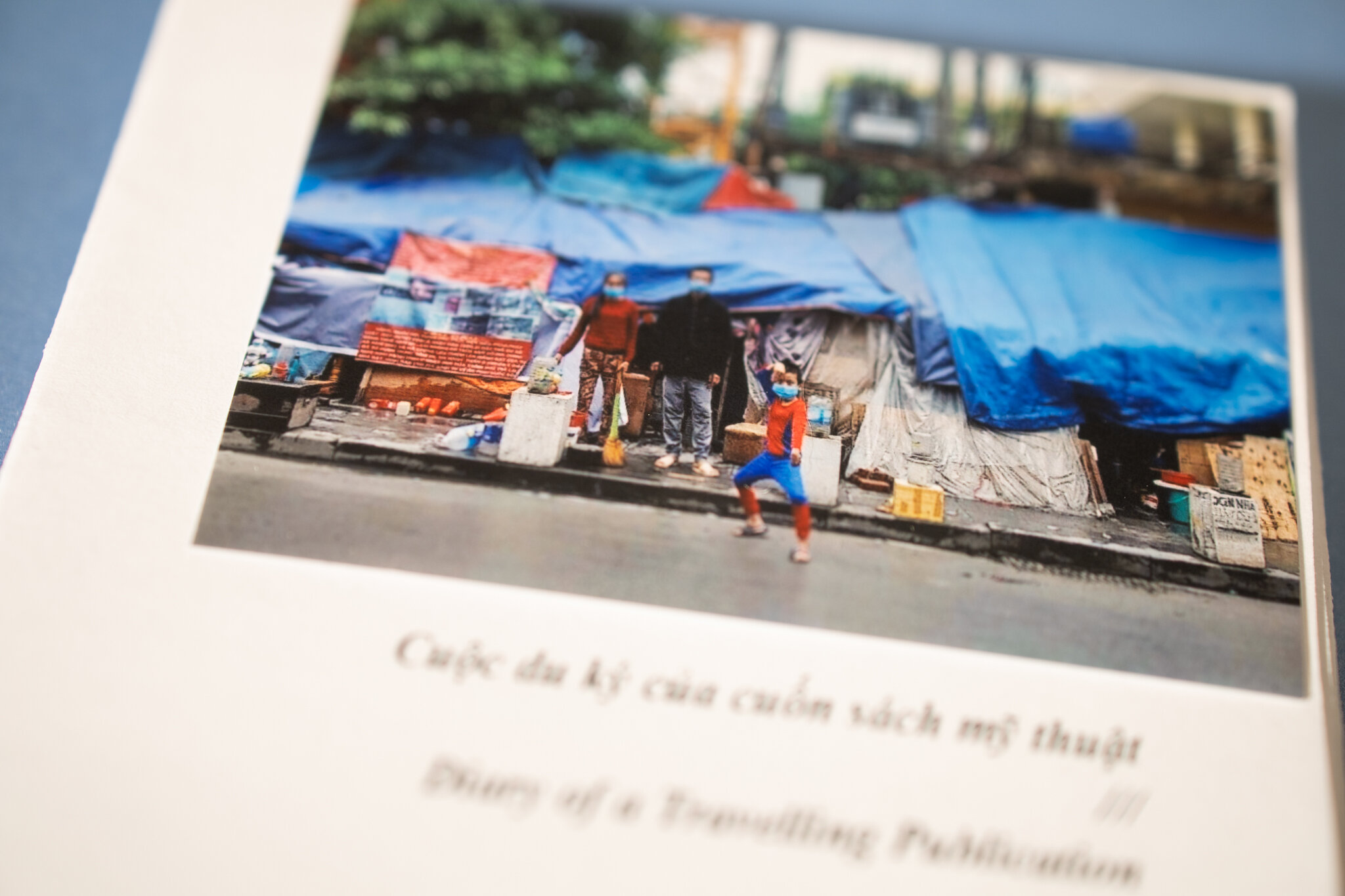

Keep this in mind as you read through this Martha’s Quarterly. Its design is meant to slow the reading of its words. When you first see this book, you’ll notice that it is bound with a cinnamon stick, meant to allude to Sanchez’s performance. The stills from his performance wrap around Duplan’s erasure poem, which pockets Le’s narrative. When you open Sanchez’s written reflection on his performance, you’ll notice that some words can only be read by taking the mirror from the cover and looking at its reflection. Once you find Lê’s narrative, you’ll also find a small photograph of a masked family during quarantine in Vietnam, further connecting these issues of expression to public safety.

In the 17th century, when the plague was reaping its way through Europe, a full-body-suit costume was designed by the physician Charles de Lorme for doctors to tend to the needs of European royals. One of the most iconic features of this suit was a mask with a foot-long beak-like shape. Physicians believed that the plague spread through the air-- similar to the droplets that spread COVID-19-- and so this bird mask protected the doctor’s face from contamination through the air. Today, it is mandatory to wear a face mask to enter a grocery store in New York City, a habit that many folks living in Asia have been accustomed to for a long time. It is a strange contradiction that you must mask yourself in order for your community to move freely, or in order for the doctor to see you so that you can mend. In a way, we are set free by our mouths, through the things that we say and the contagions that we could spread. This is why this Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 15, Spring 2020, is called Mouth to Mouth. Through these presentations, Passenger Pigeon Press hopes that this issue will probe at these ideas about freedom, and how our mouths are the vessels for freedom to prevail.

- Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief