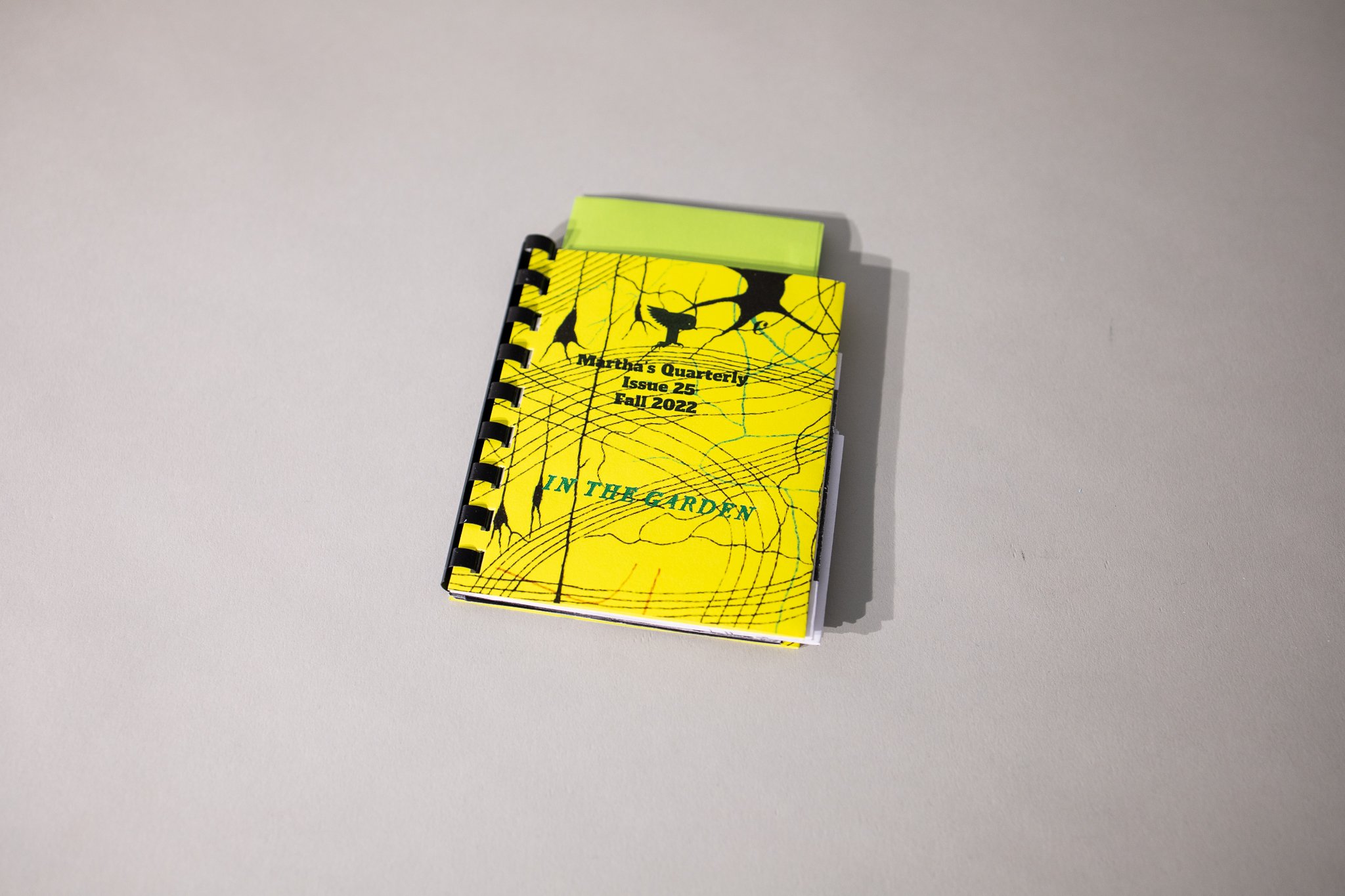

MQ 2022

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 25

Fall 2022

In the Garden

5” x 4”

About the Contributors:

James S. Bielo is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Miami University. He is the author of five books, most recently Materializing the Bible: Scripture, Sensation, Place (Bloomsbury, 2021).

Gio Panlilio (b. 1994) is a curator, photo editor and artist based in Manila, Philippines. He is the Co-Founder of Tarzeer Pictures, a Production Agency and Photography Platform dedicated to the development of Filipino Photography, and is a founding member of Fotomoto. His work has been exhibited in galleries locally and abroad.

Santiago Rámon y Cajal was a scientist and artist responsible for the Neuron Doctrine.

When my aunt was dying of cancer, her caretaker knew exactly when her last day would be based on the way she was declining. 48 hours before her passing, my parents were able to prepare my aunt’s tiny apartment where she laid on her deathbed with objects and adornments that would help her transition into a happy afterlife. We prayed with our Buddhist master from the Vietnamese pagoda who came to the apartment and led a few hours of chanting. There was an auntie who I didn’t know so well, but she was a friend of my parents and seemed to know a lot about the practices surrounding death and Vietnamese Buddhist traditions. It was late at night, and we all gathered around my aunt, who was wrapped in a golden yellow cloth with red ornaments and symbols printed all over; a recording of Buddhist chants played on a tiny speaker repeatedly. Her eyes had been closed for so long they looked like they were painted on her pale white-green face. At one point, the auntie signaled to us and said it was time: my aunt will die within the next few minutes. When this happened, the auntie and my parents all started to yell into my aunt’s ears to look into the light: “Don’t look anywhere else! Look directly into the light, into the light!” they all cried. The cries were fanatic and their faith was certain.

Over the last few years in my artwork and in a few of the past Martha’s Quarterlies, I have been asking questions about faith: How do we believe? How do we express those beliefs? By extension, I am also probing at the question of truth, a subject that sits at the core of many cultural and ideological divides today.

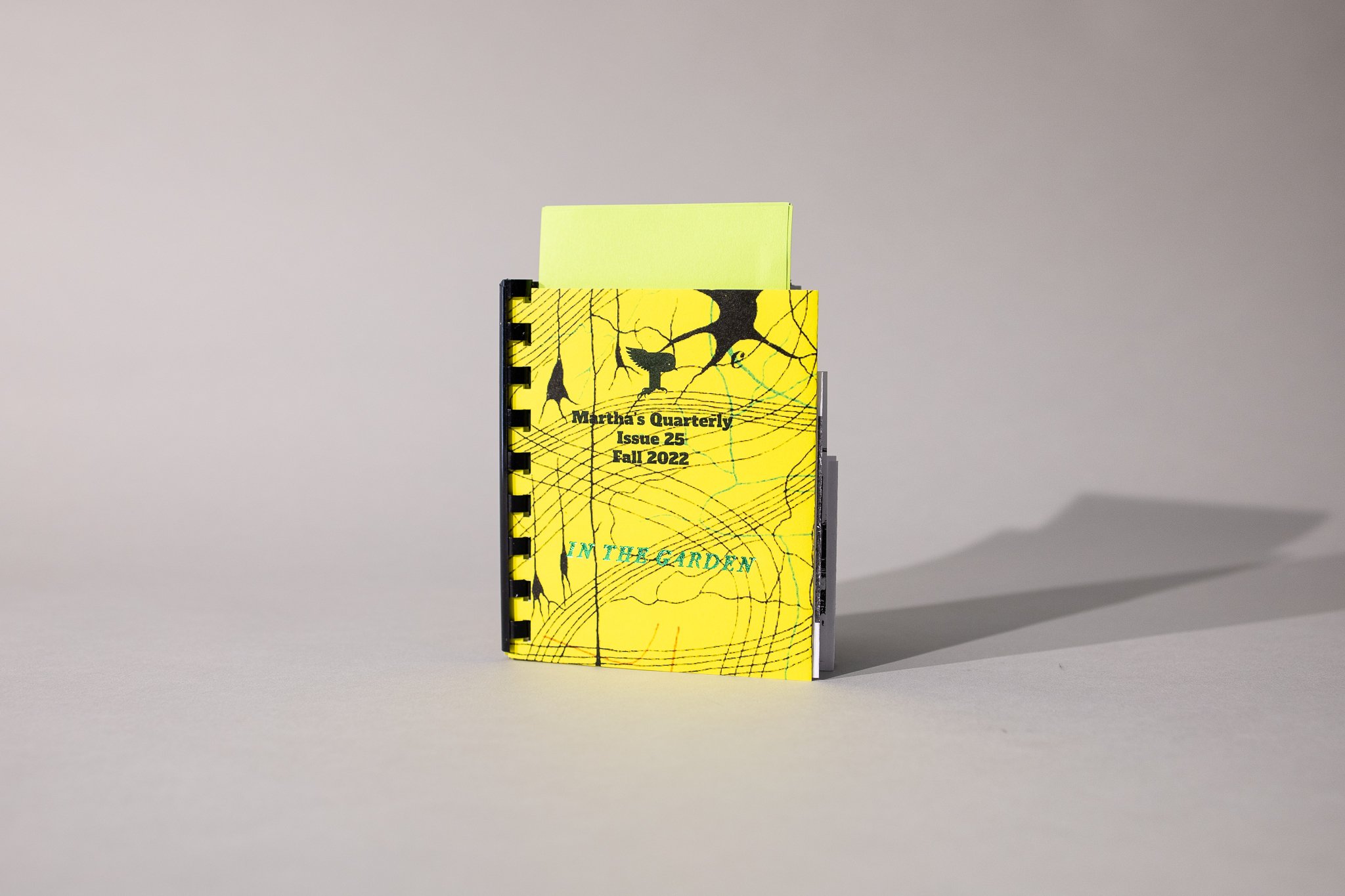

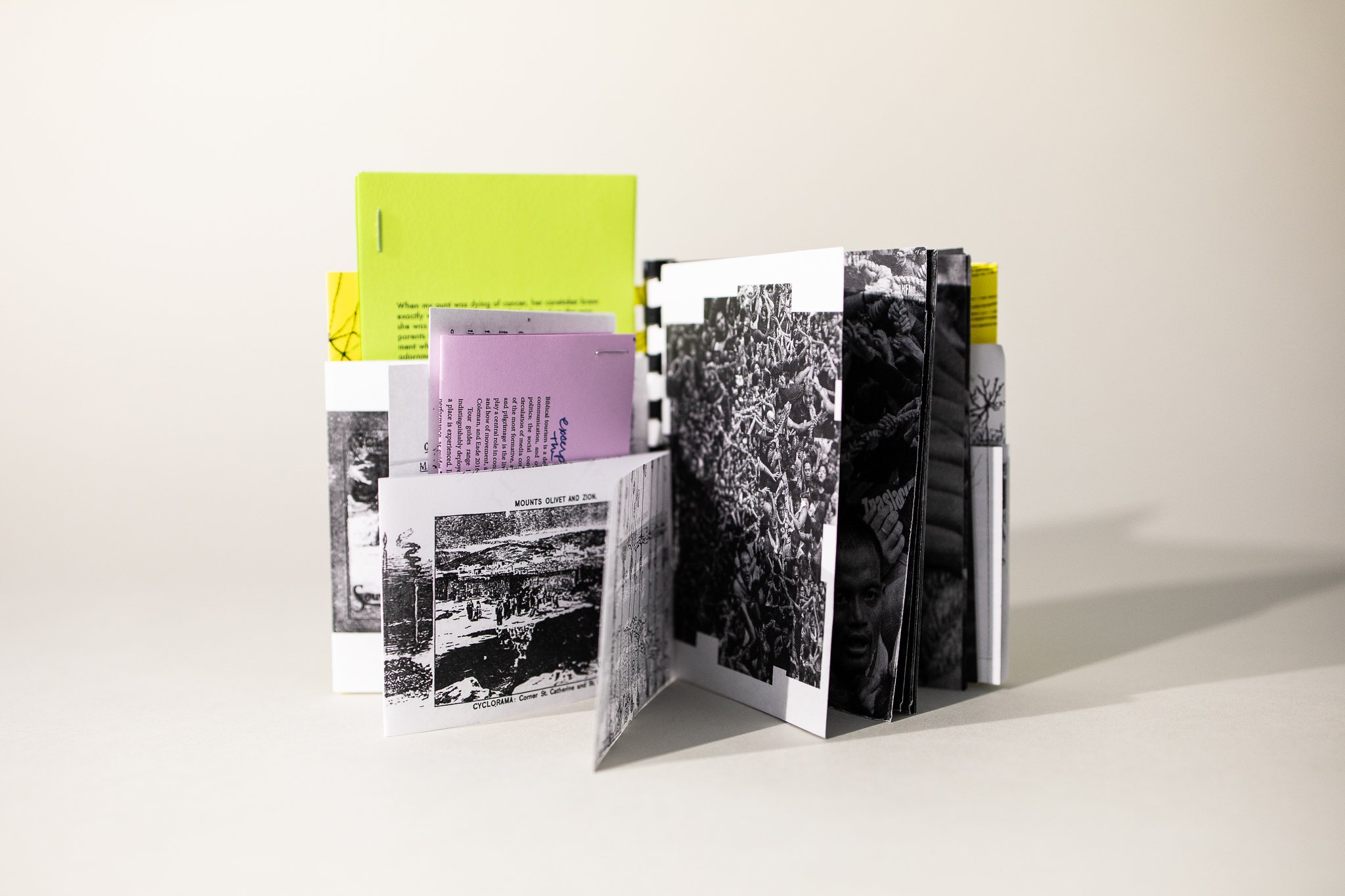

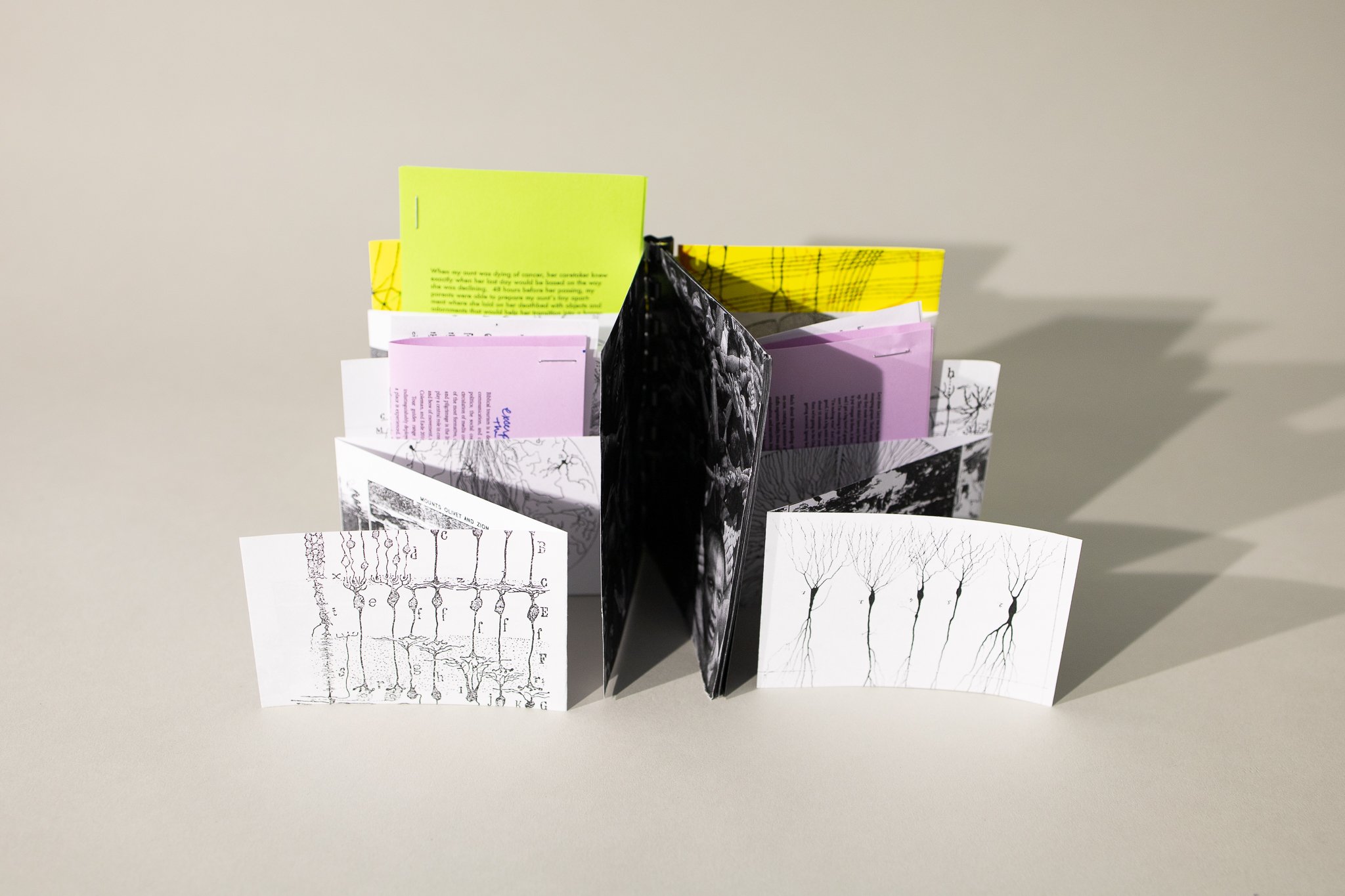

My memory of my aunt’s passing consists of many acts and objects that constructed how my family’s faith was expressed. The brass of the chanting bowl, the printed silk that wrapped her frail body, the plastics and wires making up the speakers that replayed the Buddhist prayers are all man-made material objects imbued with tradition and story. Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 25, Fall 2022, In the Garden, explores the human phenomenon of expressing faith through materiality, such as through physical objects that become experiences.

This issue takes its name from an essay by anthropologist James Bielo that was included in his recent book Materializing the Bible, wherein he explores how the Bible and the Christian faith has been manifested through material objects. In his essay, Bielo takes us to Covington, Kentucky, to a Christian theme park at the end of No Outlet Road called the Garden of Hope. Trees and flowers are carefully landscaped throughout the garden, with pathways leading to and framing structures and murals that all depict stories from the Bible. In one comment I found in Tripadvisor, Courtney H exclaimed: “The Holy Spirit spoke loudly to us while at this site, this site should be cherished by all and is an amazing place to worship God.” [sic] Bielo introduces us to Steve, who is a proud steward of Garden of Hope. Without any official authority–such as a class certificate or religious training–Steve is one of the garden’s experts on the history and experience of the site. What makes him compelling is own faith in God, love for the Garden of Hope, and endearing way of telling visitors the stories about the place and about God.

What is intriguing to me is how many eager visitors to the Garden of Hope leave with even more excitement and elation for their faith. I think this has something to do with the power of storytelling coupled with its physical manifestation. Describing the tomb of Jesus, MsPearl105 also commented on Tripadvisor: “The visionary laid the foundation for this quaint but powerful replica. How can any believer stand on the hill and not marvel at God’s awesomeness. Even the Cincinnati skyline is a work of His hands for it is He who gave man the ability to create. The sky and clouds tell of His glory. The empty tomb replica resonated especially deeply since it was, after all, that Jesus followers found visited His empty tomb!”

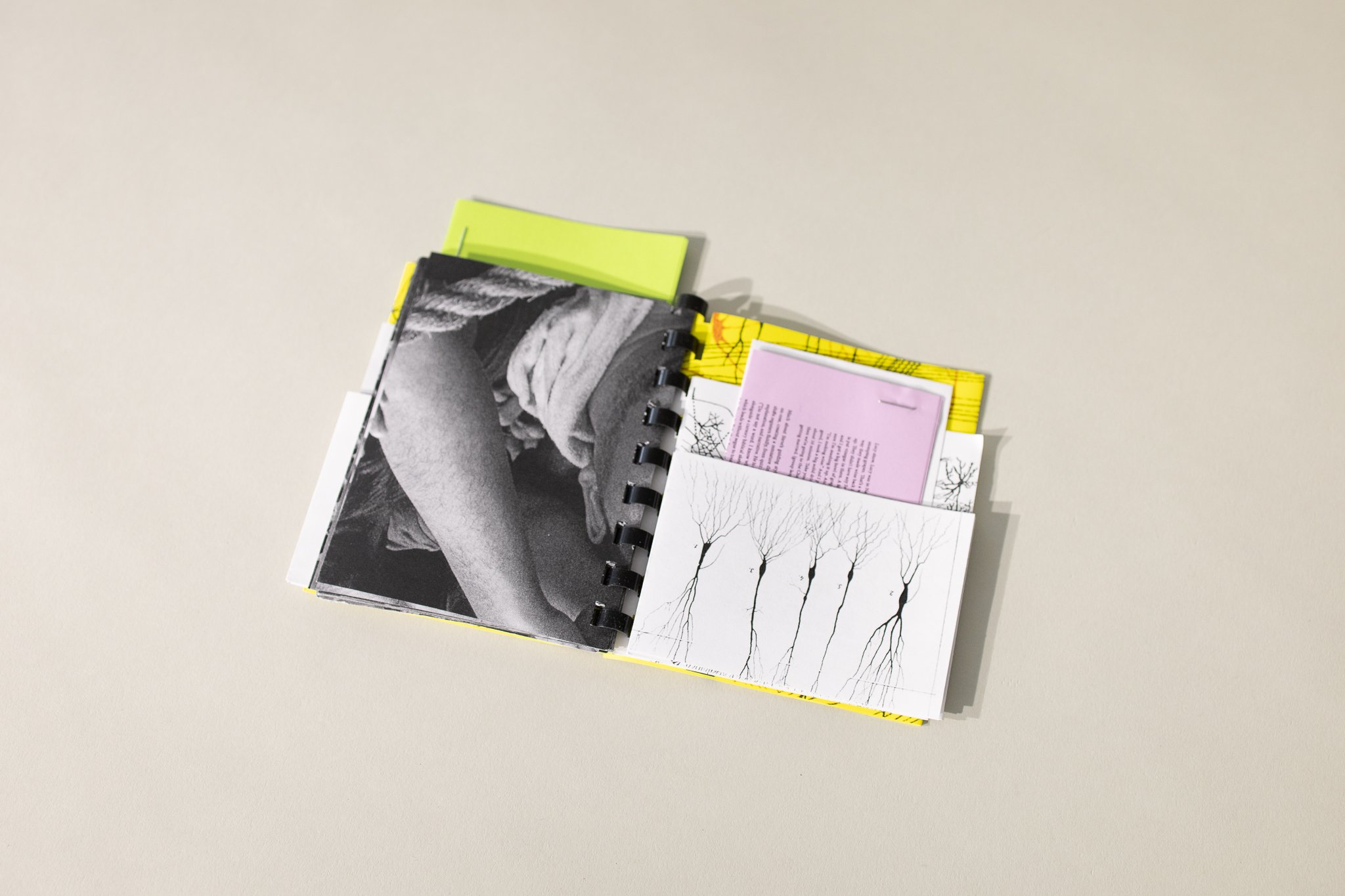

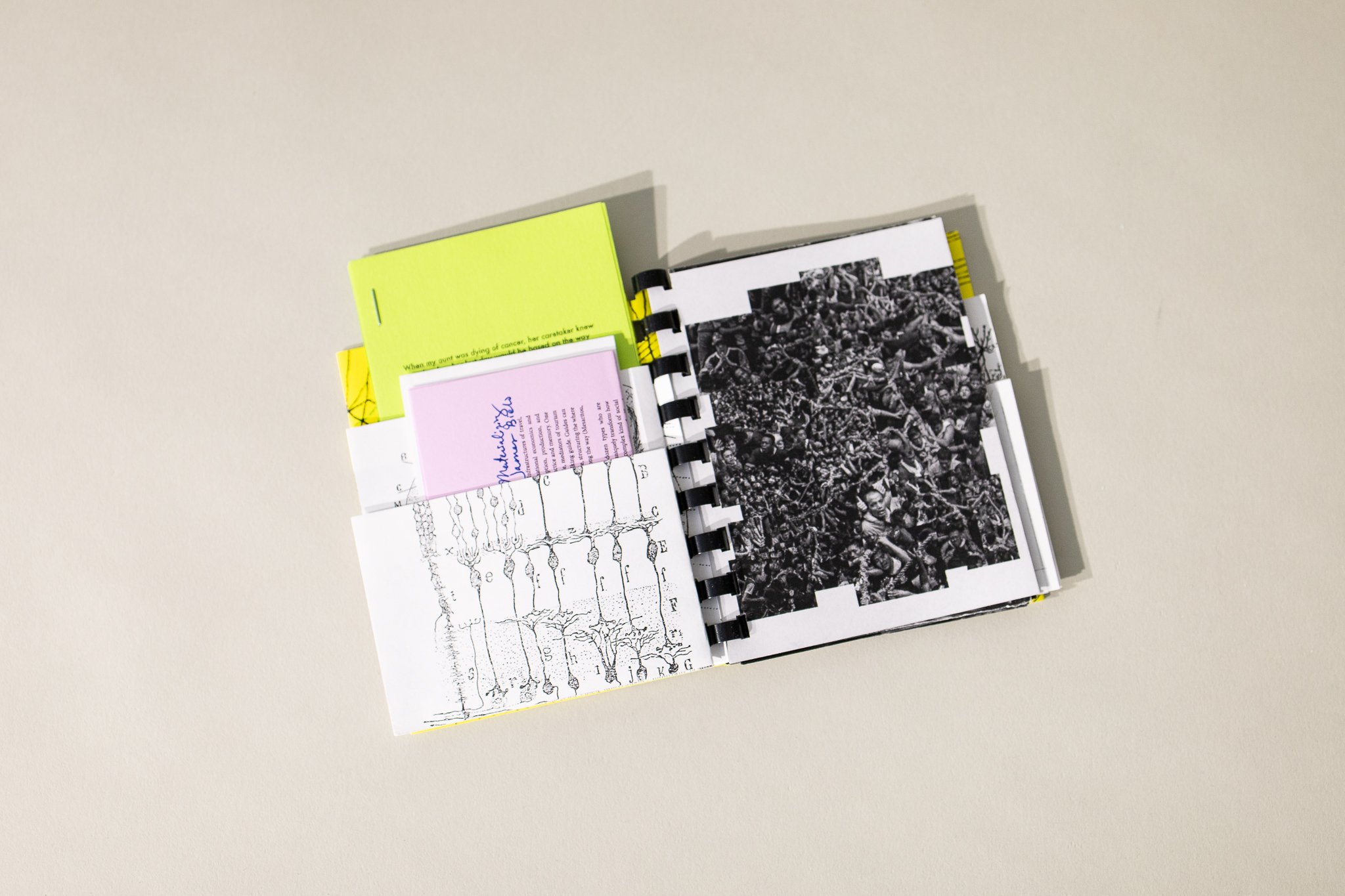

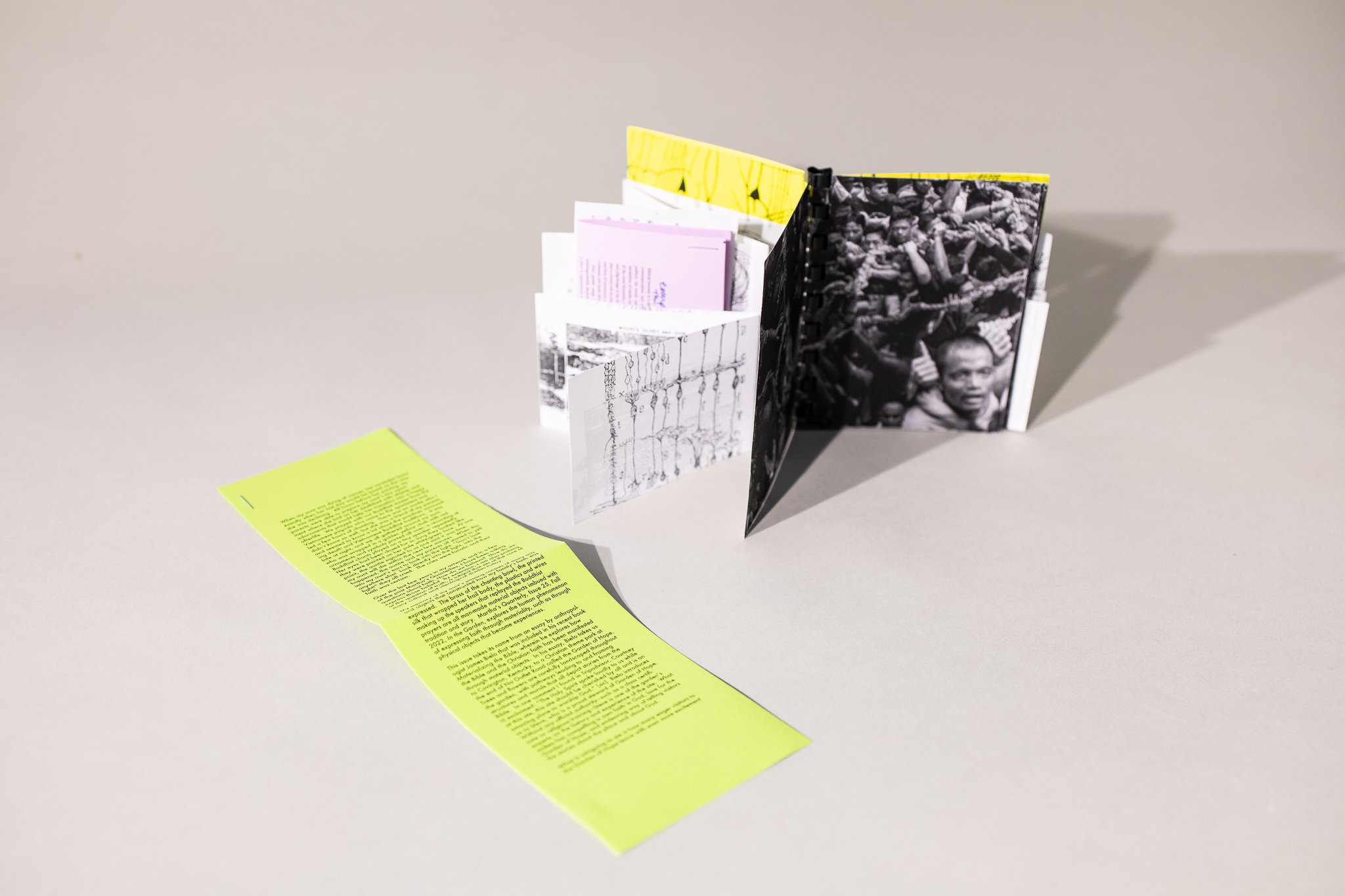

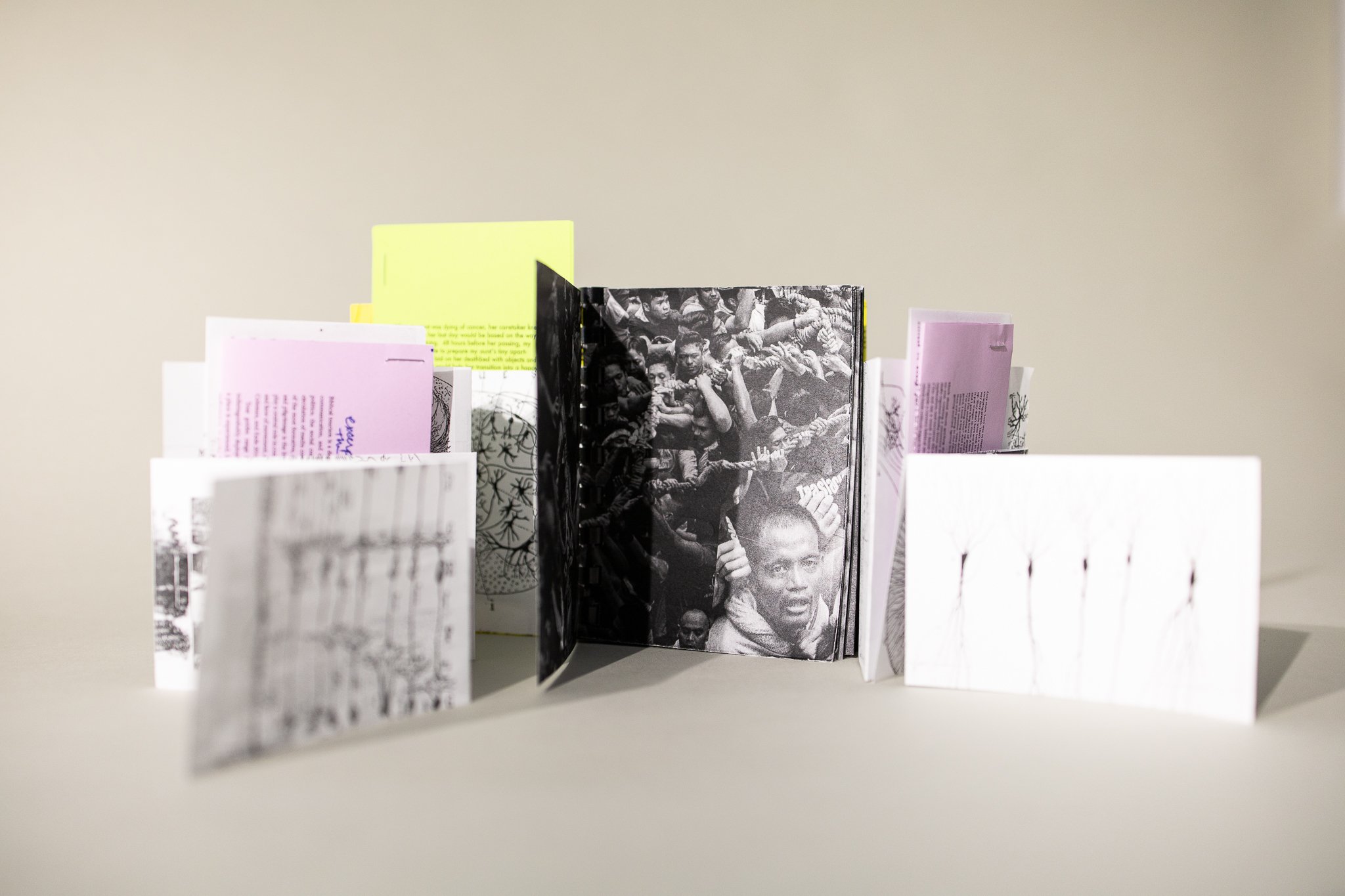

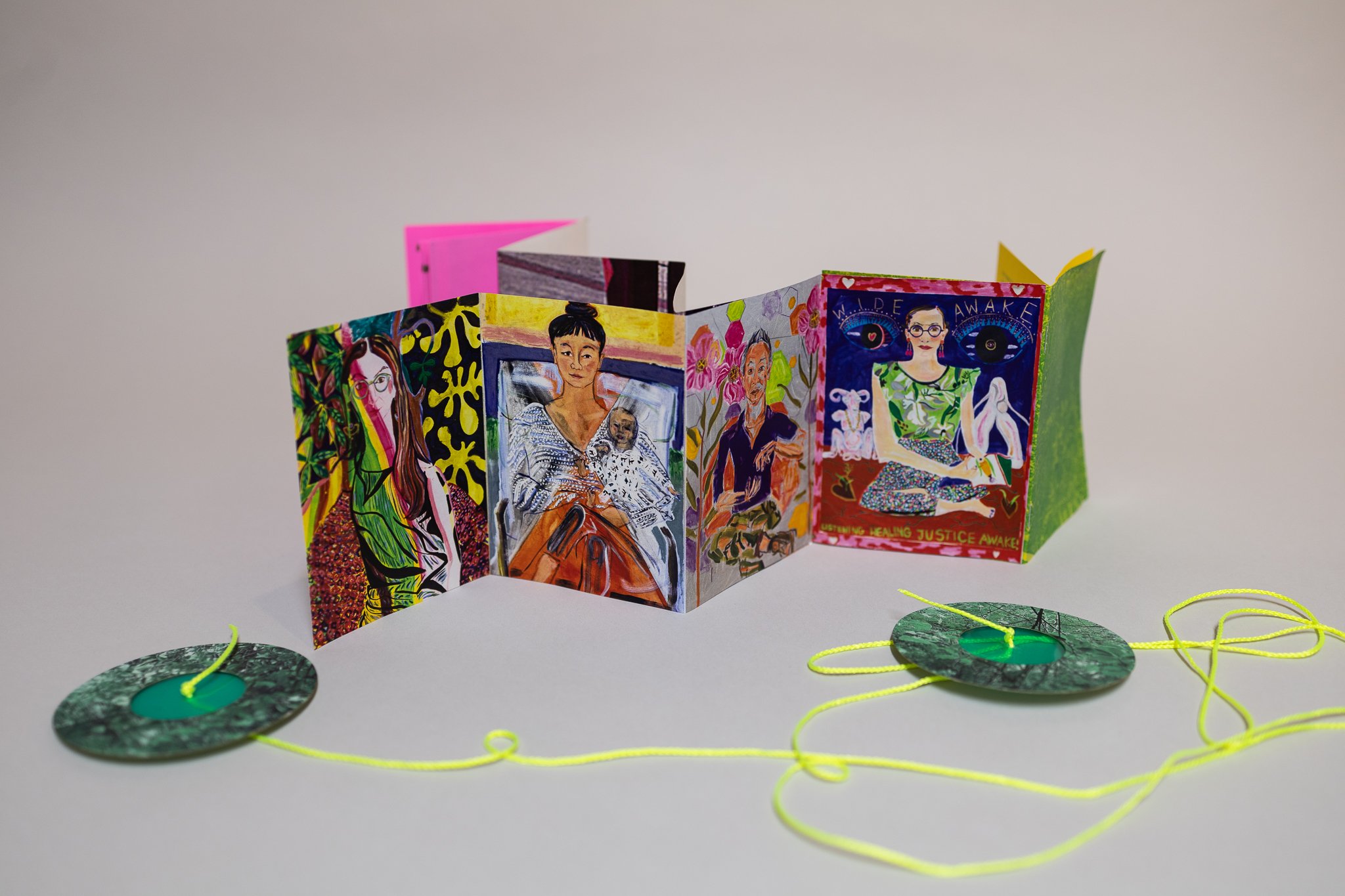

It seems to me that sites–whether it is elaborate like the Garden of Hope, my aunt’s living room, or a modest table made into a place of worship with a wooden crucifix or a ceramic Buddha–have the capacity to activate stories. Without a site, there is no place for stories to be “lived out” in real time. Even a captivating storyteller benefits from a site as a place for folks to gather to learn of traditions and miracles. The idea of a religious site is one of the reasons I was moved by Gio Panlilio’s photograph Swell, where he has collaged aerial photographs of many worshipers swarmed around the Feast of the Black Nazarene that occurs every January in the Quiapo district in Manila, Philippines. We took Panlilio’s photograph and zoomed into many areas of it. As you flip through the center booklet, you can see details of hands and faces, many of which are stressed in some way: faces are screaming, wailing, and crying; many hands are grasping, reaching, and slipping.

Brought to the Philippines from Mexico by Spanish missionaries in the 17th century, the Black Nazarene was a lifesize statue of Jesus that survived a terrible fire, giving it its stark black color. Many believe this statue holds powers that can wash away sins and cure illness. The statue lives in a church in Quiapo and draws thousands of people on the feast day to activate the story again and again. What is peculiar to me in this photograph is the complete absence of the Black Nazarene statue that this entire festival is centered around: it is almost as if the materiality of Christianity was so powerful that it inspired a level of passion which no longer needed physical props or storytelling.

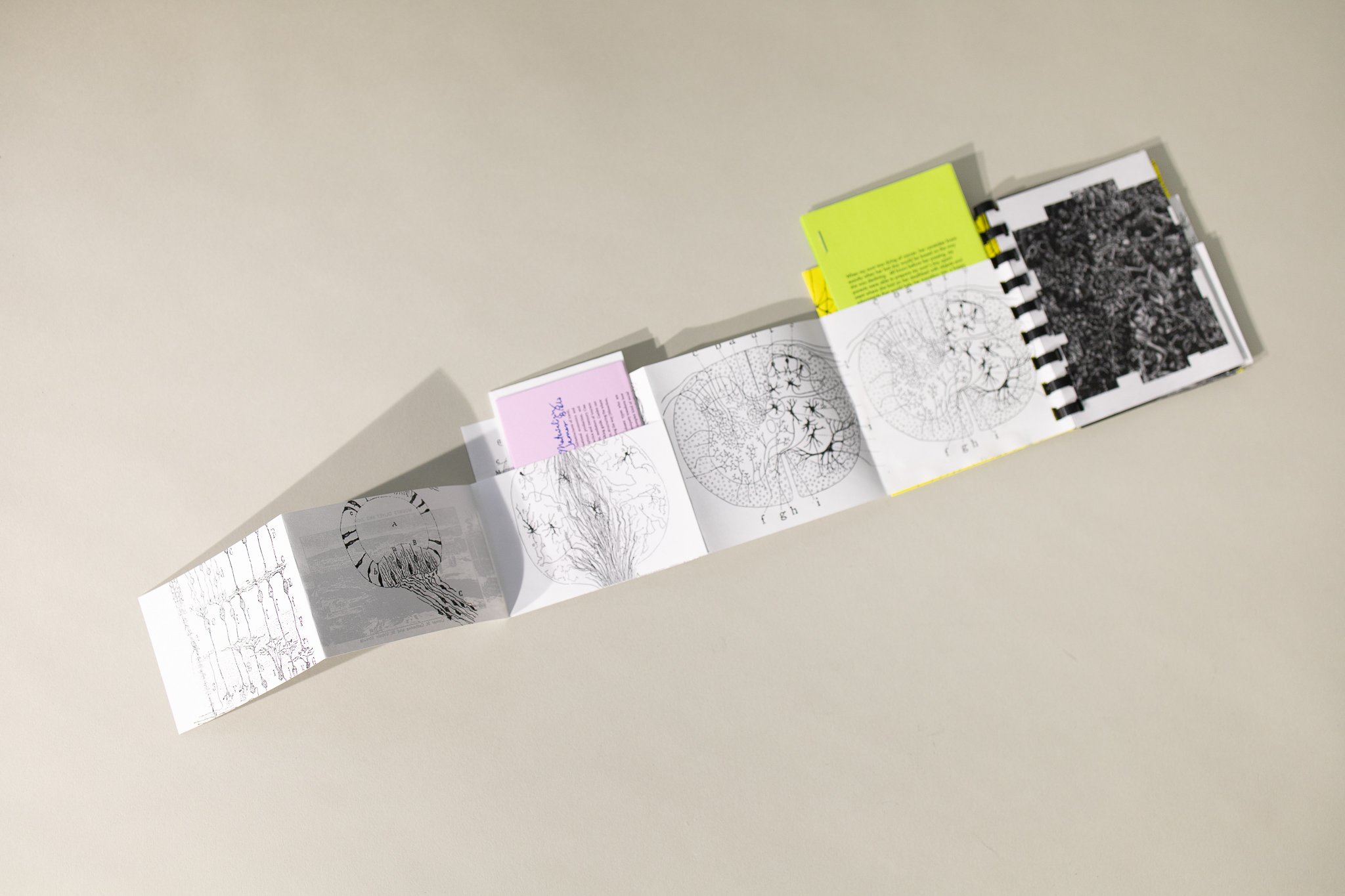

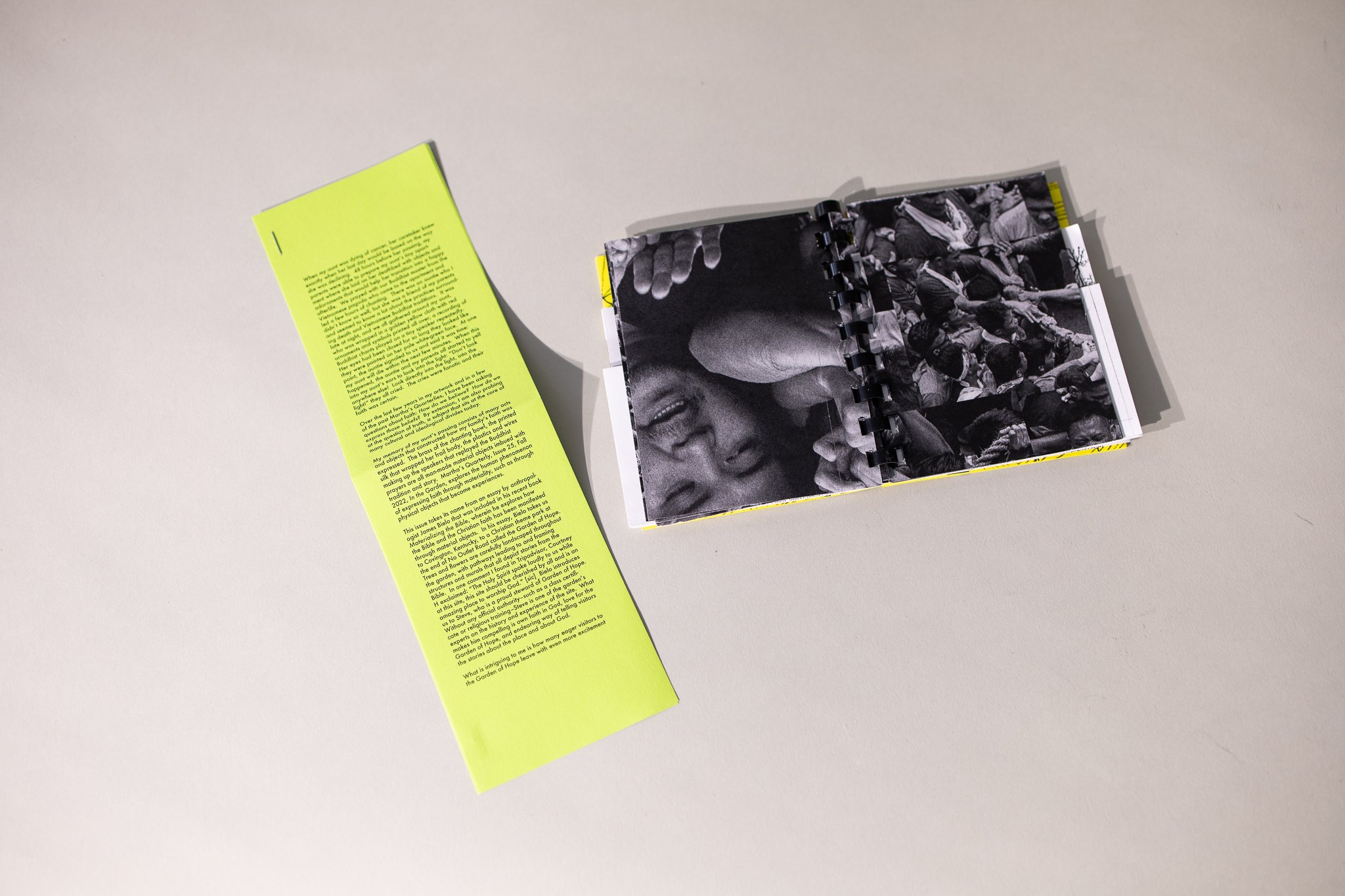

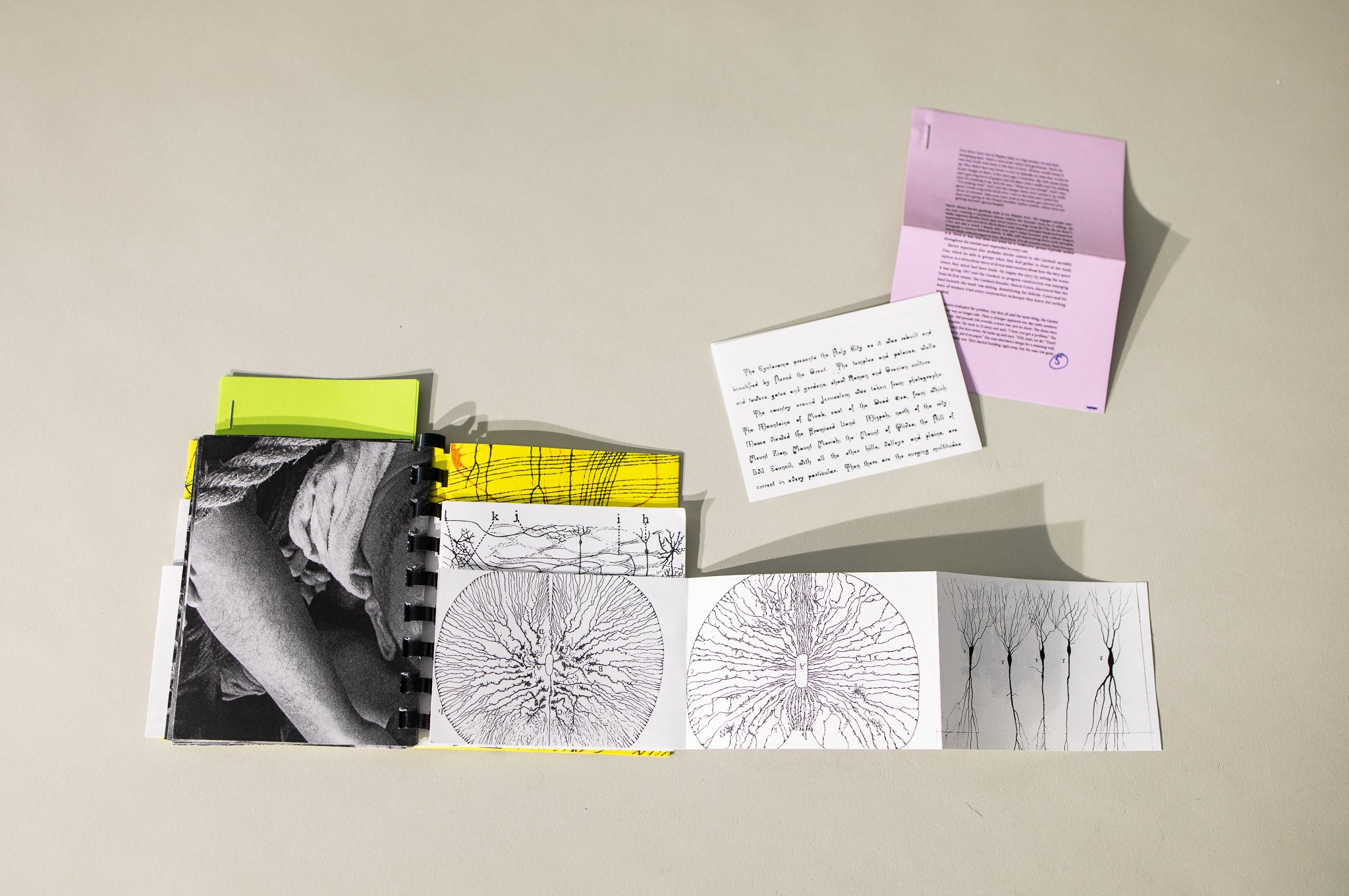

Do you have to see it to believe it? Collaged all over the wings of this Martha’s Quarterly are drawings of brains by Santiago Ramón Cajal and reproductions of paintings at the Cyclorama of Jérusalem in Montreal. This comparison aims to juxtapose narratives of faith and science through artistic manifestations. These man-made images help audiences believe in two subjects that cannot be seen: the workings of the insides of a brain and God. Regarded as the father of modern neuroscience, Santiago Ramón Cajal was a scientist and artist who discovered that the brain was made up of individual nerve cells, i.e. neurons. Using staining techniques that allowed him to see the brain in fresh detail, he observed that the brain was not made up of continuous cells, but rather that the cells were separated by gaps, which eventually became known as the Neuron Doctrine. The drawings throughout this zine are cropped reproductions of his drawing studies of the brain.

Cajal said, “The cerebral cortex is similar to a garden filled with innumerable trees, the pyramidal cells, which can multiply their branches thanks to their intelligent cultivation, send their roots deeper, and produce more exquisite flowers and fruits every day.”¹ Let’s consider the brain’s exquisite flowers and fruits as creativity. Organized religion has been greatly evolved through artistic processes, from the way language is used to write and tell sacred stories to the ways in which religious buildings are constructed and decorated.

The Cyclorama of Jérusalem is North America’s largest panorama and depicts Jerusalem during the time of Christ’s crucifixion. The souvenir pamphlet has been reproduced for this zine, with the text folded into the wings and the images spread across the front and back cover fold-outs. Based on original paintings by the German painter Her Bruno Piglhein, this reproduction wraps 360 degrees around the viewer and spans more than 16,000 square feet. It is so large and illustrative that many visitors feel that they are “reliving” Christ’s death in Jerusalem. In the pamphlet, there is a quote by a former Turkish soldier, J. Drew Gay:

“During the period of my service in the Turkish army, I had occasion to visit the Holy Land in a professional capacity, and having just seen your Cyclorama of Jerusalem on the day of the Crucifixion, am able to testify to the astonishing vraisemblance of the illustration. Eastern scenes are usually depicted in so grotesque a manner as to draw the derision of all Oriental travellers. But the people, the caravans, the buildings and the general tone of both buildings, atmosphere and costumes in your Cyclorama are so true that the spectacle is both admirable and instructive.”

I think that Colonel Gay’s felt truth is what acutally sits at the core of all the elements in this issue of Martha’s Quarterly. From my aunt’s deathbed, to the Garden of Hope, to the Feast of the Black Nazarene, to the brain drawings, and Cyclorama, truth is felt, largely because of something that was physically and artistically created by man. As a result of materiality, particular narratives of faith and science are able to evolve, often ultimately being able to live on without the material manifestation that made the story so true in the beginning.

–Tammy Nguyen

Editor-in-Chief

1. Cajal, Santiago Ramón y, et al. The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Harry N. Abrams, 2017. 61.

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 25, Fall 2022, In the Garden is a comb-bound booklet with fold-outs and inserts. Most of the content was digitally printed with the exception of the title, which was hot stamped in hand-set type. All of the papers used were 20 lb text weight in yellow, green, purple, and white colors. The works of James Bieolo and Gio Panlilio were adapted with their permission. The drawings by Santiago Rámon y Cajal and reproductions from Cyclorama of Jerusalem are part of the Public Domain. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen. Production was led by Holly Greene with assistance from Téa Chai Beer, Clara Burger, Lucy Hoffman, Mely Kornfeld, and Robie Scola.

Published October 2022, edition of 200.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 24

Summer 2022

They’ve Drank the Cockagee

4.25” x 4”

About the contributors:

Jacob Cline grew up in Cocoa Beach, Floria and drew inspiration from surfing and his parents’ garden, exploring the connections between fantasy and reality. Jacob resides in Brooklyn, NY and fishes in the East river every weekend.

Mark Jenkinson produces premium craft cider on his historic Farm just outside Slane in County Meath using apples from his own orchards.

A few weeks ago I visited Birr Castle, located in a town called Birr in County Offaly, Ireland. Today, the 7th Earl of Rosse lives there with his family, with a large portion of the grounds being accessible to the public. Birr Castle is particularly famous for its contributions to astronomy: one of its main attractions is “The Leviathan,” which was the largest telescope in the world when it was built by the 3rd Earl of Rosse in 1845 and remained so for 75 years. Walking around the castle displays, there were hundreds and hundreds of projects to marvel at. Rooms were filled with sundials, handheld telescopes, and other measuring devices. One of the most instrumental technologies developed here was “great reflectors,” large silver reflective disks that were used in the telescope to see beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

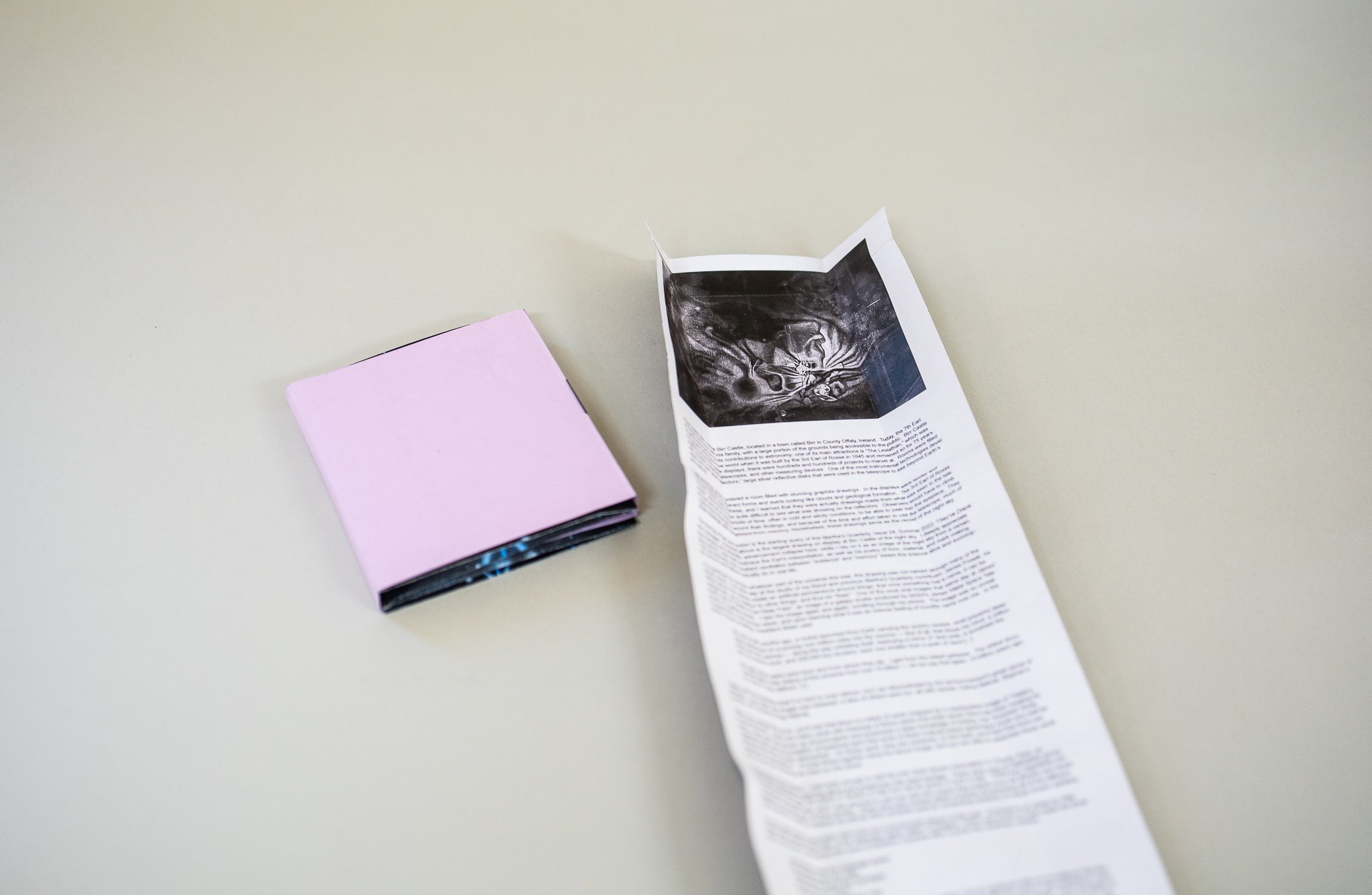

I was awestruck when I entered a room filled with stunning graphite drawings. In the displays were tender and tedious drawings, the abstract forms and swirls looking like clouds and geological formation. The 3rd Earl of Rosse himself created many of these, and I learned that they were actually drawings made from what was seen in the telescope. Many times, it was quite difficult to see what was showing on the reflectors. Observers would have to climb 60 feet and sit for long periods of time, often in cold and windy conditions, to be able to peer into the eyepiece. They made these drawings to record their findings, and because of the time and effort taken to use the telescope, much of these drawings were completed from memory. Nonetheless, these drawings serve as the record of the night sky.

The blurring of fact and fiction is the starting query of this Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 24, Summer 2022: They’ve Drank the Cockagee. Pictured above is the largest drawing on display at Birr Castle of the night sky. I deeply appreciate how fantasy and scientific advancement collapse here: while I rely on it as an image of the night sky from a certain time period, I also fully embrace the Earl’s interpretation, as well as his poetry of form, material, and mark making. This simultaneity, this constant oscillation between “evidence” and “memory” keeps this science alive and evolving–as science and Nature actually do in real life.

It is significant to me that whatever part of the universe this was, this drawing was not named (though many of the others were). The other day at the studio of my friend and previous Martha’s Quarterly contributor, James Prosek, he talked about how names create an artificial permanence around things: that once something has a name, it can be categorized, put in relation to other things, and thus be “fixed.” One of the most viral images that same day at James’ studio was of “Webb’s First Deep Field,” an image of a galaxy cluster produced by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope of a galaxy cluster. I saw the image again and again, scrolling through my phone. The image was so unreal: it looked like a cool screen saver, and upon learning what it was an intense feeling of humility came over me. In the White House unveiling, President Biden said:

Six and a half months ago, a rocket launched from Earth carrying the world’s newest, most powerful deep-space telescope on a journey one million miles into the cosmos — first of all, that blows my mind: a million miles into the cosmos — along the way unfolding itself, deploying a mirror 21 feet wide, a sunshield the size of a tennis court, and 250,000 tiny shutters, each one smaller than a grain of sand [...]

But light where stars were born and from where they die. Light from the oldest galaxies. The oldest documented light in the history of the universe from over 13 billion — let me say that again: 13 billion years ago. It’s hard to even fathom. (1)

I agree with the president that it is hard to even fathom, but I am discomforted by the announcement's great sense of certainty. Soon after that image was released, a slew of others were too, all with names: Carina Nebula, Stephan’s Quintet, and Southern Ring Nebula.

When you unwrap this issue, you’ll see that there is a stack of cards wrapped by a manipulated image of “Webb’s First Deep Field.” Inside are many cards with drawings of fictive plants that artist Jacob Cline has been creating for years. Cline, who has grown up around plants and possesses a deep knowledge of botany, has “invented” these organisms with such a foundation of botanical parts that some of these tropical-esque specimens could very well be species that have not been discovered. On these cards, they are unnamed; on the back, you’ll find that there are swatches of “atmosphere.” Puzzle these together using the above image, and you are able to assemble these cards into the 3rd Earl’s drawing as seen on this sheet.

On this same trip to Ireland, I was lucky enough to visit the Irish Seed Savers Association in County Clare, an organization dedicated to learning about and preserving Irish seed heritage. There were rows of vegetables grown for seed–I had never seen the plants or flowers of kale and carrots grown in such a way. These two vegetables are so common in my world view, and I was stunned to see how wild and unique they looked once the flowers and seeds appeared in the later cycle of their growth. There were also verdant apple orchards documenting all of the different native species of apples in Ireland, as well as other orchards used for conducting research on lesser known varieties.

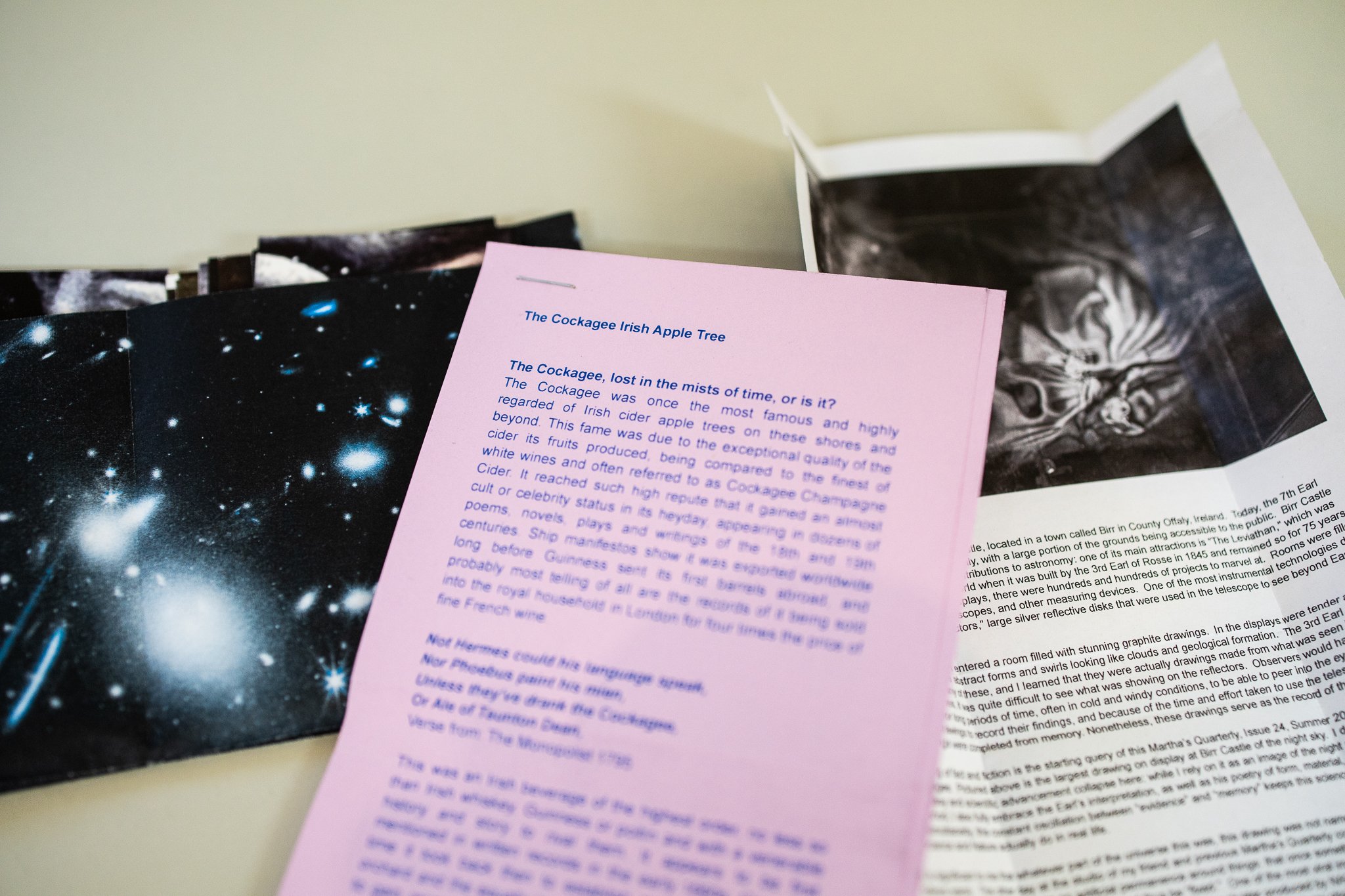

The Irish Seed Savers Association also puts out a journal each season of the year. Enclosed is an essay by cider maker Mark Jenkinson that tells of the legendary apple called “Cockagee,” which was known to have made the finest ciders ever known. We named this issue of Martha’s Quarterly after a quote that Jenkinson shared:

Not Hermes could his language speak,

Nor Phoebus paint his mien,

Unless they’ve drank the Cockagee,

Or Ale of Taunton Dean,

Verse from: The Monopolist 1795

For decades, the Cockagee species came to be “known as extinct,” but as Jenkinson tells us, he believes that this is not the case based on another species of apples that appeared under a different name in Gloucestershire–Hens’ Turds, as opposed to the English translation for the Irish name for the Cockagee, Cac a ghéidh, which translates to Goose Turds. As Jenksinon describes, it seems that this other apple is indeed the Cockagee, but there is no way to prove this through DNA unless another of the same tree appeared in Ireland. I want to draw attention to the use of names in this context: because the two apples have distinct, if similar names, there is an implied permanence to their being different species, though Jenkinson knows deeply that these names do not reveal the truth about these species–that the truth is that they are the same tree, despite however they are named.

All of this being said, names are useful. They give us a sense of direction, helping us to make decisions. If only we were not so beholden to them.

Before President Biden gave his remarks about the Webb Space images, Vice President Kamala Harris also had some remarks:

And now we enter a new phase of scientific discovery. Building on the legacy of Hubble, the James Webb Space Telescope allows us to see deeper into space than ever before and in stunning clarity. It will enhance what we know about the origins of our universe, our solar system, and possibly life itself. (1)

In the background of all of this today is the extraordinary tension in the United States with the recent overturn of Roe v Wade by the Supreme Court. Whatever side you land on, I think that naming is essential to the Court’s decision and the people’s fears, celebration, anxiety, and hopes. What does Vice President Harris mean here by “life”– what exactly do we know with such certainty? How do we name life? And do we negotiate the definition of things in relationship to the truth in which we believe?

Tammy Nguyen

Editor-in-Chief

1. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/07/11/remarks-by-president-biden-and-vice-president-harris-in-a-briefing-to-preview-the-first-images-from-the-james-webb-space-telescope/

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 24, Summer 2024: They’ve Drank the Cockagee was created using xerox on various text weight and cardstock papers. Arial font was used throughout in different sizes and styles. This issue was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen and produced by Téa Chai Beer, Holly Greene, and Maia Panlilio. It was an edition of 200.

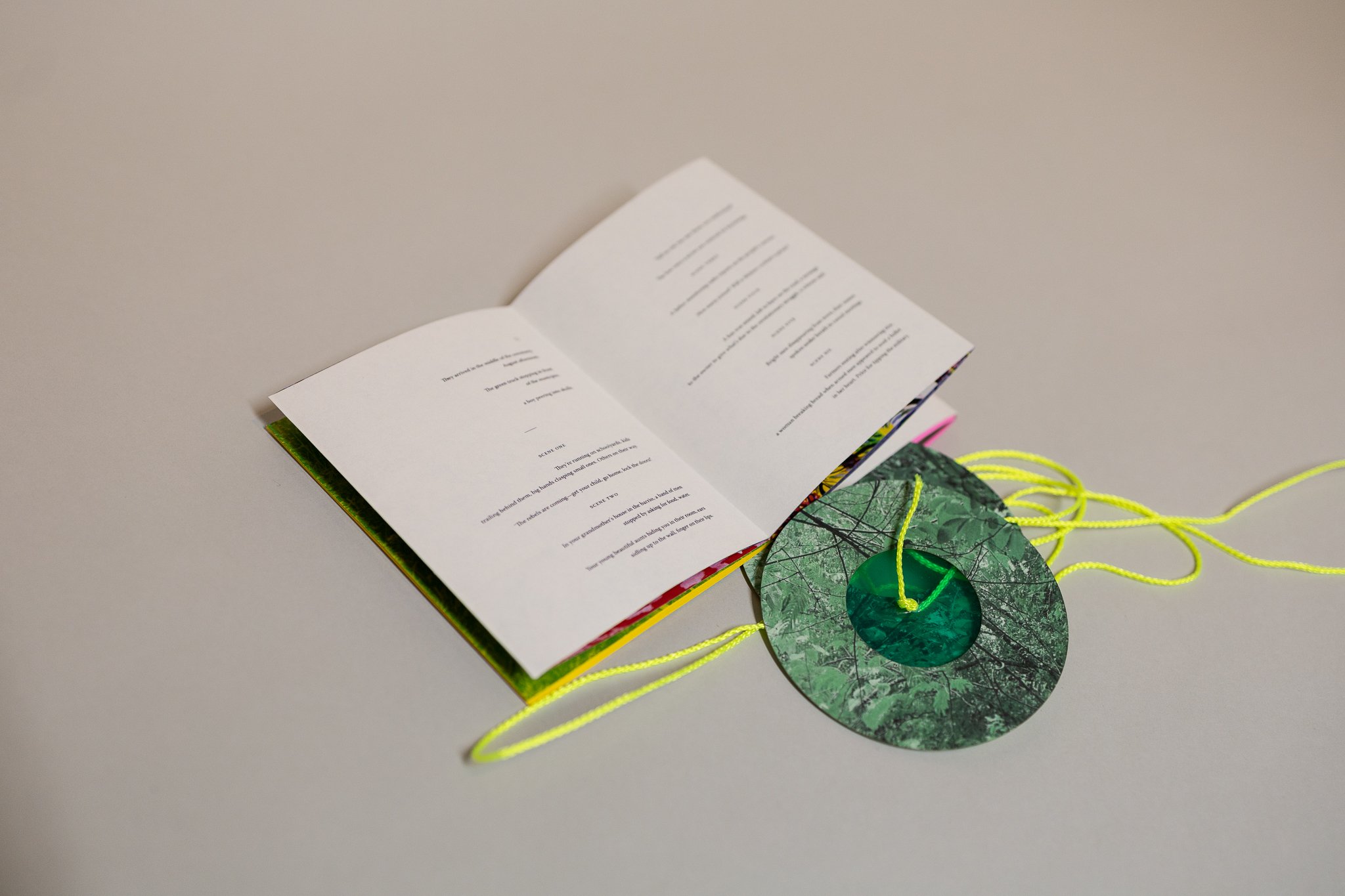

Martha's Quarterly

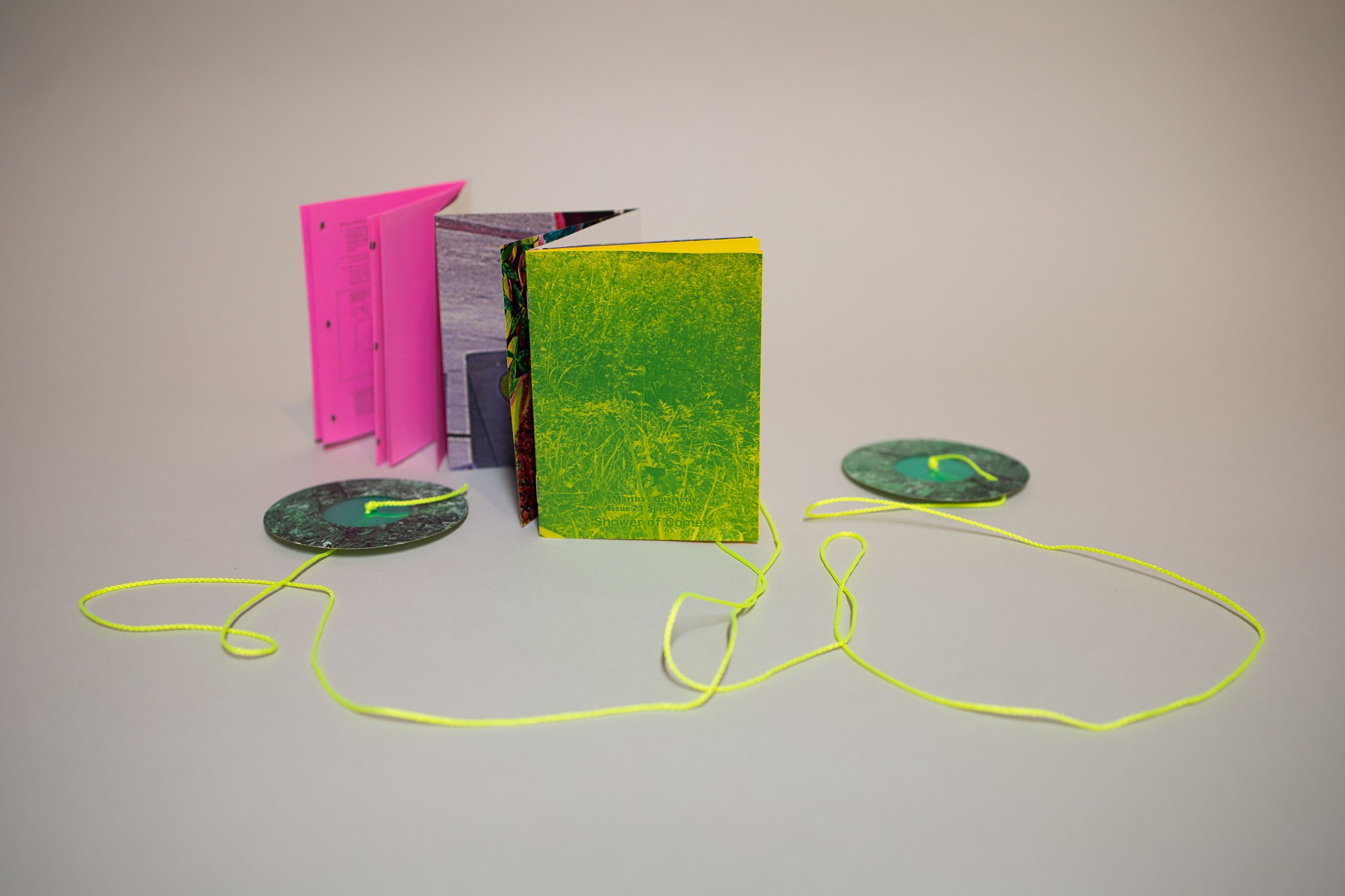

Issue 23

Spring 2022

Shower of Comets

5.25” x 4”

About the contributors:

Heidi Howard was born and raised in Queens, New York, where they still live today. Their expansive portrait practice includes conversations, ceramics and installations.

Poet, scholar, and curator, Charlie Samuya Veric is the author of four poetry books, including Boyhood (AdMU Press, 2017), where the poems featured here were originally published. He teaches at the Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines.

Around 2009 or so, I was at a party in Saigon, and the topic of the Vietnam War came up. The topic of the “war times” comes up casually, and it is common to have “the war” be spoken about in a fleeting way. Sometimes, it starts with a small remark like, “Oh, my family was for the North.” I now forget what we were talking about, but during this conversation, an older friend who was a refugee and experienced the war during his childhood said: “You know, during the war, gossip was very important. And you know who did it the most? The gold merchants, those women who sit around all day talking with each other. The Viet Cong used them as a way to send messages and secrets.”

I didn’t live during war times. I was born in America nearly a decade after the fall of Saigon, but the war framed significant parts of my upbringing that I am frequently trying to piece together. I remember, as a kid, my mom would talk about a Vietnamese fruit that you could eat to clean your teeth. The image was clear yet confusing; how could you eat any fruit during war? My imagination of war was filled with dramatic images of explosions, men, military uniforms, and a combination of carnage and formality. In the calm after a battle, I can imagine the faces of the war-torn, but the space between ordinary life and war is perplexing. How does life continue in the midst of war? This is why my friend's anecdote was so striking: it started to fill in the picture of a full life in the midst of war, gossiping and selling gold as part of a war effort, with ordinary ways to make ends meet.

Since the war started in Ukraine, I have been interested again in the space between ordinary life and war, especially since this war has mobilized social media. As I scroll, I encounter moments of mundanity coupled with the violence of war. I look through my iPhone at someone who is roaming an empty street and suddenly sprayed with bullets; then, immediately, I’ll see an image of a pregnant Ukrainian woman, a dog, children playing, and more and more. Because of these images, the way that my mind fills with my imagination of the war in Ukraine is entirely different from the ways in which I have constructed images of wars in the past.

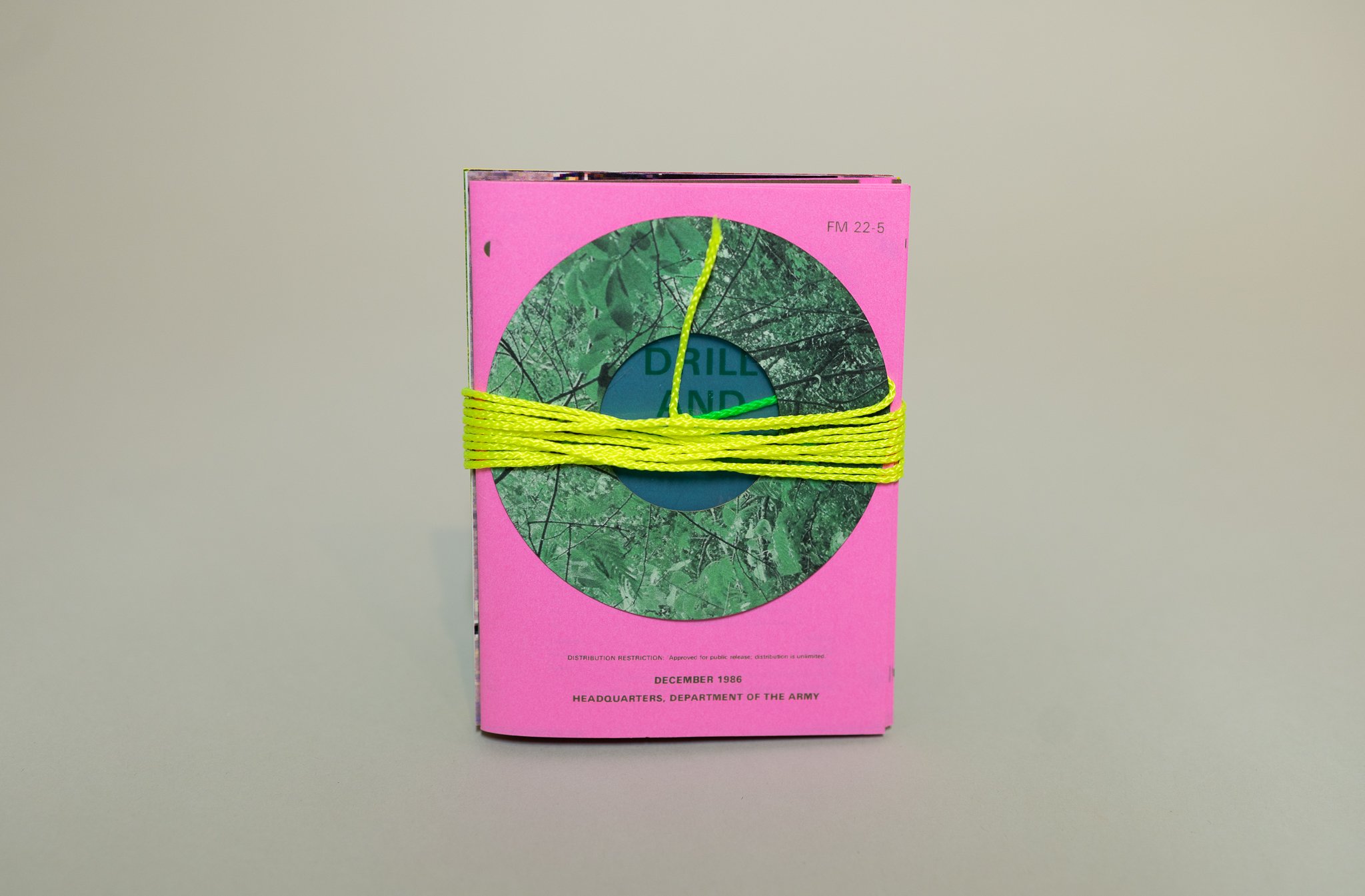

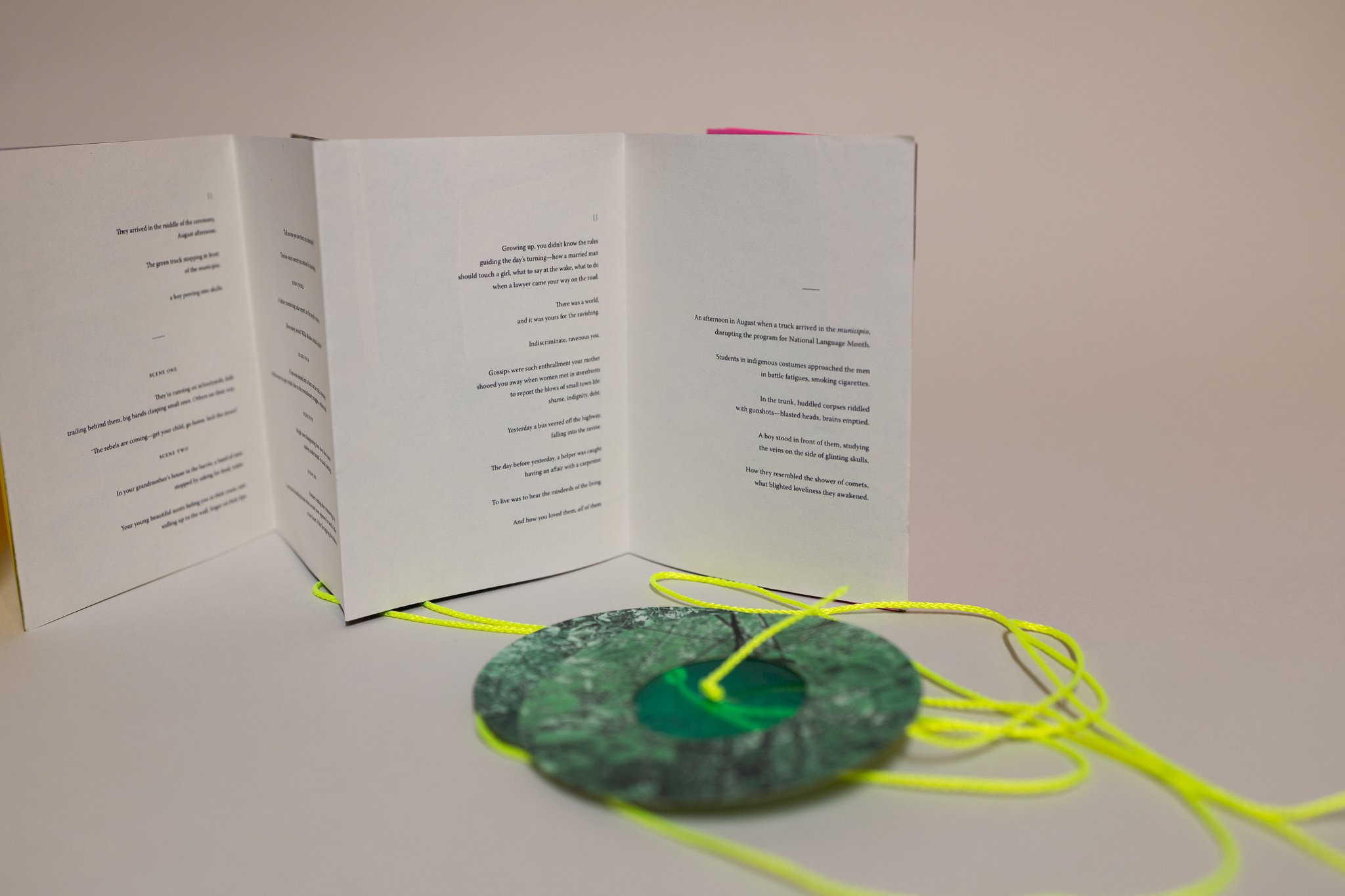

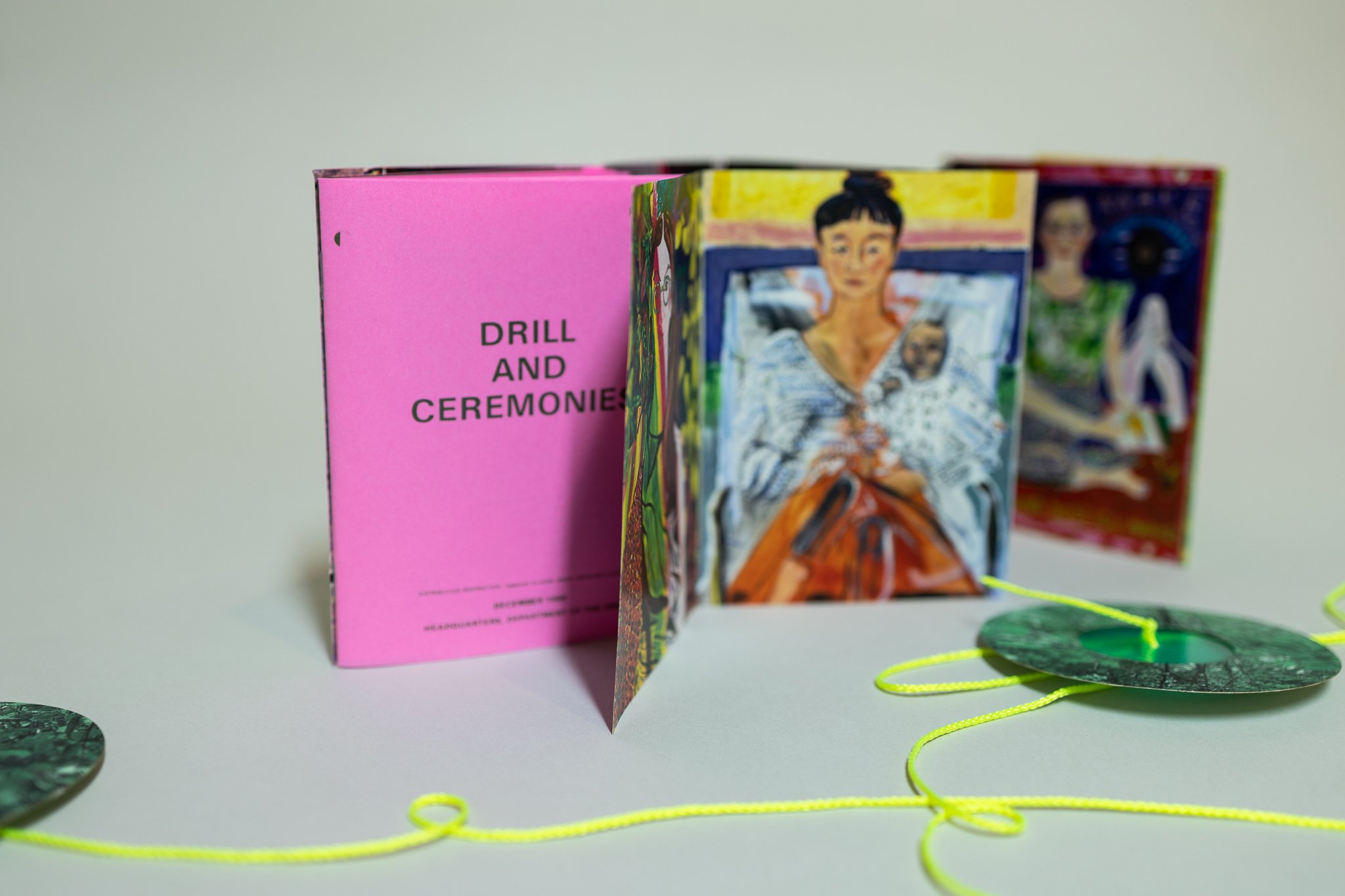

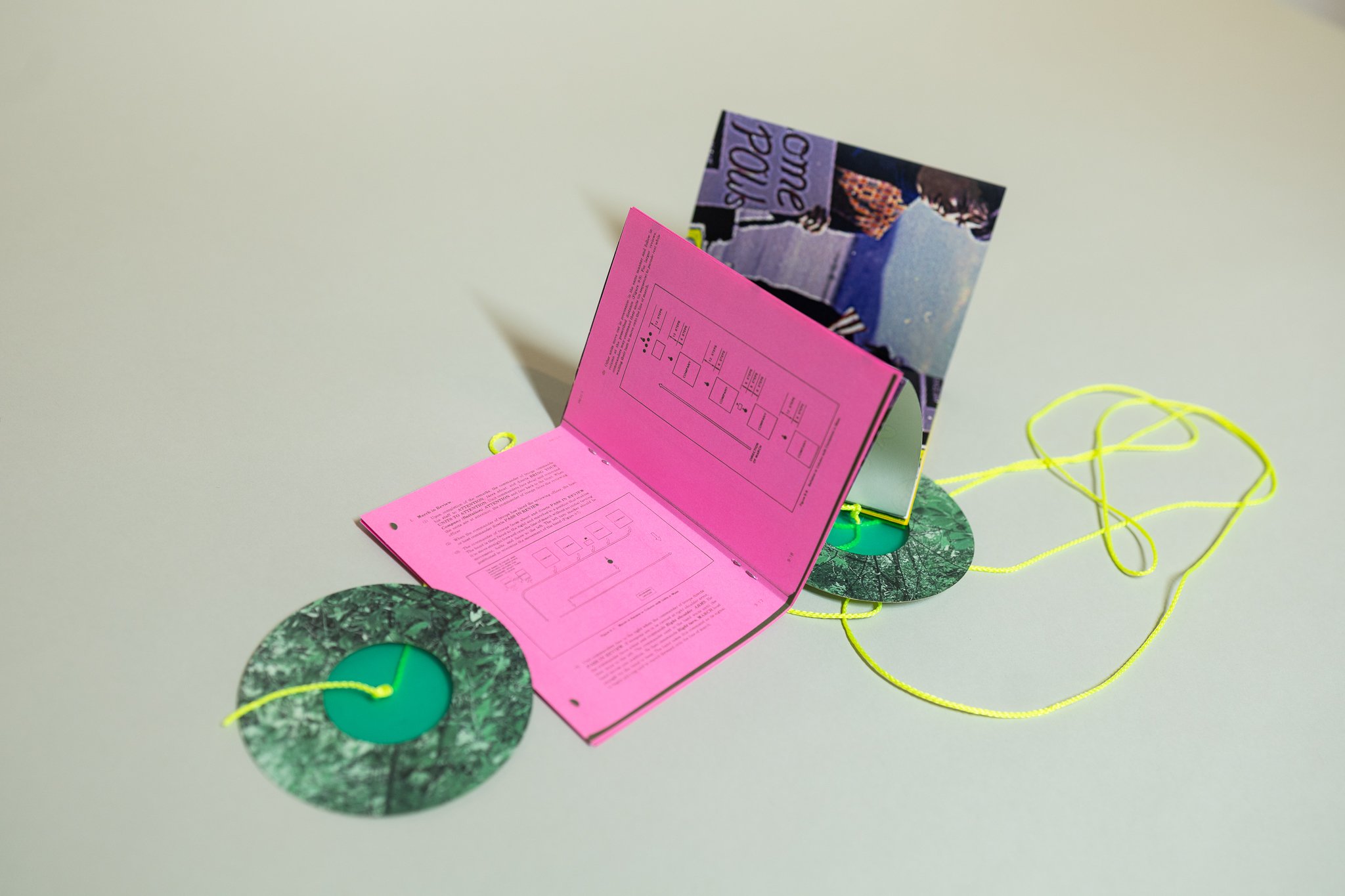

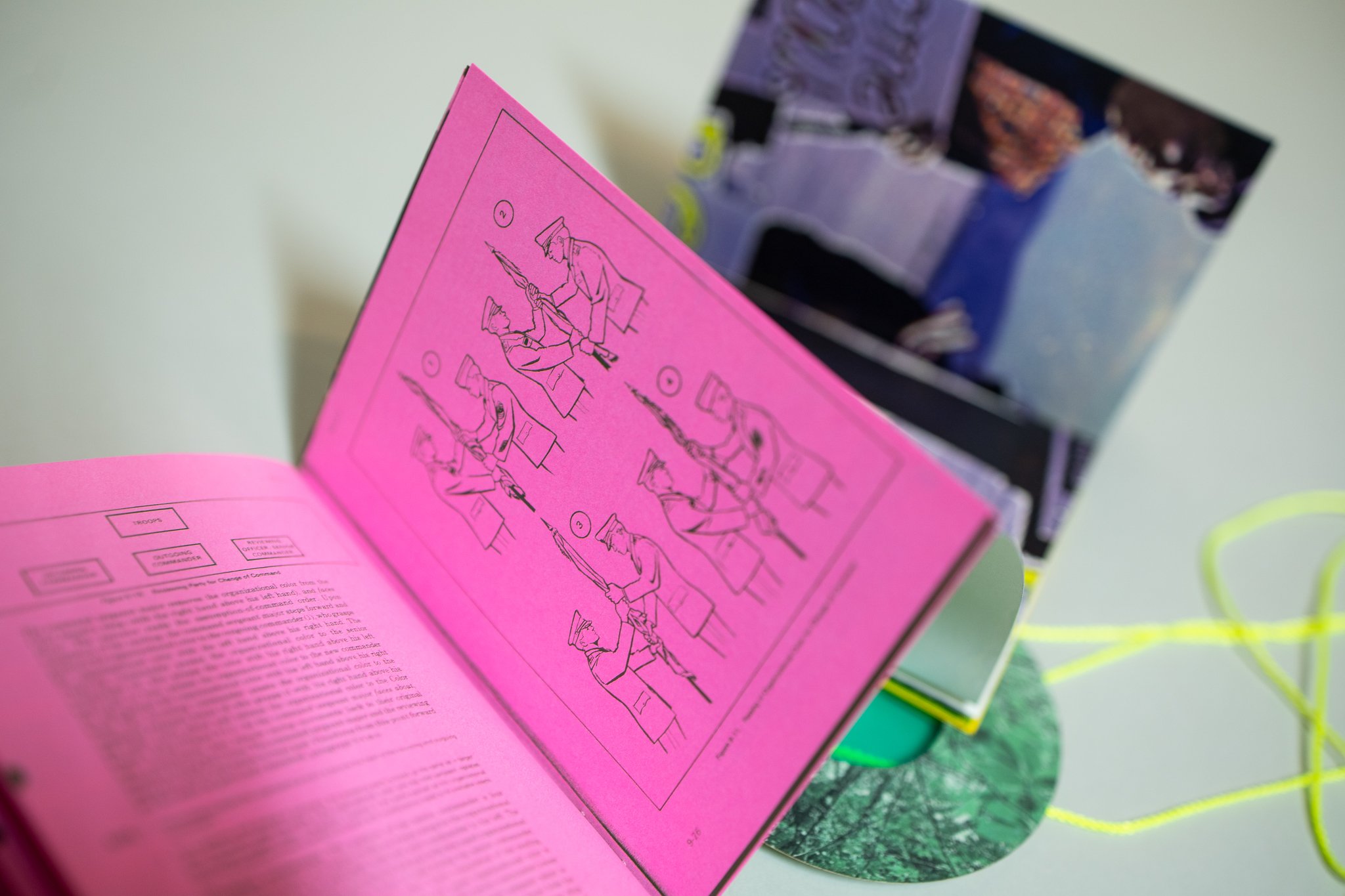

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 23, Spring 2022, Shower of Comets, reflects on the spaces between ordinary life and war. This zine is about no war in particular, but aims to explore how war can be abstract and obscure. The whole book is tied together with a paper teletone that was modeled off of a 1950s vintage science toy. Like a paper cup, you can speak into one paper disc, and someone can hear you from the other disc if they put it up to their ear. Alluding to children’s pretend war games, the disc features foliage from the Ke Bang National Park in Vietnam, where crucial battles took place during the Vietnam War. The center of the disc is made of green film as a reference to night vision or the sight of a gun.

Once you have unwrapped the teletone, the first pamphlet is an excerpt from an old military manual, Drill and Ceremonies, from the chapter “Reviews.” This chapter details the ceremonial practices and procedures meant to honor and salute distinguished individuals, alongside diagrams that show how such a performance would take place. I was moved by the thoughtfulness of the traditions, but remain mindful of how these gestures make the subject of war impalpable.

This pamphlet leads to the beautiful poetry of Charlie Samuya Veric from his book Boyhood, a lyrical reconstruction of his childhood hometown Ibajay, Aklan, on the island of Panay in central Philippines. During his youth, there were communist insurgencies where armed members of the revolutionary movement resisted the Cory Aquino regime. In Veric’s work, he refers to green trucks, which were the military vehicles that these insurgents used. From his vantage point, the images of brutality are difficult to understand, as if the stains of violence are more like a “shower of comets,” from which this quarterly takes its name.

Alongside Veric’s poetry are four portraits by Heidi Howard, who makes portraits from seated individuals in her studio and other places. Howard’s lively portraits are done in real time over the course of many hours. They are sensitive and express a kind of friendship between Howard and the subject. I wanted to place these portraits in the context of war, because it is exactly Howard’s type of ordinary that I know to be a constant in times of both war and peace. Yet, it is hard for me to fill the theater of war with portraits of people who are sitting in composure.

Sandwiched between Veric’s and Howard’s work is an image of the wives of US Marine POWs who were released from Hanoi in 1973. Their welcome signs, which use similar colors to the Howard paintings, read “Welcome Home POW” and “God Bless You All.” Since the end of March, many Ukrainians have fled their homes. This morning, as I was scrolling through the Financial Times, I saw an image of a young couple walking through a bloom-filled National Botanic Garden in Kyiv on April 28, 2022. Even when there are few people to wander the gardens, spring will still yield green.

– Tammy Nguyen, Editor-in-Chief

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 23, Spring 2022, Shower of Comets was created using xerox on various papers and laser cut lighting gels. It was designed and edited by Tammy Nguyen. It was produced by Téa Chai Beer and Holly Greene with assistance from Clara Burger, Hunter Julo, Spencer Klink, Mely Kornfeld, Maia Panlilio, Robbie Scola and Olivia Thanadabout. It was an edition of 200.

Martha's Quarterly

Issue 22

Winter 2022

Make Me A World

8.5” x 6.5”

About the contributors:

Herbert Hoover was the 31st president of the United States.

Nawin Nuthong is an artist who lives and works in Bangkok, Thailand. He always marks the junction between simulation and history to speculate on art practice.

On March 18, 2014, a few days before the end of Winter, Vladimir Putin stood before the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation in St. George Hall of the Grand Kremlin Palace and made his case on the incorporation of Crimea into Russia. Floating above a suited assembly were giant gold chandeliers that beamed light off of curved and immaculate white walls, reflecting this pivotal moment in modern Russian history. As fireworks lit the night sky outside for the public, Putin proclaimed Crimea’s inherent place within Russia’s domain:

Everything in Crimea speaks of our shared history and pride. This is the location of ancient Khersones, where Prince Vladimir was baptized. His spiritual feat of adopting Orthodoxy predetermined the overall basis of the culture, civilisation and human values that unite the peoples of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The graves of Russian soldiers whose bravery brought Crimea into the Russian empire are also in Crimea.

This is also Sevastopol – a legendary city with an outstanding history, a fortress that serves as the birthplace of Russia's Black Sea Fleet. Crimea is Balaklava and Kerch, Malakhov Kurgan and Sapun Ridge. Each one of these places is dear to our hearts, symbolizing Russian military glory and outstanding valor. (1)

To Putin, Crimea was always part of Russia’s world.

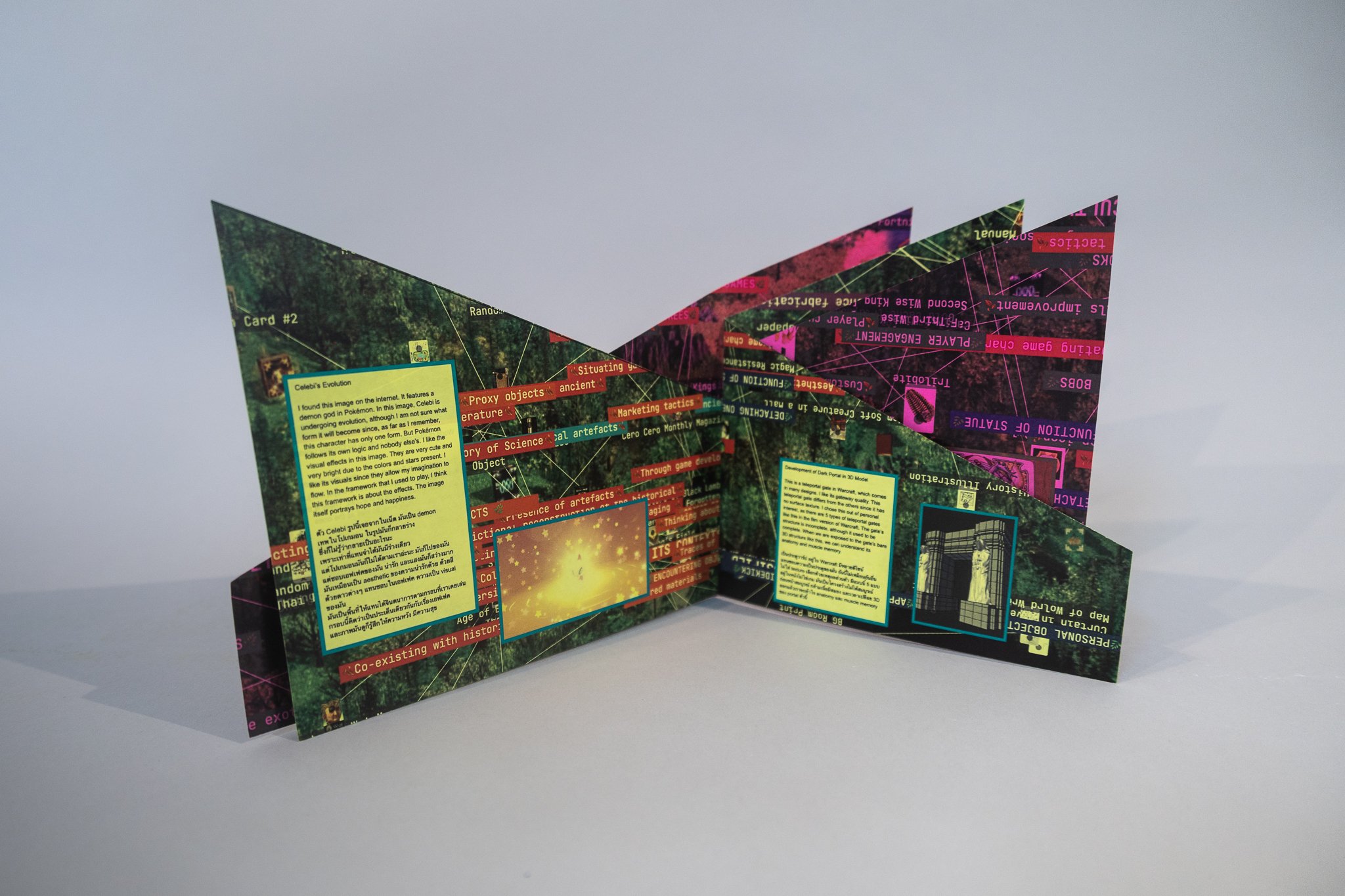

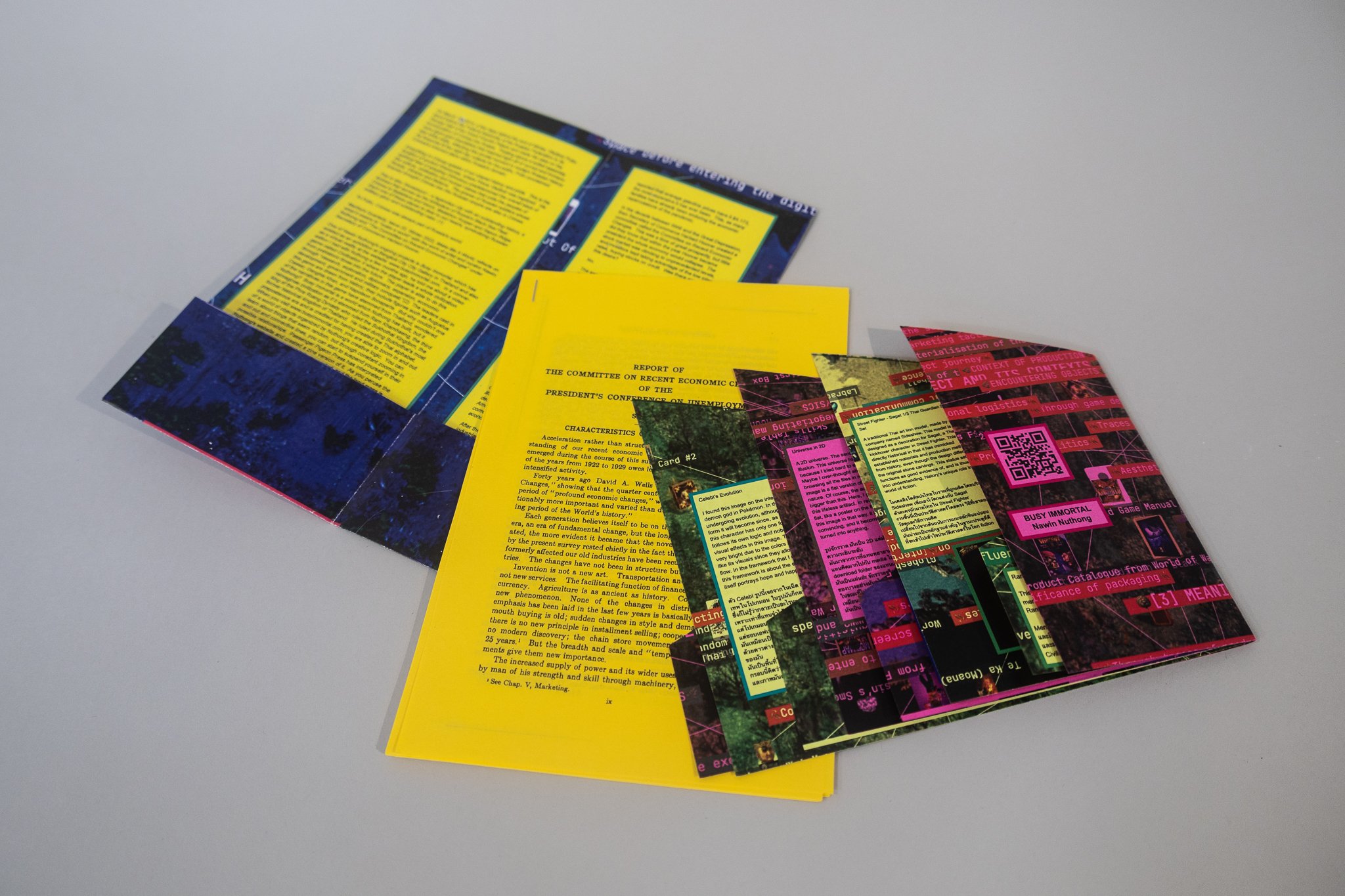

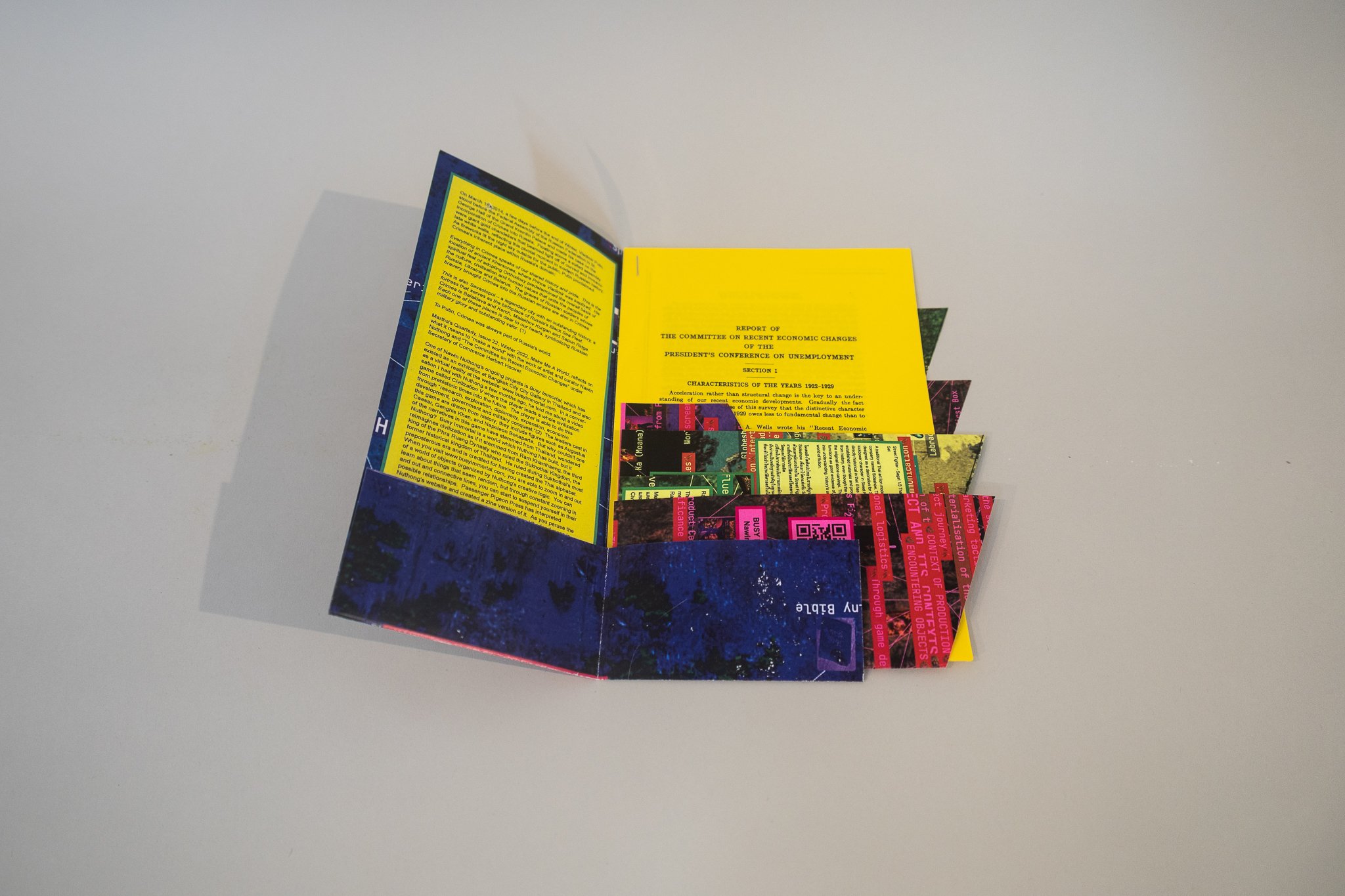

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 22, Winter 2022, Make Me A World, reflects on what it means to “make a world” with the work of artist and curator Nawin Nuthong and “The Committee on Recent Economic Changes” under Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover.

One of Nawin Nuthong’s ongoing projects is Busy Immortal, which has existed as an exhibition at Bangkok City City Gallery in Thailand and also as a virtual reality at the website: www.busyimmortal.com. In a conversation I had with Nuthong a few months ago, he told me about a video game called Civilization V where the player leads a whole civilization from prehistoric times into the future. The player is able to do this through “research, exploration, diplomacy, expansion, economic development, government and military conquest.”(2) The leaders cast in this game are drawn from history; they include figures such as Augustus Caesar, Genghis Khan, and Napoleon Bonaparte. But why couldn’t one of the narratives in this game have stemmed from Thailand, wondered Nuthong? Busy Immortal is a world which Nuthong has built, but it reimagines civilization as if it stemmed from Ram Khamhaeng, the third king of the Phra Ruang Dynasty who ruled the Sukhothai Kingdom, the former historical kingdom of Thailand. He ruled during Sukhothai’s most preposterous era and is credited for having created the Thai alphabet. When you visit www.busyimmortal.com, you are able to zoom in and out of a world of objects organized by Nuthong’s creative logic. You can learn about things that seem random, but through constant zooming in and out and connective lines, you can start to suspend yourself in their possible relationships. Passenger Pigeon Press has interpreted Nuthong’s website and created a zine version of it. As you peruse the pages, a mountainous landscape is suggested, and the land mass is filled with screen captures and selections from Busy Immortal. You can also use the QR code to visit the original site.

Our whole world awoke to the news that Russia had invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022. For Ukrainians, their world had been punctured by a larger power whose leader had a different vision of how their world should be defined and contained. After the first day of war, the 44-year-old comedian-turned-president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, addressed his nation:

Today, I asked the twenty-seven leaders of Europe whether Ukraine will be in NATO. I asked directly. Everyone is afraid. They do not answer.

And we are not afraid of anything. We are not afraid to defend our state. We are not afraid of Russia. We are not afraid to talk to Russia. We are not afraid to say everything about security guarantees for our state. We are not afraid to talk about neutral status. We are not in NATO now. But the main thing – what security guarantees will we have? And what specific countries will give them? (3)

Translators around the world could be heard tearing up as they translated President Zlenskyy’s address into other languages. The people of Ukraine now must endure this war. Many will die; many are refugees; thousands of personal worlds are shattered.

In a world far away, many Americans were abhorred by the Russian invasion. Protests for Ukraine’s sovereignty sprouted all over commons across America. As this happened, many Americans also wondered how this war could have a direct impact on their own lives. Oil, oil, oil, said all the talking heads on the right, left, and in between. As I write this introduction, it is March 8th, 2022 and the Wall Street Journal has reported that average gasoline prices have it $4.173, the most expensive it has ever been. This, as many families have already been enduring the economic repercussions of the pandemic.

In the decade between WWI and the Great Depression, then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover created a committee called the Committee on Recent Economic Changes. This was a time of great prosperity, but little did they know that within the year Hoover became president the whole economy would collapse. The stock market was climbing to unprecedented levels, and investors kept taking advantage of the low interest rates, buying stocks on credit. Was there any limit to this desire?

No.

The second component of this Martha’s Quarterly is a report that the Committee on Recent Economic Change published just before The Great Crash. The report summarizes American spending in between the years 1921-1928. It details how technology, geography, wages, and the cost of living all work harmoniously to create an environment wherein the public can satiate their desires, or in other words, build and fill their worlds:

Perhaps the deepest economic significance of the new situation lies, not in the rapidity with which the service industries have grown and have become integrated, nor in the universality of their spread, but in the fact that the situation which they have created is reciprocal. Our increasing standard of living is not participated in only by those who produce our food, clothing, and shelter, but has flowed back to those in the service industries. The population as a whole can enjoy the rising standard of living–the music which comes in over the radio, the press, the automobile and good roads, the schools, the colleges, parks, playgrounds, and the myriad other facilities for comfortable existence and cultural development.

Our ancestors came to these shores with few tools and little organization to fight nature for a livelihood. Their descendants have developed a new and peculiarly American type of civilization in which services have come to rank with other forms of production as a major economic factor.

After the stock market crashed in the Fall of 1929, industrial production quickly plummeted and economic suffering pervaded society leading to hunger and death. It goes without saying that human civilization is all interconnected; but, we can also consider that the collapse of one world does not birth a new one, but rather destroys the worlds around it.

– Tammy Nguyen

Martha’s Quarterly, Issue 22, Winter 22, Make Me A World, was edited and produced by Passenger Pigeon Press. Tammy Nguyen directed the content and design. Nawin Nuthong’s contribution was edited by Spencer Klink. The introduction was edited by Téa Chai Beer. This edition was produced by Holly Greene and Maia Panlilio. The artist book was created using xerox on colored and glossy white text weight papers. Arial font was used throughout in various sizes and styles. This was an edition of 200.